A new MIT study finds that over the coming decades climate change will affect the ocean’s color, intensifying its blue regions and its green ones.

Image: NASA Earth Observatory

From MIT news by Jennifer Chu

Climate-driven changes in phytoplankton communities will intensify the blue and green regions of the world’s oceans.

Climate change is causing significant changes to phytoplankton in the world’s oceans, and a new MIT study finds that over the coming decades these changes will affect the ocean’s color, intensifying its blue regions and its green ones.

Satellites should detect these changes in hue, providing early warning of wide-scale changes to marine ecosystems.

Writing in Nature Communications, researchers report that they have developed a global model that simulates the growth and interaction of different species of phytoplankton, or algae, and how the mix of species in various locations will change as temperatures rise around the world.

The researchers also simulated the way phytoplankton absorb and reflect light, and how the ocean’s color changes as global warming affects the makeup of phytoplankton communities.

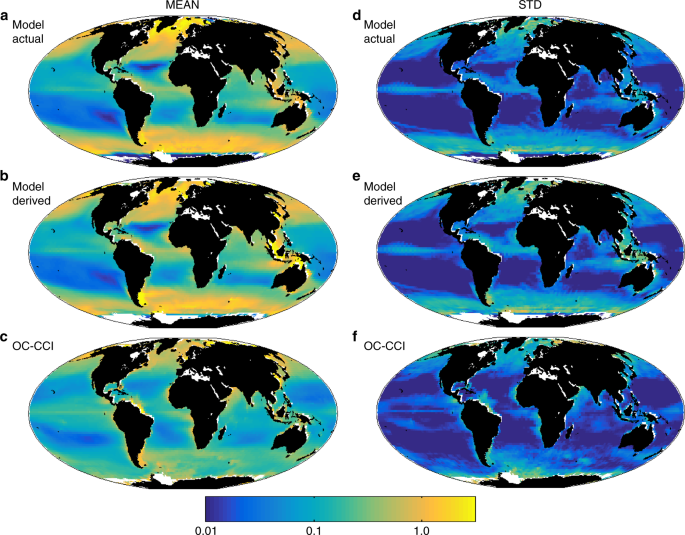

Current day Chl-a and its interannual variability.

Composite mean Chl-a (mg Chl m−3) for 1998–2015:

a model actual;

b model satellite-like derived (using an algorithm and the model RRS,);

c Ocean Colour Climate Change Initiative project (OC-CCI, v2) satellite derived. Interannual variability defined as the standard deviation of the annual mean composites (1998–2015):

d model actual;

e model satellite-like derived; f OC-CCI, v2 satellite derived. White areas are regions where model resolution is too coarse to capture the smaller seas, or where there is persistent ice cover.

Model actual Chl-a is the sum of the dynamic Chl-a for each phytoplankton type that is explicitly resolved in the model.

It is equivalent to the Chl-a that would be measured in situ.

This is distinct to satellite-derived Chl-a which is calculated via an algorithm derived from the reflected light measured by ocean colour satellite instruments

The researchers ran the model through the end of the 21st century and found that, by the year 2100, more than 50 percent of the world’s oceans will shift in color, due to climate change.

The study suggests that blue regions, such as the subtropics, will become even more blue, reflecting even less phytoplankton — and life in general — in those waters, compared with today.

Some regions that are greener today, such as near the poles, may turn even deeper green, as warmer temperatures brew up larger blooms of more diverse phytoplankton.

“The model suggests the changes won’t appear huge to the naked eye, and the ocean will still look like it has blue regions in the subtropics and greener regions near the equator and poles,” says lead author Stephanie Dutkiewicz, a principal research scientist at MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences and the Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change.

“That basic pattern will still be there. But it’ll be enough different that it will affect the rest of the food web that phytoplankton supports.”

Dutkiewicz’s co-authors include Oliver Jahn of MIT, Anna Hickman of the University of Southhampton, Stephanie Henson of the National Oceanography Centre Southampton, Claudie Beaulieu of the University of California at Santa Cruz, and Erwan Monier, former principal research scientist at the MIT Center for Global Change Science, and currently assistant professor at the University of California at Davis, in the Department of Land, Air and Water Resources.

This research was supported, in part, by NASA and the Department of Energy.

The story of oceans and climate would not be complete until we explore the impact of weather and climate on marine life.

We also need to understand how ocean life, notably phytoplankton might modulate oceanic weather and climate, through their role in the global carbon cycle, and on the ocean heat budget. One way that phytoplankton influence the oceans is through heating.

Photosynthesis is quite inefficient, so much of the light absorbed by phytoplankton cells is released as heat.

Chlorophyll count

The ocean’s color depends on how sunlight interacts with whatever is in the water.

Water molecules alone absorb almost all sunlight except for the blue part of the spectrum, which is reflected back out.

Hence, relatively barren open-ocean regions appear as deep blue from space.

If there are any organisms in the ocean, they can absorb and reflect different wavelengths of light, depending on their individual properties.

Phytoplankton, for instance, contain chlorophyll, a pigment which absorbs mostly in the blue portions of sunlight to produce carbon for photosynthesis, and less in the green portions.

As a result, more green light is reflected back out of the ocean, giving algae-rich regions a greenish hue.

Since the late 1990s, satellites have taken continuous measurements of the ocean’s color.

Scientists have used these measurements to derive the amount of chlorophyll, and by extension, phytoplankton, in a given ocean region.

But Dutkiewicz says chlorophyll doesn’t necessarily reflect the sensitive signal of climate change.

Any significant swings in chlorophyll could very well be due to global warming, but they could also be due to “natural variability” — normal, periodic upticks in chlorophyll due to natural, weather-related phenomena.

“An El Niño or La Niña event will throw up a very large change in chlorophyll because it’s changing the amount of nutrients that are coming into the system,” Dutkiewicz says.

“Because of these big, natural changes that happen every few years, it’s hard to see if things are changing due to climate change, if you’re just looking at chlorophyll.”

In this extra video, Dr Michelle Gierach from NASA JPL outlines how models can be used to assess phytoplankton biodiversity, and how future satellite missions will lead to better monitoring of coral health, biodiversity and potentially even phytoplankton species.

Modeling ocean light

Instead of looking to derived estimates of chlorophyll, the team wondered whether they could see a clear signal of climate change’s effect on phytoplankton by looking at satellite measurements of reflected light alone.

The group tweaked a computer model that it has used in the past to predict phytoplankton changes with rising temperatures and ocean acidification.

This model takes information about phytoplankton, such as what they consume and how they grow, and incorporates this information into a physical model that simulates the ocean’s currents and mixing.

This time around, the researchers added a new element to the model, that has not been included in other ocean modeling techniques: the ability to estimate the specific wavelengths of light that are absorbed and reflected by the ocean, depending on the amount and type of organisms in a given region.

“Sunlight will come into the ocean, and anything that’s in the ocean will absorb it, like chlorophyll,” Dutkiewicz says.

“Other things will absorb or scatter it, like something with a hard shell. So it’s a complicated process, how light is reflected back out of the ocean to give it its color.”

When the group compared results of their model to actual measurements of reflected light that satellites had taken in the past, they found the two agreed well enough that the model could be used to predict the ocean’s color as environmental conditions change in the future.

“The nice thing about this model is, we can use it as a laboratory, a place where we can experiment, to see how our planet is going to change,” Dutkiewicz says.

Marine diatom cells (Rhizosolenia setigera), which are an important group of phytoplankton.

Photograph: Karl Bruun/AP

A signal in blues and greens

As the researchers cranked up global temperatures in the model, by up to 3 degrees Celsius by 2100 — what most scientists predict will occur under a business-as-usual scenario of relatively no action to reduce greenhouse gases — they found that wavelengths of light in the blue/green waveband responded the fastest.

What’s more, Dutkiewicz observed that this blue/green waveband showed a very clear signal, or shift, due specifically to climate change, taking place much earlier than what scientists have previously found when they looked to chlorophyll, which they projected would exhibit a climate-driven change by 2055.

“Chlorophyll is changing, but you can’t really see it because of its incredible natural variability,” Dutkiewicz says.

“But you can see a significant, climate-related shift in some of these wavebands, in the signal being sent out to the satellites.

So that’s where we should be looking in satellite measurements, for a real signal of change.”

Though plankton can't be seen from space, NASA's SeaWIFS satellite can image the chlorophyll found in phytoplankton.

Since the fall of 1997, NASA satellites have continuously and globally observed all plant life at the surface of the land and ocean.

Satellites measured land and ocean life from space as early as the 1970s.

But it wasn't until the launch of the Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view Sensor (SeaWiFS) in 1997 that the space agency began what is now a continuous, global view of both land and ocean life.

This video was created with data from satellites including SeaWiFS, and instruments including the NASA/NOAA Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite and the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer.

On land, vegetation appears on a scale from brown (low vegetation) to dark green (lots of vegetation); at the ocean surface, phytoplankton are indicated on a scale from purple (low) to yellow (high).

In the Northern Hemisphere, ecosystems wake up in the spring, taking in carbon dioxide and exhaling oxygen as they sprout leaves — and a fleet of Earth-observing satellites tracks the spread of the newly green vegetation.

Meanwhile, in the oceans, microscopic plants drift through the sunlit surface waters and bloom into billions of carbon dioxide-absorbing organisms — and light-detecting instruments on satellites map the swirls of their color.

The space-based view of life allows scientists to monitor crop, forest and fisheries health around the globe.

Observations from space help determine agricultural production globally, and are used in famine early warning detection.

But the space agency's scientists have also discovered long-term changes across continents and ocean basins.

As NASA begins its third decade of global ocean and land measurements, these discoveries point to important questions about how ecosystems will respond to a changing climate and broad-scale changes in human interaction with the land.

The climate is warming fastest in Arctic regions, and the impacts on land are visible from space as well.

The tundra of Western Alaska, Quebec and elsewhere is turning greener as shrubs extend their reach northwards.

And as concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere continue to rise and warm the climate, NASA's global understanding of plant life will play a critical role in monitoring carbon as it moves through the Earth system.

Expanding these observations to the rest of the globe, the scientists could track the impact on plants of rainy and dry seasons in Africa, see the springtime blooms in North America, and the after-effects of wildfires in forests worldwide.

The grasslands of Senegal, for example, undergo drastic seasonal changes.

Grasses and shrubs flourish during the rainy season from June to November, then dry up when the rain stops.

With early weather satellite data in the 1970s and '80s, NASA Goddard scientist Compton Tucker was able to see that greening and die-back from space, measuring the chlorophyll in the plants below.

He developed a way of comparing satellite data from two wavelengths, which gives a quantitative measurement of this greenness called the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index.

But land is only part of the story.

At the base of the ocean’s food web are phytoplankton — tiny organisms that, like land plants, turn water and carbon dioxide into sugar and oxygen, aided by the right combination of nutrients and sunlight.

Recent studies of ocean life have shown that a long-term trend of rising sea surface temperatures is causing ocean regions known as “biological deserts” to expand.

These regions of low phytoplankton growth occur in the center of large, slow-moving currents called gyres.

The next step for NASA scientists is actually looking at the process of photosynthesis from space. When plants undergo that chemical process, some of the absorbed energy fluoresces faintly back, notes Joanna Joiner, a NASA Goddard research scientist.

With satellites that detect signals in the very specific wavelengths of this fluorescence, and a fine-tuned analysis technique that blocks out background signals, Joiner and her colleagues can see where and when plants start converting sunlight into sugars.

Earth is still the only planet we know of with life - the one thing that, so far, makes Earth unique among the thousands of other planets we've discovered.

With that in mind, our habitable home world seems evermore fragile and beautiful when considering the vastness of unlivable space.

Since the fall of 1997, NASA satellites have continuously and globally observed all plant life at the surface of the land and ocean.

Satellites measured land and ocean life from space as early as the 1970s.

But it wasn't until the launch of the Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-view Sensor (SeaWiFS) in 1997 that the space agency began what is now a continuous, global view of both land and ocean life.

This video was created with data from satellites including SeaWiFS, and instruments including the NASA/NOAA Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite and the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer.

On land, vegetation appears on a scale from brown (low vegetation) to dark green (lots of vegetation); at the ocean surface, phytoplankton are indicated on a scale from purple (low) to yellow (high).

In the Northern Hemisphere, ecosystems wake up in the spring, taking in carbon dioxide and exhaling oxygen as they sprout leaves — and a fleet of Earth-observing satellites tracks the spread of the newly green vegetation.

Meanwhile, in the oceans, microscopic plants drift through the sunlit surface waters and bloom into billions of carbon dioxide-absorbing organisms — and light-detecting instruments on satellites map the swirls of their color.

The space-based view of life allows scientists to monitor crop, forest and fisheries health around the globe.

Observations from space help determine agricultural production globally, and are used in famine early warning detection.

But the space agency's scientists have also discovered long-term changes across continents and ocean basins.

As NASA begins its third decade of global ocean and land measurements, these discoveries point to important questions about how ecosystems will respond to a changing climate and broad-scale changes in human interaction with the land.

The climate is warming fastest in Arctic regions, and the impacts on land are visible from space as well.

The tundra of Western Alaska, Quebec and elsewhere is turning greener as shrubs extend their reach northwards.

And as concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere continue to rise and warm the climate, NASA's global understanding of plant life will play a critical role in monitoring carbon as it moves through the Earth system.

Expanding these observations to the rest of the globe, the scientists could track the impact on plants of rainy and dry seasons in Africa, see the springtime blooms in North America, and the after-effects of wildfires in forests worldwide.

The grasslands of Senegal, for example, undergo drastic seasonal changes.

Grasses and shrubs flourish during the rainy season from June to November, then dry up when the rain stops.

With early weather satellite data in the 1970s and '80s, NASA Goddard scientist Compton Tucker was able to see that greening and die-back from space, measuring the chlorophyll in the plants below.

He developed a way of comparing satellite data from two wavelengths, which gives a quantitative measurement of this greenness called the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index.

But land is only part of the story.

At the base of the ocean’s food web are phytoplankton — tiny organisms that, like land plants, turn water and carbon dioxide into sugar and oxygen, aided by the right combination of nutrients and sunlight.

Recent studies of ocean life have shown that a long-term trend of rising sea surface temperatures is causing ocean regions known as “biological deserts” to expand.

These regions of low phytoplankton growth occur in the center of large, slow-moving currents called gyres.

The next step for NASA scientists is actually looking at the process of photosynthesis from space. When plants undergo that chemical process, some of the absorbed energy fluoresces faintly back, notes Joanna Joiner, a NASA Goddard research scientist.

With satellites that detect signals in the very specific wavelengths of this fluorescence, and a fine-tuned analysis technique that blocks out background signals, Joiner and her colleagues can see where and when plants start converting sunlight into sugars.

Earth is still the only planet we know of with life - the one thing that, so far, makes Earth unique among the thousands of other planets we've discovered.

With that in mind, our habitable home world seems evermore fragile and beautiful when considering the vastness of unlivable space.

According to their model, climate change is already changing the makeup of phytoplankton, and by extension, the color of the oceans.

By the end of the century, our blue planet may look visibly altered.

“There will be a noticeable difference in the color of 50 percent of the ocean by the end of the 21st century,” Dutkiewicz says.

“It could be potentially quite serious. Different types of phytoplankton absorb light differently, and if climate change shifts one community of phytoplankton to another, that will also change the types of food webs they can support.“

Links :

- BBC : Climate change: Blue planet will get even bluer as Earth warms

- The Guardian : Rising temperatures to make oceans bluer and greener

- National Geographic : Climate change will shift the oceans' colors

- GeoGarage blog : Computing the ocean's true colors

No comments:

Post a Comment