The

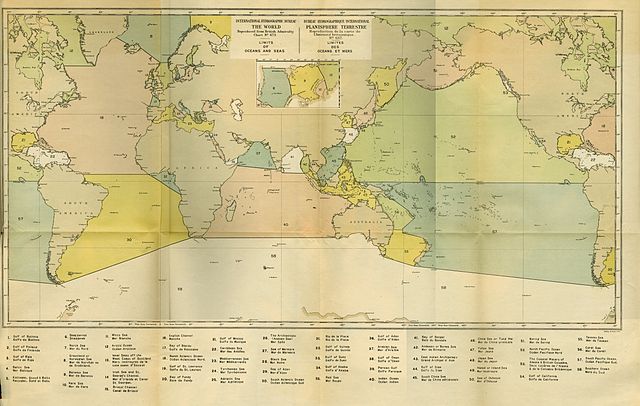

Publication S-23 "Limits of Oceans and Seas" was published by the IHB

in 1929 to define names and limits of seas and to be used for safe

navigation, hydrography and oceanography.

S-23 was based on the Resolution adopted in the first International Hydrographic Conference in London in 1919, which mentioned that names and limits of seas and oceans should be defined for safe navigation.

S-23 was based on the Resolution adopted in the first International Hydrographic Conference in London in 1919, which mentioned that names and limits of seas and oceans should be defined for safe navigation.

S-23 1st edition, 1928 :

The very end of the legend is the "Southern Ocean" (mers du Sud).

The very end of the legend is the "Southern Ocean" (mers du Sud).

From Economic Times by Vikram Doctor

In May 1988, the Times of India (ToI) reported on an issue riling readers of Pakistan Times, a now defunct newspaper that was then owned by the Pakistani government.

This was the name of the Indian Ocean which they felt was unfairly linked to this country simply because “by calling itself India the country seemed to have become heir to the entire history of the subcontinent.”

One writer felt that the fairer approach would be to limit the use of India up to August 1947 and after that “what remained outside Pakistan and Bangladesh should be called Bharat.”

But since the Indian government had not been so obliging, writers felt Pakistan should not go along with this historical and geographic appropriation and should stop using the term “Indian Ocean’.

One writer proposed calling it the Indo-Pak Ocean as a fair solution.

A more diplomatic correspondent felt this would annoy other countries in the region, but suggested that, because many of these countries were Islamic, the Muslim Ocean was the right term.

“All Muslim countries should agree to such a proposition and the matter should be taken up at the Organisation of Islamic Conference,” he says.”

Chart of the Indian and Part of the Pacific Oceans, 1870

Pakistan’s irritation with the Indian Ocean name goes back even further.

In March 1971, ToI reported on a presentation made by Latif Ahmed Sherwani of the Pakistani Institution of International Affairs at a seminar in Georgetown University, Washington DC, on Indian Ocean affairs.

Sherwani pointed out that the Mediterranean wasn’t known as the Italian Sea, despite Italy occupying a prominent position in it, just as India did in the Indian Ocean.

So in the same way a name should be used that was more respectful of the many countries around the Indian Ocean’s rim.

He suggested calling it “the eastern ocean or the Afro-Asian ocean.”

courtesy of CPGS

Even further back though, an objection to ‘Indian Ocean’ came not from Pakistan, but Indonesia.

In July, 1963 ToI reported the startling news that Indonesia's President Sukarno wanted Indonesia's Navy to call the Indian Ocean as the Indonesian Ocean and his Chief of Staff of the Navy Eddy Martadinata had issued an order making the change.

Martadinata later became ambassador to Pakistan where he may have enjoyed meeting others peeved about the persistence of ‘Indian Ocean.’

China’s position

Matters of sea are important to Indonesia which is a nation of islands.

This includes the Natuna Islands, an archipelago of 272 small islands that lie in a part of the sea where they rub up against China.

That whole area is generally known as the South China Sea but last week the Indonesian government said that the part near their islands would now be called the North Natuna Sea.

Natuna islands with the GeoGarage platform (NGA chart)

China’s response was predictable.

“Some countries so-called renaming is meaningless,” said a Chinese foreign ministry spokesman.

Some idea of Chinese views about the region can be seen in a statement made at an international conference in 2015 by Chinese Vice Admiral Yuan Yubai, who stated bluntly, “the South China Sea, as the name indicates, is a sea area that belongs to China.”

The Chinese government’s position on the sea is inherited from its predecessor, the Republic of China (RoC).

In the aftermath of World War II the RoC released the Nine-Dash line, a map with nine dashes encompassing nearly all of the sea between the Chinese mainland and the countries of South-East Asia, all claimed for China.

After the RoC collapsed and moved to Taiwan, its communist successor continued to maintain the claim (though the RoC in Taiwan has never officially dropped it either).

According

to the Resolution, the name "Sea of Japan" was registered in 1923 and

was adopted in 1929. After the publication of S-23, cartographers all

over the world have been referring to the publication when they produce

maps and charts.

Since the 1st edition of S-23, the name "Sea of Japan" has been used until the 3rd edition was published in 1953 when the Republic of Korea was not a Member State of the IHO.

Since the 1st edition of S-23, the name "Sea of Japan" has been used until the 3rd edition was published in 1953 when the Republic of Korea was not a Member State of the IHO.

After

the long usage of S-23, it was decided at the 11th International

Hydrographic Conference in 1977 that a new edition of S-23 should be

produced, and the IHB made a draft 4th edition and circulated the draft

to all Member States in 1986.

However, it was not adopted.

After a long preparation of a new edition of S-23, the IHB circulated a new draft 4th edition of S-23 in August 2002.

After a long preparation of a new edition of S-23, the IHB circulated a new draft 4th edition of S-23 in August 2002.

There

were various changes - for instance, the name of the publication was

changed from "Limits of Oceans and Seas" to "Names and Limits of Oceans

and Seas", and 60 seas were given new names. However, the publication

did not include the name of the sea area between Korea and Japan and

left it blank.

The IHB suddenly withdrew the draft 40 days after the circulation due to various problems.

The IHB suddenly withdrew the draft 40 days after the circulation due to various problems.

Wide Gulf

An even more intensely felt maritime dispute in the region has been running for decades over the name for the sea between Korea and Japan.

The general convention is to call this the Sea of Japan, but South and North Korea affirm passionately that they always called this the East Sea and that its appropriation by Japan continues the humiliating colonisation of Korea by Japan and atrocities committed during WWII.

The Koreas have pleaded in multiple international meetings for at least parity, with both names being recognised, but Japan remains stonily unresponsive, inflaming the matter even more.

Another dispute over maritime naming, in a particularly volatile region, is over the Persian Gulf.

The ancient Greeks referred to this as the Sinus Persicus, with Sinus Arabicus (Arabian Gulf) sometimes used for what became more commonly known as the Red Sea.

The six Arab countries who border the Persian Gulf strongly feel that their control of around 70% of the coastline gives them the right to rename it the Arabian Gulf now.

Sinus Persicus Qatif map, 1658

Iran refuses to countenance this even though, ironically, it has moved away from the term Persia in most other ways.

The term Iran, which derives from Aryan, applies for most of the country, except in matter concerning the Gulf.

There is an official National Persian Gulf Day on April 30th, the top Iranian soccer teams play in the Persian Gulf Pro League and airlines found to be using any term other than Persian Gulf on their in-flight information systems are banned from flying in Iranian air-space.

According to a paper by Martin Levinson, following the Islamic Revolution of 1979 there were moves to promote the term Islamic Gulf – which presumably the Pakistani proponents of the Muslim Ocean would have appreciated.

This idea disappeared after the start of the inter-Islamic Iran-Iraq war, but apparently was revived by Osama bin-Laden and used as a term to rally Islamic militants.

Limits of Oceans and Seas (1953) : sheet 3 Indonesia

Building blocks

This underlines the larger dangers of maritime naming disputes.

Land based naming disputes are numerous, but they tend to settled by the brute principle of physical possession.

Laying claim to the open sea is harder and it is partly why opponents try and enlist more solid features like continental shelves, shoals and reefs as a way to buttress their position (China has been accused of actually building islands for this purpose).

The real problems come with the economic benefits which, inconveniently tend to be less easy to pin down.

Sea lanes for ships tend to be in the most open waters, submarine oil and gas fields stretch in unpredictable directions and shoals of fish which, as they dwindle through overfishing are increasingly desperately sought after by national fishing fleets, and are the hardest of all to demarcate in national areas.

From IHO 23-3rd: Limits of Oceans and Seas, Special Publication 23, 3rd Edition 1953,

published by the International Hydrographic Organization.

Accidental ownership

In all this India is something of an exception.

Our name attaches to one of the largest maritime expanses of all, but the country has never seemed too concerned about defending this.

Periodically our politicians boast about the blue-water ambitions of the Indian Navy and the potential of Indian Ocean commerce, but they then go back to land based issues.

Coastal issues are literally marginal in India, with fishing communities struggling to receive the same attention paid to farming ones.

This might reflect the fact that our ownership of the Ocean name is somewhat accidental.

As with most things involving the predominantly Western developed system of cartography, it was first used by the Greeks tracking the sources of the prized spices and textiles from India.

As Martin W.Lewis explains in his essay ‘Dividing the Ocean Sea’ (1999), the Greeks began the somewhat arbitrary division between sea (thalassa) which meant the Mediterranean for them, and the wider Oceanos, the world of sea that lay at the edge of the world of land.

Travel and trade made them refine this view and from fairly early on the term Indikon pelagos was used for the seas around India.

The Roman geographers who built on their knowledge occasionally made a distinction between the waters closer to India and the open sea they knew existed beyond Ceylon, which they called Mare Prosodum or the Green Sea.

Other terms were used like Oceanus Orientalis, Ethiopian Ocean (for the parts closer to Africa) and Mare Barbaricum, but probably following the traders who actually sailed the seas, they always came back to Indian Ocean.

An unusual and attractive 1658 map of the Indian Ocean, or Erythraean Sea, as it was in antiquity. Composed by Jan Jansson after a similar 1597 map published by A. Ortelius in his Parergon .

Covers from Egypt and the Nile valley eastward past Arabia and India, to Southeast Asia and Java. Cartographically, India, Arabia, and Africa roughly correspond to the conventions of the period. Southeast Asia is less recognizable, but the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, and Java are clearly noted.

Most of the place names used throughout are derived from Ptolemy, who himself based his description of the region heavily on records from Alexander the Great's conquests.

Two smaller maps in the upper left and right quadrants are of exceptional interest.

The upper left chart shows northwestern Africa and is titled Annonis Periplus.

This is a reference to the legendary expeditions of the Carthaginian King Hanno, said to have been the first to access the Indian Ocean by sailing around the southern tip of Africa.

Incidentally, en route, he is also said to have been the first to tame a lion.

The upper right chart shows the northern polar regions as they were perceived at the time.

A landmass covering the polar ice cap is indentified as Hyperborea.

To the left of this, roughly where North America rests today, the island of Atlantis appears; while Scythia, Europe (Thule) and Asia are on the right. Greenland and possibly Iceland appear at the bottom.

This map is intended to point out the possibility of a Northeast Passage to Asia, which was at the time being actively sought after by Dutch, English, and Russian navigators.

Both smaller maps, the primary title area at top center, and an Latin explanation for the map at bottom center, are surrounded by baroque strapwork style borders.

This remarkable map was published in volume six, the Orbis Antiquus , of Jan Jansson's Novus Atlas .

Bharatiya Ocean ? This persisted through the 16th century as increasing knowledge from the global voyages of explorers like Magellan lead to the creation of the first atlases.

The Atlantic has received its name from the Greeks, who saw it as the edge of the world, held up by the giant Atlas, but then explorers broke through to the Pacific, after sailing down south and surviving the storms of Cape Horn at the tip of South America, to come to the more peaceful seas to its north.

Explorers going north and south added the Arctic and Antarctic Oceans, although geographers have argued about whether these count or not.

Different divisions have given the seven oceans that, in number at least, correspond to the seven seas of ancient Arabic and Indian legend, or four oceans, or even just one – as one geographer pointed out, if you invert the globe and look from the South Pole there is just one vast sea with three great bays that are the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans.

Even in this the Indian connection remains, and oddly the only threat to it might come from ultra-nationalists who believe in elevating the term Bharat over India.

They argue that this internal name should be the external one too, ignoring the long global history of the use of India.

They might want to consider how imposing this change would delight maritime minded Pakistanis since the chances of getting the world to accept the idea of a Bharatiya Ocean accepted are nil.

Links :

- Wikipedia : Borders of the oceans

- 'Limits of Oceans and Seas' : S-53 revision, 4th revided edition 1986, 4th draft edition 2002

- KoreaHerald : Change of meaning in ‘East Sea’ and ‘Sea of Japan’

- State.gov : Coastal states'maritime claims

- GeoGarage blog : Japan offers archival evidence in island territorial disputes / Conflict and diplomacy on the high seas / How the U.S. maps the World's most disputed territories / Troubled waters: the South China Sea dispute

.jpg)

_in_Antiquity_-_Geographicus_-_ErythraeanSea-jansson-1658.jpg/800px-1658_Jansson_Map_of_the_Indian_Ocean_(Erythrean_Sea)_in_Antiquity_-_Geographicus_-_ErythraeanSea-jansson-1658.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment