Near the community of Selsey, England, saltwater marsh and other coastal ecosystems have been allowed to reclaim what was farmland and is now known as the Medmerry Nature Reserve.

Photo by Gillian Pullinger/Alamy Stock Photo

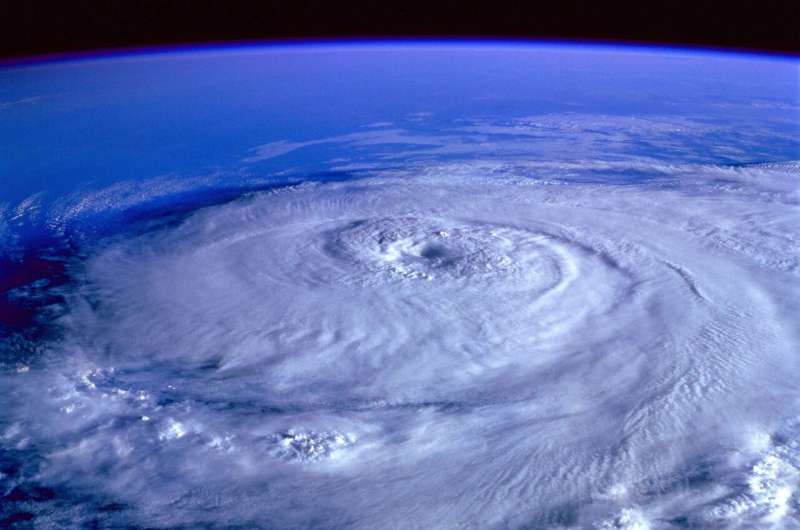

From HakaiMagazine by Erica Gies Welcome to Selsey, a community that welcomed back the marsh. As climate-fueled floods and droughts wreak havoc around the world, a hard truth is emerging: sooner or later, water always wins.

But these devastating water extremes are not just due to climate change.

They are made much worse by our poor development choices aimed at controlling water.

The following excerpt is from the book

Water Always Wins, in which Hakai contributor Erica Gies follows innovators in what she calls the Slow Water movement who are instead asking a revolutionary question: what does water want?

What water wants is to reclaim its slow phases—wetlands, floodplains, mangrove forests—that we’ve erased with development.

The Slow Water movement has parallels to Slow Food, drawing attention to water’s relationships with rocks, microbes, beavers, humans, and how our actions affect them.

Projects work with local geology, life, climate, and cultures rather than trying to control them.

On May 10, a four-bedroom house perched on the beach of a North Carolina barrier island in the town of Rodanthe collapsed into the ocean.

It was not the victim of a violent hurricane strike or storm surge.

Rather, a low-pressure system coupled with a high tide drew ocean waves onto the shoreline, leaving heaps of sand on the prophetically named Ocean Drive.

Then—in that viral video moment—the water gently pulled the house loose and set it to bob upon the sea.

It was not the first house—this year! that day!—nor will it be the last.

This is reality in the 21st century.

By 2100, high tides will likely inundate land that’s home to between 190 and 630 million people worldwide.

The range depends on whether humanity slashes carbon emissions by midcentury or, instead, continues to fail.

There is no longer any question that water is moving in and people must begin to move out.

For that homeowner in Rodanthe, water has dictated immediate retreat from the coastline.

Elsewhere around the world, people are beginning to leave coasts, usually on the heels of disasters or when they can no longer afford routine flooding or salt intrusion that fouls drinking water, kills plants, and spreads sewage.

But now scientists and government agencies are calling for a more deliberate, organized—and, in the long run, much cheaper—pullback.

It’s called strategic or managed retreat because it’s planned, as opposed to crisis driven.

It relinquishes the idea of control, of “holding the line,” in favor of accepting nature’s power and giving those protective ecosystems space to absorb wave energy and tides.

A home in Rodanthe, North Carolina, succumbs to the sea on May 10, 2022.

Photo by Cape Hatteras National Seashore

After decades of resistance to the idea, which detractors characterized as “giving up,” some communities are embracing it.

Today, managed retreat driven by pragmatism is an increasingly accepted component of government policies.

One of the most ambitious programs is in the United Kingdom, which is planning a countrywide step back from the sea.

With its thousands of kilometers of coastline exposed to the rough North Atlantic Ocean, the United Kingdom is mapping out where it will cease trying to hold back the sea within a decade or two.

And in other places around the world, new amphibious designs embrace a way to live with water without courting regular disaster.

Both managed retreat and amphibious housing are the ultimate expression of Slow Water thinking, of accepting and working within what water wants.

The UK program, called coastal realignment, has large stretches of coast in its sights.

In England alone, the government has identified 1.8 million properties at risk of coastal flooding and erosion by 2080, along with £120–£150-billion (US $169–$212-billion) worth of infrastructure such as roads, schools, and railways.

The UK Environment Agency is acknowledging that it cannot win a war against the sea, even if it could afford to wall off the whole coast—which it can’t.

Accepting that reality includes strategies such as abandoning or removing hard-barrier coastal protections—generally, sea walls or embankments of big rocks—in places where they must be maintained constantly and still sometimes fail.

Instead, the agency is suggesting that people move back from threatened coastlines.

One strategy is to build new barriers against the sea farther inland and allow marshes, estuaries, and other coastal habitats to migrate into the breach.

Because the new barriers are buffered by natural ecosystems that dissipate wave energy and reduce erosion and flooding, they are less expensive to maintain and less likely to be undermined.

Most planned projects are in areas of low human density, such as marginal farmland, rather than urban zones.

But depending on the location, the scale, and the physics, these areas can reduce impacts on nearby urban areas.

Several such projects have already been built in the United Kingdom.

On a cold, bright day in early March 2020, I drive to the sea.

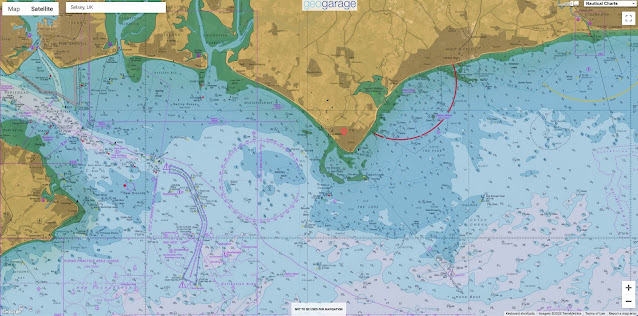

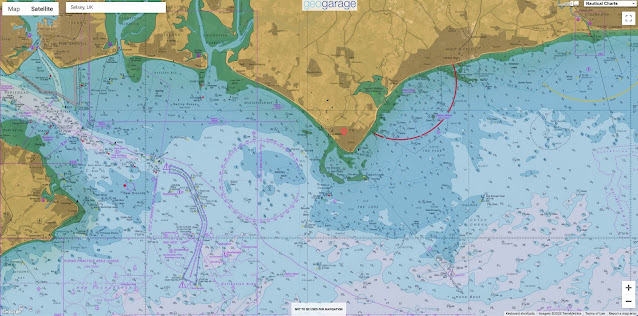

I want to see the Medmerry Managed Realignment Scheme, the largest planned retreat on an open coast in Europe at the time it was completed in 2013.

Now it is a nature reserve administered by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

Two hours southwest of London is Selsey, a town of about 10,000 people in south Sussex that lies on a peninsula called Manhood.

(Yes, really, but it derives from Man wode—“wood”—and refers to a long-gone communal forest.) Selsey lies at the tip of the peninsula, poking its nose out into the English Channel.

The west side of the nose is home to the post-realignment Medmerry Nature Reserve.

Selsey is a typical English seaside town with pubs, charity shops, and grocery stores lining the quiet high street.

Low lying and historically riven by estuaries and rifes (a local word for creeks), Selsey was, in fact, an island prior to about 1750.

Residents accepted the town’s tidal separations until about 200 years ago, when the lord of the manor decided he didn’t like getting a ferry across the marshes and wanted greater profits.

So he drained the land, reclaimed it from the sea, and turned it into farmland.

Now there’s just one road in and out of town, via a bridge over an inlet called “the ferry channel,” where the boat used to take people across at flood tide.

The town of Selsey, on a peninsula called Manhood in England, was an island or peninsula at various times in history, and has often contended with flooding.

In the far distance, behind the town, lies Medmerry Nature Reserve.

Photo by Geoffrey Deadman/Alamy Stock Photo

Although Selsey lies within the uneasy embrace of the sea, humans have lived here as far back as the Stone Age.

The town was once the capital of the Kingdom of the South Saxons, and its name, meaning “seal’s eye,” or “isle,” is derived from the Saxon language.

Pete Hughes, an ecologist with the nearby Chichester Harbour Conservancy and a consultant on the Medmerry project, tells me that “a huge amount of archaeology was discovered” during the managed realignment project.

The range of findings speaks to how the geography here has changed over the centuries, illustrating how many of the landscapes we think of as fixed are ever in motion.

Archaeologists found a submerged oak forest from Neolithic times (2455–2290 BCE), now visible at low tide.

They also discovered an Iron Age (760–410 BCE) human skull held by a rock, its spinal column trailing out in the water behind.

More recent artifacts from about 500 years ago show how fundamental the sea has been to human life: fish traps, an eel basket, shrimp and prawn traps.

Archaeologists also found two water wells—signs that fresh water was once available where the sea now pulses.

The name Medmerry comes from a small village that disappeared into the sea a few hundred years ago.

“It was built on marshes,” explains David Rusbridge, whose family farmed on the Manhood Peninsula for 400 years.

Medmerry means “middle eye (isle)” because it too was once an island, as revealed on a 1752 map.

A neighboring hamlet, East Thorney, was also lost to the sea, possibly done in by 19th-century drainage ditches to move water out of the marshes.

Without those marshes as protection, the sea moved in around 1900.

Now the coast is where the marshes once lay.

In modern times, before the Medmerry Managed Realignment Scheme, this stretch of shore was the most threatened by coastal flooding in southeast England.

It was rated a one in one risk, meaning it was likely to flood every year.

During a severe flood, if Selsey’s one access road were inundated, people could be trapped there, with no electricity, sewage treatment, or emergency services.

Other nearby communities were also at risk: a settlement of small prefab, portable vacation homes to the west of Selsey called West Sands caravan park, and Bracklesham Bay, a village to the northwest.

These communities were protected by a “shingle embankment”—essentially, a low barrier made of rocks—erected where East Thorney once lay.

Every winter, workers would go out to the shore with bulldozers and push up the rocks afresh, a job that cost £300,000 (about US $413,000) annually.

In 2008, these efforts failed, and 30 people had to evacuate when the sea came in.

Damages cost £5-million (US $7-million).

Pippa Lewis, an environmental project manager with the UK Environment Agency, tells me, “Work during winter storms to maintain the embankment was dangerous, expensive—and wasn’t really working, to be honest.”

The goals of the Medmerry realignment were to make the local communities safer and to re-create lost coastal habitat that would benefit endangered species.

The Environment Agency bought land from farmers just behind the shingle bank so the marshes could reclaim space that was once theirs.

“From an historic perspective, a lot of what we are realigning is just land that we have claimed from the sea,” Hughes explains.

“There’s a sense of … we stole it from salt marsh 200 years ago; we should be putting it back.”

To see some of the almost 300 hectares of habitat, I decide to rent a bike.

At a small Selsey shop called Peddle Wise, I opt for a cruiser over a mountain bike because it has fenders.

A drenching rain the day and night before has left ponded water scattered across the flat terrain.

The Medmerry Managed Realignment Scheme allowed the sea to have its way with roughly 300 hectares of habitat.

Photo by Erica Gies

I set out past an old windmill, then cruise through West Sands caravan park, which seems mostly empty at this time of year.

At the edge of West Sands, I come to the southern end of the realignment project.

Here, workers removed the shingle bank barrier to the sea and built a new almost seven-kilometer-long, U-shaped levee that juts inland for close to two kilometers.

The new levee is made of local clay, already held strong with grass and other plants, and fortified on the sea edge by large rocks.

Standing atop the levee, I can look down into what was farmland in 2012 and is now a young marsh that floods with the tides.

The length of coastline that allows the sea to come in, more than 110 meters, is vast enough that the homes and buildings on the other side appear tiny on the horizon.

Now prone to sudden inundation, the intertidal area is not accessible to the public.

Instead, a winding inland path tracks the new slither of levee.

The hard-packed dirt of the path is pocked with puddles this morning, and some segments are fully flooded.

Reflecting the sky, their depth is impossible to gauge, so traversing them is a leap of faith.

I plow through at a steady pace, water shooting up in rooster tails from my tires, feet carefully balanced on pedals skimming just above the surface.

As I pedal, I pass through a variety of lowland habitats.

In the intertidal zone, the sandbars and rocks scattered across mudflats offer chunks of land for birds that make their living here, including dunlin, curlew, gray and ringed plovers, oystercatcher, redshank.

They hunt 13 species of marine mollusks that have moved in.

Just a short distance inland, saline plants are already established.

Still farther from the sea, reed beds give way to grassland and low shrubs.

David Rusbridge, the man whose family farmed in the area for 400 years, was asked by the UK Environment Agency to sell his 140 hectares so it could be returned to marsh.

His cousins, who owned 160 neighboring hectares, were also asked to sell.

“Me and my cousins, we sat down and talked about it,” he tells me.

“We were in no position to argue” with the government.

“They would have got their way one way or another. So our view was work with them, not work against them.”

He believes it was the right decision.

Rusbridge had been on the local flood defense committee, so he knows the challenges—and costs—of keeping out the sea.

When the national Environment Agency decides that it will no longer protect a stretch of coast, such as the annual bulldozing once required at Selsey, then it’s down to local districts to decide whether to pay to protect it.

The prospect of shouldering that financial burden locally changes the calculus, in his experience.

When the Medmerry Managed Realignment Scheme came along, Rusbridge decided he was ready to quit farming.

“If I’m entirely honest, conventional farming was quite difficult to make much money on it,” he says.

Consolidation of family farms like his by industrial companies created stiff competition.

And his children weren’t interested in farming.

The government paid him market price for his land, and given the tough economics of farming, “it seemed a reasonable way out.”

Still, after 400 years of family history here, “it marked the end of an era,” he adds a bit wistfully.

“But we were happy that it was going to go to a good environmental cause.” Both of his adult children work on environmental issues.

Since selling his land, Rusbridge has started a self-storage business in Bracklesham Bay.

“Self-storage pays a hell of a lot better than farming,” he laughs.

He still has friends who farm, and “when they’re struggling in the harvest, when it’s raining every day, I’m glad I’m not doing it.”

Part of Rusbridge’s former farm is now a section of the 183 hectares of intertidal area I gaze across from the path atop the levee.

Creating this habitat was a key goal of the project, and mitigation funds to compensate for similar habitat lost elsewhere to development helped pay for it.

Salt marshes are not just great buffers against wave energy, they are also vital nurseries for fish and serve as home and pantry for other wildlife.

Medmerry Nature Reserve encompasses freshwater areas, grasslands, saline lagoons, intertidal mudflats, and various other habitat types, which support a variety of birds, water voles, butterflies, dragonflies, and other animals.

Photo by Gillian Pullinger/Alamy Stock Photo

In addition to the intertidal areas (mudflat, salt marsh, and transitional grassland), Medmerry has freshwater and terrestrial habitats that are helping the United Kingdom to meet various national and international targets for biodiversity protection.

Already the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds has seen breeding populations of avocet and little ringed plovers.

Ducks such as teal and widgeon are prevalent.

Voles moved into new freshwater areas.

Creatures have even more room to find what they need thanks to physical connections between Medmerry and the older Pagham Harbour Local Nature Reserve—a tidal estuary on the east side of the Manhood Peninsula that was formed about 100 years ago when another barrier wall gave in to the sea.

Although other people around Selsey were less affected than the farmers who sold their land, public sentiment can be challenging on a project like this.

“People are understandably anxious about something that is going to alter their neighborhood,” Hughes, the ecologist, tells me.

The human instinct to build a fortress—such as the shingle barrier—is strong.

People tend to assume this will provide the best protection, so proposing its removal raises community concern and conflict, he warns.

Explaining the project to the community and engaging them in decisions can help.

“As they realized the benefits and protection they’d be afforded, people gradually became much more positive,” Hughes says.

The return of wildlife and more than 10 kilometers of new paths for walking, biking, or riding horses has brought economic benefit via a four-fold increase in visitors.

The intertidal habitat has also created fish-spawning and nursery areas that are helping to sustain local fishers.

Meanwhile, the salt marsh is doing its job protecting human habitat.

Flood risk to the area, once rated one in one year, has been revised to one in 100.

The main road to Selsey, a sewage treatment plant, and 348 homes benefit from that increased level of protection.

Now, several years later, the salt marsh continues to buffer the community, according to Lewis with the Environment Agency, despite “some big, big storms.”

While it’s hard to give up one’s land, the Medmerry project seems to have provided a happy ending for Rusbridge and his family.

But it’s not clear whether other landowners in the path of coastal realignment will do as well.

Medmerry was a flagship site, and the Environment Agency invested £28-million (US $38.5-million).

But the agency likely can’t afford the same for every coastal spot at risk.

While it will continue to look for opportunities to “manage realignment” in places that can create habitat for wildlife while reducing risks for people, some sites may be allowed to breach naturally, relinquishing control to nature without investing millions to micromanage it.

Rusbridge has moved into the hills, but he still goes down to the Manhood Peninsula often.

“I walk along the trail bank, the bund, and try to recognize which fields were which,” he says.

“It becomes harder as time goes on.” Day after month after year, water reclaims its space, obscuring human patterns.

In North Carolina, beach homes on the barrier islands are generally not multigenerational family affairs going back centuries, as in Medmerry.

Still, accepting retreat goes against the dominant culture’s belief that we can control water.

But proponents of managed retreat emphasize its inherent opportunity not just to save money in the long run, but to reduce trauma—such as watching one’s house float off into the sea.

Insecurity around the behavior and availability of water is destabilizing.

So admitting that water always wins is not weakness; rather, it’s the foundation for strength because it allows us to begin a conversation about what comes next.

By planning ahead, we can move toward something better—say, a more sustainable, equitable neighborhood—with less upheaval.

In letting go, in providing space for coastal ecosystems, we acknowledge the power of waterlands—to hold water, to hold carbon, to hold life, including us.

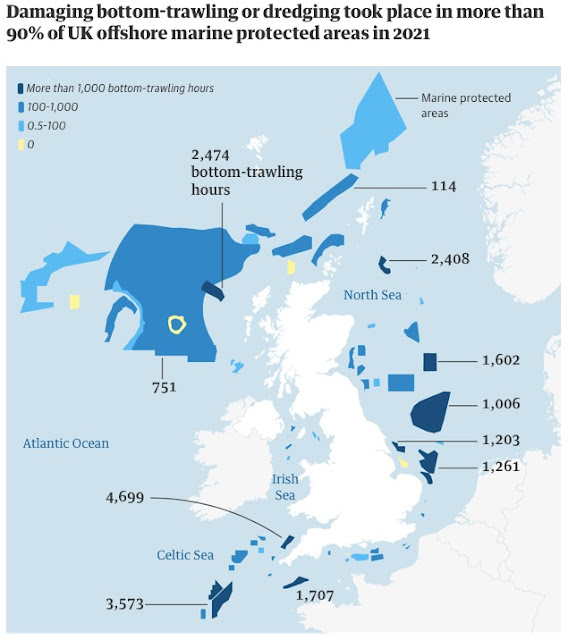

Starfish and anemones at Dogger Bank in the North Sea, where a ban on

bottom-trawling will shortly take effect. The harmful practice continues

at 58 other sites. Photograph: JNCC/PA

Starfish and anemones at Dogger Bank in the North Sea, where a ban on

bottom-trawling will shortly take effect. The harmful practice continues

at 58 other sites. Photograph: JNCC/PA

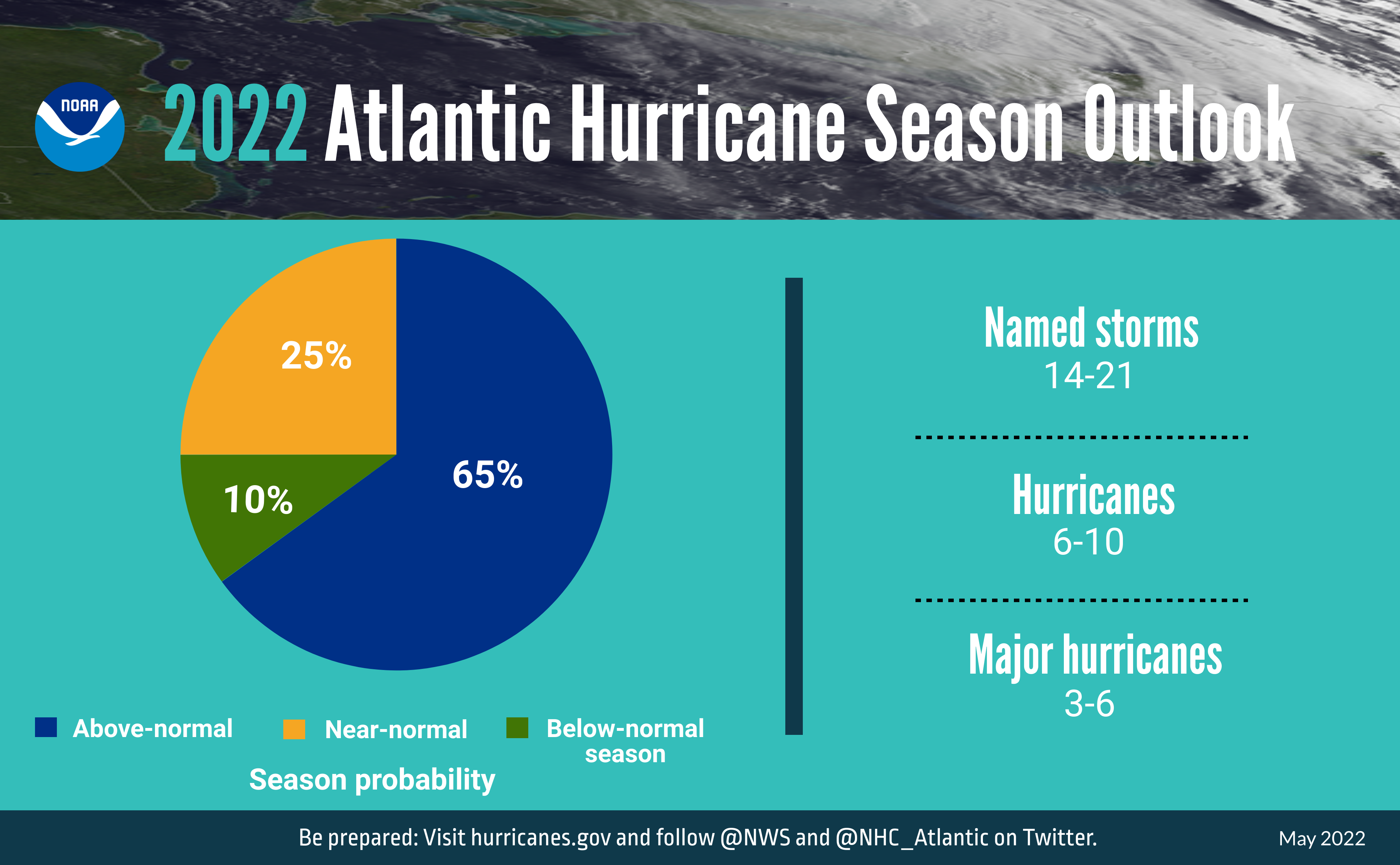

A summary infographic showing hurricane season probability and numbers of named storms predicted from NOAA's 2022 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook. (NOAA)

A summary infographic showing hurricane season probability and numbers of named storms predicted from NOAA's 2022 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook. (NOAA) A summary graphic showing an alphabetical list of the 2022 Atlantic tropical cyclone names as selected by the World Meteorological Organization. The official start of the Atlantic hurricane season is June 1 and runs through November 30. (NOAA)

A summary graphic showing an alphabetical list of the 2022 Atlantic tropical cyclone names as selected by the World Meteorological Organization. The official start of the Atlantic hurricane season is June 1 and runs through November 30. (NOAA)