Havre seamount with the GeoGarage platform

(Linz nautical charts overlaid on Google Maps)

From Wired by Sian Bradley

In 2012, the Havre Seamount was the site of the largest underwater eruption of the century.

Now, high-resolution mapping of the ocean floor has revealed previously unknown behaviours of undersea volcanoes.

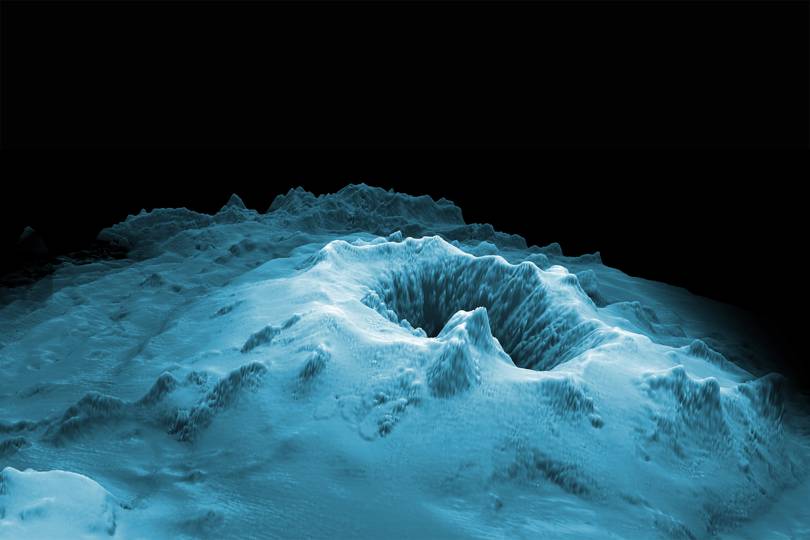

The remotely operated vehicle Jason (which is about the size of a large car), landing on the seafloor at Havre submarine volcano at 900 meters below sea level

University of Tasmania, Australia.

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute

A pair of autonomous underwater vehicles have helped uncover details of the biggest undersea eruption of the century.

The daring mission is helping to unlock the mysteries of a rarely-seen event and shed further light on underwater volcanism.

Guided by top volcanologists from the University of Tasmania, Australia, the vehicles plunged 650 meters below sea level to map the ocean floor, shedding light on a an eruption that occurred in 2002.

That eruption, of the Havre Seamount off the coast of New Zealand, released 400 square kilometres of porous volcanic rock, some of which floated to the surface.

Satellite imagery indicates that this sort of event happens about four times every 100 years – but is something that we rarely spot.

Now, volcanologists have delved beneath the surface, and answered questions that cameras above the ocean could not.

The Havre submarine volcano 650 meters below sea level, which was the site of the largest underwater eruption of the past century

University of Tasmania, Australia.

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute

“When we used the submersible vehicles to go down to the seafloor in 2015, we were able to see a vast array of new volcanic products, such as 14 different lava flows at depths of between 1,220 and 650 metres beneath sea level,” says Rebecca Carey, lead researcher on the study, which has been published in the journal Science Advances.

They were able to determine, for the first time, when the eruption happened and the volcanic processes that move magma from the crust to the surface.

Water pressure is so high at those depths that magma loses some of its energy during eruption.

“Hydrostatic pressure of the eruption column probably suppressed most of the explosivity that would have occurred if the volcano were on land,” Carey says.

“The eruption produced lava rather than a massive jet and eruption column that we see for land eruptions of this magnitude – such as Mount St.

Helens in 1980, or Chaiten volcano in 2008.” Their mapping has shown that around 80 per cent of the volcanic rock was dispersed into the Pacific Ocean, landing on Micronesian island beaches and the east Australian seaboard.

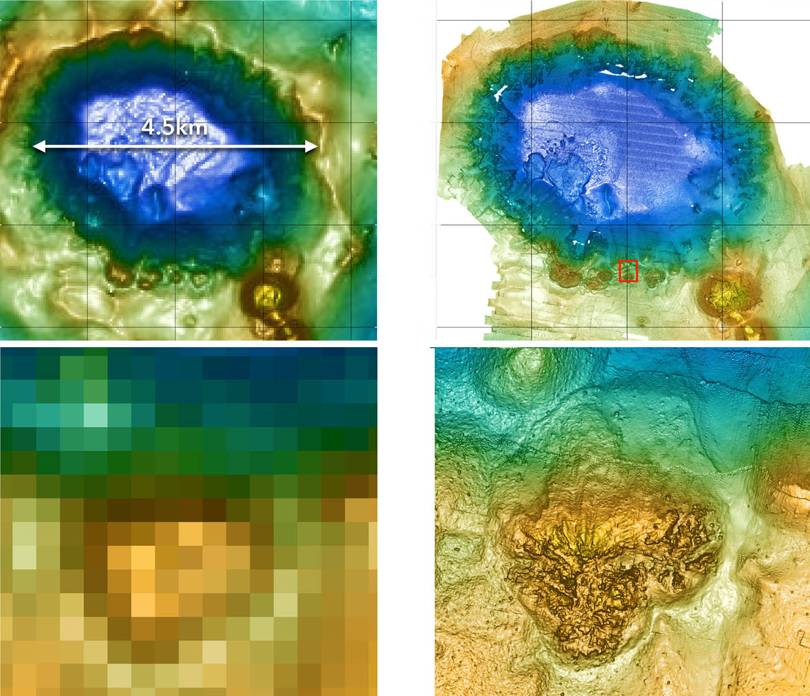

High resolution seafloor map of the Havre undersea volcano caldera with lava that erupted in 2012 lavas shown in red

University of Tasmania, Australia.

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute

Volcanic eruptions on the seafloor are not unusual; around 80 per cent of Earth’s volcanism occurs below the waves.

Detecting them, however, is very tricky indeed.

To notice this type of eruption you need just the right conditions that enabled volcanic rock to accumulate on the sea surface in 2012.

"Being such a unique event, we knew it had the possibility to strongly contribute to the fundamental yet outstanding questions of how submarine volcanism works,” Carey says.

This is why the researchers sent the autonomous vehicle Sentry and the remotely operated vehicle Jason to the depths of the ocean in 2015.

Jason had various sampling equipment on board, to collect rocks or fragmental deposits.

Sentry was key for navigating a steep and rocky ocean floor.

"Sentry can manoeuvre in all directions, whereas other AUVs (Autonomous underwater vehicles) can only go in the forward direction,” Carey says.

Importantly, Sentry provided them with a high resolution map of the seafloor which revealed that underwater volcanoes are as complex as they are on land.

(l-r) Images of ship-based mapping compared with Sentry mapping

University of Tasmania, Australia

"What is really interesting in that the lava flows look exactly like how they would if they were on land,” Carey says.

The discovery also opens up further research into how marine life copes with a gigantic volcanic eruption.

"Havre's eruption produced a blanket of fragmental pumice and ash.

That ash blanket has destroyed most of the life on the volcano," Carey says.

"There were some species recolonising the volcano after just 3 years… the biologists are very interested in what species they are and whether they are local recruits or exotic species."

Links :

- WHOI : a close-up look at a rare underwater eruption

- ScienceAlert : We All Nearly Missed The Largest Underwater Volcano Eruption Ever Recorded

- NASA : NASA satellites pinpoint volcanic eruption (2012) / High-resolution view of Havre Seamount Pumice

- Wired : Havre seamount, the source of Kermadec island pumice raft ? (2012) / New volcanic cone confirms the Havre seamount eruption

- Smithsonian : Havre seamount

- GeoGarage blog : Mysterious pumice raft in Pacific explained /How a fake island landed on Google Earth / New map reveals New Zealand's seafloor in ... / Sophisticated unmanned submarines investigate ... / Kiwi scientists uncover stunning underwater insights / Origin of seabed more complex than scientists first ... / Scientists to survey uncharted seafloor area / New volcanic island unveils explosive past / Nereus deep sea sub 'implodes' 10km-down

No comments:

Post a Comment