From Caledonian Mercury

Alexander Dalrymple was an extraordinary fellow, even for a son of the Scottish Enlightenment.

He was a secretary, navigator, hydrographer, trade economist, political pamphleteer, author and collector of songs and poetry.

He drew hundreds of charts for the East India Company and the Royal Navy.

He helped establish the Beaufort scale to measure wind speed.

And he was the first westerner to predict the existence of a great southern continent.

The painting is dated to about 1765 and is the only known

likeness of Dalrymple in the UK.

He was one of those restless Scots who helped build the British Empire in the 18th century.

And he is remembered to this day as the founder, in 1795, of the UK Hydrographic Office, which produces the famous Admiralty Charts – the 3,300 maps which cover the world’s oceans, shipping lanes, ports and harbours.

The latest Alexander Dalrymple Award was presented last year to Dr Hideo Nishida of the Japanese coastguard for his work on tsunamis and his agency’s response to the major tsunami which struck north-eastern Japan in March 2011.

It must be said that Dalrymple was not an easy man to work with.

He was argumentative, independent-minded, head-strong, arrogant, often insulting.

His later portraits make him look like an angry bull.

He was sacked three times by various employers and his doctor declared that he “died of vexation.” But he made the world’s seas a safer place and he opened new trade routes which brought riches – if not to himself – then to his country and the global economy.

His oldest brother was Lord Hailes (right), the judge and historian, who was a leading light of the Scottish Enlightenment.

The family could not afford to send Alexander to Eton like his older brother and he even had to leave the local school in Haddington when his father died.

His brother tried to educate him at home but already there were signs of rebellion.

He was sent to a secretarial school in London but again things did not go particularly well.

Eventually his uncle, General St Clair, managed to get him a job with the East India Company and at the age of 15 he found himself posted to Madras.

Arrowsmith map - dedication to Alexander Dalrymple

He began as an under-storekeeper, but the Governor, Lord Pigot, saw the boy’s potential and moved him into the secretarial office, even giving him lessons in writing and arranging for him to learn accounting.

But the quiet life of a company clerk was not enough for Alexander.

He thought the company was not taking full advantage of the trading possibilities in south-east Asia.

He resigned his post and managed to wangle his way onto a ship to China and Borneo where he negotiated his own trade agreement with the Sultan of Sulu.

But when his vessel arrived to begin trading and take on its cargo, he found that small-pox had killed off many of the merchants involved and the Sultan’s politics had suddenly changed.

by Alexander Dalrymple, [London : printed for the Author, 1770]

He had learnt a lot about the geography of the Far East.

He wrote a book entitled “An Account of the Discoveries Made in the South Pacific Ocean” which included many of his own charts, an account of a new passage south of New Guinea by the Spanish explorer Luis Vaez de Torres, and a theory that there must exist a vast southern continent “to maintain a conformity in the two hemispheres.”

It might, argued Dalrymple, contain a population as big as China or India and be a goldmine for trade.

The recent discovery of this sheet, however, pushes back the beginning of Admiralty chart publishing to at least November of the preceding year.

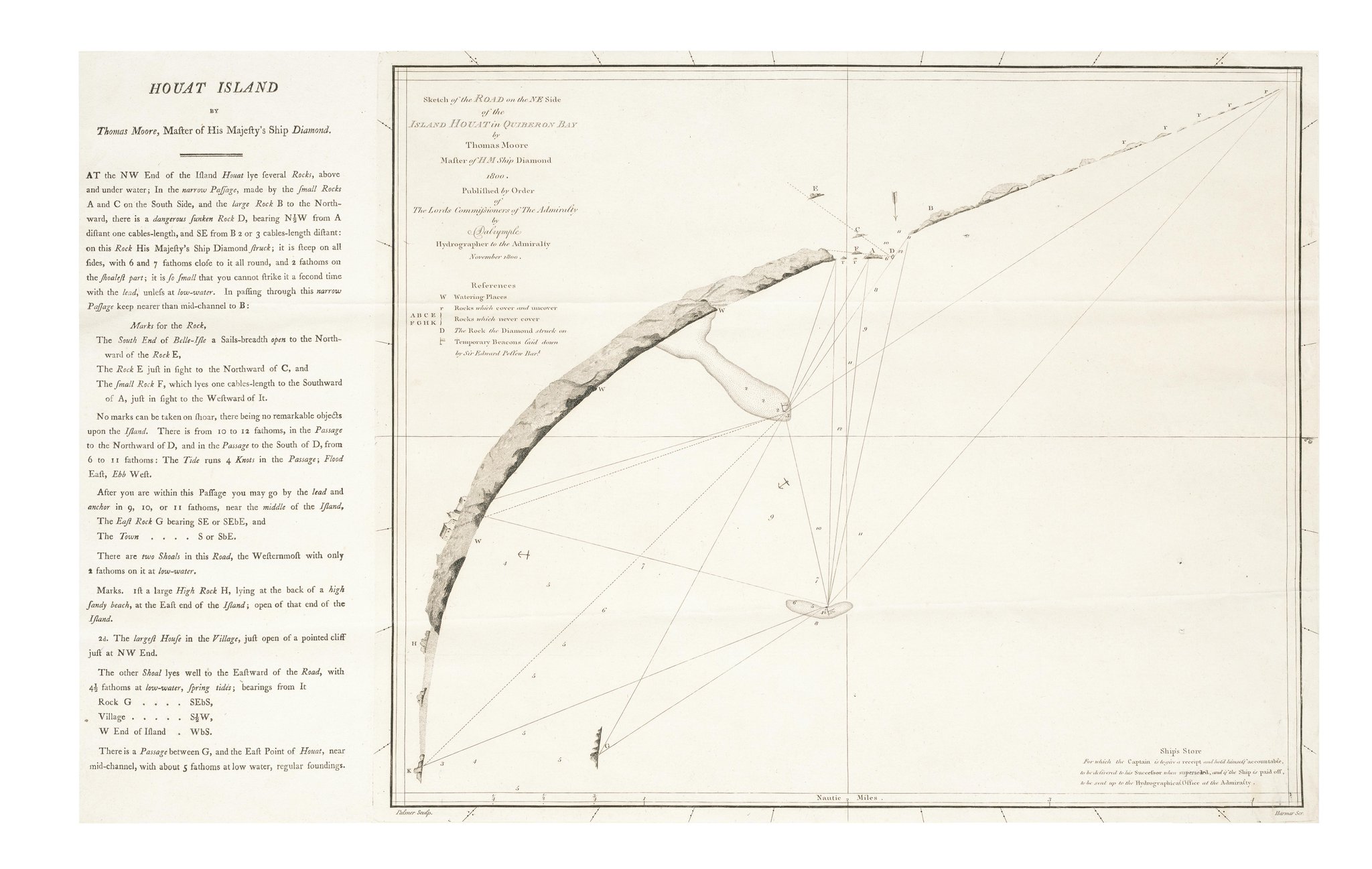

Admiralty charts issued up to the end of Alexander Dalrymple's tenure as Hydrographer to the Admiralty in 1808 look very much like the charts which Dalrymple published at the same time in his capacity as Hydrographer to the East India Company, and the two can easily be confused.

This chart depicts Houat Island in Quiberon Bay, off the south coast of Brittany

(By courtesy of Lieutenant Commander Andrew David RN).

While in London he also wrote a book, Practical Navigation, in which he argued the case for a standard measurement for wind speed to help navigators compare conditions at sea.

It was an idea first proposed by the civil engineer John Smeaton, who was working at the time on windmills.

But it was Dalrymple who brought it to the attention of Francis Beaufort who went on to develop the famous Beaufort Scale.

The young Dalrymple – he was only 30 years old – so impressed the scientific community in London that he was elected to be a fellow of the Royal Society, with famous names like Benjamin Franklin on his nomination papers.

He was even considered for the Society’s expedition to Tahiti to observe the transit of Venus in 1769.

But because he insisted on commanding the expedition himself , he was passed over in favour of Captain James Cook and the scientist Joseph Banks.

Cook and Banks however drew heavily on Dalrymple’s book and when they opened their secret orders in Tahiti, they went on to “discover” the great southern continent he had predicted.

They sailed right round New Zealand and then landed in Australia in April 1770, claiming it for the British Crown.

We now know of course that some 50 western ships had visited Australia before Cook – the earliest, a Dutch expedition in 1606 – and no one knew just how big the island was or that it already contained 250 aboriginal tribes.

Back in London, Dalrymple continued to insist that a large continent remained undiscovered – the famed Terra Australis Incognita.

He poured scorn on Cook, saying : “ I would not have come back in ignorance.”

Somewhat in a huff, he went off again to the Far East and found that his mentor Lord Pigot was prepared to have him back in the East India Company as its official hydrographer.

He produced hundreds of detailed charts of the seas and ports – arguing with anyone and everyone over the names of obscure islands and again proposing new trade links with various kings and potentates.

He was passed over for promotion, sacked and taken back on again, in a turbulent career with the company.

He wrote intemperate articles about missed opportunities for trade. In one, he opposed the establishment of a penal colony at Botany Bay, calling it a “mad scheme” which would undercut the East India Company’s business in South-East Asia.

He thought prisoners should be sent to Tristan da Cunha instead.

Ironically, his great rival, Captain Cook, meanwhile set out on a second expedition, in 1772, to find the Terra Australis Incognita. But he turned back at 70 degrees south, just as he was about to run into Antarctica, the real southern continent.

That remained undiscovered for another 45 years.

from 1770 Voyages of The South Pacific - Alexander Dalrymple

(eBay sales 17,700US$)

Alexander Dalrymple was not around to see it, of course.

But he spent the last few years of his life in his most important job, the first official hydrographer for the Royal Navy.

From 1795 until his death 13 years later, in 1808, he worked on producing a comprehensive set of charts for the Admiralty of the world’s most important ports and seas.

But he also found time to produce a stream of articles on current affairs – the American war, the currency, the state of shipping, the North American fur trade, the wickedness of the Spanish colonists and, of course, various commentaries on the state of the East India Company.

He wrote a critique of Tom Paine’s “Rights of Man” which he entitled “The Poor Man’s Friend.”

He also wrote a history of the industries of the Far East.

And he put together a collection of English poetry and songs and included “an appendix of original pieces.”

By the end of May 1808, the Admiralty was trying to persuade an ever more cantankerous Dalrymple to retire.

He refused to do so and was promptly sacked.

He died less than a month later.

I like the title of his last published work: “Thoughts of an old man of independent mind, though dependent fortune.”

Links :

- National Library of Australia : Dalrymple collection

No comments:

Post a Comment