The genius math behind ship anchoring

— Science girl (@sciencegirl) January 30, 2026

pic.twitter.com/1gGXqZm5dd

GeoGarage blog

Daily press & media panorama with maritime thematic

Saturday, January 31, 2026

The genius math behind ship anchoring

Friday, January 30, 2026

It’s hard to fathom how large supertrawlers’ nets are – Equivalent to 3 Eiffel towers lying down

In OCEAN With David Attenborough, cameras captured what it looks like on

the seabed when a supertrawler's enormous net is unleashed.

Image credit: OCEAN With David Attenborough

From IFL Science by Rachael Funnell

Fishing has been a vital source of protein and nutrients for humankind for millennia, but as the years have gone by, we’ve gotten a little bit too good at it.

Ships now operate at sea trailing nets behind them at sizes that would blow the mind of the earliest fishers.

To be honest, their enormity is even hard to comprehend in the modern era.

Supertrawlers are massive industrial fishing ships that themselves are pretty huge.

Supertrawlers are massive industrial fishing ships that themselves are pretty huge.

They can be over 100 meters (328 feet) long, but that’s child’s play compared to what’s happening under the surface.

According to the Sussex Dolphin Project, the fishing net of a supertrawler can be 10 times the length of the ship itself at around a kilometer (0.6 miles) long.

According to the Sussex Dolphin Project, the fishing net of a supertrawler can be 10 times the length of the ship itself at around a kilometer (0.6 miles) long.

If you’re struggling to get your head around that, it’s roughly the equivalent of 14 jumbo jet planes, or three Eiffel Towers laying down.

In the case of bottom trawlers, this method of fishing entails dragging a chain or metal beam along the seafloor.

In the case of bottom trawlers, this method of fishing entails dragging a chain or metal beam along the seafloor.

It forces anything it disturbs into the net behind and destroys coral communities that can take decades to recover, adversely affecting biodiversity.

The visceral, heart-wrenching footage featured in the clip is the first time the process of bottom trawling was filmed in such high quality and the immense scale of trawling’s destruction revealed.

This destructive fishing method occurs daily across the globe; as Attenborough says in the clip, “very few places are safe from this.”

Iron chains bulldoze across the seabed, leaving trails of devastation in their wake that are visible from space.

Attenborough reveals that trawlers, often on the hunt for a single species, discard almost everything else, remarking, “it’s hard to imagine a more wasteful way to catch fish.”

An area almost the size of the Amazon rainforest is trawled every year, with the same places being trawled repeatedly, without the chance to recover.

Only by revealing this footage to the world and exposing what’s happening beneath the surface can people start to truly understand the impact on marine life.

“I've been working on marine conservation science for over 35 years, and we did the research that showed that bottom trawling, by churning the sediment on the sea floor, produces carbon dioxide emissions that are on the scale of global aviation every year,” marine ecologist Enric Sala, Executive Producer and Scientific Advisor on OCEAN, and National Geographic Explorer, told IFLScience.

“I have seen the bycatch on the deck of trawlers, but like everybody else, I had never seen what the trawl does underwater.”

“We had all this info, all this data that hits the brain, but this hit me in the guts. Being at the level of the net and seeing all these poor creatures trying to escape the net, that's something that nobody else had seen. What the film does so powerfully is that now people can see for themselves, right? It's not about believing one side or another. People can see for themselves, and they can make up their minds about this practice.”

These protected areas dispel the myth that we cannot protect more of the ocean because that would harm the fishing industry.

“We had all this info, all this data that hits the brain, but this hit me in the guts. Being at the level of the net and seeing all these poor creatures trying to escape the net, that's something that nobody else had seen. What the film does so powerfully is that now people can see for themselves, right? It's not about believing one side or another. People can see for themselves, and they can make up their minds about this practice.”

These protected areas dispel the myth that we cannot protect more of the ocean because that would harm the fishing industry.

Dutch-owned trawler FV Margiris, the world's second-biggest fishing vessel, shed more than 100,000 dead fish into the Atlantic Ocean off France, forming a floating carpet of carcasses that was spotted by environmental campaigners.

The spill, which happened in 2022, was caused by a rupture in the trawler's net, said fishing industry group PFA, which represents the vessel's owner.

In a statement, the group called the spill a "very rare occurrence."

The French arm of campaign group Sea Shepherd first published images of the spill, showing the ocean's surface covered by a dense, layer of blue whiting, a sub-species of cod, which is used by the industry to mass-produce fish fingers, fish oil and meal.

Sea Shepherd France said it doubted the incident was an accident.

Lamya Essemlali, head of the campaign group in France told Reuters her NGO was inclined to believe the fish were deliberately discharged.

"The EU regulation has been implemented so that we can reduce the non-selective fishing methods because it's very demanding, time-consuming and costs money for a fishing vessel to go back to port and unload the bycatch, and then go back at sea," she explained.

This bycatch can include numerous animals that aren’t the target species, ranging from small animals to creatures like turtles, sharks, and dolphins.

With fishing windows stretching for hours at a time, surviving long enough to be released isn’t a guarantee.

Trawling practices have adapted in recent years to try and address the issues of bycatch and sustainability.

These include cameras that can alert skippers when the wrong animals get trapped in the nets and enable them to pull the nets back up when the target species isn’t there.

A new approach also uses “flying doors” that are dragged just above the seabed, instead of across it.Concerns remain, however, as traditional trawling continues to be rife in areas of the ocean that are meant to be Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).

In the UK, Greenpeace reported that 26 supertrawlers collectively spent 36,918 hours fishing in 44 MPAs between 2020 and early 2025 – but under the current government legislation it’s legal to do so, as bottom trawling is permitted in 90 percent of UK MPAs.

Such practices have a knock-on effect for the environment, but also for fishers.

Such practices have a knock-on effect for the environment, but also for fishers.

The negative impact on biodiversity means there’s fewer fish to catch, and trawling itself replaces more selective methods of fishing that generate more jobs and have a lower environmental impact.

The worst enemy of fishing is overfishing, not protected areas.

Enric Sala

Enric Sala

The good news is that the ocean has made a strong case for its ability to bounce back.

Just look at Papahānaumokuākea, one of the largest marine conservation areas in the world the proved large-scale marine protected areas for migratory species can work.

The marine conservation area gave yellowfin tuna a safe place to reproduce, and as they spread, we saw a boost in yellowfin tuna in surrounding areas of 54 percent.

It really is as simple as more fish means more fish, for everyone – including fishers.

“These protected areas dispel the myth that we cannot protect more of the ocean because that would harm the fishing industry,” said Sala.

“These protected areas dispel the myth that we cannot protect more of the ocean because that would harm the fishing industry,” said Sala.

“The worst enemy of fishing is overfishing, not protected areas. Protected areas are key to the future, and the industry. These areas are key to replenish the rest of the ocean and ensure that we have fish to catch and eat into the future.”

Links :

- GeoGarage blog : Trawler 14 times the size of UK fishing boats is plundering ... / Supertrawlers 'making a mockery' of UK's protected seas / Fishing industry still 'bulldozing' seabed in 90% of UK marine ... / Tackling illegal fishing in western Africa could create ... / Huge bank of dead fish spotted off French Atlantic coast

Thursday, January 29, 2026

Florentino Das: a shoestring voyage of adventure across the Pacific in a 24ft boat

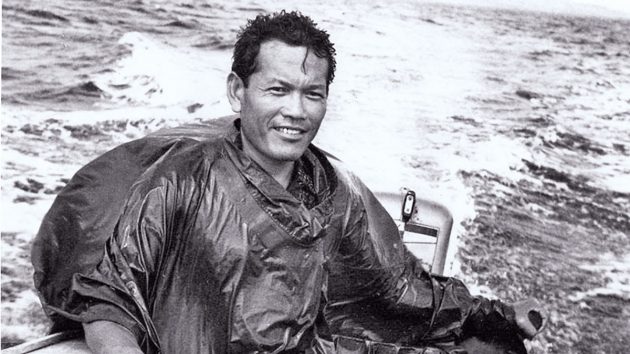

Florentino Das’s 4,700-mile Pacific voyage on Lady Timarau took him 346 days.

Credit: Collection of Pio Arce Credit: Collection of Pio Arce

From PBO by Richard King and Serafin Colmenares Jr.

Escaping the recent horrors of World War II, thousands of veterans and civilians in the 1950s sought respite and freedom out at sea in small boats, write Richard King and Serafin Colmenares Jr.

They include a stream of now famous single-handers such as Edward Allcard, Ann Davison, and Sir Francis Chichester.

Over in the Pacific Ocean, a solo voyage by a DIY fisherman-carpenter-mechanic was no less extraordinary, yet it is now barely remembered in sailing histories.

This man’s reasons were less about post-war escape and more about returning home and earning pride for his family and community.

Born in 1918, Florentino Resulta Das grew up on the island of Samar in the Philippines, the son of a man who ran a 60ft ferry.

Model of Florentino Das’s Lady Timarau at the Filipino Community Center, Honolulu, Hawaiʻi.

Credit: Serafin P. Colmenares, Jr

Florentino Das grew up learning from his father, helping him build boats, and marvelling at his ability to predict landfalls based on the wind and stars.

At 16, Das stowed away on an English freighter to Hawaiʻi. In the middle of the Great Depression, he found work where he could, including as a boxer.

He married Gloria Lorita Espartino; together they raised eight children.

Florentino Das worked as a fishing boat captain, carpenter, ceramicist, and at the Pearl Harbour shipyard. He repaired boats and cars.

After some 20 years in Hawaiʻi, Das decided to return home.

He couldn’t afford a passage by ship or plane, so resolved to take a small boat with the hopes of, once home, establishing a fishing or ferry business to fund plane tickets for his family.

Florentino Das on departure day. Crowds saw him off and priests blessed his voyage.

Credit: Collection of Pio Arce

With the help of his children over three years in his backyard, Florentino Das built Lady Timarau using a Navy surplus hull.

He replaced structural parts with spare timbers, added a mast and a centreboard, and scavenged parts of other vessels to construct a 24ft wooden boat with four watertight compartments.

It had a self-draining cockpit and was built so he could dog himself into the cabin in any weather.

Das set up the sloop with two 25hp outboard engines.

His project generated some sponsorship from the Timarau Club of Honolulu.

Florentino Das departed from Kewalo Basin in Honolulu on 14 May, 1955.

Only a couple of hours out of the harbour, his main boom broke.

His project generated some sponsorship from the Timarau Club of Honolulu.

Florentino Das departed from Kewalo Basin in Honolulu on 14 May, 1955.

Only a couple of hours out of the harbour, his main boom broke.

He replaced this with an oar.

Das’s voyage made headlines in Hawaiʻi and his voyage was followed by the press.

Credit: The Honolulu Advertiser, April 26, 1956

As Das caught up on sleep, he realised he’d forgotten some key parts for his outboards, a mirror, ‘sunburn oil’, a sea anchor, a regular anchor, nets for fishing, and spare batteries for his radio.

Then in early rough weather, he was, as he wrote, “shaken like a dice in a cup.”

Yet soon Das began to settle in.

He had a sextant, a compass, two wrist watches, and he knew the stars well.

He had a mainsail with a short gaff, a staysail, and a spinnaker of parachute material.

He used a small stove to make coffee and to warm food, and he’d loaded 35gal of water, four gallons of wine, four quarts of whisky, and 150gal of gasoline, stowing this intentionally for stability and ballast.

He had a mainsail with a short gaff, a staysail, and a spinnaker of parachute material.

He used a small stove to make coffee and to warm food, and he’d loaded 35gal of water, four gallons of wine, four quarts of whisky, and 150gal of gasoline, stowing this intentionally for stability and ballast.

The Florentino Das commemorative marker at Kewalo Basin in Honolulu, Hawai’i, dedicated 2006. Credit: Serafin P. Colmenares, Jr

He also had a small motorcycle wedged in one compartment for when he reached the Philippines.

To begin with, he couldn’t get his boat to steer itself, so Das became terribly sleep-deprived.

Continuing west, the winds mostly favourable, he watched the sky for Hawaiʻi-bound aircraft to confirm his bearings.

There was little rain, so he worried about his supply of drinking water.

In calms, Das constructed a higher bracket for the motors, because they were getting too wet when not in use and needed constant attention.

He rebuilt one of the ignitions.

His watch set to GMT stopped, but he still felt he had a reasonable sense of where he was, so he steered north of west, to stay above the Marshall Islands to avoid the reefs.

Soon Florentino Das got the idea to rig up to his battery an old car radio that he had aboard.

In calms, Das constructed a higher bracket for the motors, because they were getting too wet when not in use and needed constant attention.

He rebuilt one of the ignitions.

His watch set to GMT stopped, but he still felt he had a reasonable sense of where he was, so he steered north of west, to stay above the Marshall Islands to avoid the reefs.

Soon Florentino Das got the idea to rig up to his battery an old car radio that he had aboard.

Relatives and friends of Florentino Das pose beside his statue in his hometown of Allen, Northern Samar, at its dedication in 2018.

Credit: Courtesy of Pio Arce

He managed to make this work, using the mast stays as an antenna.

Sixteen days out from Oahu he tuned in to a radio station from Japan, then one from Hawaiʻi, from which he was able to reset his GMT watch on their time signal and calculate his longitude.

Meanwhile, Lady Timarau was leaking around the centreboard trunk, requiring regular repairs to the bilge pump to keep ahead of it.

But once Das figured out a system of how to get the boat to steer itself, all was going pretty well.

He wrote on 3 June 1955: “I have been a good boy all my life, so I guess the good Lord will not leave me in the lurch. I am not a bit worried.”

But conditions worsened in the weeks that followed.

Meanwhile, Lady Timarau was leaking around the centreboard trunk, requiring regular repairs to the bilge pump to keep ahead of it.

But once Das figured out a system of how to get the boat to steer itself, all was going pretty well.

He wrote on 3 June 1955: “I have been a good boy all my life, so I guess the good Lord will not leave me in the lurch. I am not a bit worried.”

But conditions worsened in the weeks that followed.

The engines sputtered out of commission and the hull leaked so badly that he had to pump almost continuously.

On 19 June, Florentino Das signalled a Japanese fishing boat that towed him for about 500 miles to a harbour on the island of Pohnpei.

When he requested money for repairs from his sponsors in Hawaiʻi, some tried to raise funds, while others asked him to abandon the voyage.

Das felt obligated to continue, saying in a radio interview that he “wanted to prove that Filipinos are not only good boxers but also good boatbuilders and sailors.”

Das spent eight months in Pohnpei, repairing his boat and waiting out the typhoon season, until he continued for the second half of his voyage, stopping in the Chuuk Islands.

He made landfall in Yap, where he stayed for a few weeks before his final approach to the Philippines.

On 19 June, Florentino Das signalled a Japanese fishing boat that towed him for about 500 miles to a harbour on the island of Pohnpei.

When he requested money for repairs from his sponsors in Hawaiʻi, some tried to raise funds, while others asked him to abandon the voyage.

Das felt obligated to continue, saying in a radio interview that he “wanted to prove that Filipinos are not only good boxers but also good boatbuilders and sailors.”

Das spent eight months in Pohnpei, repairing his boat and waiting out the typhoon season, until he continued for the second half of his voyage, stopping in the Chuuk Islands.

He made landfall in Yap, where he stayed for a few weeks before his final approach to the Philippines.

Richard J King’s book features a chapter on Florentino Das

He managed to scoot south of the path of Typhoon Thelma, but still, he and Lady Timarau were battered by winds and seas until he anchored off a beach at Siargao Island on 25 April 1956, completing a 346-day, 4,700-mile odyssey.

Florentino Das continued to his home in Samar. From here he was escorted by the Philippine Navy and Coast Guard to Manila, where the new hero was paraded through the streets.

Das was awarded the Legion of Honour, named an honorary Commodore of the Philippine Navy, and was given the keys to Manila.

Back in Hawaiʻi there was a large banquet for his wife, who was named ‘Mother of the Year’.

A fund was set up in Honolulu to raise money to send the whole family to Manila. Yet the celebrations flared out too quickly.

Florentino Das was never able to gain any financial footing.

The fund in Hawaiʻi couldn’t raise enough money.

As the years went on, he and his wife agreed to divorce so she could remarry someone in Hawaiʻi with an income.

Das remarried, too, but he remained poor, and he began to lose his eyesight from complications of diabetes and high blood pressure.

In 1962 Lady Timarau sank at the dock in a hurricane. In 1964, at only 46 years old, the adventurer died of organ failure.

Though the name of Florentino Das is rarely mentioned in yachting books, there are two humble monuments to his voyage in the Philippines, a plaque in Honolulu and Hawaiʻi’s Filipino Community Center keeps a scale model of Lady Timarau.

On Siargao Island, Das’s arrival is celebrated annually as ‘Lone Voyagers Day’.

Most importantly, for his descendants in Hawaiʻi and the Philippines, the heroism of his solo voyage remains an inspiring example of one individual’s success, a fulfilment of a personal dream and a true shoestring voyage, while it is valued still more as an achievement for the Filipino people and a triumph of faith.

Links :

As the years went on, he and his wife agreed to divorce so she could remarry someone in Hawaiʻi with an income.

Das remarried, too, but he remained poor, and he began to lose his eyesight from complications of diabetes and high blood pressure.

In 1962 Lady Timarau sank at the dock in a hurricane. In 1964, at only 46 years old, the adventurer died of organ failure.

Though the name of Florentino Das is rarely mentioned in yachting books, there are two humble monuments to his voyage in the Philippines, a plaque in Honolulu and Hawaiʻi’s Filipino Community Center keeps a scale model of Lady Timarau.

On Siargao Island, Das’s arrival is celebrated annually as ‘Lone Voyagers Day’.

Most importantly, for his descendants in Hawaiʻi and the Philippines, the heroism of his solo voyage remains an inspiring example of one individual’s success, a fulfilment of a personal dream and a true shoestring voyage, while it is valued still more as an achievement for the Filipino people and a triumph of faith.

Links :

- Bold Dream: Uncommon Valor, The Florentino Das Story by Serafin P Colmenares Jr, Cecilia D Noble, and Patricia E Halagao

Wednesday, January 28, 2026

China built a $50 billion military stronghold in the South China Sea

Hainan Island

Hainan, a palm-fringed island known as China’s Hawaii, sits in the warm tropical waters of the South China Sea east of Vietnam.

It’s a popular tourist destination with soft-sand beaches, quaint mountain villages and fancy seaside resorts.

But just 500 feet from the lush grounds of the Holiday Inn Resort Yalong Bay is East Yulin Naval Base, home to Chinese destroyers and nuclear-armed submarines.

Welcome to Hainan.

China has spent tens of billions of dollars turning farm fields and commercial seaports into military complexes to project power across thousands of miles of ocean it claims as its own.

The military buildup has a variety of motives, experts say:

- Beijing’s quest for global power.

- Protection of sea routes that fuel China’s economy.

- Resource exploitation.

- And the ability to defeat the United States and its allies if they try to thwart a Chinese attack on Taiwan.

Over two decades, the People’s Liberation Army has more than tripled the value of its military infrastructure on Hainan and on reclaimed reefs in the South China Sea, according to an exclusive analysis of some 200 military sites by the Long Term Strategy Group (LTSG), a defense consultancy commissioned by the Defense Department that was authorized to share its analysis of open-source data with The Washington Post.

Overall, the value of the military infrastructure on Hainan and in the South China Sea exceeded $50 billion as of 2022, according to the researchers.

Overall, the value of the military infrastructure on Hainan and in the South China Sea exceeded $50 billion as of 2022, according to the researchers.

That’s more than the value of all U.S. military facilities in Hawaii, LTSG said.

The infrastructure at Greater Yulin Naval Base on Hainan was valued in 2022 at more than $18 billion, which rivals the value of one of the U.S. military’s most vital Pacific Ocean installations: Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, the researchers said.

(That figure does not include the underground submarine pen carved out of a mountain on the East Yulin base.)

Hainan, China’s southernmost province, now boasts a military support apparatus — buttressed by staggering infrastructure investments in the South China Sea — that analysts say could, if present trends continue, neutralize what has long been considered a U.S. military advantage in a possible head-to-head conflict.

The infrastructure at Greater Yulin Naval Base on Hainan was valued in 2022 at more than $18 billion, which rivals the value of one of the U.S. military’s most vital Pacific Ocean installations: Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, the researchers said.

(That figure does not include the underground submarine pen carved out of a mountain on the East Yulin base.)

Hainan, China’s southernmost province, now boasts a military support apparatus — buttressed by staggering infrastructure investments in the South China Sea — that analysts say could, if present trends continue, neutralize what has long been considered a U.S. military advantage in a possible head-to-head conflict.

Areas where China has invested in military infrastructure on Hainan Island from 2003 to 2022.

“It’s a profound challenge to the region. It’s a profound challenge to our allies and partners,” Adm. Samuel Paparo, commander of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, said in an interview.

“There’s no denying that the increase in the capability within the South China Sea ... is a threat ... to U.S. interests.”

Dadonghai Beach in Sanya, Hainan's southernmost city and a popular tourist destination.

Dadonghai Beach in Sanya, Hainan's southernmost city and a popular tourist destination.Sanya is also home to the Greater Yulin Naval Base.

(Hector Retamal/AFP/Getty Images)

Senior U.S. military officials do not think Chinese leader Xi Jinping is ready to mount an attack that would draw in American forces.

But that doesn’t mean the day won’t come — perhaps sooner rather than later.

“China is working very hard at having superiorities there that nobody else can match,” said retired Rear Adm. Michael Studeman, former commander of the Office of Naval Intelligence.

“They’ve built an ability to project power with multiple types of capabilities — air, missile, militia, ships, submarines,” he said.

“And we need to build up our capability and military posture with allies to forestall a Chinese attack.”

China’s staggering military buildup

The Greater Yulin Naval Base is the epicenter of the Chinese naval presence in the South China Sea, split across two deepwater bays and featuring the two most expensive military infrastructure items in the region today: an aircraft carrier dry dock and a carrier pier, together worth about $2.5 billion, according to LTSG estimates.

“They’ve built an ability to project power with multiple types of capabilities — air, missile, militia, ships, submarines,” he said.

“And we need to build up our capability and military posture with allies to forestall a Chinese attack.”

China’s staggering military buildup

The Greater Yulin Naval Base is the epicenter of the Chinese naval presence in the South China Sea, split across two deepwater bays and featuring the two most expensive military infrastructure items in the region today: an aircraft carrier dry dock and a carrier pier, together worth about $2.5 billion, according to LTSG estimates.

Map of greater Yulin naval base

Degaussing pier

East Yulin Naval Base houses China’s only ballistic-missile submarine base — a premier facility that provides part of the nation’s strategic nuclear deterrent.

CN303001 scale 1:90000 Wuchang port to Sanya Port

localization of Yulin Naval Base

Just south of a complex of six piers is a large cave built into a hillside that is designed to house multiple submarines deep underground and out of sight of surveillance satellites.

Farther south is a degaussing facility that reduces PLA Navy vessels’ magnetic signatures, making them less detectable to anti-submarine aircraft and helping protect from mines.

The base also houses multiple weapons storage depots, with more under construction, and the entire naval complex is defended by anti-ship and surface-to-air missile batteries.

Farther south is a degaussing facility that reduces PLA Navy vessels’ magnetic signatures, making them less detectable to anti-submarine aircraft and helping protect from mines.

The base also houses multiple weapons storage depots, with more under construction, and the entire naval complex is defended by anti-ship and surface-to-air missile batteries.

An aircraft carrier pier, just under a half-mile in length, was completed in 2013 at West Yulin Naval Base.

(Satellite image ©2024 Maxar Technologies)

A 2020 satellite image of a submarine entering a cave at East Yulin Naval Base.

A 2020 satellite image of a submarine entering a cave at East Yulin Naval Base.(Planet Labs)

A satellite image of the dry docks at West Yulin Naval Base in 2023.

(CNES/Airbus/Google Earth)

(CNES/Airbus/Google Earth)

A degaussing pier, built in 2008, minimizes the magnetic signature of vessels.

A degaussing pier, built in 2008, minimizes the magnetic signature of vessels.(Satellite image ©2024 Maxar Technologies)

But Hainan’s military development isn’t limited to the high seas.

Two decades ago, a U.S. EP-3 reconnaissance plane was hit by a Chinese fighter jet and made an emergency landing at Hainan’s Lingshui Air Base — then a single narrow runway, dotted with Soviet-era jets and flanked by palm trees.

Today, with modernization, that base is estimated to be worth $1.65 billion, and it boasts anti-submarine warfare aircraft, airborne early warning craft and a new munitions storage area.

It is now one of three major military airfields on the island.

Time-lapse images depicting the development of Linghsui Air Base over 10 years.

Time-lapse images depicting the development of Linghsui Air Base over 10 years.(CNES/Airbus and Max Technologies/Google Earth)

In addition, some 125 miles up the coast to the northeast lies the PLA’s Wenchang space launch facility, which China touts as its “portal to space in the 21st century.”

The military launches satellites from Wenchang for communications, reconnaissance and surveillance purposes.

With an inaugural launch in 2016, Wenchang is China’s only spaceport on a coast — the three others are in remote regions such as Inner Mongolia and Shanxi province.

Wenchang’s position closer to the equator gives rockets a performance boost gained from the Earth’s rotational speed.

China’s latest, largest space modules can be launched only from Wenchang, and the spaceport aims to send astronauts to the moon by 2030.

With an inaugural launch in 2016, Wenchang is China’s only spaceport on a coast — the three others are in remote regions such as Inner Mongolia and Shanxi province.

Wenchang’s position closer to the equator gives rockets a performance boost gained from the Earth’s rotational speed.

China’s latest, largest space modules can be launched only from Wenchang, and the spaceport aims to send astronauts to the moon by 2030.

A rocket carrying a communications satellite takes off from the Wenchang space launch facility on March 20.

(Xinhua News Agency/Getty Images)

(Xinhua News Agency/Getty Images)

Hainan also boasts a PLA Rocket Force base, one of more than 40 such facilities across the country.

Built in 2019, the base houses DF-21D anti-ship ballistic missiles, according to Decker Eveleth, a specialist on Chinese nuclear and missile programs at CNA, a think tank based in Arlington, Virginia.

Known as “carrier killers,” these conventionally armed weapons can travel more than 900 miles, enabling the PLA to conduct precision strikes against ships as far away as the western Pacific, Eveleth said.

Just last month, the Rocket Force launched from a site north of Wenchang an intercontinental ballistic missile with a dummy warhead that flew some 7,400 miles before landing in the South Pacific— the first such launch by China in more than 40 years.

Just last month, the Rocket Force launched from a site north of Wenchang an intercontinental ballistic missile with a dummy warhead that flew some 7,400 miles before landing in the South Pacific— the first such launch by China in more than 40 years.

Time-lapse images depicting the development of the PLA Rocket Force base on Hainan.

Time-lapse images depicting the development of the PLA Rocket Force base on Hainan. (The Washington Post)

The Hainan air bases provide cover for China’s fleet of ships, said Thomas Shugart, an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security and former Navy submarine warfare officer.

They are part of what is known as a layered military posture: While the PLA navy roams the South China Sea, submarines can interdict enemy forces and conduct reconnaissance ahead of the fleet.

Fighter jets provide air support and ward off advance threats, while missiles from the Rocket Force provide long-range cover.

“It is a comprehensive set of infrastructure that covers every domain of conflict on, over and under the South China Sea,” Shugart said.

“And all this will be very hard to neutralize, especially during a major conflict over the Taiwan Strait.”

The new flash point

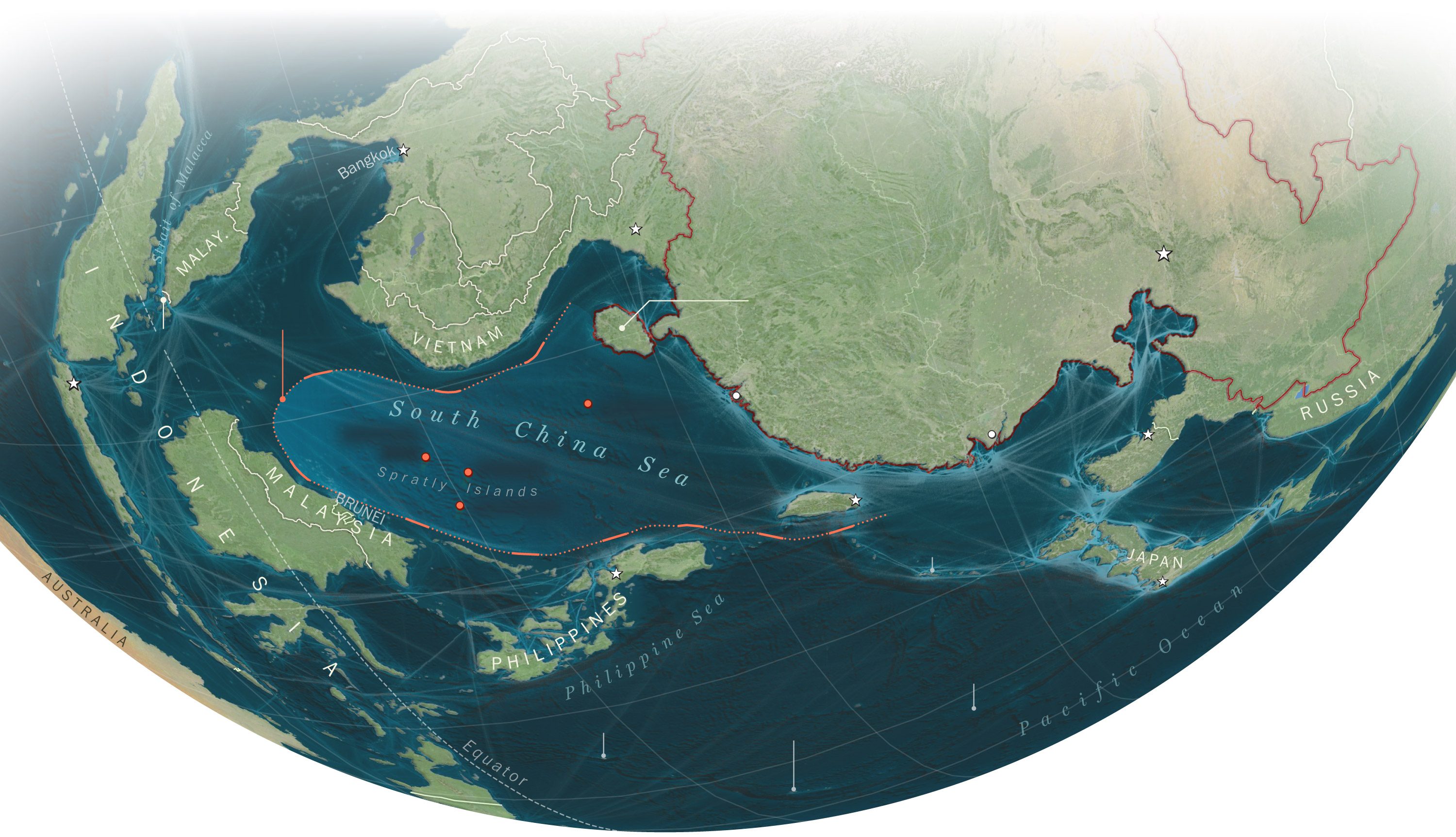

Hainan and the South China Sea lie in the southern reaches of what is sometimes called the First Island Chain, an area that arcs south from the Japanese archipelago, along the coasts of Taiwan and the northern Philippines, and then curves up along Malaysia and Brunei on the island of Borneo and north to Vietnam, in a giant fishhook pattern.

Much of this geographical boundary overlaps with China’s “10-Dash Line,” or the margins of what it claims as its maritime dominion.

A long-standing PLA objective is to achieve the capability of “breakout” power projection along its entire maritime flank, from the Sea of Japan (or East Sea) down through the South China Sea, Studeman said.

Beijing believes that the only way to protect its strategic lifelines, secure offshore resources and keep enemies at bay is to establish effective control inside much of the area demarcated by the First Island Chain, he said.

That would be the first step in a strategic playbook to extend its power into the broader Pacific and the Indian and Arctic oceans, he said.

“China’s fever for domination in its near-abroad has become the most destabilizing trend in the Indo-Pacific,” he said.

Perspective view of the South China Sea showing ship traffic density

The 10-dash line, China's maritime claim in the South China Sea

In the past 10 years, China has built up island outposts in the South China Sea to extend its reach and assert dominance over these trade routes.

Democratic allies and partners of the United States — including the Philippines, Taiwan and Japan — lie along the First Island Chain and contest China’s militarization of the waters.

Farther east in the Pacific, along the Second Island Chain, lie major U.S. military bases.

China’s militarized outposts are designed to restrict the ability of the United States and its allies to enter Beijing’s claimed zone of influence.

Some $7.4 trillion in trade flows through the waters of the South China Sea and the East China Sea each year — at least as of 2019, before the global pandemic disrupted supply chains — according to a 2023 Duke University report led by scholar Lincoln Pratson.

Most of the fuel and other resources that China needs come from the Middle East and Africa through these seas — as does about 80 percent of its trade.

“If you have a conflict there, up to 30 percent of world trade in oil would be affected,” Pratson said.

The hottest flash point in the South China Sea of late has been near the Philippines, where Chinese coast guard vessels in June clashed with Philippine navy boats trying to resupply a rusted warship anchored at Second Thomas Shoal — an outpost in the Spratly Islands that both countries claim.

The fracas became an international incident, prompting outrage from the Philippines and pledges by the United States that it would back its treaty ally if events escalated.

In August, coast guard ships from China and the Philippines twice collided near Sabina Shoal, another disputed area in the Spratly Islands.

If the clashes escalated into a shooting war, and the United States came to the Philippines’ defense, the nearest U.S. air bases are Andersen Air Force Base on Guam — a U.S. territory some 1,900 miles from Second Thomas Shoal — and Kadena Air Base on the island of Okinawa in Japan, 1,400 miles away.

Hainan, by contrast, is 800 miles away.

But just 18 nautical miles away is Mischief Reef, where China has an air base valued at more than $3.5 billion, according to LTSG.

Satellite images of the Chinese outposts in the South China Sea

Over the past decade, China has conducted a massive buildup of military installations across the South China Sea, from the Paracel to the Spratly Islands, including turning uninhabited atolls into islands bristling with military assets.

An international tribunal in 2016 found the buildup illegal.

LTSG pegged the value of these Chinese bases in 2022 at $15 billion, surpassing the value of all U.S.

military infrastructure on Guam.

“There’s a reason why China can be so aggressive in the Philippines,” Shugart said.

“In any level of conflict China has with the Philippines and with the United States, we would really have to ramp it up in a very significant way.”

Paparo, the top commander of U.S. forces in the Indo-Pacific region, noted China’s respectable arsenal.

“There’s no denying the quantity of capability that [China] has put on Hainan island,” Paparo said, running through a list that includes six nuclear-powered ballistic-missile submarines, a destroyer flotilla, two fighter regiments, a ballistic-missile brigade, two attack submarine squadrons, two airfields, two naval bases, a coastal defense brigade and a combined arms brigade.

Though the United States, with ships and aircraft in the Pacific, is always ready to defend its allies and interests if China attacks, Paparo said, more must be done.

“We have got to step up our investment in the defense industrial base and in our defense infrastructure,” he said, “in order to deter conflict with credible, decisive combat power.”

Links :

About this story

To estimate the dollar value of PLA infrastructure, LTSG categorized and measured each structure at some 200 sites through the use of satellite imagery.

It applied a standard Defense Department metric called “plant replacement value,” which approximates the cost to replace a structure in 2023 dollars.

All figures are set to U.S. national average prices, enabling comparisons between U.S. and Chinese infrastructure over time.

To estimate the dollar value of PLA infrastructure, LTSG categorized and measured each structure at some 200 sites through the use of satellite imagery.

It applied a standard Defense Department metric called “plant replacement value,” which approximates the cost to replace a structure in 2023 dollars.

All figures are set to U.S. national average prices, enabling comparisons between U.S. and Chinese infrastructure over time.

Tuesday, January 27, 2026

Thousands of Chinese fishing boats quietly form vast sea barriers

Between 23-28 Dec, 2025, 1700+ Chinese fishing vessels moved in the East Sea.

— Isabella Anderson (@IsabellaAn67) January 19, 2026

The Chinese fishing boats moved in military style coordination to form barriers, hundreds of miles in length.

The formation, the size of the fleet and the military style coordination was never seen… pic.twitter.com/URFBJqOQny

Between 23-28 Dec, 2025, 1700+ Chinese fishing vessels moved in the East Sea.

The Chinese fishing boats moved in military style coordination to form barriers, hundreds of miles in length.

The formation, the size of the fleet and the military style coordination was never seen before.

There is not doubt, China seeks to deploy these so called fishing boats during a crisis to block critical sea lanes.

From NYTimes by Chris Buckley, Agnes Chang and Amy Chang Chien

China quietly mobilized thousands of fishing boats twice in recent weeks to form massive floating barriers of at least 200 miles long, showing a new level of coordination that could give Beijing more ways to impose control in contested seas.

The two recent operations unfolded largely unnoticed. An analysis of ship-tracking data by The New York Times reveals the scale and complexity of the maneuvers for the first time.

Last week, about 1,400 Chinese vessels abruptly dropped their usual fishing activities or sailed out of their home ports and congregated in the East China Sea. By Jan. 11, they had assembled into a rectangle stretching more than 200 miles. The formation was so dense that some approaching cargo ships appeared to skirt around them or had to zigzag through, ship-tracking data showed.

Maritime and military experts said the maneuvers suggested that China was strengthening its maritime militia, which is made up of civilian fishing boats trained to join in military operations. They said the maneuvers show that Beijing can rapidly muster large numbers of the boats in disputed seas.

The Jan. 11 maneuver followed a similar operation last month, when about 2,000 Chinese fishing boats assembled in two long, parallel formations on Christmas Day in the East China Sea. Each stretched 290 miles long, about the distance from New York City to Buffalo, forming a reverse L shape, ship-position data indicates. The two gatherings, weeks apart in the same waters, suggested a coordinated effort, analysts said.

The unusual formations were spotted by Jason Wang, the chief operating officer of ingeniSPACE, a company that analyzes data, and were independently confirmed by The Times using ship-location data provided by Starboard Maritime Intelligence.

“I was thinking to myself, ‘This is not right’,” he said, describing his response when he spotted the fishing boats on Christmas Day. “I mean I’ve seen like a couple hundred — let’s say high hundreds,” he said, referring to Chinese boats he has previously tracked, “but nothing of this scale or of this distinctive formation.”

In a conflict or crisis, for instance over Taiwan, China could mobilize tens of thousands of civilian ships, including fishing boats, to clog sea lanes and complicate military and supply operations of its opponents.

Chinese fishing boats would be too small to effectively enforce a blockade. But they could possibly obstruct movement by American warships, said Lonnie Henley, a former U.S. intelligence officer who has studied China’s maritime militia.

The masses of the smaller boats could also act “as missile and torpedo decoys, overwhelming radars or drone sensors with too many targets,” said Thomas Shugart, a former U.S. naval officer now at the Center for a New American Security.

Analysts tracking the ships were struck by the scale of the maneuvers, even given China’s record of mobilizing civilian boats, which has involved anchoring boats for weeks on contested reefs, for instance, to project Beijing’s claims in territorial disputes.

“The sight of that many vessels operating in concert is staggering,” said Mark Douglas, an analyst at Starboard, a company with offices in New Zealand and the United States. Mr. Douglas said that he and his colleagues had “never seen a formation of this size and discipline before.”

“The level of coordination to get that many vessels into a formation like this is significant,” he said.

The assembled boats held relatively steady positions, rather than sailing in patterns typical of fishing, such as paths that loop or go back and forth, analysts said. The ship-location data draws on navigation signals broadcast by the vessels.

The operations appeared to mark a bold step in China’s efforts to train fishing boats to gather en masse, in order to impede or monitor other countries’ ships, or to help Beijing assert its territorial claims by establishing a perimeter, said Mr. Wang of ingeniSPACE.

“They’re scaling up, and that scaling indicates their ability to do better command and control of civilian ships,” he said.

The Chinese government has not said anything publicly about the fishing boats’ activities. The ship-signals data appeared to be reliable and not “spoofed” — that is, manipulated to create false impressions of the boats’ locations — Mr. Wang and Mr. Douglas both said.

Researchers at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, when approached by The Times with these findings, confirmed that they had observed the same packs of boats with their own ship-location analysis.

“They are almost certainly not fishing, and I can’t think of any explanation that isn’t state-directed,” Gregory Poling, the director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at C.S.I.S., wrote in emailed comments.

The fishing boats assembled in the East China Sea, near major shipping lanes that branch out from Shanghai, among the world’s busiest ports. Cargo ships crisscross the sea daily, including ones carrying Chinese exports to the United States.

These are maritime arteries that China would seek to control in a clash with the United States or its Asian allies, including in a possible crisis over Taiwan, the island-democracy that Beijing claims as its territory.

“My best guess is this was an exercise to see how the civilians would do if told to muster at scale in a future contingency, perhaps in support of quarantine, blockade, or other pressure tactics against Taiwan,” Mr. Poling wrote. A “quarantine” means a sea operation to seal off an area that is meant to fall short of an act of war.

The boat maneuvers in January took place shortly after Beijing held two days of military exercises around Taiwan, including practicing naval maneuvers to blockade the island. Beijing is also in a bitter dispute with Japan over its support for Taiwan.

The fishing boat operations could have been held to signal “opposition to Japan” or practice for possible confrontations with Japan or Taiwan, said Andrew S. Erickson, a professor at the U.S. Naval War College who studies China’s maritime activities. He noted that he spoke for himself, not for his college or the navy.

Japan’s Ministry of Defense and coast guard both declined to comment on the Chinese fishing boats, citing the need to protect their information-gathering capabilities.

Some of the fishing boats had taken part in previous maritime militia activities or belonged to fishing fleets known to be involved in militia activities, based on a scan of Chinese state media reports. China does not publish the names of most vessels in its maritime militia, making it difficult to identify the status of the boats involved.

But the tight coordination of the boats showed it was probably “an at-sea mobilization and exercise of maritime militia forces,” Professor Erickson said.

“They’re scaling up, and that scaling indicates their ability to do better command and control of civilian ships,” he said.

The Chinese government has not said anything publicly about the fishing boats’ activities. The ship-signals data appeared to be reliable and not “spoofed” — that is, manipulated to create false impressions of the boats’ locations — Mr. Wang and Mr. Douglas both said.

Researchers at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, when approached by The Times with these findings, confirmed that they had observed the same packs of boats with their own ship-location analysis.

“They are almost certainly not fishing, and I can’t think of any explanation that isn’t state-directed,” Gregory Poling, the director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at C.S.I.S., wrote in emailed comments.

The fishing boats assembled in the East China Sea, near major shipping lanes that branch out from Shanghai, among the world’s busiest ports. Cargo ships crisscross the sea daily, including ones carrying Chinese exports to the United States.

These are maritime arteries that China would seek to control in a clash with the United States or its Asian allies, including in a possible crisis over Taiwan, the island-democracy that Beijing claims as its territory.

“My best guess is this was an exercise to see how the civilians would do if told to muster at scale in a future contingency, perhaps in support of quarantine, blockade, or other pressure tactics against Taiwan,” Mr. Poling wrote. A “quarantine” means a sea operation to seal off an area that is meant to fall short of an act of war.

The boat maneuvers in January took place shortly after Beijing held two days of military exercises around Taiwan, including practicing naval maneuvers to blockade the island. Beijing is also in a bitter dispute with Japan over its support for Taiwan.

The fishing boat operations could have been held to signal “opposition to Japan” or practice for possible confrontations with Japan or Taiwan, said Andrew S. Erickson, a professor at the U.S. Naval War College who studies China’s maritime activities. He noted that he spoke for himself, not for his college or the navy.

Japan’s Ministry of Defense and coast guard both declined to comment on the Chinese fishing boats, citing the need to protect their information-gathering capabilities.

Some of the fishing boats had taken part in previous maritime militia activities or belonged to fishing fleets known to be involved in militia activities, based on a scan of Chinese state media reports. China does not publish the names of most vessels in its maritime militia, making it difficult to identify the status of the boats involved.

But the tight coordination of the boats showed it was probably “an at-sea mobilization and exercise of maritime militia forces,” Professor Erickson said.

Chinese-flagged ships anchored in contested waters of the South China Sea in 2023.

Jes Aznar for The New York Times

China has in recent years used maritime militia fishing boats in dozens or even hundreds to support its navy, sometimes by swarming, maneuvering dangerously close, and physically bumping other boats in disputes with other countries.

The recent massing of boats appeared to show that maritime militia units are becoming more organized and better equipped with navigation and communications technology.

“It does mark an improvement in their ability to marshal and control a large number of militia vessels,” said Mr. Henley, the former U.S. intelligence officer, who is now a non-resident senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Philadelphia. “That’s one of the main challenges to making the maritime militia a useful tool for either combat support or sovereignty protection.”

Choe Sang-Hun contributed reporting from Seoul and Javier C. Hernández and Kiuko Notoya contributed reporting from Tokyo.

Data source: Starboard Maritime Intelligence.

About the data: We analyzed automatic identification systems (AIS) data of ships that broadcast positions near the formation in the 24-hour periods of Dec. 25, 2025 and Jan. 11, 2026 that either follow China’s fishing ship naming convention or are registered as China-flagged fishing vessels. Ships do not always transmit information and may transmit incorrect information. The positions shown in maps are last known positions at the specific times.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)