Yemeni fishermen moor their boat in Aden after fishing off the coast of Yemen's southern port city (AFP)

Hundreds of fishermen have been killed or injured at sea since the war began.

Those left are forced to sail further - and risk even more

Catching fish for a living in

Yemen isn’t only about jumping in a boat and throwing a net into the sea. You need to also say goodbye to your family and prepare them for the fact that they might never see you again.

Because what was once a fairly routine occupation has, since war started in 2014, often become a matter of life and death.

This has little to do with storms or treacherous currents at sea, but rather the fact that after the

Saudi-led coalition declared most of Yemen's territorial waters a conflict zone, fishermen have frequently been fired upon and killed when attempting to work there.

As of August 2019, at least 334 fishermen had been reported killed or injured since 2015,

according to statistics from Yemen's fisheries authority.

Others had been arrested and had their boats seized, while some were now detained in Saudi-run prisons in Yemen.

'When we try to fish in deeper areas, where there are a lot of fish, Apache helicopters chase us and the fighters shoot at us'

- Ahmed Futaih, fisherman in Aden

“We are allowed to fish in specific areas near to the beach," Ahmed Futaih, a fisherman in his 40s from Aden city, told Middle East Eye.

"But when we try to fish in deeper areas, where there are a lot of fish, Apache helicopters chase us and the fighters shoot at us or their military boats arrest us and seize our boats.

"One of my colleagues was arrested by the Saudi-led coalition and they seized his boat. They only released him after he signed papers saying that he would not fish in the banned areas again.”

Local reports

estimate that of Yemen's approximate 100,000 fishermen, since 2015 over a third (37,000) have quit and thus lost their income.

This in one of the world's poorest countries, where the war has resulted in tens of thousands of people living in famine-like conditions and which has been declared by the United Nations as the

world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

Driven further out to sea

Desperate to continue earning a living and feeding their family, some fishermen, such as Futaih, have been forced to go out far beyond Yemen's territorial waters and head for Somalia, where there are plentiful fish stocks.

There they are safe from the coalition's bullets and punishment, but not from other hazards.

“Many fishermen decided not to continue in this dangerous job and they went to look for an alternative," Futaih told MEE.

"But I don’t have any other profession to help me to provide for my 11 family members.

“Now, I fish in the allowed Yemeni waters and sometimes I go to Somali waters. When Somali coastguards arrest us, they seize all our fish and take our boats and sometimes they shoot at us when we try to flee.”

Yemeni fishermen sell their catch at a market amid spiralling prices, in the southern port city of Aden on 28 September 2021 (AFP)

Yemeni fishermen sell their catch at a market amid spiralling prices, in the southern port city of Aden on 28 September 2021 (AFP)

Futaih said that the Yemeni fishermen had built a relationship with their Somali counterparts and that they sometimes worked together, dividing the catch between them.

The Somali fishermen often had sympathy for their Yemeni colleagues, he added.

“They can be helpful towards Yemeni fishermen and allow us to fish in Somalia's waters, but we need to pay fees,” Futaih said.

“But some of us can’t afford the fees, so we have to fish illegally”.

Futaih said that it costs them more time and fuel to sail to Somalia (whose nearest coastline is 200kms from Aden), but that apart from the costs, the main danger was being spotted by the Somali coastguard.

“When we try to flee from the Somali coastguards, they shoot at us but usually we manage to escape," Futaih told MEE.

"But if they do manage to arrest us, that usually means going to prison.”

In March 2021, a

Somali court fined 3o Yemeni fishermen $700 each and seized their boats for illegally fishing in the East African country's territorial waters.

At the same time, the court released eight Yemeni children who had also been arrested on the seized boats.

'Otherwise I will starve to death'

Malik, a fisherman who inherited this job from his father, told MEE that while Yemen's waters may not be safe to fish in for Yemenis in small boats using traditional methods, large commercial fishing vessels from the Gulf states were trawling for fish every day.

“It isn’t safe for us who fish in the traditional way to fish in Yemen, but the Emirati and Saudi fishing vessels are allowed to dredge our fish from anywhere they want,” Malik said.

Malik was arrested by the Somali coastguard and released last year after they had seized his boat and he'd paid a fine to Somali authorities.

'Every day I go to sea, I tell my family that I might not return as the threats in the sea are great, either in Yemen or Djibouti or Somalia'

“I was fishing with other fishermen in the same boat and the Somali coastguard chased us and shot at us. We didn’t manage to flee so we surrendered to them,” Malik said.

Malik was sent to a Somali prison for a month and only released when he'd paid a fine.

“I don’t have a boat now, but I hire one and sail to fish in Yemeni waters or near Somalia's waters," Malik told MEE.

"That’s my only choice, otherwise I will starve to death together with my wife and three children."

The Djibouti coastguard has also arrested Yemeni fishermen.

The last time was in November 2021, when the six fishermen from Aden were detained.

Desperate situation

Yasmin Mohammed, from Aden, told MEE that she used to cook fish every day in the family home.

It was such a staple in the family's diet that her children would sometimes ask her for a break from it.

“Fish used to be very cheap and most families in Aden could easily afford it. But since 2015 prices have been increasing and it is now unaffordable,” she said.

“Fish that used to cost 1,000 ($4) Yemeni riyal now costs YR10,000 ($40).”

Yasmin, a widow providing for four children, said that she hardly buys fish anymore as only rich families can afford it.

The port city of Aden lies in the Gulf of Aden and many of its residents work as fishermen.

The fish they caught fed people far beyond Aden.

Saeed, a fisherman from Aden's waterfront Sira district, said that fish prices had risen dramatically because of the increasing dangers and challenges that Yemini fishermen now face.

“Fishermen have specific areas to fish in Yemeni waters where there are not enough fish and the fish aren’t the best kinds," he told MEE.

"When they sail to Somalia or Djibouti or buy from African fishermen, that costs a lot, so fish in Aden isn’t as cheap as before.”

Saeed said that many fishermen had drowned as they headed directly into rough seas to avoid being chased by coastguards, either in Somalia or Yemen.

It is a desperate situation, which can only get worse as the war in Yemen enters its eighth year, with no sign that a resolution is near.

Meanwhile, Yemen's fishermen find themselves in an impossible situation.

“In Yemen, the coalition shoots at us and in Somalia, it is the coastguard," Malik told MEE.

"So we only have two choices, and they are both difficult.”

Links :

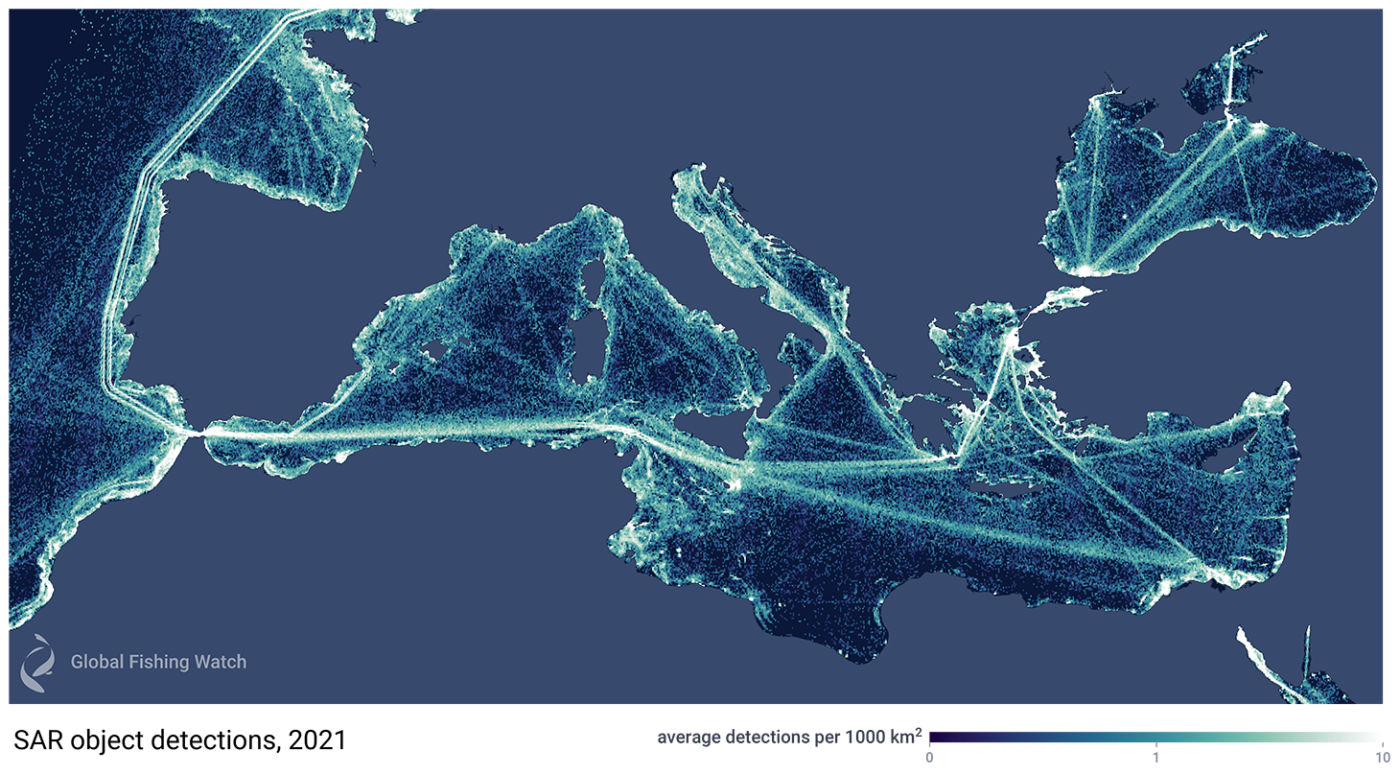

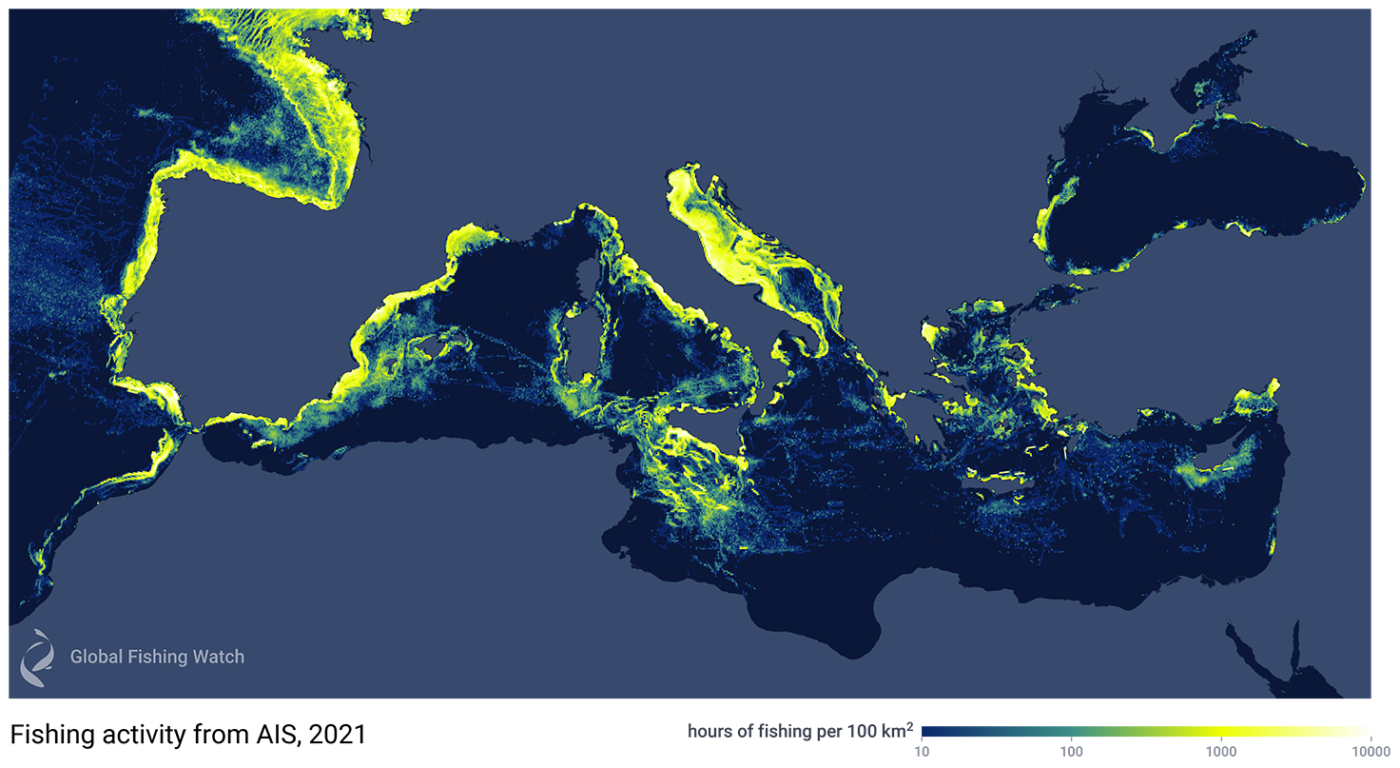

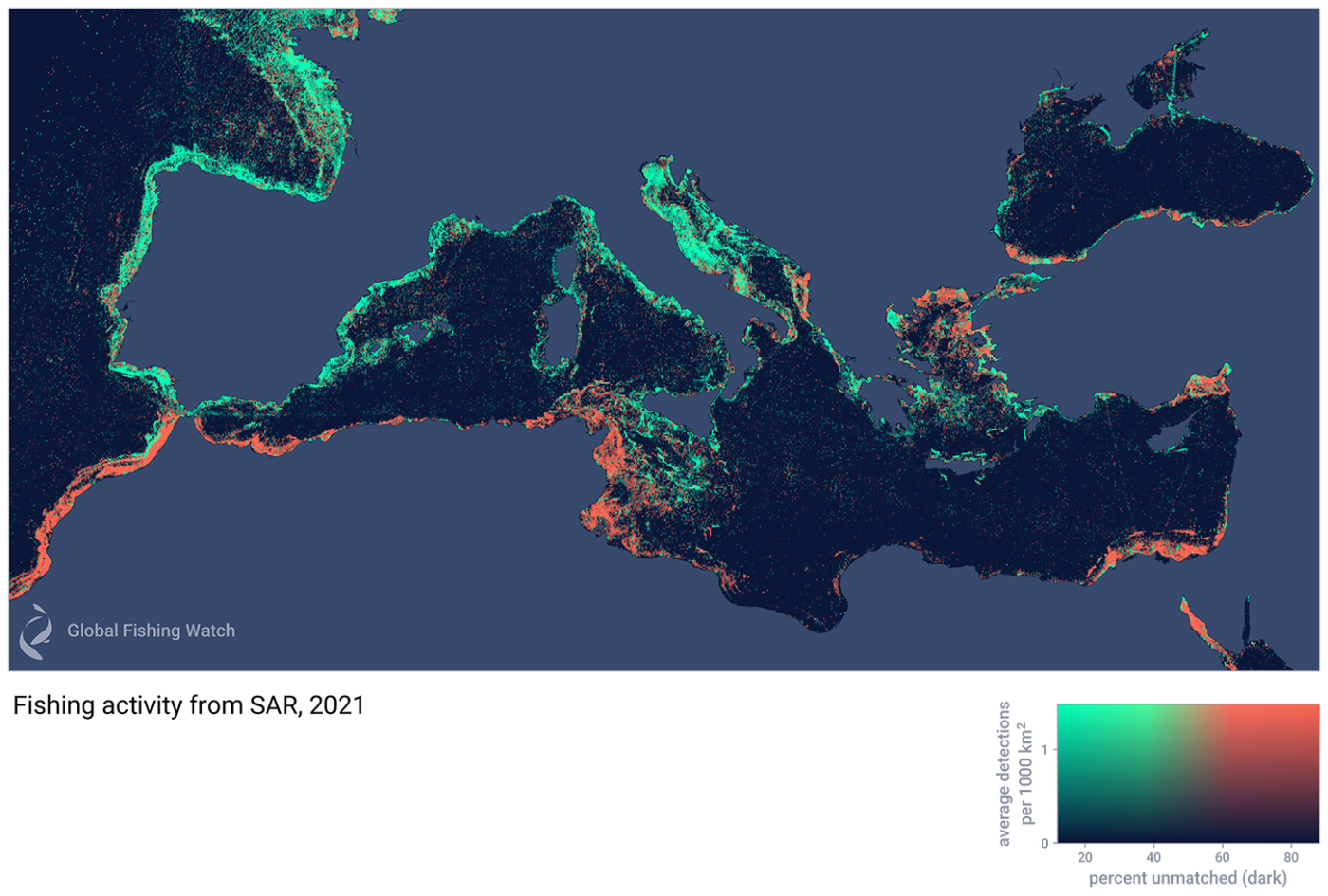

Satellite radar imagery reveals the true scale of vessel activity in the Mediterranean Sea.

Satellite radar imagery reveals the true scale of vessel activity in the Mediterranean Sea. Fishing activity in the Mediterranean Sea and surrounding waters in 2021, when detected using AIS data alone, shows AIS-broadcasting vessels (yellow areas), but fails to show many non-broadcasting “dark vessels”— for example, very little is shown along North Africa.

Fishing activity in the Mediterranean Sea and surrounding waters in 2021, when detected using AIS data alone, shows AIS-broadcasting vessels (yellow areas), but fails to show many non-broadcasting “dark vessels”— for example, very little is shown along North Africa.  Fishing activity in the Mediterranean Sea and surrounding waters in 2021 is detected with Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR).

Fishing activity in the Mediterranean Sea and surrounding waters in 2021 is detected with Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR).

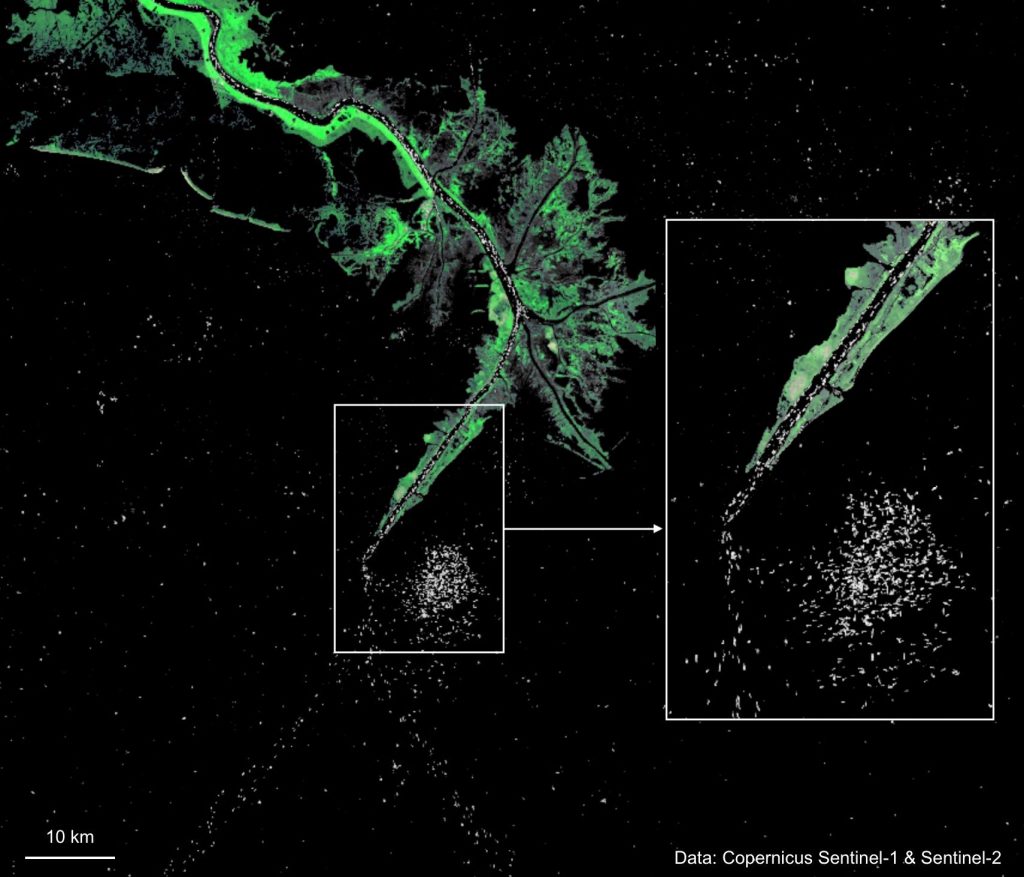

Mississippi River delta and the Gulf of Mexico. Land surface from Sentinel-2 false color composite B4/B8/B2 on 2019-04-03.

Mississippi River delta and the Gulf of Mexico. Land surface from Sentinel-2 false color composite B4/B8/B2 on 2019-04-03. Yemeni fishermen sell their catch at a market amid spiralling prices, in the southern port city of Aden on 28 September 2021 (AFP)

Yemeni fishermen sell their catch at a market amid spiralling prices, in the southern port city of Aden on 28 September 2021 (AFP)