Saturday, January 16, 2021

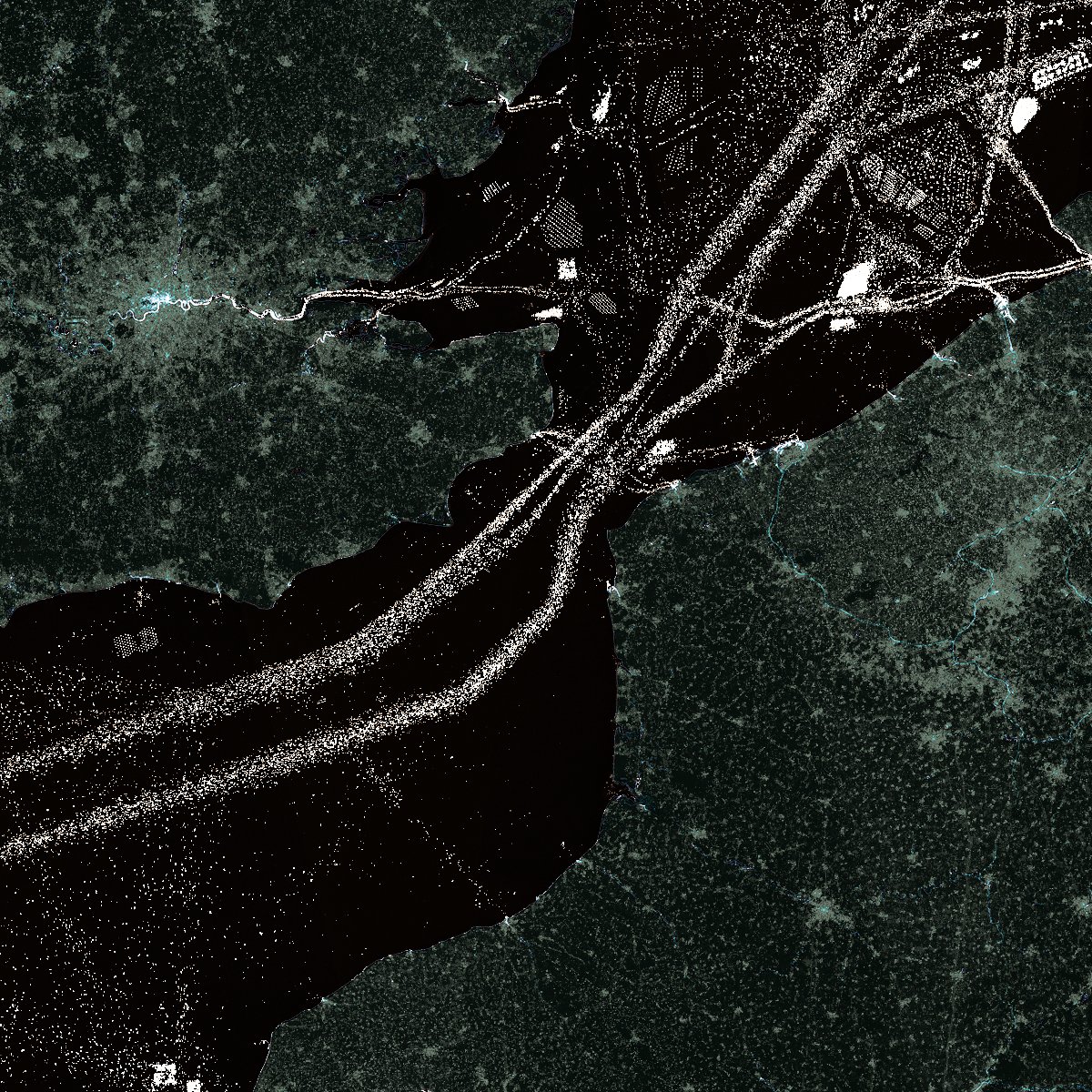

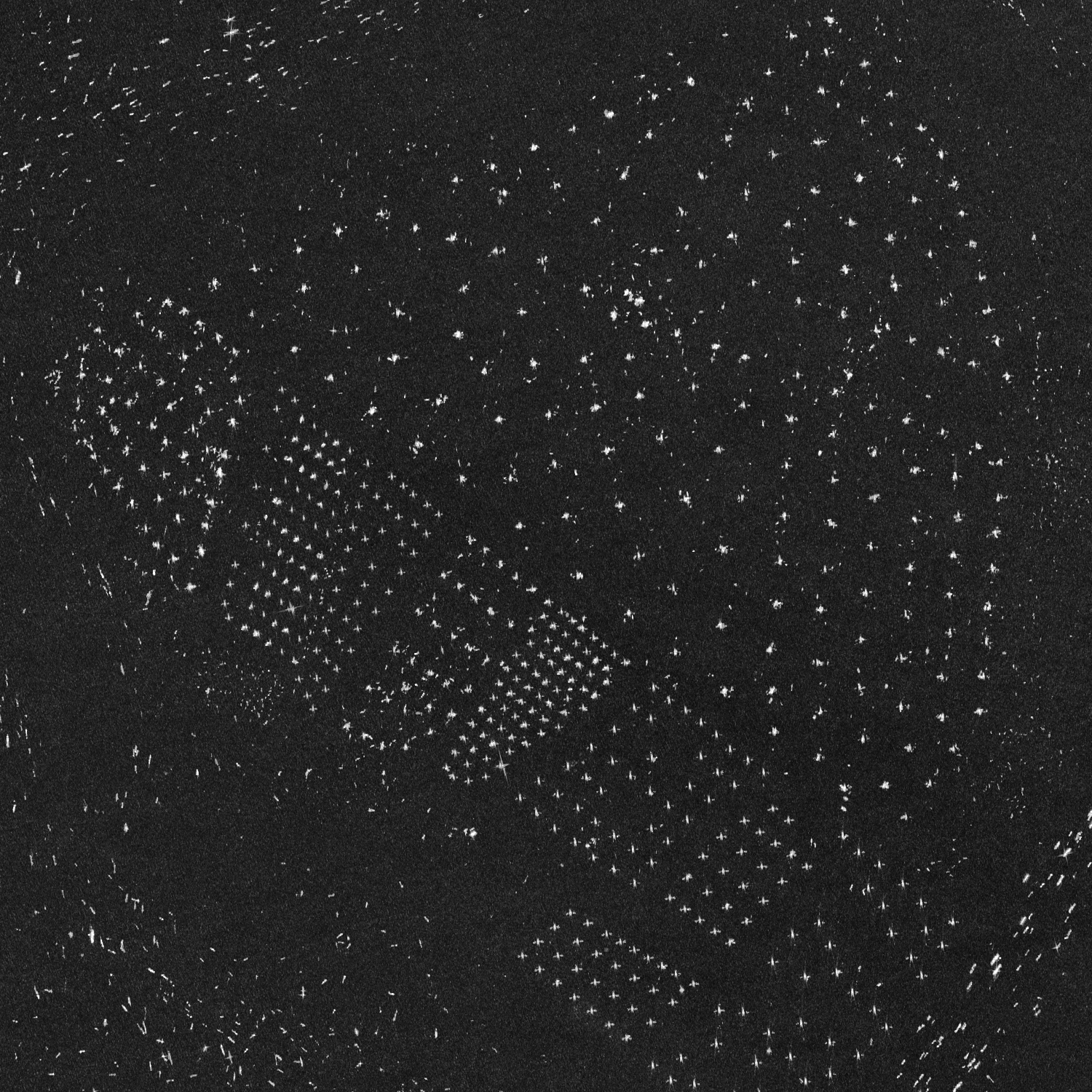

Image of the week : In a year's worth of photos, the Sentinel-1 satellites materialise the Channel maritime motorway

From Ciel&espace

The Channel maritime motorway has two lanes to avoid collisions between the many ships using it.

The Channel maritime motorway has two lanes to avoid collisions between the many ships using it.

The North Sea is studded with pre-polar installations and wind farms. Credit: ESA.

Already in 2019, the European Space Agency had published a similar image that accumulated photos taken over three years, between 2016 and 2018.

The English Channel in 2020, as seen by @CopernicusEU's Sentinel-1 imaging radar. This maximum reflectivity composite shows the year in shipping lanes, offshore wind farms, &c. pic.twitter.com/9WjxEkDcB1

— Tim Wallace (@wallacetim) December 31, 2020

In the 2020 image, which was broadcast on 31 December on Twitter by journalist Tim Wallace of the New York Times, in addition to the cargo ships transiting the English Channel, the ferries sailing between Calais and Dover were also shown, as well as the wind farms installed at sea, which drew geometric patterns.

Friday, January 15, 2021

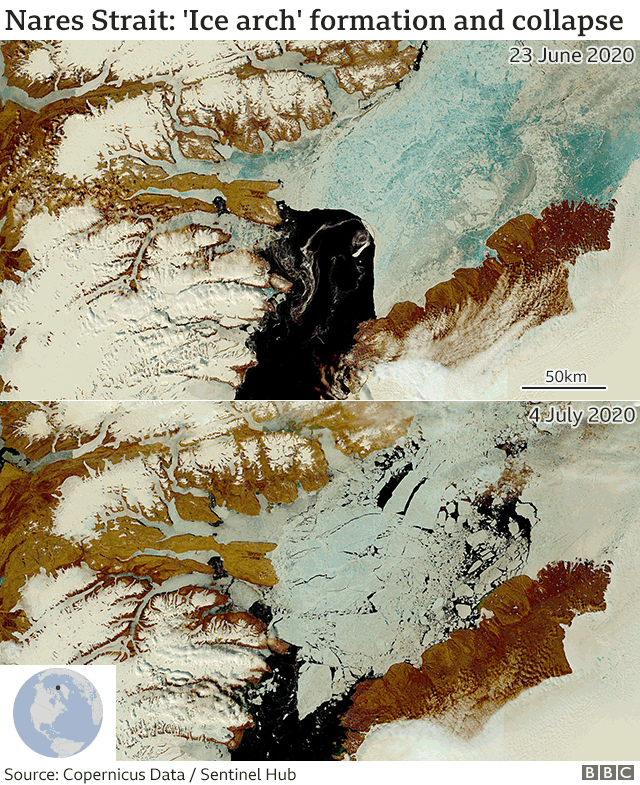

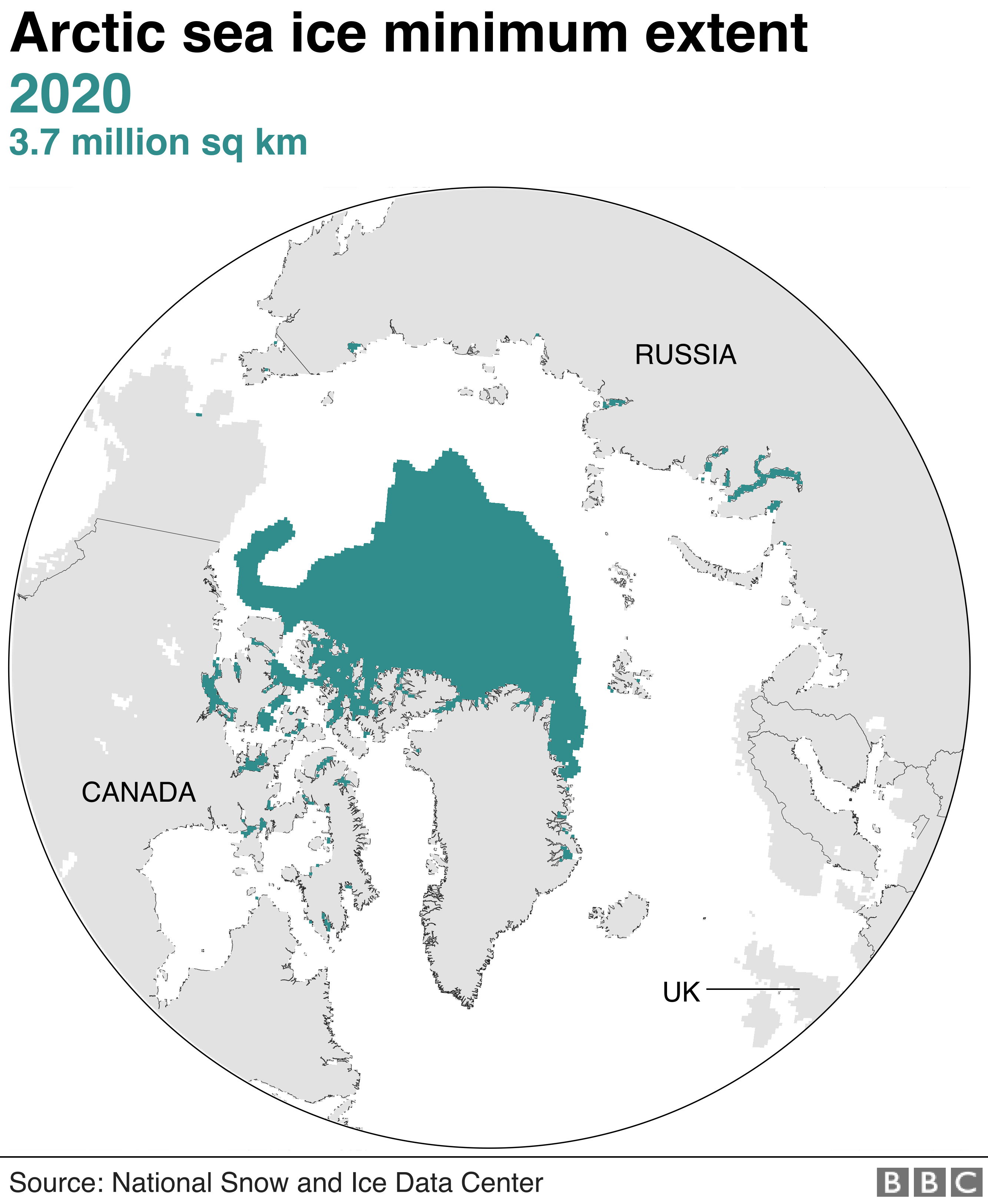

Climate change: Weakened 'ice arches' speed loss of Arctic floes

From BBC by Jonathan Amos

Look down on the Arctic from space and you can see some beautiful arch-like structures sculpted out of sea-ice.

They form in a narrow channel called Nares Strait, which divides the Canadian archipelago from Greenland.

"They look just like the arches in a gothic cathedral," observes Kent Moore from the University of Toronto.

"And it's the same physics, even though it's ice.

The stress is being distributed all along the arch and that's what makes it very stable," he told BBC News.

But the UoT Mississauga professor is concerned that these "incredible" ice forms are actually being weakened in the warming Arctic climate.

They're thinning and losing their strength, and this bodes ill, he believes, for the long-term retention of all sea-ice in the region.

Directly to the north of Nares Strait is the Lincoln Sea.

It's where you'll find some of the oldest, thickest floes in the Arctic Ocean.

It's this ice that will be the "last to go" when, as the computer models predict, the Arctic becomes ice-free during summer months sometime this century.

There are essentially two ways this old ice can be lost.

It can be melted in place in the rising temperatures or it can be exported.

And it's this second mode that's in play in Nares Strait.

The 40km-wide channel's arches act as a kind of valve on the amount of sea-ice that can be pushed out of the Arctic by currents and winds.

When stuck solidly in place, typically from January onwards - the arches shut off all transport (sea-ice can still be exported from the Arctic via the Fram Strait, which is the passage between eastern Greenland and Svalbard).

But what Prof Moore's and colleagues' satellite research has shown is that these structures are becoming less reliable barriers.

They are forming for shorter periods of time, and the amount of frozen material allowed to pass through the strait is therefore increasing as a consequence.

"We have about 20 years of data, and over that time the duration of these arches is definitely getting shorter," Prof Moore explained.

"We show that the average duration of these arches is decreasing by about a week every year.

They used to last for 250-200 days and now they last for 150-100 days.

And then as far as the transport goes - in the late 1990s to early 2000s, we were losing about 42,000 sq km of ice every year through Nares Strait; and now it's doubled: we're losing 86,000 sq km."

Prof Moore says we need to hang on to the oldest ice in the Arctic for as long as possible.

If the world manages to implement the ambition of the Paris climate accord and global warming can be curtailed and reversed, then it's the thickest ice retained along the top of Canada and Greenland that will "seed" the rebound in the frozen floes.

The area of oldest, thickest ice, he adds, is also going to be an important refuge for those species that depend on the floating floes for their way of life - the polar bears, walruses and seals.

"My concern is that this last ice area may not last for as long as we think it will.

This is ice that is five, six, even 10 years old; so if we lose it, it will take a long time to replenish even if we do eventually manage to cool the planet."

Prof Moore and colleagues have published their latest research in the journal Nature Communications.

- BBC : Satellites capture Arctic ice shelf split / 'The sea-ice is dying': Historic Arctic trip ends / Arctic sea-ice shrinks to near record low extent

- Phys : Ice arches holding Arctic's 'last ice area' in place are at risk, researcher says

- Science Alert : The Arctic's 'Last Ice Area' Is Showing Worrying Signs of Fragility

Thursday, January 14, 2021

Saildrone launches 72-foot Surveyor, revolutionizing ocean seabed mapping

The new Saildrone Surveyor is the world’s most advanced uncrewed surface vehicle, equipped with an array of acoustic instruments for high-resolution shallow and deep-water mapping.

Less than 20% of Earth’s oceans have been mapped using modern, high-resolution technology—we know more about the topography of the Moon and Mars than we do about our own planet.

And yet, knowing the shape of the seabed is critical to understanding ocean circulation patterns, which affect climate and weather prediction, tides, wave action and tsunami wave propagation, sediment transport, underwater geo-hazards, and resource exploration.

Saildrone is excited to announce it has launched the Saildrone Surveyor, a new 72-foot uncrewed surface vehicle (USV) equipped for high-resolution mapping of the ocean seafloor.

The Surveyor carries a sophisticated array of acoustic instruments for both shallow and deep-water ocean mapping; the Kongsberg EM 304 multibeam echo sounder is capable of mapping the seafloor down to 7,000 meters below the surface.

The Surveyor also carries two state-of-the-art Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers (ADCPs), the Teledyne Pinnacle 45 kHz ADCP and the Simrad EC150-3C ADCP, to measure ocean currents and understand what is in the water column.

The Surveyor is also equipped with the Simrad EK80 echo sounder for fish stock assessments.

The Surveyor is equipped with a sophisticated array of acoustic instruments including the Kongsberg EM304 multibeam sonar, Simrad EK80 echo sounder, Teledyne Pinnacle ADCP, and Simrad EC150 ADCP.

The launch of the Saildrone Surveyor coincides with the start of the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development and presents a paradigm shift in enhanced seabed mapping.

Ocean mapping is currently done with very large and expensive crewed ships.

The Saildrone Surveyor is a scaled-up version of the Saildrone Explorer, the 23-foot wind and solar-powered saildrone, which has been proven in numerous operational missions for science, ocean mapping, and maritime security, covering more than 500,000 nautical miles from the Arctic to the Antarctic.

Like the Explorer, the Saildrone Surveyor is uncrewed and uses renewable solar energy to power its robust sensor suite; the Surveyor delivers an equivalent survey capability, but at a fraction of the cost and carbon footprint of a traditional survey ship and without putting human health and safety at risk.

“The launch of the Surveyor is a huge step up, not just for Saildrone’s data services but for the capabilities of uncrewed systems in our oceans,” said Richard Jenkins, founder & CEO of Saildrone.

“For the first time, a scalable solution now exists to map our planet within our lifetime, at an affordable cost.”

Enhanced seabed mapping is vital for the security, safety, and economic health of every country bordering the ocean and critical to the growth of the “Blue Economy,” which, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), is valued at $1.5 trillion a year and creates the equivalent of 31 million full-time jobs.

With the Surveyor, Saildrone aims to accelerate many of the global mapping initiatives that seek to provide better insights into Earth’s processes: Seabed 2030 is a UN-backed joint initiative between GEBCO and the Nippon Foundation to produce a definitive map of the world ocean by 2030, and the 2019 White House Memorandum on Ocean Mapping calls for a national strategy for mapping, exploring, and characterizing the US exclusive economic zone.

“We are excited to see the launch of the Saildrone Surveyor,” said Alan Leonardi, director of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research.

“NOAA is supporting the development and testing of this new uncrewed system because we are confident it will expand the capability of our existing fleet of ships to help us accelerate in a cost-effective way our mission to map, characterize and explore our nation’s deep ocean territory, monitor valuable fisheries and other marine resources, and provide information to unleash the potential of our nation’s Blue Economy.”

The Saildrone Surveyor was developed in part through a public-private partnership with the University of New Hampshire (UNH) and the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) to integrate and test sensors on the Saildrone Surveyor for mapping the seafloor and revealing life in the water column.

While conducting ocean mapping missions, the Surveyor will collect samples of environmental DNA (eDNA) from the water column— DNA originating from the sloughed-off skin, mucus, and excrement of a wide variety of marine animals—which will reveal the genetic composition of organisms inhabiting the water.

This PPP was supported by a three-year grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Office of Ocean Exploration and Research (OER) through the National Oceanographic Partnership Program (NOPP).

Saildrone’s fleet of USVs has logged more than 10,000 days at sea in some of the most extreme weather conditions on the planet.

In 2020, Saildrone completed its first Arctic mapping mission on behalf of NOAA’s National Ocean Service, and in 2019, Saildrone completed the first autonomous circumnavigation of Antarctica, collecting critical carbon data related to climate science.

Media coverage

To download assets of the Saildrone Surveyor and request an interview or high-resolution assets, visit our Media Room.

Links :

Wednesday, January 13, 2021

The polar vortex has just been disrupted. What does this bode?

From Mashable by Mark Kaufman

The stratosphere is a powerful place.

Perhaps the most influential guitar ever devised is even named after this lofty layer in the atmosphere, which exists between some 10 to 30 miles up in the sky.

And during each dark winter, the Arctic's polar vortex — strong winds that circle westward around the pole — comes to life in the stratosphere.

It's a normal, reoccurring winter phenomenon.

"Every year we get this big spin up and then it disappears," marveled Andrea Lang, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Albany who researches changes in seasonal winter weather.

This can have dramatic, extreme weather implications in places like the U.S.

and Europe (like plunging temperatures, or even warmer temperatures in some places!).

Now in early 2021, atmospheric scientists saythe polar vortex has been significantly disrupted.

In 2020, much of the East Coast experienced a relatively wimpy winter, in large part because the polar vortex stayed extremely stable and in place atop the globe.

It didn't weaken and wobble around much.

But with a disrupted polar vortex in 2021, there are now better odds for colder air to spill out of the Arctic.

"There's a greater likelihood for the opposite of last winter," said Simon Lee, a Ph.D. student researching the stratosphere in the Department of Meteorology at the University of Reading.

The spinning polar vortex can be disrupted by weather in the lower atmosphere — where there's streaming flows of air called planetary waves traveling around the globe — impacting the stratosphere.

Like waves crashing on the beach, these planetary waves or other major weather events can knock the vortex off balance.

A good analogy is someone nudging a spinning top so it starts to wobble, explained Amy Butler, a research physicist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Chemical Sciences Laboratory.

Crucially, the disruption weakens the vortex's potent winds, and can even reverse them to easterly winds.

These weakened winds ultimately sink to the lower stratosphere where it impacts our weather.

How so?

When these sinking winds push the jet stream down south, it "opens the Arctic fridge," so to speak, allowing blasts of frigid Arctic air to blow down to southerly places.

That's why there was snow in Rome in 2018!

Sometimes the weakening of the polar vortex can be extreme, leading to an event with a somewhat dramatic name, though the event is normal.

It's called "sudden stratospheric warming." And, yes, a major sudden stratospheric warming event is underway in the stratosphere (the event takes place over a matter of days).

It's triggered by things like planetary waves "breaking" into the stratosphere (described above).

This slows the winds and causes air to sink in the vortex — which warms as it sinks (hence the "warming").

Importantly, this considerably weakened, wobbling, elongating vortex can potentially split into two vortices.

This can really push around the jet stream below, making for weather extremes.

"This is looking a little like a splitting event right now," said the University of Albany's Lang.

The weather events that triggered 2021's polar vortex disruption and potential splitting are not yet clear, but will be investigated in the coming months, said the University of Reading's Lee.

For example, a potent "bomb cyclone" (a very powerful storm) over the North Pacific Ocean around the new year may have given the stratosphere a push, on top of other dynamic weather in December.

These events may have disrupted the polar vortex like "nudging a spinning top."

So what should you ultimately expect? Big sudden stratospheric warming events boost the odds for certain types of weather.

"In particular, they are followed by cold extremes over much of northern Europe and Asia, and the Eastern U.S., and anomalously warmer temperatures over the Canadian Arctic and subtropical Asia," explained NOAA's Butler.

(These temperature contrasts are based on where the jet stream, which separates cold air from warmer air, tends to get nudged by a disturbed polar vortex.)

But in the profoundly chaotic atmosphere, few weather events are guaranteed.

For now, the polar vortex has been thrown out of whack.

This winter, you might soon experience some weather extremes.

- WP : The polar vortex is splitting in two, whih may lead to weeks of wild winter

- CNN : The polar vortex may be on its way

- Sire : How changing temperatures in the north pole are creating polar vortex shifts

- Weather : Weaker Polar Vortex Just One Ingredient to an Interesting Pattern for Winter Storms Into February

Tuesday, January 12, 2021

Rapture of the deep

Carried away by love—for risk and for each other—two of the world's best freedivers went to the limits of their sport.

Only one came back

A man walked down the street in Miami Beach the other day.

He appeared preoccupied, a bit hurried, as you might be too if you were about to take a risk that no man ever had.

He had a bronze shaved head, a set of wide and sloping shoulders and a vault for a chest, but it was his left leg that left a question in his wake.

Emblazoned on his calf was a rainbow-colored tattoo of a topless mermaid inside a hammerhead shark.

There was a story behind it, of course.

It was almost—oh, if only it were—a myth.

It was full of mystery and death, magical twists and turns, but whenever it twisted and turned too much, one had only to remember the simple question that began it: What's the half-naked woman doing inside the hammerhead shark?

We could start with the risk.

With a man slipping into the ocean next month off Miami Beach, about to enter a trap where he can't breathe, speak, see or smell.

A man atop a 56-story building who's heading all the way down to the cellar, then back to the roof, only the building is water, all water, and he has no scuba tank.

And no wife, because she never returned from the trap.

And no sleep, because of his anguish and the media and Internet firestorms over his role in her death, and the resulting lawsuit.

Yes, we could start by asking how it happens that the last thing a man in the midst of such grief should be doing becomes his only way out of it and why—here, today, a few billion years into the evolution of life on earth—we've come to this, the ritualized risking of death: extreme sports.

But I've always felt it's better to start with the half-naked woman.

Fully clothed, at this point, of course.

Twenty-one years old.

Staring in disbelief at a poster at a university in La Paz, Mexico, seven years ago.

Him.

There.

On the poster.

The centerpiece of her marine-biology thesis on how the human body adapts to survive at extreme depths.

The risk taker.

Pi-PEEN, as Spanish speakers pronounced his nickname.

Pipín Ferreras.

Coming to Cabo San Lucas, the poster said, to attempt another world-record dive, just a few hours' drive away.

What coincidence! No.

That couldn't be.

What fate.

She found herself on a bus packed with peasants and dogs and chickens, chugging toward Cabo.

O.K., she wouldn't make a fool of herself.

Wouldn't stay long, wouldn't act on this fantasy flitting through her head: the mermaid and the fish man.

She got off the bus, checked into a cheap hotel and headed toward the wharf.

Amazing.

Pipín was offering to give novices a couple of hours of instruction and then let them observe one of his training dives.

It was like Michael Jordan's saying, "Anyone want to let me teach you to play ball, then stand under the basket and watch me scrimmage?" Audrey watched, close up, as he slid into the water and ventilated to prepare for his dive, his lungs and windpipe producing the sound of a bicycle tire being pumped with air: in with the oxygen he'd need to last for nearly three minutes and the 858 feet of water, round-trip, he hoped to cover.

Out with the carbon dioxide and the thoughts that could kill him.

Because where he was going, panic could burn up those 8.2 liters of air in seconds, emotion could devour them in a minute, and even a stray thought could stir his heartbeat and consume the oxygen he'd need to make those last few feet.

She watched him wrap his knees around the crossbar of an aluminum sled, close his eyes and raise one hand to the metal frame overhead: a religious posture.

She knew by heart the religion's history, how man for centuries had been diving for sponge and fish and pearls until Raimondo Bucher, a Hungarian air force officer naturalized as an Italian citizen, dived 30 meters on a dare in 1949.

With that act, man realized he could dive for something far more important than sponge or fish or pearls—he could dive for ego—and competitive freediving, or submerging without the aid of an air tank, was born.

Pipín took one last gulp of air, then vanished.

But Audrey had absorbed her subject so completely that she could shut her eyes and see it all: The sled gathering speed, gliding down a cable anchored with a 100-pound weight, a contraption Pipín had helped devise so that he—and fewer than a dozen others in the world who dedicated themselves to No Limits, the most extreme of the freediving disciplines—could bore deeper and faster than legs and fins could propel him.

Pipín flying past a few scuba divers stationed at intervals along the cable, safety assistants who could do only so much if trouble occurred, because you can't make an unconscious man breathe.

Pipín letting water flood his nasal passages and ear tubes to stave off the searing pain and equalize the relentlessly increasing pressure that could rupture his eardrums.

Pipín's heart rate slowing to 50...40...30...20 beats a minute, his lungs shriveling to the size of potatoes.

His hand, when he reached the bottom, opening an air-tank valve that inflated a lift bag that would rocket him back up.

He burst through the surface in his neoprene wet suit, a missile from the abyss.

He barely seemed to notice her.

Maybe she could go just a little deeper.

Ask him a question or two, make her thesis shine.

She watched from across the table as he sat beside his girlfriend, the blonde knockout, the jazz singer.

What good fortune that Pepe Fernandez, the chief of Pipín's safety divers, had gotten an eyeful of Audrey in her bathing suit and invited her to tag along with the crew for dinner and drinks.

No.

What fate.

The jazz singer rose to sing with her band.

Audrey took a deep breath.

She'd grown up just outside Paris, the only child of scuba-diving parents and the granddaughter of a champion spearfisherman, crazy for dancing and for water and for her dream of becoming an Olympic synchronized swimmer.

But she'd contracted typhoid fever at 14 after her family moved to Mexico City, just as she entered her growth spurt, and it had left her with scoliosis and a spine that swerved like an S.

For four years she was trapped, pinched inside a hard plastic corset.

Her right eyelid drooped and her vision went double as her bewildered body produced antibodies that could locate no infection and settled in her eye.

She couldn't bear it, finally—all the wrecking of her body and her dream.

She was found in the school bathroom, blood puddling from her slit wrists.

There was, she came to realize, one place where she could escape the trap.

For hours each day in the summers she spent on the Mediterranean coast with her grandfather, she flung off the corset, strapped on the scuba tank and slipped into the sea, and everything again seemed possible.

She swam through the fire of shame and came out the other side, a sweet and shy 18-year-old.

In the pictures she sketched, she was a mermaid.

She stared at the empty seat beside the fish man as the jazz singer started to wail.

Trembling, she began to ask him questions.

Pipín purred.

Who was this young beauty who seemed to know so much about him?

He spoke of the sea as she had experienced it, a magical realm where a human might spring free from the prison of self.

Somehow France came up, and he launched into a tirade about the arrogance of the French, then paused and asked Audrey what part of Mexico she was from.

"France," she said, smiling.

Suddenly, the undertow had her.

That's what Pipín did: He grabbed time and love and destiny and yanked them in his wake.

Suddenly they were heading back to her hotel together, Pipín anxious to atone for his blunder.

Suddenly they were in her bed.

Suddenly the blonde jazz singer was packing the next day and leaving Pipín's hotel suite in a huff, and Audrey found herself in the woman's place.

Suddenly she was on his boat a day later, kissing him after a training dive, when he bolted overboard—the safety diver whom he'd just met and hired, Massimo Berttoni, hadn't resurfaced after going down to retrieve the sled.

Suddenly she was staring at death, handling it with more calm than anyone in his crew.

Suddenly she was at the dead man's post, with Pipín's life in her hands: She was his new safety diver at 197 feet.

Suddenly she was on the phone, calling her parents in Mexico City to ask them to retrieve her furniture and dog and clothes and car from her apartment because she'd decided to drop out of college and fly to Miami to live with her thesis subject, and her shell-shocked parents were jumping on a plane to Cabo to see if she'd come down with typhoid fever again, or something worse, and when they arrived and asked this man Pipín what the mad rush was, he replied, "I don't live by a compass.

I go with the wind.

If I don't take her with me, it will be painful, but I know I won't come back for her.

The magic is right here.

Right now.

You can't kill the magic and bring it back to life."

Then he popped a world-record 429-foot dive and they flew away together.

How long could they last before one of them came up for air?

He believed that he'd been selected to go on a quest by an undersea god.

"People have always told me that God lives in heaven," he wrote in a book.

"Yet, as much as I have tried, I have never been able to see him.

I have seen that other God, the one that lives down in the deepest blue of the submarine abyss, where I descend. He gave me the mission of showing all humans how to discover their aquatic potential. He gave me the skills to descend at ease into his realm of darkness, where he always shows his face as pure light."

It was one thing to take the plunge with such a man.

Two wives and a slew of girlfriends had, but none had gone down far enough, and none had stayed under.

He became disillusioned, or in need of someone else's touch to soothe his restless, lonely heart.

His eye would stray.

Once he awakened soaked in rubbing alcohol beside a girlfriend, her eyes ablaze as she held a lighter over him and screamed, "Who is she? Tell me now!"

Now it was Audrey waking up beside a man whose moods shifted faster than sky over ocean, a generous man who could make sudden friends—or enemies—for life.

Who had to beat Italian rival Umberto Pelizzari's new record by 13 meters, right now, if Pelizzari had just beaten his by 12.

A man who...wait a minute.

Had she really seen what she thought she'd seen just before bedtime?

A man who turned to his Santeria gods for guidance, summoning them with honey and cigar smoke and herbs and branches and bones and scraps of coconut shell, and a funny sort of song?

She got out of bed at dawn and headed to the kitchen.

Coffee for Pipín.

Coffee and fruit for the little statue of one of his gods when Pipín wasn't around to make the offering.

She accommodated his myth: the knight on the underwater god's mission.

She could even turn a blind eye to his wandering eye.

Their hands compulsively touched when they walked or sat.

They were each other turned inside out, two souls melding parts to produce a whole: I'll take us around theworld.

You'll see and do things beyond your dreams.

I'll live in the tunnel.

You'll order out for reality and a side of perspective.

I'll exaggerate, tell the world that I achieved a record dive "with absolute self-control and an unyielding faith" thanks to a state of concentration in which "electric energy, magnetic energy and all the forces of nature converge to increase my biological capabilities."

I'll make the cash flow.

You'll keep the checkbook.

I'll teach you to seize today.

You'll remember my two promises yesterday and three appointments tomorrow.

I'll dream up the world's deepest dive tank with a domed underwater disco where scuba dancers boogie in leaded, magnetized shoes.

You'll find the shoemaker.

"She could find solutions just by looking in my eyes," Pipín would say.

"I thought I'd go from girl to girl the rest of my life, because even the ones who were scuba divers had other priorities.

Sooner or later the woman would ask, 'Why is your mind always there?' But not Audrey."

The magic kept coming.

Three weeks after they fell in love, they were freediving with dolphins off the coast of Honduras in front of cameras for his new Mexican TV series, then with sea lions off the Galapagos and with humpback whales off the Dominican Republic.

Well, at least she was.

He watched in astonishment as the 45-ton whales cavorted with her in a watery waltz, then in vexation as they flinched from him—as if they sensed that she was the one who cried when shrimp died in the aquarium, the one who studied and sketched fish.

.

.and he was the one who speared them.

She shed the air tank, bubbles and noise.

She became the mermaid.

Her drawings ripened.

In one that she titled Pleasure Shared, she was naked, her hair fanning in the water, her back arched in abandon, her legs splayed beneath a shark.

A cloud hung over her enchantment, a gnawing fear: He feared nothing—not in the water.

Standard diving protocol?

At any moment the man she loved could die.

"I've seen world championship divers, and I've seen him," photographer and scuba diver Ron Everdij would say, "and they are not like him.

It's like the difference between runners from Kenya and runners from the rest of the world.

But one day he'll go wrong.

He thinks he's invincible.

He's like one of those people who's arrested for shoplifting and goes right back to the same store the next day."

Lying still in a swimming pool practicing apnea, the suspension of breathing, he could last more than seven minutes.

But the pressure, both physical and mental, where he went—where World War II submarines would creak and groan—sliced that time in half.

She watched him on their backyard patio on the waterway at the edge of Miami Beach as he prepared himself for this, pounding out stomach crunches and bench presses while he held his breath for one minute...two...2:30...and counted the contractions that rippled his diaphragm as his body screamed for air.

He'd keep going—2:45...2:50—everything around him melting into gray soup, and it was only by the little trick he'd discovered, focusing on the fading backyard fence and the tall building beyond it and compelling them to return to their perpendicularity, that he could reach his record of 45 contractions, that he could hang on for just a few...ticks...more.

But sometimes, in the ocean, he miscalculated.

He'd blacked out by descending too swiftly; or too slowly, when currents swept the cable off a vertical line; or too soon, before he'd recuperated from a previous dive.

Sometimes his equipment malfunctioned.

His cable had snapped.

Many times his sled had gotten stuck, and once it had pile-driven him into knee-high mud 377 feet below.

He'd been partially paralyzed for a half hour after he pinched his nostrils and blew so hard, trying to equalize, that air leaked into his brain.

He'd died three times during No Limits dives, he said, convinced that Olokun, the Santeria undersea god, had brought him back to life each time in a bath of white light.

He'd suffered so many decompression hits when he went under on scuba tanks that a neurologist had warned him never to touch a tank again.

Audrey, watching him strap another one on anyway, wondered if she should take a knife and slash the hoses.

He often wouldn't bother to use Trimix—the combination of nitrogen, helium and oxygen that scuba divers are cautioned to use in place of compressed air at depths greater than 125 feet—or to slow down for the two-or three-hour ascents sometimes necessary to avoid the bends.

His elbow and leg would begin to itch when he surfaced, a sign that nitrogen bubbles were trapped in his veins or his bones and that one day the bones might begin to snap like pencils.

Keep going deeper, his friends warned him, and you'll end up in a coffin, Pipín, if you're lucky.

A wheelchair, Pipín, if you're not.

But he'd scoff, even as he neared 40 and the blackouts multiplied.

Audrey would push away his panicking crew when he surfaced unconscious, open his airway and blow on the skin around his mouth to stimulate his reflex to breathe, Pipín, breathe!

She had to go deeper.

It was the only way to understand him.

She had to kiss him goodbye, when Cuban authorities forbade him to return, and fly to his homeland alone to trace his life.

She had to stand on the cliff overhanging Matanzas Bay—his backyard—and picture Francisco Ferreras, poised here in front of the boys who stared and sneered at him, about to take his first risk.

It was 1969.

He was seven.

The boy who had found it so difficult to walk because his metatarsals were malformed and his feet jutted inward, was about to start running.

The child who was mute until he finally uttered "pi-pin...pi-pin"—no, not a word, but close enough to celebrate and to turn into his nickname for life—was about to leave them all speechless.

The trapped boy was about to spring free.

He peered down at the water.

None of the kids gathered about him would dare this.

But no one was there to stop him.

Not his uncle, Dr. Panchin Guerra, who'd prescribed water therapy to trigger the boy's dormant motor skills and had been astounded when the child began to swim before he could walk.

Not Haydee, the big-hipped black servant who was sure the Santeria ritual she'd snuck the boy off to had done the trick, the throbbing drums and animal sacrifices that had summoned Olokun, the old African god of the undersea and of good health, to cure the child.

Not Pipín's father, who'd never lived with him in the big walled estate on the cliff and who'd soon be divorced from Pipín's mother.

Not the mother herself, who left the house to work in Cuba's agriculture ministry each morning before Pipín woke up and didn't return until after he fell asleep—seven days a week.

Pipín took a deep breath.

Then the boy with the orthopedic shoes and eyeglasses and rasping asthma flew off the cliff and plunged into the sea.

The other children scanned the water in astonishment, then fear: Where was he?

Audrey entered the cave with her video camera.

Here he'd sat, in a space as big as a living room with a foot of air to breathe between the ceiling and the water's surface, relishing the thought of them all up there panicking, ashamed of themselves for all the shame they'd made him feel.

Here he'd sat, filling the cave with his imagination and loneliness.

At peace for once.

It was like being in the trap again, cut off from the world and scarcely able to move, only it was a beautiful trap because he had contrived it.

A beautiful aloneness because he'd arranged it.

But it was such brief magic.

Because soon after he dived and made the world go away, his world went away from him.

The grandmother, uncle and aunts who'd helped raise him fled Fidel Castro's regime for Florida.

The servants who mothered him and introduced him to the old African gods were dispersed.

He was placed in a boarding school that specialized in sports training so that he might pursue his proclivity for swimming.

He returned to the underwater cave on weekends and in the summers, clutching a plastic bag of fruit so he could stay inside his lair longer and make loneliness lovelier still.

But he needed to enlarge his kingdom.

He forged a mask by heating the rubber from Soviet boots and pressing two ovals of glass into it.

He fashioned fins by cutting swaths from plastic boxes of frozen fish and binding them with screws filched from window frames.

He rigged a speargun from a piece of pipe and elastic bands.

He hardened his determination and deltoids by swimming laps for four hours a day at boarding school, where he was developing into one of Cuba's top junior swimmers, and in truth, just finding a way to exhaust his anxiety so he could sleep.

By 13 his asthma and orthopedic shoes were gone, and so was his mother—she had moved to Mexico City for four years to serve as first secretary to the Cuban ambassador.

Pipín's domain grew wider still.

Down he went after the big groupers and snappers lurking in the deep water.

He learned to imitate their movements, to intuit their intentions, to stalk them in the dark caves they darted into to evade him.

He became a shark.

"For me, sharks aren't monsters, but partners," he'd say.

"In my imagination I become one of them."

He emerged from the sea and tried to fit into the world of the two-legged land creatures.

He scraped by in school until his final year, when he and his classmates were ordered to harvest sugarcane on a weekend when he'd planned another spearfishing expedition.

Why am I learning math or history?

The only history I want to know is my history.

I go underwater to feel a pleasure greater than any that life on land has to offer me.

It is better than sex.

He refused to join the harvest and was expelled.

His mother sobbed.

The boy was trapped again.

She was about to return to Cuba to become a university professor.

His father was a judge.

They'd both fought in the revolution and been decorated as heroes.

How could their dropout son earn love and admiration?

In the working world, possibly?

In marriage, maybe?

It ended in a year and a half.

An Italian diving journalist on holiday in Havana saw how deep the 19-year-old Pipín could dive and hurried him to Cuban authorities, urging them to let the boy travel overseas and break the world record.

They yawned.

They'd never heard of such a sport.

For six years they yawned as Pipín pestered them.

Then came his moment.

Cuba, unveiling a seaside resort in Cayo Largo in 1987, invited a group of international underwater photojournalists to publicize it.

Sure, why not let that crazy fish man entertain them?

He scurried about the resort, a charming nobody promising photographers the chance to document the deepest dive ever without the aid of apparatus.

Here, at last, was a chance to show his parents and everyone else.

Damned if he didn't—67 meters, 220 feet!—and if the photojournalists didn't send dispatches around the world.

He was on fire now, lusting for bigger, deeper, farther, more.

He busted the world record again a year later with a 226-foot dive.

He knew his limit was his anxious heart, his teeming brain.

He studied controlled breathing techniques with a Hindu yogi.

When he consulted Buddhist monks they told him, Learn to wait.

Learn to wait?

Suddenly a yacht ornament for Cuban generals and politicians on fishing trips.

Suddenly signing a sponsorship deal with Europe's largest diving equipment company, marrying an Italian beauty, hosting an Italian TV travel show.

Suddenly, in 1991, chalking up a world-record 377-foot No Limits dive, the first ever televised live in Europe...but still sure that his mother was unimpressed.

Suddenly watching his second marriage go up in smoke, then two of his high-placed friends in the Cuban military getting executed for drug trafficking.

Suddenly sweating bullets because they were his two buffers in a regime that could turn on him at any moment for the six cars and three houses he'd finagled with his new fame and riches.

Suddenly stepping onto a friend's private plane in the Bahamas in 1993 and severing one more connection—to his homeland, his parents, his separated wife and three-year-old daughter—and defecting to the U.S.

When Audrey had heard all the stories and visited all his old diving haunts, she flew back to him in Florida.

Full of wonder that she'd been granted entrance into hisworld, the one he'd created against all odds.

Full of wondering: for how long?

Death crept closer.

It found them again in Cabo San Lucas, of all places, where Pipín and Audrey had returned to reclaim Pipín's world record, to dip once more in the water where magic, eight months earlier, had struck.

Pepe's body surfaced instead.

This wasn't like losing Berttoni, a stranger added as a safety diver on the fly.

Pepe had been Pipín's fun-loving pal since they were teenagers in Cuba, his crew chief, the safety diver at the bottom, the only one deeper than Audrey—the man who'd introduced her to the king.

Oh, God, if only Jacques Mayol and Enzo Maiorca could've lived with the limits.

If only the Frenchman and the Italian hadn't devised weighted sleds sliding down cables to smash the depth barriers in the '60s and '70s, Pipín's quest could've remained simple and pure, and nobody would've had to die.

He might never have known the adrenaline rush of No Limits, never reached depths that were perilous even to men on tanks, depths that required all that equipment that could break and all those safety divers who could die.

But what had killed Pepe?

But the whispers soon began: that Pipín was cutting corners, that both Pepe and Berttoni might have died because they descended to unsafe depths the way their leader routinely did, breathing from a tank of compressed air instead of Trimix.

Nightmares wracked Pipín.

He knew this second death of a crew member would be turned against him.

He'd just broken with yet another institution—freediving's mainstream sanctioning body, AIDA—because his rival Pelizzari was behind it and because of his disagreement over some of the safety procedures that AIDA requires for certification of record dives.

Pipín had just formed the International Association of Freediving (IAFD) despite howls that it was a dangerous conflict of interest for a man to act as his own sanctioning authority on a record attempt.

But Pipín had seen Pepe go that deep without Trimix plenty of times, so that couldn't have caused his death, he insisted, and besides, in Pipín's world a man died because God decided it was his time.

Audrey and the crew turned to Pipín.

Well?

Pipín turned to Audrey.

She was the person he loved and trusted most, so it only made sense to ask her: When he dived, would she go one rung deeper and take Pepe's place?

She would.

She did.

He set another world record.

But it wasn't deep enough.

Could Audrey take the next step?

After all, it was better than sex.

She was better than the young woman he was training on the sled.

Besides, didn't it seem safer to be the diver on the sled than the diver saving the diver on the sled?

She didn't think long.

Sure, she'd try it.

Not for his reasons.

Not to be singular, not to be separate—there wasn't a competitive bone in her body.

To connect.

With him.

To inhabit his world completely.

Wasn't it all or nothing with this man?

I thought that if I could enter his underwater world, I could be closer to him."

She began to train.

He began to order her food when they went out to dinner.

She led Pipín to their backyard Jacuzzi in 1997 and astonished him by lasting five minutes and 50 seconds submerged—a half minute longer than the female static apnea world record.

They headed to the Cayman Islands for her maiden voyage, but suddenly Pipín, ascending from a scuba dive just minutes after a No Limits training dive, was losing consciousness on the boat, hitting his head, vomiting and shaking from a violent seizure.

She found herself on an airplane back to Miami, sitting in a hospital room watching him twitch and slur for three days, then rise and walk out against doctors' advice, saying it was time to fly back to the Caymans and make their dives.

With Pipín every accident became a reason to continue, every death a debt that could be repaid only by carrying on—never a signal to reassess, to slow down.

Audrey nailed her 263-foot dive a few days later, and bingo, she was the French female record holder.

She loved it.

Everything went away on a No Limits dive.

Your worries.

The world.

Even your body.

"You forget you have one," she told a reporter for deeperblue.net, "and that is when you meet the other person who lives inside you, the one in control of everything: your mind." A year later, in 1998, she joined Pipín for a 378-foot tandem dive in Cabo San Lucas, and they were the deepest-diving duo ever.

They married in '99.

A glance, that was all they'd have to exchange in the water now, and each would know exactly what the other meant.

She became the deepest female diver ever with a 412 1/2-foot plunge off the Canary Islands in 2000, surviving an 18-second fright when her sled got stuck at the bottom and safety diver Pascal Bernabe helped free her.

She encored with a 427-footer off Fort Lauderdale a year later, extending her women's record and making her the fifth-deepest diver, of either sex, ever.

She was the diver squeezing six workouts into a week while he blew off three.

The one who could withstand 90 diaphragm contractions to his 45, could rev her heart rate to 200 while his max was 160.

Who was unflappable even when Pipín ambushed her during training dives, springing out of nowhere at 375 feet to snatch her and test her composure.

Who could read Egyptian history 20 minutes before a record dive while he couldn't absorb a letter from his mother for the two weeks before one of his.

"It made me feel ashamed," he admitted.

"How could she do that? She has the stronger mind. A perfect mind. I took her as a student, and she became the teacher."

Then came the audacity.

Tanya Streeter of the Cayman Islands unfurled a 525-footer in August 2002, nearly 100 feet beyond Audrey's record dive.

In the factionalizedfreediving universe, full of strife and ego, Streeter's record triggered more strife, more ego.

AIDA anointed Streeter's dive the new world record for both sexes because she'd achieved it using AIDA's judging protocol and safety standards.

Pipín's IAFD insisted, of course, that Pipín's dive of 531 1/2 feet in 2000 remained the record.

To reclaim the female world record, Audrey would have to creep perilously close to Pipín's 531 1/2-foot IAFD record.

Or...past it.

Imagine that.

Audrey taking Pipín's record.

Her eyebrows jumped when Carlos Serra, Pipín's IAFD vice president, teased her about it.

Her eyes went wide.

"Don't say that," she pleaded.

"Don't let him hear that. Don't even think that."

Well...could she?

Pipín turned to Audrey.

Was she ready to go that deep?

She was 28.

She wanted to have children with him, but she knew that when she did, she'd have to turn and head back up to the surface.

She looked in his eyes.

She was like an old-fashioned French wife who'd muck the barn and pluck the grapes beside her man.

She understood that world records were the family crop, the product that attracted the sponsorships and media and enrollment in their freediving courses, the TV and movie opportunities that sent them on adventures across the seven seas.

She nodded.

She'd go deeper.

But how much deeper?

Five-hundred twenty-eight feet, decided Pipín, 161 meters.

That would be the target for Audrey's dive last Oct.

12 off the Dominican Republic.

Three feet more than Streeter's record.

Three and a half feet less than Pipín's.

Audrey nodded.

Pipín changed his mind.

Why not 531 1/2?

No, wait, said Pipín.

Make it 538 feet—164 meters.

Audrey was stunned.

He wanted her to beat his record.

Maybe because, where he'd gone all his life to separate, he'd finally connected.

Maybe this was his gift to her.

Scratch that.

She might as well go for 544 1/2.

After all, they'd just arrived in the Dominican Republic, and she was nailing these depths in training so easily.

After all, didn't every extra foot she went using his techniques—a woman with scant athletic background and just five years of freediving experience—jam another foot in the mouth of his critics and rivals?

Hold on.

How about 551 feet?

Maybe because he was certain he could dive deeper.

O.K., then, we'll make it 558, a nice, round 170 meters.

That was the depth she reached on her final training dive—unofficially the deepest in history—and then climbed back into the boat looking fine, admitting only later to safety diver Matt Briseno that she felt "weird."

Well, then, enthused Pipín, let's go for 597 feet—182 meters—and no, that wouldn't create an even riskier gap in their already overstretched chain of safety divers, see, because Pipín could leave his supervising post at the surface, don scuba tanks and become the bottom diver at 597, and then, on his next dive, could score that nice fat number still looming: 600.

Serra, in charge of the dive logistics, was aghast.

"Do you want to dig a hole and go through the planet to China?" he cried.

Pipín turned to Audrey.

She'd watched him do the riskiest things and said nothing, but the thought of her husband at so extreme a depth on scuba tanks, after everything doctors had warned, made her finally dig in.

No, Pipín, she said.

She'd protect him.

She'd go 561 feet, 36 less than he wanted, but still the deepest a human being had ever gone.

But he'd have to wait for her at the top.

Black fists clenched on the horizon that morning, then ripped across the sky hurling wind and thunder and lightning.

They blew open the door to the closet in Pipín's mind where all the magic lives, and out stepped Chango, the Santeria god of storms.

This had to be a sign from Chango, Pipín thought, a command to cancel the dive.

But 15 boats waited to take on spectators and reporters and cameramen for the Ocean Women movie.

At mid-afternoon, when the storm relented, the dive was on.

Audrey read about the pharaohs as Pipín did the final equipment check, a duty he usually shared with his crew.

But they'd angered him by placing two decoupling devices on the sled backward during training dives, so he shooed them away.

He opened the valve to make sure there was air in the tank that would inflate the lift bag and bring her back up.

He shut it when he heard the hiss of air, but he didn't check the pressure with a gauge.

He tied a strip of red cloth around her wrist.

Chango's color.

He peeled a banana and dropped the skin in the sea for Olokun.

She smiled and entered the water in a yellow-and-black wet suit.

Gray skies.

Slight chop, maybe a foot.

She and Pipín had both dived in much worse.

She ventilated as Serra barked the five-minute countdown.

Then she took her final breath of air, and vanished.

"F---, f---, f---," Pipín began murmuring.

"What's wrong?" asked Serra, studying two watches.

"Why is she going so slow?" he demanded.

Serra felt the cable shudder.

She'd struck bottom at 1:42...14 seconds faster than she took during her training dive three days before.

"Relax," he said.

Now all Audrey had to do was pull the pin that released the ascent portion of the sled, open the valve on the air tank and hang on for dear life as it carried her back to air, applause and Pipín's embrace.

She turned the valve to release the 3,000 pounds per square inch of air compressed inside the tank.

The bag didn't inflate.

She didn't budge.

Again she turned the valve.

The sled still didn't rise.

What was happening?

A half minute had passed.

An eternity at such depth.

Oxygen dwindling.

More than 200 pounds of pressure per square inch leaning on her body.

Pascal Bernabe, the bottom safety diver, Audrey's dear friend, inserted his mouthpiece into the lift bag to add air.

The sled began to lift...but not enough, not enough.

She remained 538 feet below.

A minute since she'd hit bottom.

Why?

Because neither was looking at a watch.

Because she still appeared so calm.

Because they'd unjammed the sled at the bottom and salvaged her record dive off the Canary Islands.

Because she'd never taken air from a tank at such depth, and many experts believed that doing so would cause spasmodic coughing—and drowning—or make the lungs expand and explode on the ascent.

Because, perhaps, she was too narked to realize the danger.

Because, maybe, the first breath she took from Pascal's air supply would render this dive a failure, a disappointment to all those waiting above.

Because, as soft as Audrey was with shrimp and whales and human beings, that was how hard she was on herself.

A perfectionist.

A soldier with a duty.

And she'd told Pascal, more than once, that he was notto give her air unless she signaled for it.

But, goddammit, Pipín would flog himself later, she would've taken air if it had been him holding the mouthpiece to her lips, him stationed at the bottom, the way he'd wanted.

Pascal dipped beneath the sled, pushed it and watched it finally creep upward.

Upward into a vast stretch of unmanned ocean: 260 feet of it between her and the next safety diver.

No Cedric Darolles at his old post—394 feet—where he'd been stationed on Pipín's and Audrey's recent dives.

He was dead, perished the year before while cave-diving, and Pipín hadn't replaced him.

It was there, three minutes and 50 seconds into the dive, that Audrey lost consciousness and drifted away from the cable.

Above, Pipín was already in a frenzy over the time elapsed, slinging on a scuba tank, diving.

Below, Audrey sagged into Pascal's arms as he ascended beneath her.

Pascal couldn't do what his heart screamed to do.

Couldn't rush her to the top or he'd die from a massive decompression hit, and there'd be two death certificates for sure.

His heart pounded.

Panic could kill him too.

Two minutes.

That's how long a diver who lost consciousness underwater had to live.

He carried her to the next diver up, employing the relay system designed to prevent any safety diver from ascending too far too fast and dying from the bends.

He rose twice as fast as a scuba diver should.

It still took a minute and 55 seconds to get her to 295 feet, where safety diver Wiky Orjales awaited.

No, he didn't.

Oh, God....

So much time had elapsed that Wiky—who was on a very short time leash because he was breathing compressed air instead of the Trimix that Pascal was inhaling—figured the dive had been aborted, that Audrey had to be below sharing Pascal's mouthpiece.

So he'd ascended.

And so in Wiky's place Pascal found nothing but more ocean.

Now Pascal had to wait to avoid the bends, 63 agonizing seconds until Pipín appeared in an explosion of bubbles.

Pascal handed him his wife.

Pipín rose, taking another decompression hit himself, bloody foam pouring from Audrey's mouth.

Eight minutes and 38 seconds after her last breath, he surfaced with her body.

She still had a pulse! He clamped his mouth on hers and tried to fill her with his breath, then Serra and the eight-man rescue patrol that the IAFD had hired took over.

Serra looked in her eyes.

He knew that the pulse was a lie, that her brain was dead.

It was all a blur after that.

The motorboat dash to shore, the hopeless race to the hotel infirmary and then to the hospital.

Pipín sitting in the hotel lobby afterward, lost somewhere deep inside his motionless body, his face frighteningly composed.

"He seemed like a man executing a plan he'd downloaded into his memory for just such an occasion," Paul Kotik, a deeperblue.net journalist and diver, would say.

"When we parted, I didn't think I'd see him alive again."

The funeral procession motored a few miles east of Miami Beach, then surrounded Pipín's boat, Olokun.

He slipped into the water with a beige marble urn and, with remarkable poise, poured her cinders into the sea.

Then he went home and sobbed until days turned into weeks.

How does a man grieve while the world's screaming in his ears?

Why were there so few safety divers, Pipín?

Why, Pipín, wasn't Audrey wearing a self-inflating wet suit that she could've activated to jettison herself to safety, as other No Limits divers used, or a harness-and-pulley system that could've cranked her up from above?

Why no deaths in other divers' No Limits record attempts, Pipín?

He couldn't eat.

Twenty-two pounds melted away.

He couldn't sleep.

He couldn't work.

He couldn't process the report from Kim McCoy—the oceanographer who provided the IAFD with computerized readings of its dives—that listed all the factors that might have contributed to the sled's malfunction: a cracked Teflon bushing; a pair of wings that were designed to stabilize a camera but that created a lateral force on the line; a new cable and bottom weight that turned out to be more prone to create a pendulum effect on the cable; and the possibility that the air tank wasn't full.

Pipín filed a lawsuit against Ricardo Hernandez, a former IAFD employee leading the chorus of charges, for infliction of emotional distress, invasion of privacy and defamation.

Hernandez filed a counterclaim, recently dismissed, alleging that Pipín had fired him unfairly two years ago and that this had sent him into a psychiatrist's care.

Why, Pipín kept wondering, couldn't they all just say what Audrey's mother, Anne-Marie, did: that no one was to blame, that the sea wanted her forever?

For once in his life, Pipín couldn't even go into the ocean.

He knew with terrifying certainty that no woman—even one he turned to for comfort in his grief—would ever go that deep with him again.

When it became more than he could bear, he went to his Santeria shrine and summoned Olokun.

Couldn't he just end it all, he asked, and join her?

He packed all the statues and amulets from the shrine into a bag, boarded his boat and traveled for four hours.

He cast everything into 10,000 feet of water.

He went home and lay on a table for four hours more while a tattoo artist inscribed the image of the half-naked woman inside the hammerhead shark on his calf.

He replaced Olokun with Audrey.

She became the one he spoke to each day, the one he asked for blessing and guidance.

She'll be down there, he's certain, when he makes his planned world-record dive in mid-July, at precisely the coordinates where nine months earlier he turned the green water gray with his wife's ashes.

He'll attempt 558 feet, equaling the depth of her final training dive, which he declared the new IAFD world record after her death.

It's a dive that he says he must make, one that frightens his friends and that helped convince IAFD vice president Carlos Serra to part ways with him early this month.

When it's all done, you'll have to decide which side of the water's surface to see the myth through, and who got the moral of the story right.

Those who see the half-naked woman inside the hammerhead shark and say, "Of course, because that's where she lives now."

Links :

- Deeper Blue : IAFD/McCoy Report On Audrey Mestre’s Death

Monday, January 11, 2021

AI and satellite data find thousands of fishing boats that could be using forced labor

From The Conversation by Gavin McDonald

Fishing on the high seas is a bit of a mystery, economically speaking.

I am an environmental data scientist who leverages data and analytical techniques to answer critical questions about natural resource management.

Yet fishers continue to harvest on the high seas in staggering numbers, suggesting that this activity is being financially supported beyond just government subsidies.

Forced labor is a known problem in open ocean fishing, but the scale has been very hard to track historically.

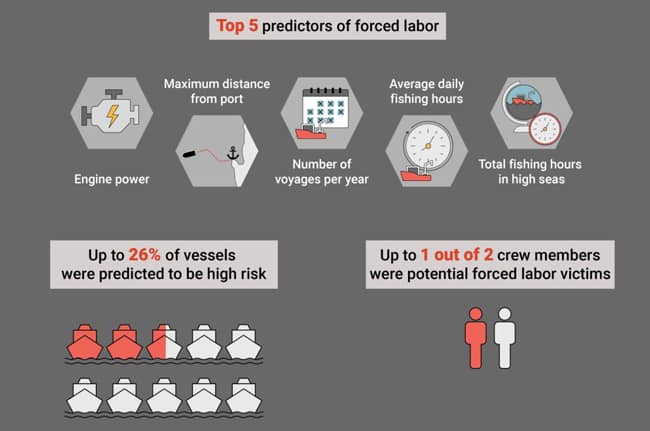

By combining our team’s data science expertise with satellite monitoring, input from human rights practitioners, and machine learning algorithms, we developed a way to predict if a fishing vessel was at high risk of using forced labor.

Forced labor is defined by the International Labour Organization as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered themself voluntarily.”

Our team wanted to say more about how forced labor is being used in fisheries, and the breakthrough came once we asked a key question that drove this project:

To answer this, we first looked at 22 vessels known to have used forced labor.

This list of indicators included vessel behaviors like spending more time on the high seas, traveling farther from ports than other vessels and fishing more hours per day than other boats.

Now that we had a good idea of the “risky” behaviors that signal the potential use of forced labor, our team, with the help of Google data scientists, used machine learning techniques to look for similar behavioral patterns in thousands of other vessels.

Shockingly widespread

We examined 16,000 fishing vessels using data from 2012 to 2018. Between 14% and 26% of those boats showed suspicious behavior that suggests a high likelihood that they are exploiting forced labor. This means that in those six years, as many as 100,000 people may have been victims of forced labor. We don’t know whether those boats are still active or how many high-risk vessels there may be on the seas today.

Squid jiggers lure their catch to the surface at night using bright lights; longliner boats trail a line with baited hooks; and trawlers pull fishing nets through the water behind them.

Another key finding from our study is that forced labor violations are likely occurring in all major ocean basins, both on the high seas and within national jurisdictions.

As it stands now, our model is a proof of concept that still needs to be tested in the real world.

Turning data into action

Our team has built a predictive model that can identify vessels that are at high risk for engaging in forced labor.

As we get more substantial data and improve the accuracy of the model, we hope that it can eventually be used to liberate victims of forced labor in fisheries, improve work conditions, and help prevent human rights abuses from occurring in the first place.

We’re now working with Global Fishing Watch to identify partners across governments, enforcement agencies, and labor groups that can use our results to more effectively target vessel inspections.

%20(1).png)