From History Defined by Carl Seaver Sealand is a tiny country located in the North Sea, about 12 miles off the coast of England.

It is considered the smallest country in the world, which once had a population of 50 people.

Sealand was created in 1967 by Paddy Roy Bates, who declared it an independent nation after he and his family occupied a disused Navy fort near the HM Fort Roughs.

The story of Sealand is fascinating, and it has been home to some exciting events over the years.Sealand

What is it, And Where is it Located?

Sealand is a strange place.

It’s the smallest country in the world and on a platform in the North Sea that was once used as a military fort.

In 1967, Paddy Roy Bates, a retired British army major, declared himself ruler of the country, and his family has been running it ever since

Sealand has had its share of controversy over the years, and it remains an oddity to this day.

It started as an idea that became a gift to his wife Joan for her birthday.

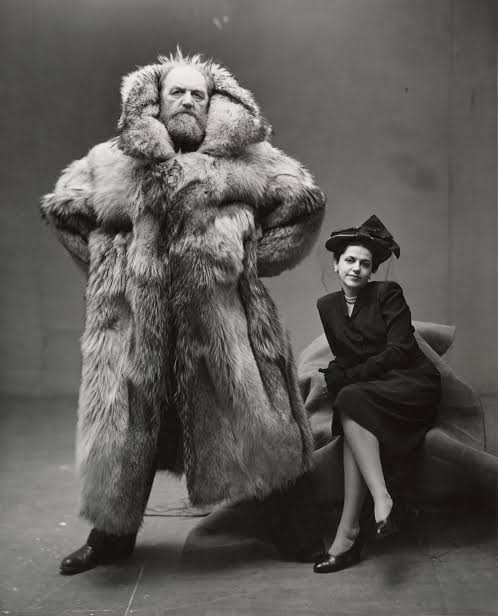

Roy and Joan Bates.

Credit: Martyn Goddard/Alamy

On Christmas Eve in 1966, Bates took a boat and drove it to the platform.

Then, using a grappling hook, rope, and his wit, he climbed to the top of the platforms and claimed them, conquering them for his wife as a gift.

The gift itself was odd and was nothing fancy to look at; in the past, it had a much different purpose.

In the early 1940s, around WWII, the His Majesty’s Ford (HMF) Roughs Tower was an outpost and one of five to defend the Thames.

It was about the size of two tennis courts set on top of two hollow concrete towers approximately 60 feet above the ocean.

In its heyday, the platform was manned was over a hundred British military men armed to the teeth with anti-aircraft guns.

These guns stood between the Nazi bombers and London during the Blitz.

The fort was abandoned in the late 1950s, well after the German’s defeat, and by the time Roy came to claim it, the UK had long since forgotten it.

However, that didn’t stop British Authorities from ordering him to abandon it.

Despite their warnings, Roy Bates was a hardened man who had served since he was 15, first in the Spanish Civil War and then in North Africa, the Middle East, and Italy

during WWII.So, Roy Bates wasn’t scared of bureaucrats trying to tell him what to do.

Instead, he ignored their warnings and continued what he was doing, and Sealand’s reputation grew as a result.

The Sovereignty of a Micro-nationThe story starts with Roy Bates establishing a pirate radio station on the platform in 1965.

At the time, it was illegal, but Bates saw an opportunity.

He first started his radio station at an old WWII fort called Knock John, another one of the forts used to repel the German assault, now decommissioned.

In all honesty, Bates started this pirate radio station because, like many others, he did not enjoy the BBC’s monopoly on the airwaves.

At the time, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) was the only legal radio station, and they had complete control of what people could and couldn’t listen to

because of a Royal Charter.

Bates started his pirate radio station because he saw this as an opportunity to give people the music they wanted to hear, not just what the Post Office or the government wanted them to hear.

However, the British authorities made it impossible for Bates and other pirate radio stations to broadcast, so the retired navy officer gave it up.

At the time, leaders may have thought that Bates would give up Fort Roughs, but he doubled down.

It’s said that after a night with friends and comments from his wife, Bates named the fort the “Principality of Sealand” on September 2, 1967.

It was his wife’s birthday, and not long after, his family moved with him to the smallest country in the world.

The establishment of this unrecognized sovereignty in British waters, just seven miles off the coast of Suffolk, quickly caught the attention of the UK government.

The British authorities were unhappy with this turn of events, describing Sealand as “an illegal occupation of a structure not recognized as an island under international law.”

On the other hand, Bates was adamant that Sealand was its own country and that he was its rightful leader.

Authorities saw this as a version of Cuba and were determined to stop it.

So in 1968, the military sent helicopters to destroy the remaining outposts to keep any more principalities from popping up.

Again, Roy and his family saw a potential threat to their livelihood.

Sealand

Then, when UK officials were working on a buoy near the principality, Michael, Roy’s son, fired a .22 pistol at them.

In response, the British government brought charges against Michael for discharging and illegal possession, but the court didn’t rule as expected.

Since the actions happened outside British jurisdiction, they were unpunishable by the law.

Sealand believed this to be recognition of their country, so they declared independence.

German UsurpersIn 1978, a West German businessman named Alexander Gottfried Achenbach declared himself the “Prime Minister” of Sealand and staged a coup.

Bates had left Sealand to deal with a family emergency, and during his absence, Achenbach and some German and Dutch mercenaries took over the platform.

They held Prince Michael hostage and locked him away for four days.

Bates quickly assembled a team to retake the platform without incident.

Many of Achenbach’s group fled during the operation, but Bates decided to hold Achenbach hostage.

When a UK ambassador negotiated with Bates, he finally released Achenbach.

UK Expanse

In the 1980s, the British government expanded its territorial waters to remove any legitimacy to Sealand’s claims.

Nevertheless, Bates continued to assert that Sealand was an independent country.

His response was to issue Sealand’s currency, passports, and stamps.

The country even had a flag and a motto E Mare, Libertas, which means “From the sea, freedom.”

Despite Some Issues, Sealand is Still Out There Today

Unfortunately, in the 1990s, Sealand had to rescind its passports after people used some for criminal activity.

In 2006 a destructive fire broke out on the platform and destroyed the main power generator, prompting a brief sale period of the platform in 2007.

However, the citizens devised a solution and fixed the issues.

Sealand is still out there today, and Michael Bates and his family remain involved in Sealand’s well-being and operate it as an independent country.

They’ve even established full-time security on the platform.

The principality even has its website and sells souvenirs, like coins, patches, and T-shirts, to help with costs.

Incredibly, such a small structure in the middle of the sea has maintained its sovereignty for over 50 years.

Sealand has had a mercenary invasion and constant threats from the UK government, but they stood firm.

Though any other country does not officially recognize it, Sealand is the smallest country in the world and has an exciting history.

What started as a World War II fort became a family project and an independent nation.

Despite its rocky past, Sealand continues and is recognized, even if it’s unofficially, as the smallest country worldwide.

Links :

with new world map (4000) including new ice extent

with new world map (4000) including new ice extent

Sealand

Sealand