Vaan Island in India’s Gulf of Mannar

From BBC by Kamala Thiagarajan

Vaan Island in India’s Gulf of Mannar has been rapidly disappearing into the Laccadive Sea.

But a team of marine biologists is working to save it.

Hundreds of fishing boats bob on the bright blue waters surrounding Vaan Island, a tiny strip of land between India and Sri Lanka.

The island marks the beginning of a fiercely protected fragile zone, the Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve.

These waters are home to India’s most varied and biodiverse coastlines.

Teeming with marine life, it is home to 23% of India’s 2,200 fin fish species, 106 species of crab and more than 400 species of molluscs, as well as the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin, the finless porpoise and the humpback whale.

Vaan Island in India’s Gulf of Mannar (NGA nautical chart) with the GeoGarage platform

Nearly 150,000 fishermen depend on the marine reserve for their livelihoods.

And Vaan Island is the gateway to this world.

Half an hour by boat from the mainland and easily accessible to the 47 villages that are the backbone of this heavily populated coastline, Vaan has always been a refuge from storms for fishermen and a hotspot for researchers.

But for the past 50 years it has been rapidly shrinking.

Hundreds of fishing boats bob on the bright blue waters surrounding Vaan Island, a tiny strip of land between India and Sri Lanka.

The island marks the beginning of a fiercely protected fragile zone, the Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve.

These waters are home to India’s most varied and biodiverse coastlines.

Teeming with marine life, it is home to 23% of India’s 2,200 fin fish species, 106 species of crab and more than 400 species of molluscs, as well as the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin, the finless porpoise and the humpback whale.

Nearly 150,000 fishermen depend on the marine reserve for their livelihoods.

And Vaan Island is the gateway to this world.

Half an hour by boat from the mainland and easily accessible to the 47 villages that are the backbone of this heavily populated coastline, Vaan has always been a refuge from storms for fishermen and a hotspot for researchers.

But for the past 50 years it has been rapidly shrinking.

In 1986, 21 such islands in this region were protected when the Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve, the first of its kind in Asia, was established in the Laccadive Sea.

Now there are only 19.

Two have been submerged and Vaan Island is the next at risk of vanishing.

In 1973, Vaan was 26.5 hectares (65 acres), shrinking to just 4.1 hectares (10 acres) in 2016.

At that point the erosion was so extreme that researchers estimated that it would be entirely underwater by 2022.

Fishing is a crucial source of income in the coastal towns and villages of Tamil Nadu state in southern India

(Credit: Getty Images)

The reason that small, ecologically rich islands like Vaan are vanishing is a combination of unsustainable fishing practices, rising sea levels due to climate change and historic coral mining, which has now been banned in the area.

Artificial reefs were deployed to help buffer waves reaching the islands, and they were effective.

But to give Vaan and its neighbours a longer-term future, the ecosystem as a whole needed replenishing.

Gilbert Mathews, a marine biologist at the Suganthi Devadason Marine Research Institute (SDMRI) in the nearby coastal town of Thuthukudi in southern India, turned to seagrass, a plain and innocuous-looking type of marine plant, as a way to save the island ecosystem.

Often mistaken for seaweed, seagrasses are plants that grow underwater and have well-defined roots, stems and leaves.

They produce flowers, fruits and seeds, and play a vital role in maintaining a marine ecosystem.

“Like corals, these tufts of grass provide a habitat to many splendorous sea-creatures, such as seahorses and lizard fish, which can be found in seagrass throughout the year,” says Mathews.

Seagrass provides the right environment for young fish and invertebrates to conceal themselves, while absorbing dissolved carbon dioxide and creating an oxygen and nutrient-rich environment.

With its ability to trap sediments, seagrass also acts as a natural filter, clearing the waters and slowing erosion.

Mathews first surveyed the seagrass around Vaan Island in 2008, diving into the shallow waters twice a month, for up to eight hours a day.

With a sense of dismay, he saw many tufts of seagrass floating in the water around him.

These islands were home to the most luxuriant seagrass meadows of the Indian sub-continent, but they were coming loose.

When researchers first investigated the seabed around Vaan Island, they found its sea meadows to be in a poor state

(Credit: SDMRI)

The sprigs had been pulled out by fisherman operating trawler boats, who rig two or more nets to scour the shallow waters.

Fishing along shallow waters and the disruption of seagrass beds is illegal in India, but because of poor monitoring, the law is not strictly enforced.

Along with trawlers’ haul of crustaceans and fish, they would pull out hundreds of green sprigs of seagrass that were later discarded in heaps along the shore.

By destroying the seagrass, the trawlermen were inadvertently destabilising the ecosystem on which they relied – without seagrass as the base of the ecosystem, fish stocks dwindled.

In studies between 2011 and 2016, Mathews found that 45 sq km (17 sq miles) of seagrass cover had been degraded in the Palk Bay, where the waters of the Indian Ocean meet the Bay of Bengal.

In the Gulf of Mannar, 24 sq km (9 sq miles) had died.

“We believed that by restoring the seagrass meadows along these waters, we could strengthen the island and possibly save this and prevent others from submerging into the sea,” he says.

Mathews knew that restoring seagrass would be a challenge.

A global assessment of 215 studies, led by marine biologist Michelle Waycott of the University of Adelaide, Australia, found that seagrass had been rapidly disappearing all over the globe.

Meadows spread over an area of 110 sq km (42 sq miles) – equivalent to an area the size of the Indian city of Chandigarh – have been vanishing every year since 1980.

Overall, 29% of seagrass has been lost since records began in 1879.

The seagrass around Vaan Island was patchy and brown before the transplants took place

(Credit: SDMRI)

But if the seagrass meadows could be reinvigorated around Vaan Island, they could also act as a carbon sink.

“Plantation and restoration provide a growing solution towards mitigating climate change and affording some protection in this very fragile part of the world, which is often shaken by hurricanes and strong winds,” says Edward J.K.

Patterson, director of the SDMRI.

At first, the researchers tried pulling up tufts directly from the sandy bottom of the seabed, and moving them to sites that had been badly depleted.

But it didn’t work – the trawlers still pulled them out, undoing their painstaking work.

It became evident that the team needed to find another way, but most of the usual rehabilitation techniques used in other parts of the world were expensive, even more labour-intensive and therefore not viable.

For instance, one well-known method was the dispersal and sowing of seagrass seeds.

But this wasn’t practical: the beds had to be dug out underwater and each seed planted by hand.

Mathews and his colleagues spent the next eight years trying to work out a better way to save the seagrass.

Meanwhile, the erosion continued and in 2013 Vaan Island split in two as the sea encroached.

In 2016, the Gulf of Mannar experienced its worst ever coral bleaching episode, losing 16% of its coral cover.

Restoring corals and seagrass were twin projects, as both corals and seagrass act as natural barriers, affording some protection from strong waves and reducing erosion.

The marine biologists brought hefty sacks of fresh seagrass to the surface for transplantation to weaker spots

(Credit: SDMRI)

Scientists from the SDMRI had by then perfected a better transplantation technique for restoring seagrass.

Mahalakshmi Bupathy, a researcher specialising in soft corals, joined the team in 2016 along with her “diving buddy”, coral sponge scholar Arathy Ashok, to try out this new method.

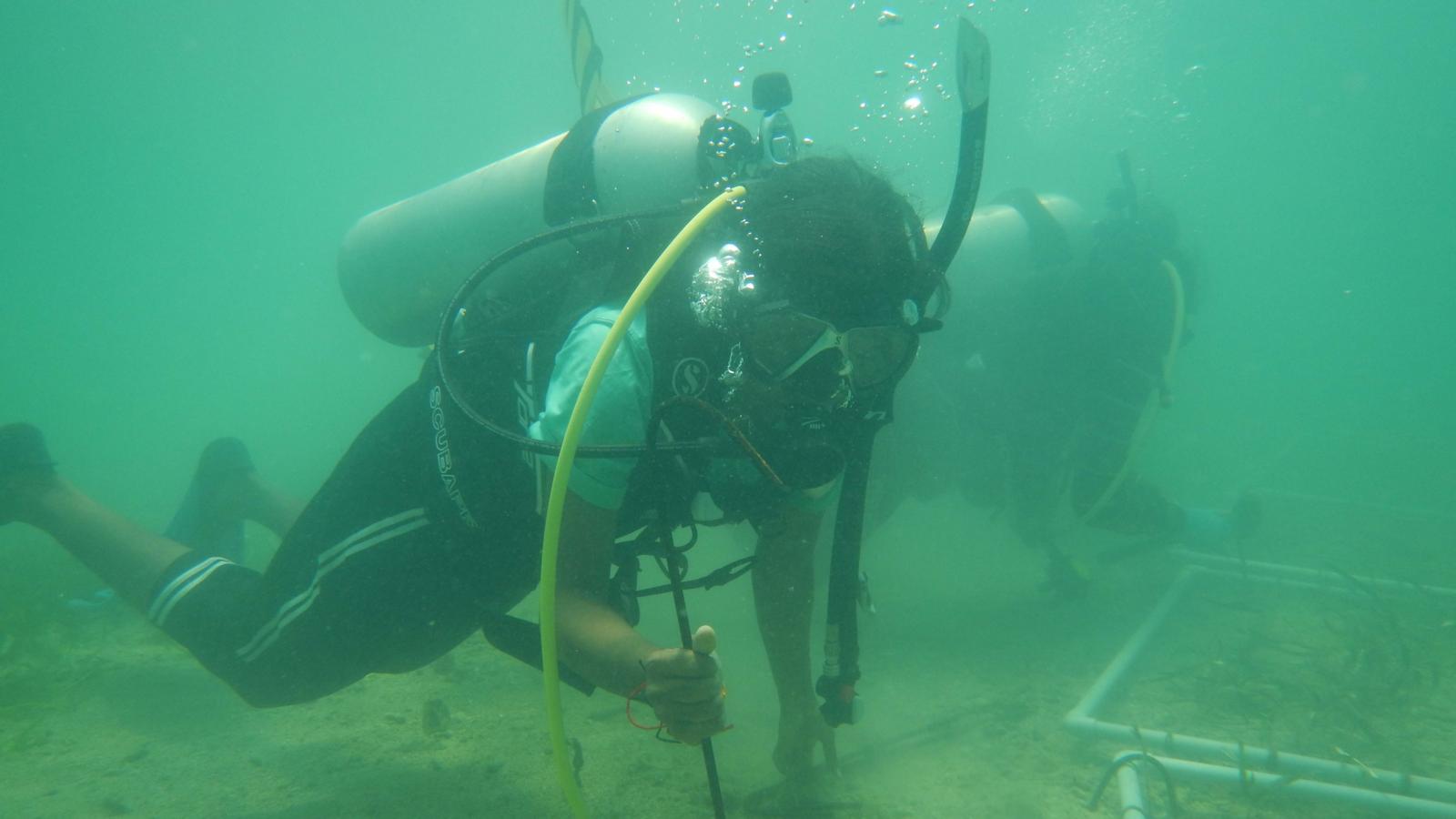

Several times a month, Bupathy and Ashok’s day began at 5am with a dive down to the seabed.

First, they surveyed the sites along the 19 remaining islands of the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Straight and noted which underwater areas needed more seagrass and which harboured luxuriant growth.

The latter could be promising “donors” to replenish the weaker sites.

They also took stock of the area’s biodiversity, recording the vegetation and the fish population.

Where there was plenty of seagrass, the ocean life was surprisingly rich.

“I found giant barrel sponges that had been last sighted in these waters 30 years ago,” says Ashok.

“These are such enigmatic creatures.”

Next, the pair collected mature seagrass sprigs from chosen donor sites.

“One had to be particularly careful while digging them out,” says Bupathy.

The sprigs have two kinds of roots – one set that grew vertically and other horizontally, which needed to be teased out without damaging them.

Before dropping the sprigs into the bags, Bupathy and Ashok washed them thoroughly in seawater to clear away any sediment.

The initial unsuccessful attempts had revealed that replanting with excessive sediment blocked the sunlight and prevented photosynthesis, stunting the sprigs’ growth.

The team then put the bags on the boats where the other team members were waiting with containers filled with seawater.

Immersed in these containers, the seagrass then had to be transported to the transplant sites within an hour, or the sprigs would die.

The scientists had a short window to sort the delicate seagrass before transplanting it to its new home (Credit: SDMRI)

When they reached their target – barren areas of former meadows – the shoots were then tied to a 1 sq m (11 sq ft) plastic quadrat using jute twine.

A total of six pieces of twine could bind nearly 120 shoots to the squares.

The roots had to be left intact, so that they could embed in the soil when the transplant took place.

Depending on weather conditions, the team fixed up to 80 quadrats a day, each bound with the shoots that might, if they were lucky, hold Vaan Island together.

“It took two to three months for the roots to bind to the sandy and muddy underwater terrain,” says Ashok.

Once it had, they would dive back to retrieve the plastic quadrats.

They monitored the rehabilitated sites closely to see whether the seagrass was taking hold.

Every month the team measured environmental parameters that could affect seagrass growth, such as water temperature, salinity, acidity, turbulence, sedimentation and dissolved oxygen levels.

By the fifth month, the team began to see signs of success – it seemed the island’s seagrass was growing back.

The quadrats had given the sprigs the extra stability they needed to take root.

“We could visibly see an increase in biodiversity in these areas,” says Bupathy.

“We saw a great variety of fin fish, molluscs, horse fish, sea turtles.”

The seagrass meadows that had acted as donors had replenished the lost stock too and were as dense as ever.

The degraded seagrass meadows recovered with the help of the targeted transplant process, and the donor areas replenished their lost stock too

(Credit: SDMRI)

But, as fish and other marine life began to return, so too did the fishermen.

Nets from bottom-trawlers began to pull up the newly transplanted seagrass.

The team kept diving, reaffixing the shoots when they were pulled up.

Rough weather between April and September often impeded their work, but in the eight months when the seas were calm, the restoration project made steady progress.

The race against the trawlers often meant long hours underwater, with quick meals on boats.

Bupathy remembers one occasion when her nose started to bleed after she had dived despite having a cold.

Ashok recalls the small scratches and bruises from corals she brushed past.

Seeing the seagrass beds grow and thrive, however, made up for any discomfort.

“Watching the ecosystem take shape and grow diverse was very rewarding,” Bupathy says.

There was another reason besides preventing the erosion of Vaan Island that encouraged the researchers’ dogged persistence.

Losing seagrass meadows is akin to mass deforestation on land, and it can have a domino effect because seagrass is sensitive to changes in temperature.

“Rapid ocean warming in the recent decades have shrunk carbon-storing seagrass meadows, which in turn accelerates global warming,” says Roxy Mathew Koll, a climate change scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology in Pune.

All of which makes the efforts of Bupathy, Ashok and their colleagues more timely.

“The restoration of seagrass meadows along the Indian coast can help in saving the ecosystem,” says Koll.

“India has a large coastline, so if this is successful, it can be replicated for other similar environments along the coast – this will contribute to national effort to mitigate emissions and as much as possible, to reverse climate change.”

When the seagrass is restored, it is hoped that species such as the dugong will thrive again in the Gulf of Mannar, where it is currently under threat

(Credit: Getty Images)

In the long run, enforcing India’s laws against disturbing seagrass will have to be part of the solution.

In 2019, a marine fisheries regulation management bill was proposed.

If it is passed into law, larger fishing vessels and mechanised trawlers would need to be registered and licensed under state departments.

They would need a permit to fish, which could lead to better monitoring and ultimately less destruction of the region’s seagrass and corals.

To date, the joint efforts to restore the coral and seagrass around Vaan Island and its neighbours has strengthened the degraded shoreline, making it less vulnerable to threats, says Patterson.

“This is the first attempt in India to fight to save a sinking island,” he says.

And it appears to be working – for now, Vaan island is stable.

--

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 0kg CO2: the writer interviewed sources remotely, being familiar with the Gulf of Mannar area and having worked there several times in the past.

The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view.

Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

So far, nine acres of degraded seagrass have been rehabilitated in the Gulf of Mannar.

As well as at Vaan Island, other fast-eroding spots such as Koswari Island, Kariyachalli island and Vilanguchali have had successful transplants.

Two further acres have been restored around islands in Palk Bay.

The researchers are hoping that in time the restored seagrass will woo back endangered mammals like the dugong.

No comments:

Post a Comment