A fellow cruiser at anchor in the harbor at Vis

From SailMagazine by Eric Vohr (Photos by Michaela Urban)As is the case with so much of the Mediterranean, to sail in Croatia is to take a journey through time.

Centuries before the birth of Christ, Greeks traded amphoras of oil, wine and grain across these waters.

During the first millennium, the Romans built lavish palaces and fortresses here.

More recently, the islands of the Adriatic have been home to secret WWII airbases and Cold War military installations.

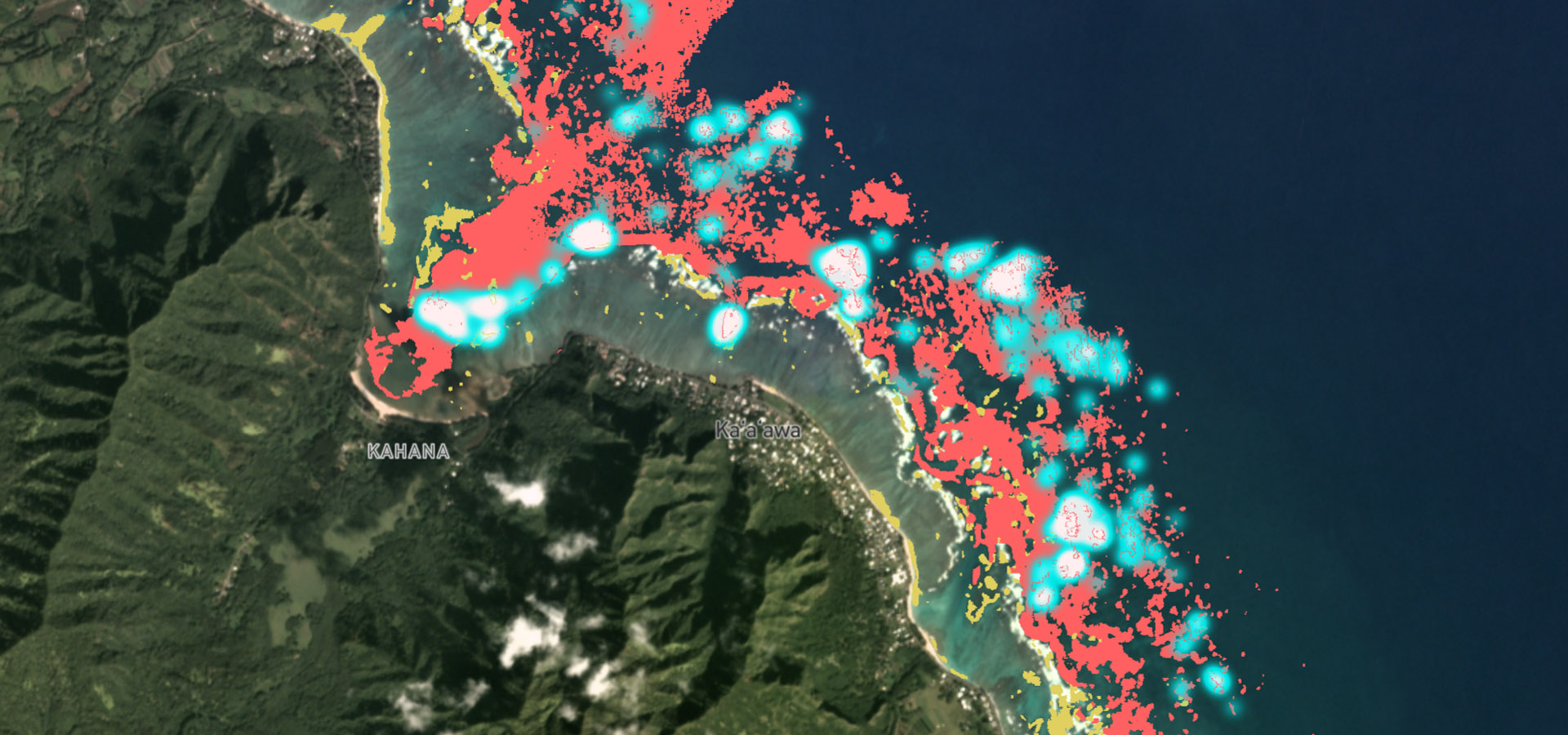

ENC rasterised nautical charts in the GeoGarage platform

Eager to explore these ancient mysteries and bask in the region’s cerulean blue waters, quaint stone villages and lush green groves of olive and pomegranate, my partner, Michaela, and I set sail one fall to tour the many islands that lie off the coast of Split.

There's nothing like warm water and a fair breeze on charter !

We chartered with Sail Croatia (

sail-croatia.com) in the ACI Marina in Split, which provided us with a fully-loaded, Beneteau Oceanis 41.

Before heading out, we did our homework, especially with regard to the variable winds in this part of the world, each of which has its own name—Bura, Jugo, Maestral, Levant, Tramontana, Oštro, Lebić and Pulenat.

We needed to be particularly aware of the northeast Bura and the southeast Jugo, both of which can be especially strong in fall and winter.

The Bura has been clocked at 150 knots, equal to a Category 5 hurricane, and even the less-intense Jugo can sometimes dish out 50-knot winds and 15ft seas.

If ever one of these winds is forecast, seek shelter, preferably in a marina.

Luckily, Sail Croatia provided us with a very thorough briefing and free Wi-Fi onboard, allowing us to get up-to-date weather reports around the clock.

Diving a 2,000-year-old wreck near Vis

We also made sure to plot our overnights well in advance and even pre-book in any especially popular destinations.

Coastal Croatia can get pretty busy, and with the steep shorelines you encounter there, we knew we wouldn’t find even half as many places to drop a hook as in the Caribbean.

Luckily, there are quite a few mooring balls scattered, and given we would be chartering during the off-season, we figured we’d be alright, as long as we didn’t arrive at any of our destinations too late.

Our first destination, Vis, is roughly 30 miles from Split, which is doable, but a long sail.

So we decided to break it up and stop in at a wonderful little bay on the eastern end of Solta island called Uvala Sesula.

It’s an easy 11 miles from the base and provides good shelter in most weather conditions.

There are also two great restaurants there that have mooring balls we could reserve in advance for free with a dinner reservation, a common routine in Croatia.

A closeup of a gunboat tunnel

Our first day out was an easy one with an 8 to 12-knot breeze on the beam that took us right to the mouth of the bay.

As we made our approach, we radioed in and one of the staff at Konoba Sesula came out to help us secure our boat.

(“Konoba” is the local term for a restaurant that serves traditional food.) Afterward, we took a narrow foot path over to the quaint fishing village of Maslinica, which has a lovely little harbor, more restaurants and cafés, and a number of grocery stores for last-minute provisioning.

The following morning the wind clocked a little south and then steadily increased throughout the day, providing a rather spirited close-reach and getting us into the lovely main port of Vis by early afternoon.

The town of Vis, which borrows its name from the island, is on the northern side of the island.

There is a large mooring field and a number of marinas that were all pretty empty when we arrived, but filled up considerably by sundown.

Due to its strategic position, Vis played a key role during both WWII and the Cold War.

In the 1940s, it was the site of a crucial emergency airbase for crippled Allied bombers.

In the 1980s, Yugoslav leader Josip “Tito” Broz built a pair of clandestine military bases both here and in neighboring island of Lastovo.

On our first full day on Vis we planned to explore the remains of a few of these military sites.

But while shopping for a scooter rental, we learned that many of them are poorly marked and therefore hard to find.

We were then directed to the local tour company Alternatura, run by Pino Vojkovic, who apparently was the “go-to guy” for military tours of the island.

The following morning we climbed aboard one of Pino’s signature blue Land Rovers and drove to a high vantage point where our guide, Goran, pointed out the ghost-like remnants of the now completely overgrown airstrip Allied bombers once made their emergency landings.

We also toured a small shop that now serves as a kind of de facto museum of ancient bomber wings, propellers, parachutes and other odd parts left behind by the Allies.

From there we drove to Cape Stupišće, where Goran took us down an impossibly rutted dirt road leading to a large clearing hidden by rotted camouflage netting.

Goran explained that this is where Tito hid the enormous trucks that served as both transport vehicles and launching platforms for his country’s Soviet-made, surface-to-air missiles.

He then handed us helmets and headlamps, and we entered the eerie darkness of one of the tunnels used to store these kinds of missiles.

Inside we found bunkers with foot-thick steel doors on greased hinges and explored narrow escape routes that terminated in small rock shelters disguised to look like shepherd outposts.

It was all like something out of a James Bond movie.

After that came ARK Vela Glava the headquarters for Tito’s operations in Vis and the island’s largest network of tunnels.

These tunnels were much darker and deeper and led to a network of side tunnels and rooms that once housed troop barracks and ammunition stores.

At the end of one of these tunnels we exited into the blinding sun only to find a decrepit gun battery aimed directly across the Adriatic in the direction of Italy.

Of course, the rich history of Vis is not only found on land, and our next stop was the local dive company, Nautica Vis Diving Center.

On one of our dives we got up close and personal with a U.S.

bomber that had sunk during the war.

Apparently, the now coral-encrusted B-24 had been circling the island trying to get its landing gear down when it ran out of fuel.

As the story goes, the captain first let his crew bail out before attempting a crash landing, a heroic maneuver he tragically didn’t survive.

Another dive took us to the wreck of an ancient trading vessel that pre-dates Christ.

Nothing was left of the actual ship.

But a large assortment of amphoras remains, many of them intact and presumably still full of their ancient cargo.

On our last day on the island, we took a relaxed scooter ride along Vis’s rock-strewn landscape dotted with wild rosemary bushes and chicory, thistle and rockrose flowers.

One of our stops, Komiža, the island’s other port town on the opposite side, has a wonderful selection of outdoor cafes along its historic harbor front.

We also explored a site called the Queen's Cave, near the abandoned village of Okijunca.

The trail there is poorly marked, so if you don’t like getting lost, you might want to hire a guide to take you there.

Okijunca itself makes for fantastic exploring with its small Capella and empty stone houses overlooking dark-green olive groves and the expansive sapphire waters of the Adriatic.

Before moving on, we spent a night in Blue Lagoon, a sheltered harbor on the western shore of Budikovac Island just off the southeast corner of Vis.

This beautiful little anchorage provided a wonderful respite before the long sail to our next port-of-call, Lastovo.

There are plenty of mooring balls here, a nice beach and a friendly family-run restaurant.

Although the bay is popular with day cruises, it largely empties out at night.

Lastovo is about 40 mile southeast of Vis, and the scattering of beautiful islands off its eastern end creates a spectacular entryway.

One of Lastovo’s larger Cold War military bases is located in Jurjeva Bay—a well-sheltered anchorage on the nearby island of Prezxba.

Jurjeva Bay has a nice little beach and is surrounded by an assortment of abandoned buildings and guard towers.

Exploring on the southern side of the bay, we stumbled upon a small entrance in a rock face that led to another one of Tito’s extensive tunnel systems.

Carefully watching our step and avoiding the ghostly camel crickets (that looked even more monstrous by the light of our headlamps), we picked our way down a long dark corridor and eventually came to a large munitions area similar to what we’d seen at Cape Stupi.

We also found evidence of troop quarters—barracks, ventilation equipment, old generator stands and bathrooms.

It wasn’t until we exited that we saw the small sign prohibiting entrance, so explore at your own risk.

Having had our fill of damp, dark tunnels, we re-energized our bodies in the warm Croatian sun by scrambling up an unmarked trail leading south to yet another bay called Uvala Kremena.

Here we found one of the sea tunnels carved out of the mountain that Tito used for hiding his gunboats.

There are a number of these on Lastovo and Vis that yachties now like to use for overnight stays, although it was not clear to us whether doing so was 100 percent legal.

Satisfied with our rather extensive military tour, our next stop was the lively port of Zaklopatica, a wonderfully sheltered bay on Lastovo’s northern shore and the site of an equally wonderful marina and restaurant called the Konoba Triton, a popular sailors’ hangout.

In Zaklopatica I also had a chance to practice my docking skills in front of a good-sized crowd, an experience that was not for the faint of heart.

The process was essentially “Med mooring,” except instead of dropping an anchor before reversing, there was a set of permanent bow lines you retrieved via a messenger line.

Split

The following morning, we explored the small village of Lastovo, within easy walking distance of Zaklopatica.

The town sits in a protected valley facing inland away from the sea and includes a collection of beautiful old stone houses perched on terraced streets.

Due to a slump in the local economy, much of the town appeared to have been abandoned or in serious disrepair, stimulating my ever-present urge to sell it all and start a café or hotel in precisely this kind of peaceful corner of the world.

The author prepares for one of the area’s notorious Buras

From Lastovo, we continued on to one of our favorite destinations of the entire trip, Fisherman’s House/Pension Tonci on Sveti Klement in the Pakleni Otoci Islands.

Located roughly 30 miles northwest of Lastovo on the western end Hvar, Fisherman’s House is run by the Matijević family and is the quintessential relaxed, bucolic Croatian island retreat, complete with its own vineyard and vegetable gardens.

In fact, we loved Fisherman’s House so much, we originally decided to spend our last couple of nights there, sunbathing and soaking in the relaxed life of the Adriatic.

However, nasty weather was approaching, which our host said would likely turn into a Bura, in which case our wonderful little bay on Sveti Klement would provide limited shelter at best.

He recommended we shift to a marina in Milna and the much better protected harbor on Brac.

Without hesitation, we called to book a slip.

The weather was relatively calm when we arrived there, but it was amazing how quickly the storm hit.

After securing our boat, I was ashore taking a leisurely stroll along the waterfront when a few paper bags and paper trash started spinning in circles around me.

I didn’t think much of it until a patrons in a nearby restaurant told me to take cover—fast—prompting me to make a bee-line back to our boat.

The storm hit minutes later with torrential rain and such violent winds some of the crews taking shelter in the harbor had to adjust lines to prevent their sterns quarters from hitting the pier.

Afterward, when the storm had passed, Milna’s many quaint restaurants, bars and clubs quickly came back to life.

Milna is a picture-postcard, classic Croatia seaside town, with its classic stone architecture and baroque church with a characteristic Dalmatian bell tower.

The surrounding countryside is equally enchanting, consisting of a patchwork of old stone farms and picturesque orchards.

Sadly, Milna represented the end of our charter.

It was also time to top up our fuel tanks, something we wanted to do while still out among the islands to avoid the long lines and general mayhem we’d seen at the fuel dock in Split.

Unfortunately, we ended up facing the same problem in Milna—boats drifting into each other, no real system or queue, plenty of screaming and short tempers.

I’m guessing the only way to avoid this kind of chaos is to fill up out on the islands late Thursday night or super early Friday morning.

Anyway, we survived.

Once safely back in the harbor of Split, we spent a few days exploring the city with its old Roman Palace and narrow alleys.

We stayed at Divota, a wonderful hotel that included some of the magnificently restored century-old stone houses in the ancient neighborhood.

If you prefer staying in the heart of the palace “compound,” as it’s called, the Marmot is nice as well.

For dinner, there are plenty of choices, but we particularly liked Articok, as the chef there is amazing.

Trattoria Tavulin is also located inside the palace “compound” and the outside seating there is nothing less than magical.

A place called Dujkin Dvor, along the waterfront, is an especially friendly local eatery where the owners regularly circulate among the guests, making it a great place to end your visit to this charming corner of the world.

Just be mindful of the weather and plan ahead.

You want to enjoy the history here, not become part of it!

The town of Lastovo sits nestled among the hills

Cruising Tips: Croatia

May through June and late September to October are the best times to sail in Croatia.

The weather is great, you avoid the crazy summer crowds, and you’ll find great deals and availability of boats.

The winds in Croatia blow for all directions, at all times of the day and year, and can change quickly, both in direction and intensity.

Be prepared to find safe harbor, preferably a marina, during rough weather.

Mooring balls are the norm, as most of the bays have steep shorelines and rocky bottoms.

Overnight wind shifts are also common.

Most of the smaller coves and bays offer free moorings to those who book a dinner at one of the restaurants ashore.

Croatia is Europe’s most popular sailing destination, so expect crowds, even off-season, and plan accordingly.

It’s not necessary to load up on provisions beforehand, as we found well-stocked stores and bakeries at many of the destinations we visited.

Croatia depends heavily on tourism and sailors, and you’ll find great restaurants almost everywhere you go, so be sure and give them a try.

Links :

From MaritimeCyprus

From MaritimeCyprus From MaritimeCyprus

From MaritimeCyprus

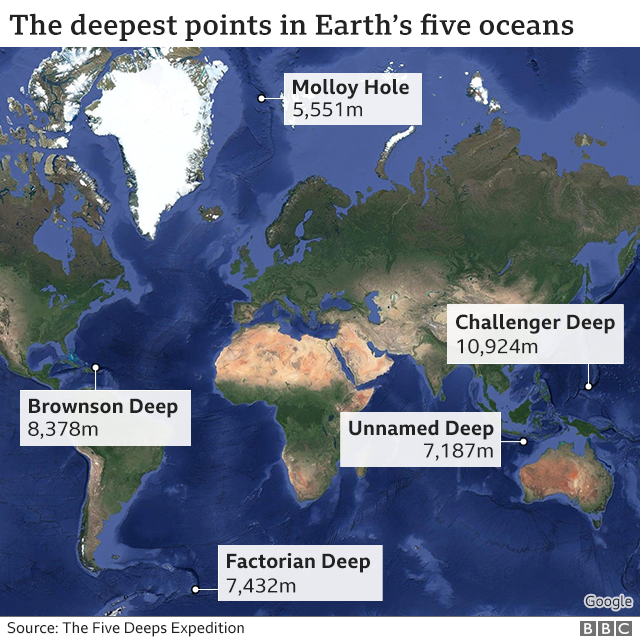

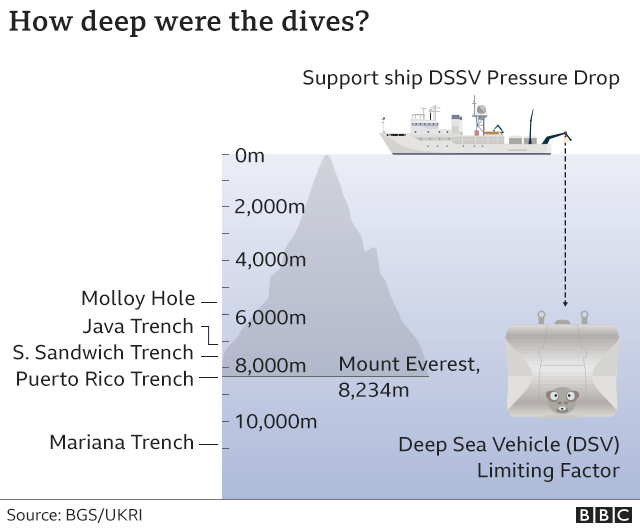

Mariana Trench: Deep ocean trenches occur where Earth's tectonic plates meet

Mariana Trench: Deep ocean trenches occur where Earth's tectonic plates meet

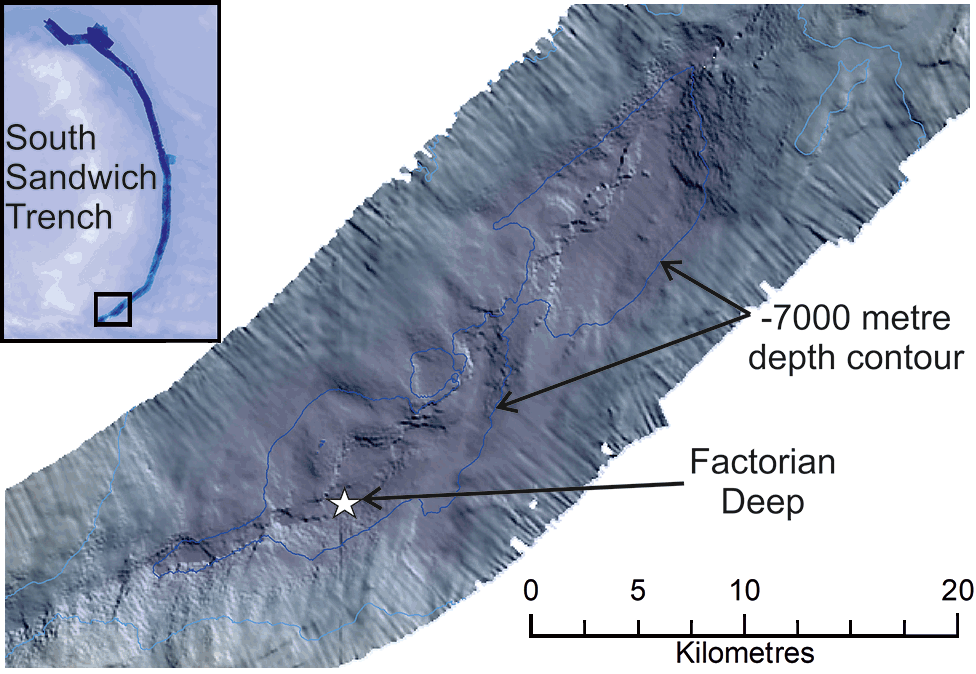

Factorian Deep is at 60.4 degrees South, and therefore just in the Southern Ocean

Factorian Deep is at 60.4 degrees South, and therefore just in the Southern Ocean