View

of the bow of the RMS Titanic photographed in June 2004 by the ROV

Hercules during an expedition returning to the shipwreck of the Titanic.

(Courtesy of NOAA/Institute for Exploration/University of Rhode Island)

From Hydro by Albert E. Theberge Understanding the Unthinkable In the night of 14 April 1912, the unthinkable happened.

The mightiest ship afloat, the brand new White Star Line ship Titanic, was on its maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York.

The ship was advertised as unsinkable.

And, if unsinkable, why should there be adequate lifeboats for all of the passengers and crew? The ship departed from Southampton on 10 April.

Less than five days later, it was at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.

More than 1,500 people perished within three hours of striking an iceberg, which ripped the bottom out of the ship.

How this happened is a story told many times.

Human hubris, unswerving trust in the infallibility of technology, and the commercial impetus of fast Atlantic passages all contributed to the loss of the ship and the accompanying loss of life.

Even as the ship was settling in the waters of an icy North Atlantic, some survivors reported that there was a belief among many passengers that the ship was the safer place to be; accordingly, not all the lifeboats were filled to capacity.

This accident shocked the international community.

The British and American governments investigated the accident – the British determined: “That the loss of said ship was due to collision with an iceberg, brought about by the excessive speed at which the ship was being navigated.” Certainly, that was the major factor.

However, like many accidents, there were a number of contributing causes.

These included: watertight bulkheads that were improperly designed; an insufficient number of lifeboats and life rafts; apparent lack of concern by the captain concerning reports of ice prior to collision with the iceberg; little training of crew in emergency procedures including lowering of lifeboats; no radio watches on nearby ships which could have assisted in lifesaving efforts; and, remarkably, not even binoculars for the ship’s lookouts.

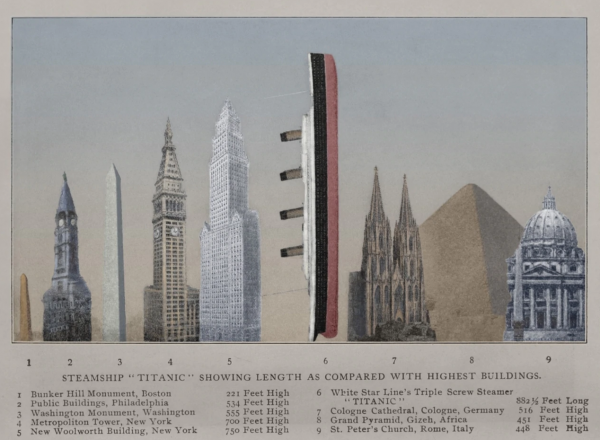

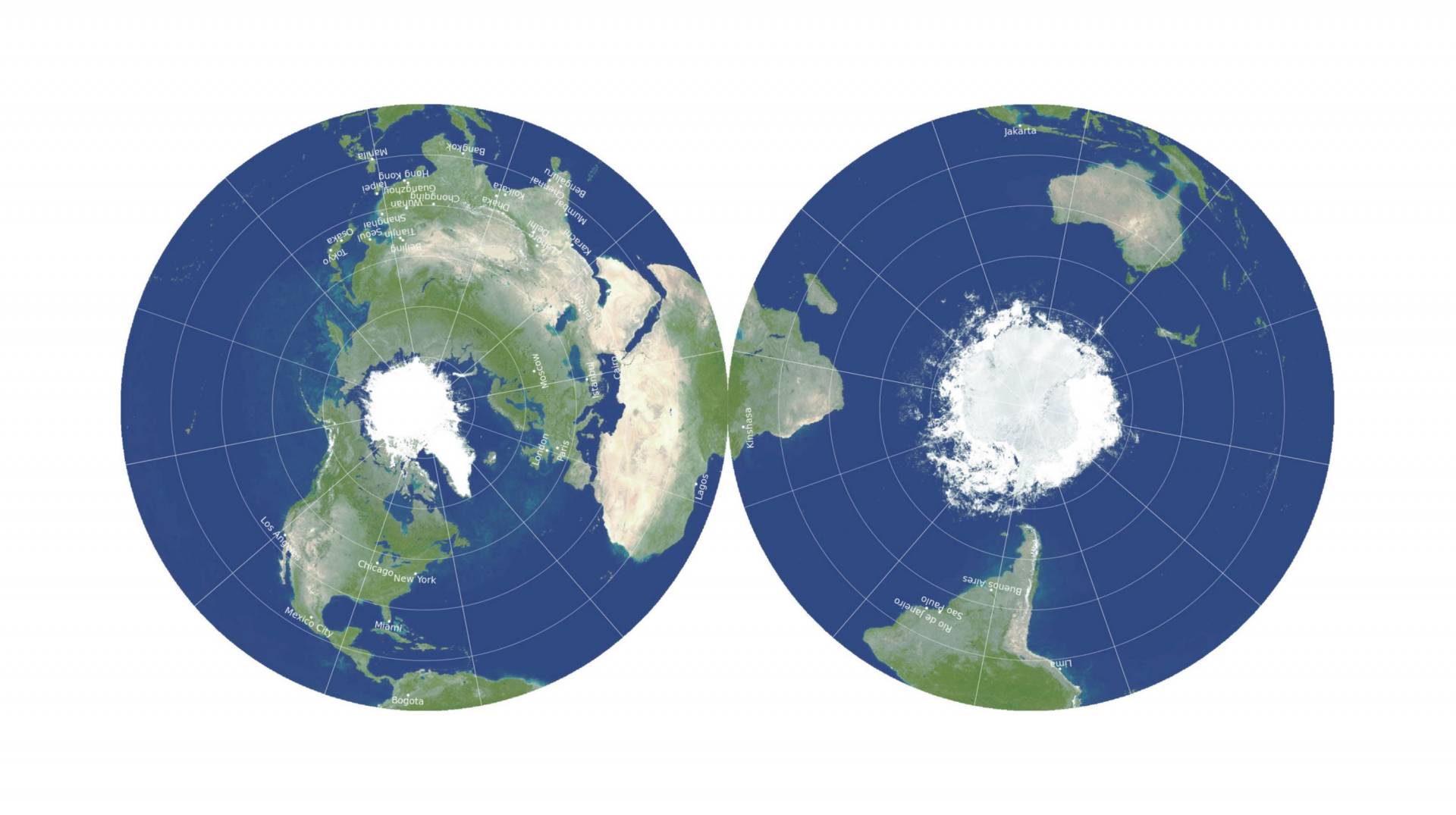

Steamship Titanic showing length as compared with highest buildings.

Steamship Titanic showing length as compared with highest buildings.

Both the British and American governments arrived at similar conclusions and recommendations following the loss of the Titanic.

The chief recommendation was that all ships be equipped with sufficient lifeboats for passengers and crew, that all ocean-going ships maintain 24-hour radio-telegraph watches, and that bulkheads be designed such that flooding of any two adjacent compartments would not result in sinking of a vessel.

These recommendations and others were adopted by the first International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) at a conference held in London in 1914.

Development of Seafloor Mapping Technologies

Commercial concerns saw an opportunity in the Titanic disaster and began searching for a means to determine the presence of icebergs and other unseen or submerged obstructions forward of moving vessels.

European and North American inventors joined the race.

In 1912, Reginald Fessenden, a Canadian inventor and radio pioneer, joined Submarine Signal Company, a forerunner of today’s Raytheon, and began work on an electro-acoustic oscillator similar to a modern transducer.

This oscillator was originally designed for both ship-to-ship communication and to receive reflected sound from an underwater object.

In late April 1914, Fessenden tested this device off the Grand Banks on the US Revenue Cutter Miami and succeeded in reflecting sound off an iceberg at a range of approximately two miles and hearing the return echo.

A second echo was heard that was determined to be from the bottom.

Submarine warfare during World War I accelerated research into the field of acoustics.

By the end of the war, the use of acoustics for both detection of objects in the water and measuring depth had been proven.

In 1922, the USS Stewart, equipped with a Hayes Sonic Depth Finder that utilized a Fessenden oscillator, ran a line of soundings across the Atlantic Ocean taking over 900 individual soundings.

The profile obtained from these soundings was published in the first issue of the International Hydrographic Review.

Piano-wire sounding systems became obsolete overnight.

Although leadline sounding continued for a number of years in shallow water, acoustic sounding systems replaced the leadline for most purposes within two decades.

World War II further accelerated the development of directional sonar systems (called Asdic in England).

Although meant originally for detection of submarines, these systems ultimately developed into modern side-scan sonar systems.

Underwater photography equipment and magnetic anomaly detection (MAD) instruments were in their infancy during this period.

MAD systems were proved effective in detecting submarines.

An early use by hydrographers of the complementary use of sonar, underwater photography and MAD gear was in the charting of ships torpedoed off the United States East Coast.

This was done by Coast and Geodetic Survey (C&GS) officers working off the Coast Guard buoy tender Gentian in 1944.

Following the war, there were further advances, including the development of an early side-scan sonar system called Shadowgraph in 1954 by German scientist Julius Hagemann, who was working at the United States Navy Mine Defense Laboratory.

This system remained classified for many years, but civil use of side-scan began developing shortly after this advance.

In the commercial sector, Harold Edgerton of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Martin Klein, also of MIT, were early pioneers.

Edgerton turned a bottom-penetration sonar on its side in 1963 and imaged a sunken lightship from a C&GS vessel.

Edgerton was a founder of EG&G and discovered the Civil War era USS Monitor off Cape Hatteras with an EG&G commercial side-scan system.

Martin Klein began his career with EG&G but left to found Klein Associates, a name synonymous with side-scan technology.

Advances in depth measurement technology paralleled the development of side-scan technology.

In April 1961, engineers at General Instruments Corporation developed a proposal for BOMAS, Bottom Mapping Sonar.

Quoting from the proposal: “BOMAS derives bottom profile information from the intersection of the ocean bottom with a vertical plane perpendicular to the heading of a ship.

The sonar data is processed automatically and in real time to provide a depth contour strip map….

A sonar intensity map can be provided simultaneously….”

Multi-beam sounding with its attendant bottom reflectivity mapping capability was born.

Two years later, the first prototype multi-beam system was installed on the USS Compass Island and subsequent units installed on Navy survey ships.

In the meantime, the acronym had changed to SASS (Sonar Array Sounding System).

By the late 1970s, the technology had migrated to the civil community and has since displaced single beam sounding systems as the standard seafloor mapping tool.

Painting of the Titanic sinking by the bow, with people rowing a lifeboat in the foreground and other people in the water.

Icebergs are visible in the background.

(Engraving by Willy Stöwer: Der Untergang der Titanic)

Finding Titanic and the Aftermath of the Discovery

In the immediate aftermath of the sinking, proposals to locate the sunken Titanic were discussed and ultimately dismissed because the wreck lay well beyond the limits of technology at that time.

Through the decades, the development of subsea technology finally provided the means to locate the wreck and subsequently to not only investigate it using remote technology, but also to dive to the wreck and conduct a series of investigations that included surveys of the interior of the ship.

In July 1985, the final search began, with Ifremer deploying their newly developed side-scan sonar SAR vehicle on a mission led by Jean-Louis Michel on the research vessel Le Suroit.

That survey covered 70% of a 150 square nautical mile survey box without locating the Titanic.

Picking up the search in August, the WHOI team, led by Robert Ballard aboard the research vessel Knorr, utilized the towed vehicle Argo, with a 100kHz side-scan sonar, and three low-light black and white video cameras.

Ballard’s team relied on the optical system to locate the Titanic, and in the early morning hours of 1 September, the unmistakable form of a boiler made it clear that the search was over.

Titanic’s final resting place had been found.

Since the discovery in 1985, a series of expeditions have visited the Titanic with a variety of goals.

Ballard and Woods Hole returned to the wreck in July 1986 on the WHOI research vessel Atlantis II, with the submersible Alvin, and the ROV Jason Jr.

The 1986 expedition photographed and filmed the wreck, focusing on the largely intact bow section.

Working from the data collected from the 1985 Argo survey as well as 1986 data, WHOI’s William Lange and others assembled a preliminary site map of the Titanic wreck site that delineated the site from the bow to the stern section and plotted a wide range of features scattered on the seabed.

A private venture funded and led by RMS Titanic, Inc., the salvor-in-possession of the wreck (RMST), and technically supported by Ifremer, returned to the wreck in July 1987 and made 32 dives to recover some 1,800 artifacts from the seabed, the first of a series of recovery dives made by RMST until 2004, which ultimately salvaged nearly 5,000 artifacts.

The remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Hercules exploring the bow of the Titanic, 2004.

(Courtesy: Institute for Exploration/University of Rhode Island/NOAA

Dives made by documentary film crews and James Cameron (whose first dives were in 1995) working with the P.P.

Shirsov Institute, captured dramatic images of the wreck as well as additional technical information and a more detailed view of aspects of the wreck site in the Mir submersibles.

In particular, Cameron’s extensive documentation and penetration of the interior of the bow with small ROVs known as ‘bots’ provided incredible insights into the ongoing processes of environmental change and preservation inside the ship, as well as evidence of what had occurred during the sinking of the Titanic.

Cameron’s work has arguably done more to share the Titanic as a wreck site with a greater audience than anyone else.

The scientific products of the various expeditions include a detailed analysis of the microbiological corrosion of the ship’s steel (led by Roy Cullimore), geological studies of the sediments and current studies (by the Shirsov Institute), a detailed sonar survey of the bow where the Titanic struck the iceberg, photo mosaics of the bow section, and forensic studies of the ship’s sinking sequence and break-up.

In addition, RMS Titanic, Inc. commissioned the creation of an ‘archaeological GIS’ map delineating where the 5,000 artifacts had been recovered from between 1987 and 2004.

That GIS, which is being completed by RMST under contract by the Center for Maritime & Underwater Resource Management of Michigan, a private non-profit, is reported to be nearly complete.

The National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration’s Office of Ocean Exploration conducted two missions to the Titanic in 2003 and 2004.

As the nation’s ocean agency, NOAA has an interest in the scientific and cultural aspects of the Titanic.

NOAA’s focus is to build a baseline of scientific information from which we can measure the processes and deterioration of the Titanic, and apply that knowledge to many other deepwater shipwrecks and submerged cultural resources.

The 2003 mission, with the Shirsov Institute, had several key goals, the first being to catalogue any anthropogenic activities currently impacting the wreck site, or evidence of such activity since its discovery in 1985.

Digital imagery was obtained and a deck-view mosaic of the bow section was created.

Additionally, ongoing bacteriological analysis was conducted as well as basic oceanographic research.

The 2004 Mission, Conducted On Board the NOAA Research Vessel

Ronald H. Brown, working with Robert Ballard, then (and now) with the University of Rhode Island and the Institute of Archaeological Oceanography, utilized an ROV to continue the assessment of the wreck’s ongoing environmental changes and the bacteriological work of Roy Cullimore.

One other key achievement of the 2004 mission was the completion of a topographic map of Titanic Canyon and the surrounding area, including the wreck of the Titanic, with a Seabeam 2112 multi-beam sonar system.

The digital terrain model of this large area of seabed places the Titanic within a larger geological and geographical context.

NOAA also participated, as did Woods Hole, the National Park Service, the Institute of Nautical Archaeology, the Waitt Institute and contracted partners such as Phoenix International, Ltd., in RMS Titanic, Inc.’s last (to date) expedition to the wreck in August 2010.

This mission, with a non-recovery scientific focus, focused on William Lange’s and the WHOI Advanced Imaging and Visualization Laboratory’s work to create a detailed 2D and 3D visual mosaic of the site.

To do so, it made a detailed survey using the Waitt Institute’s REMUS 6000 autonomous underwater vehicles of an approximately ten square nautical mile survey zone around the wreck site, with a series of closer, higher resolution surveys of the area delineated in the 1986 WHOI map of the site and even closer surveys of key features and areas of the site.

That project was successful in generating the mapping data as well as comprehensive visual coverage of the wreck, including detailed photo mosaics of a number of features in the artifact scatter, which included sections of the ship’s hull, machinery and equipment and other artifacts.

This composite image, released by RMS Titanic Inc., and made from sonar and more than 100,000 photos taken in 2010 by unmanned, underwater robots, shows a small portion of a comprehensive map of the 3-by-5-mile debris field surrounding the bow of the Titanic on the bottom of the North Atlantic Ocean (Courtesy: AP Photo/RMS Titanic Inc.)

What is clear in this brief overview is that the last few decades have witnessed a revolutionary expansion of humanity’s capacity to not only locate deep-sea shipwrecks, but increasingly to capture imagery and data that essentially ‘virtually raises’ these wrecks for ongoing research as well as public education.

In many ways, the Titanic and the surrounding area are likely to be the best-studied section of the deep ocean floor.

That status has come because of the iconic nature of the wreck and the potential for profit from the opportunity to connect to this ship and its tragic loss either through a tour of the recovered artifacts or a virtual tour on film or in a photograph.

At the same time, measurable and important science has been conducted, and in that, a way forward for not only this site but others has been demonstrated, especially in the adaptation and adoption of technology to access and learn from sites once thought unreachable.

Links :

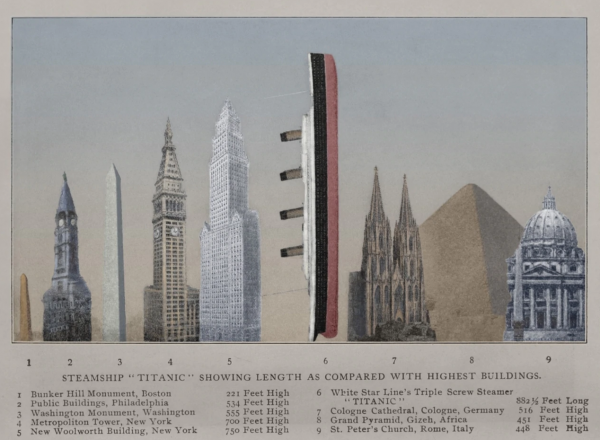

North Rift crack photographed by Halley team in January 2021

North Rift crack photographed by Halley team in January 2021 Map of Brunt ice shelf and Halley Research Station

Map of Brunt ice shelf and Halley Research Station