see GeoGarage news

Saturday, April 17, 2021

Time flies in Google Earth’s biggest update in years

See humanity’s impact on the Earth through a global time-lapse video of the planet since 1984.

Explore the whole planet: https://goo.gle/timelapse

From Google by Rebecca Moore

For the past 15 years, billions of people have turned to Google Earth to explore our planet from endless vantage points.

You might have peeked at Mount Everest or flown through your hometown.

Since launching Google Earth, we've focused on creating a 3D replica of the world that reflects our planet in magnificent detail with features that both entertain and empower everyone to create positive change.

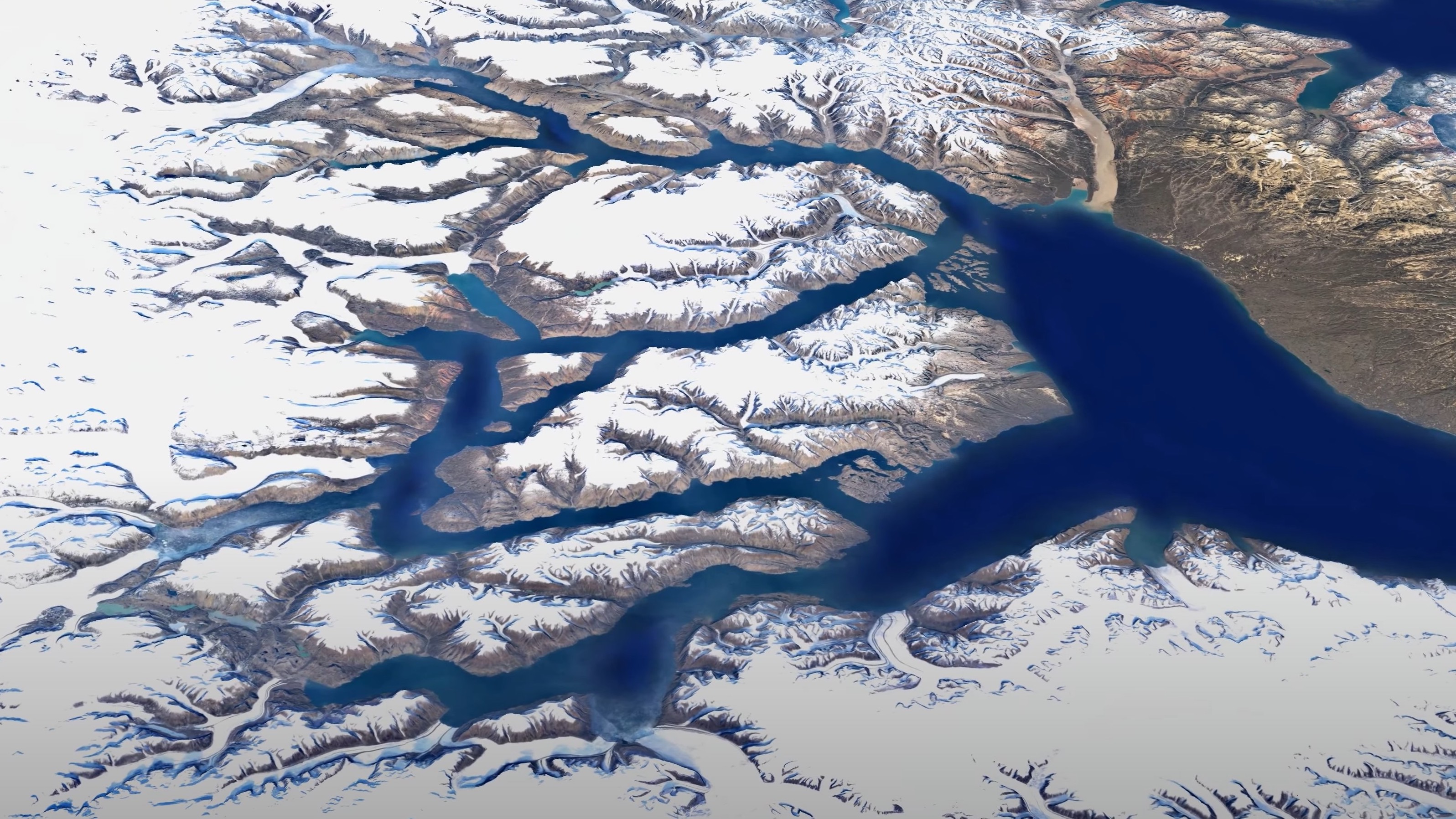

In the biggest update to Google Earth since 2017, you can now see our planet in an entirely new dimension — time.

With Timelapse in Google Earth, 24 million satellite photos from the past 37 years have been compiled into an interactive 4D experience.

Now anyone can watch time unfold and witness nearly four decades of planetary change.

Our planet has seen rapid environmental change in the past half-century — more than any other point in human history.

Our planet has seen rapid environmental change in the past half-century — more than any other point in human history.

Many of us have experienced these changes in our own communities; I myself was among the thousands of Californians evacuated from their homes during the state’s wildfires last year. For other people, the effects of climate change feel abstract and far away, like melting ice caps and receding glaciers.

With Timelapse in Google Earth, we have a clearer picture of our changing planet right at our fingertips — one that shows not just problems but also solutions, as well as mesmerizingly beautiful natural phenomena that unfold over decades.

To explore Timelapse in Google Earth, go to g.co/Timelapse — you can use the handy search bar to choose any place on the planet where you want to see time in motion.

Or open Google Earth and click on the ship’s wheel to find Timelapse in our storytelling platform, Voyager, to see interactive guided tours.

To explore Timelapse in Google Earth, go to g.co/Timelapse — you can use the handy search bar to choose any place on the planet where you want to see time in motion.

Or open Google Earth and click on the ship’s wheel to find Timelapse in our storytelling platform, Voyager, to see interactive guided tours.

Kuwait

We’ve also uploaded more than 800 Timelapse videos in both 2D and 3D for public use at g.co/TimelapseVideos.

You can select any video you want as a ready-to-use MP4 video or sit back and watch the videos on YouTube.

From governments and researchers to publishers, teachers and advocates, we’re excited to see how people will use Timelapse in Google Earth to shine a light on our planet.

Understand the causes of Earth’s change

We worked with experts at Carnegie Mellon University's CREATE Lab to create the technology behind Timelapse, and we worked with them again to make sense of what we were seeing.

As we looked at what was happening, five themes emerged: forest change, urban growth, warming temperatures, sources of energy, and our world’s fragile beauty.

Understand the causes of Earth’s change

We worked with experts at Carnegie Mellon University's CREATE Lab to create the technology behind Timelapse, and we worked with them again to make sense of what we were seeing.

As we looked at what was happening, five themes emerged: forest change, urban growth, warming temperatures, sources of energy, and our world’s fragile beauty.

Google Earth takes you on a guided tour of each topic to better understand them.

Timelapse in Google Earth shows the rapid change on our planet in context through five thematic stories.

For example, the retreat of the Columbia Glacier in Alaska is captured in the "Warming Planet" tour.

Putting time on Earth in the palm of our hand

Making a planet-sized timelapse video required a significant amount of what we call “pixel crunching” in Earth Engine, Google's cloud platform for geospatial analysis.

To add animated Timelapse imagery to Google Earth, we gathered more than 24 million satellite images from 1984 to 2020, representing quadrillions of pixels.

It took more than two million processing hours across thousands of machines in Google Cloud to compile 20 petabytes of satellite imagery into a single 4.4 terapixel-sized video mosaic — that’s the equivalent of 530,000 videos in 4K resolution!

And all this computing was done inside our carbon-neutral, 100% renewable energy-matched data centers, which are part of our commitments to help build a carbon-free future.

As far as we know, Timelapse in Google Earth is the largest video on the planet, of our planet. And creating it required out-of-this-world collaboration.

As far as we know, Timelapse in Google Earth is the largest video on the planet, of our planet. And creating it required out-of-this-world collaboration.

This work was possible because of the U.S. government and European Union’s commitments to open and accessible data.

Not to mention their herculean efforts to launch rockets, rovers, satellites and astronauts into space in the spirit of knowledge and exploration.

Timelapse in Google Earth simply wouldn’t have been possible without NASA and the United States Geological Survey’s Landsat program, the world’s first (and longest-running) civilian Earth observation program, and the European Union’s Copernicus program with its Sentinel satellites.

Cape Cod

What will you do with Timelapse?

We invite anyone to take Timelapse into their own hands and share it with others — whether you’re marveling at changing coastlines, following the growth of megacities, or tracking deforestation. Timelapse in Google Earth is about zooming out to assess the health and well-being of our only home, and is a tool that can educate and inspire action.

Visual evidence can cut to the core of the debate in a way that words cannot and communicate complex issues to everyone.

We invite anyone to take Timelapse into their own hands and share it with others — whether you’re marveling at changing coastlines, following the growth of megacities, or tracking deforestation. Timelapse in Google Earth is about zooming out to assess the health and well-being of our only home, and is a tool that can educate and inspire action.

Visual evidence can cut to the core of the debate in a way that words cannot and communicate complex issues to everyone.

Take, for example, the work of Liza Goldberg who plans to use Timelapse imagery to teach climate change.

Or the 2020 award-winning documentary “Nature Now” that uses satellite imagery to show humanity’s growing footprint on the planet.

See how cities around the globe have changed since 1984 through a global time-lapse video.

Timelapse for the next decade to come

In collaboration with our partners, we’ll update Google Earth annually with new Timelapse imagery throughout the next decade.

In collaboration with our partners, we’ll update Google Earth annually with new Timelapse imagery throughout the next decade.

We hope that this perspective of the planet will ground debates, encourage discovery and shift perspectives about some of our most pressing global issues.

Links :

Friday, April 16, 2021

Meet the families pioneering the future of remote work (and how they’re doing it in the world’s most amazing places

Remote work.

Antarctica style by satellite phone.

Circa 2001 Courtesy of Peter Lane Taylor

Antarctica style by satellite phone.

Circa 2001 Courtesy of Peter Lane Taylor

From Forbes by Peter Lane Taylor

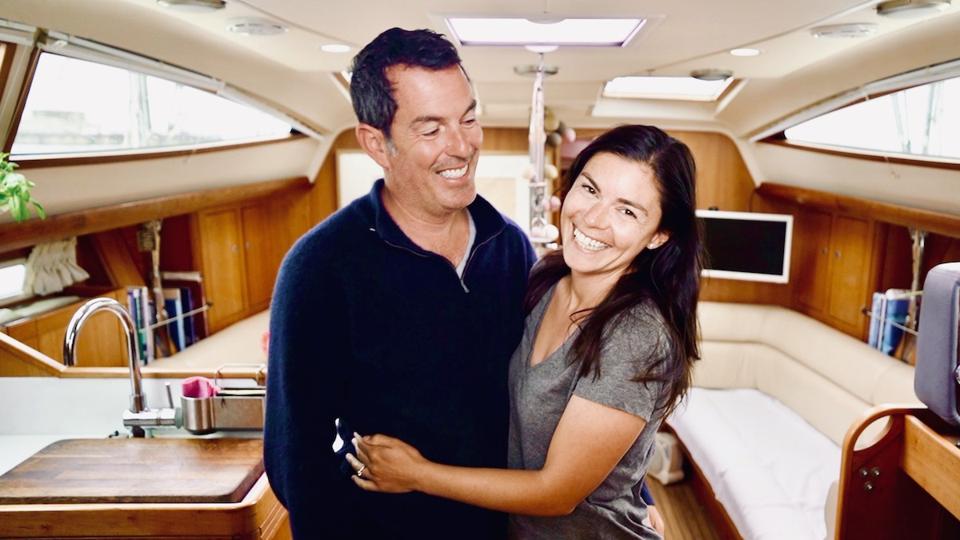

Nick Fabbri and Terysa Vanderloo—the former a 49 year-old dentist from the U.K. and the latter a 35 year-old Australian paramedic who’d met a decade earlier in India—can vividly remember the day that COVID-19 shut the world down.

Fabbri was onboard the couple’s 38’ sailing yacht Ruby Rose in a marina on France’s Atlantic coast, completing routine winter maintenance work.

Vanderloo was back in Adelaide, Australia, visiting with her mother and sister.

When reports hit their morning news feeds that borders around the world were about to lock down, Vanderloo flew immediately back to London, where Fabbri’s family lived.

The next day, Fabbri snagged one of the last trains back across the English Channel.

For the next three months the couple quarantined in London as the global economy shut down before France re-opened its borders to non-residents so that they could get back to Ruby Rose in late May.

“That was one of the strangest periods of our lives,” recalls Vanderloo.

“For years, everyone thought that we were crazy to give up our lives to move onto a sailboat and work remotely.

Then all of a sudden there was no place that everyone else wanted to be than isolating and working remotely on a boat.”

Two decades earlier, in late 2001, I experienced something similar to Fabbri and Vanderloo.

On the December day that U.S. and Coalition forces invaded Afghanistan in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, I was on an 8 knot broad reach over a place called “Point Nemo” (reputedly named after the famous submariner from Jules Verne's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea) on a 44’ steel ketch sailing from New Zealand to Argentina across the Southern Ocean ultimately en route to Antarctica.

There is no place that you can get farther from land on earth than here—precisely 1,670 miles from the Pitcairn Islands to the north, the Easter Islands to the northeast, and Maher Island (part of Antarctica) to the south.

Being in the middle of the ocean as it is, there’s nothing particularly remarkable about Point Nemo—no peak, no prayer flag, no welcome center—just a set of GPS coordinates on a screen (48°52.6′S, 123°23.6′W to be exact) to remind you that the nearest shipping lane is so far away that if your boat flounders your odds of survival are basically zero.

At first, it was hard to process the reality that the world was about to go to war from so far away.

Yet, ultimately it became impossible not to obsess over the news every minute of the day because there’s nothing else to do in the middle of nowhere.

Doing deals and running a start-up from here doesn't seem so crazy after all does it?

Getty

The irony of all of this two decades later is that the whole concept of living full-time on a sailboat, working remotely from some absurdly yet remotely beautiful place on earth, and staying connected to the world in a wetsuit from the waist down all of a sudden now seems so predictably, “Of course you can”, instead of “You do what?! From where?!”.

Thanks to a global pandemic that no one foresaw—from tech titans in Aspen gondola-Zooming with investors to PR consultants who’ve decided that there’s no better time to sail around the world—work’s new remote normal is here.

And it’s spectacular.

“I usually wake up with the sun shining through our hatch around 7:30 am,” 40-year old Erin Carey tells me of her typical workday, emailing from her 1984 Moody 47’ sailing yacht Roam, currently wintered up in a marina in the Azores Islands 800 miles west of Spain in the North Atlantic Ocean.

Carey, her husband David, 38, and three children have been sailing around the world for four years now.

Roam, in addition to the family’s now permanent home, also doubles as Carey’s remote office for her global PR firm, Roam Generation, which she’s been running digitally pre-pandemic since 2018.

When I finally catch up with her, it’s not so much a sense of vindication that I get from her on COVID’s unleashing a new wave of remote, mobile workers.

It’s more the satisfaction of inevitability.

“We get ready for the day just like we used to on land,” says Carey.

“After breakfast, I apply makeup if I have a Zoom meeting and put on neat clothes, not sweats, so I feel like I’m at work.

I’m usually in the ‘office’ from 8:30 am to 3 pm in the aft cabin which gives me privacy while Dave is homeschooling the kids and working on the boat.

Pre-pandemic this schedule all seemed so strange to everyone.

Now all of a sudden it’s everyone’s new normal.”

Work’s new remote permissibility since the pandemic began already has re-shaped everything, including crushing the commercial office space sectors in cities like New York and San Francisco and making billions of dollars of new public transit already obsolete.

Yet, when it comes to the hidden white-collar, underworld that’s always dreamed of ditching the office and working remotely, the pandemic has forced an existential labor market question thousands of employers never wanted to address because that would risk validating the very premise of it for millions of potential workers: What if I moved 3,000 miles away and did the same amazing job I do now? Would you have a problem with that?

All of which raises a more practical, still-to-be-proven question: when it comes to “offshore” talent, is there now any such thing as an office too far?

In practice, the simple answer lies almost entirely with technology rather than some kind of woke work culture revolution.

I moved aboard my first sailboat and started working remotely in Key West, Florida in 1994.

Back then, the mobile “stack” available to people like me wasn’t particularly empowering.

The 8” Motorola flip phone I connected to my NEC laptop running Earthlink webmail took 28 minutes to successfully upload my first test email from my cockpit, all while angling the phone towards the cell tower as the boat shifted at anchor.

By 2001, when I sailed over Point Nemo to Antarctica, we’d upgraded to a satellite phone that patched into a 12-pound Toshiba laptop which could send and receive three to four sentence messages at $3.00/minute from anywhere in the world.

Photos and videos? Forget about it.

Phone calls? $6.00/minute.

My wife and I still joke that it was the $7,000 satellite phone bill that kept us together to this day.

But we made it work, hacks and all.

And, more importantly at the time, the whole concept intrigued everyone from editors and readers to film producers to corporate sponsors.

Who works from the middle of nowhere?

Well, back then, a lot of people you never knew about.

But now, post COVID-19, just about everyone else whose employer will give them the greenlight to do so because the technological barriers to entry are more democratized than ever.

Home office redefined and fully connected on the sailing yacht Roam

Courtesy of Erin Carey/Roam

For today’s untethered entrepreneurs like Carey, today’s mobile stack gets smaller, faster, more durable, and more reliable every year.

Carey’s core kit in Roam’s aft cabin includes a 16-inch Macbook Pro with a wireless mouse and keyboard, a 24” pivoting wall mounted monitor for dual screen viewing, iPhone 12 Pro, Ipad Pro, Airpod Pros, and an Apple watch.

Once Carey and her husband arrive in a new country, they buy 2-3 SIM cards for their phones with as much data as possible and then use them as hotspots for 24/7 internet access.

“We put one of those SIM cards into a Digital Yacht 4G Pro Connect 3G/4G Router installed on our boat which utilizes the latest MIMO technology with dual external antennas for fast, long range access that also incorporates a full function Wifi router so multiple devices can connect wirelessly at once,” says Carey.

“We’re also wired with LAN and WAN ports for connection to high power WiFi devices or satellite modems.”

As far as the remote office is concerned, Carey’s work life coalesces around a cloud of Google Docs, Google Sheets, FreshBooks, Apple Mail, Mailbutler (to track emails), Zoom, iCal, WhatsApp and Messenger, FreshBooks for accounting, Canva, Later, and Dropbox to run a collaborative ship that her entire team can access globally anytime, anywhere.

Her growing staff is also increasingly deconstructed and virtual.

“I have an assistant in Australia, a freelance writer in America, a social media assistant who also lives on a boat, and a team of freelance PR professionals who I’ve never met in person,” says Carey.

“Yet, I’m still able to run my business and no one would know the difference unless I told them.

When I’m sailing across an ocean, which is actually very infrequently, we also have a satellite phone to receive text messages and an SSB (single sideband) radio on our boat that can download emails and my team holds down the reins until I get to where I'm going.”

Fabbri and Vanderloo hard are work aboard Ruby Rose

Terysa Vanderloo holding down the office helming Ruby Rose

Courtesy of Ryby Rose

Carey and her husband David’s cord-cutting decision to work remotely and pre-wire their life to function anywhere before COVID hit—while seemingly prescient now—isn’t actually anything new.

It was around the same time prior to COVID’s outbreak that Fabbri and Vanderloo also quit their jobs to sail around the world.

Along the way they decided to film their adventure for family and friends.

That, in turn, grew into a successful YouTube channel as they sailed Ruby Rose across oceans to exotic locations.

It’s now one of the most popular sailing channels on the platform.

“In 2017 we were running out of money and also wanting a creative outlet so we decided to start our own YouTube channel,” recalls Vanderloo.

“And what started as a hobby turned into a full-time business.

We're now able to financially support ourselves entirely with our YouTube earnings.”

As a result, Fabbri and Vanderloo have a little more hardware and software running under the hood to stay literally and metaphorically afloat.

“We now film and produce sailing and boat life videos for a living,” explains Vanderloo, “So the amount of gear—including cameras, audio equipment, drones, and accessories—that we require for that is significant.

When something breaks, we can't just get it replaced with next day delivery like most people.

So we have two of every item that we rely on most while trying to stick to the necessities and not have any superfluous equipment.

That minimalist mentality is part of living on a boat and working remotely anyways.

But it still stacks up when you're doing what we’re doing content wise.”

After 5 years of living onboard, sailing 25,000 nautical miles, crossing 2 oceans and living on three continents, this is the end.

This week we finally sail Ruby Rose across the English Channel and home to the UK in order to sell her to her new owners.

This is our penultimate sail and our last big crossing- and there's a bit of everything!

Join us for our final 100nm passage through the Aldernay Race, across the shipping lanes of the English Channel and to the Solent.

Our life as a sailing couple is almost at the end of this chapter.

The editing suite aboard Ruby Rose

Courtesy of Ryby Rose

Not surprisingly, Fabbri and Vanderloo’s biggest technological bottlenecks—like the Careys’—are no different than every other remote worker’s: power generation, battery life, and access to smoking hot high-speed internet access.

“Part of living on a boat is having a limited power supply,” Vanderloo tells me of the couple’s constant electricity battles, “The amount of charging leads and battery packs that we have for our cameras is crazy.

Then there’s all of the gear we need to do the editing and publishing—our laptops, external SSDs, voice over microphones and headphones.

In order to do our digital marketing and stay active on our socials, we also rely heavily on our tablets, phones and smart watches.

We use solar power to generate electricity and frequently we simply don't have the power to work.

Sometimes we also actually have to make water, run the lights, and operate the boat.”

Staying connected afloat can sometimes be even harder than having the power to do so.

“Connectivity is still our biggest challenge working off the grid,” adds Vanderloo.

“This is improving with every year as internet becomes cheaper and faster.

But we still rely on local SIM cards and tethering off our phones for 4G internet, and the signal can often be weak or patchy.

We also have to wait until we're somewhere with fast WiFi before backing up our raw footage to the cloud or doing major software updates, which means we need to create extra backups on external hard drives.

When we're in countries with poor internet infrastructure, finding internet that's fast enough to upload a video and schedule our social media posts is also a major issue.

Living remotely, especially on a boat, is full of challenges and most of them revolve around the most basic issues of connectivity.”

Working remotely particularly on a boat isn't all sunsets and rum drinks.

"Everything always breaks," says Carey

Courtesy of Erin Carey / Roam

"Everything always breaks," says Carey

Courtesy of Erin Carey / Roam

For Carey and her husband, staying connected while living and working untethered was also their first, biggest hack to sort out.

Living on a boat or in a van or constantly moving around means that you don’t have a fixed address, which means that you often can’t receive Amazon deliveries or shop online.

It also means that if we lose our bank card or our driver’s license expires, it can be a disaster.

But over time we’ve figured it out—especially the business side.

My clients have always been located all over the world, so we’ve always communicated via email and Zoom, signed contracts via Docusign and sent funds via Wise (was TransferWise), Stripe, or Paypal.

At this point, there’s not much we can’t do even in the middle of nowhere.”

The other biggest challenge of working remotely—particularly on a boat—are physics and entropy, says Carey.

Simply put, shit breaks.

“There’s a saying that ‘BOAT’ stands for ‘Bring Out Another Thousand’.

And I’d say that's pretty accurate.

The endless breakages and the insurmountable amount of work that is involved with living on a boat and travelling full time can be extremely challenging.”

When the things that break are also your laptops and wireless routers that keep your remote businesses tethered to the outside world, that can be doubly catastrophic, adds Vanderloo, whose YouTube channel is based on delivering subscribers (and sponsors) regular content when they expect it (i.e., the customers).

“We've had more things than we can remember lost overboard.

I once left a hatch open and it rained, soaking my laptop and rendering it useless.

I couldn't just pop into Apple and get it fixed so I had to wait, unable to do any work, for weeks before finding a computer repair store.

We also recently lost our best microphone overboard as we were sailing, so we had to do a ‘man overboard’ drill to get the microphone back.

But it was good practice!”

I'm the guy on the far right.

Yes we all crammed into that tent.

Antarctica Peninsula circa 2001

Courtesy of Peter Lane Taylor

When I returned from sailing to Antarctica after 8 months living aboard, the biggest challenge I realized I had endured was learning to live with six other people in under 44’—which, during the pandemic, has similarly tested virtually every family and couple in America to the breaking point over the past year that’s been confined at home, most of them for the first time ever.

For those toying with uprooting, working remotely, and embracing romantic #yachtlife and #vanlife tags more permanently, these aren’t minor, aberrant concerns.

“Separation and privacy is still our biggest challenge,” Fabbri and Vanderloo tell me.

“And everyone during the pandemic lock downs has learned the same thing.

On a boat you barely have enough personal space, let alone workspace.

We’ve had burnout from this in the past because we haven’t been unable to create the right boundaries, and so we now have very firm rules: we only do computer work during office hours, and we finish by 5 p.m.

every day so we can enjoy our evenings together.

We don't have a dedicated office or work area, and so we set up our laptops and editing gear every day, then pack everything away in the evening.”

For Carey, who’s running an international PR agency around the clock while simultaneously raising three children and living aboard, the key also is creating artificial boundaries that work around her lifestyle and job both in time as well as space.

“Running a PR business with clients all over the world means that I go to sleep when the other half of the world is waking up,” says Carey.

“Which means that my workday can be really long if I’m not careful to switch off.

At the same time, the lure of a new city or a beach is always right outside my door, and sometimes it takes all my strength not to shut the computer and head off on an adventure.

Like everything, it’s a juggling act but we've implemented strategies to try to combat it such as not replying to emails after dinner or before breakfast and heading out into nature in some way every day.

And if we decide to swap things up for a few days, we can.

But the basic boundaries don’t change.”

Carey's kids going local

Courtesy of Erin Carey / Roam

For families that have decided to untether fully and work remotely both before and during the pandemic, the ultimate beneficiary of that ability to blur the lines while maintaining boundaries are kids, says Carey.

“Working remotely we have the advantage that we’re not trying to replicate a typical school day or workday,” Carey tells me.

“So flexibility is the key for us.

Our children are doing an online school that’s self-paced so if we decide to do school in the afternoon instead of the morning, or skip a day mid-week to explore a museum or climb a mountain, then we can do that without consequence.

This also gives us some pretty great bargaining chips to encourage the kids to get their school done: ‘Want to go snorkeling this afternoon kids? Then get your schoolwork done!’”.

That flexibility, says Carey, leads to happier, better adjusted children.

“Living remotely on a boat has changed my kids.

They are quietly confident with an ability to converse with adults or children alike, yet they are friendly, welcoming and inclusive.

They don’t see anyone by age, sex, or color, instead they just see a playmate.

They’ve visited 15 countries, watched turtles laying eggs on the beach under a stary sky, climbed to the top of a volcano, seen animals they previously didn’t know existed, and ordered food in French, Spanish and Portuguese.

They’ve learned to entertain themselves with the simple pleasure of a book or rocks and sticks on a deserted beach, and also become experts in the weather, oceanography, the moon cycles and the geography of the world since we are always looking at maps and charts.

Happy kids, happy boat.

Happy boat, happy life.”

Happy boat, happy life.

Happy life, happy marriage.

Nick Fabbri and Terysa Venderloo

Happy life, happy marriage.

Nick Fabbri and Terysa Venderloo

Courtesy of Ryby Rose

So how much does it cost to sail around the world? Costs are important, and this week we talk about money and what experience has shown us.

As for the original question—is there now a remote office too far?—it doesn’t look like it.

What’s equally certain is that remote work, mobile lifestyles like the Careys’ and Fabbri and Vanderloo’s that were once fringe aren’t exiting the mainstream any time soon.

“When we started our YouTube channel, I didn't see it as a way of earning money,” says Vanderloo of the couple’s digital launch back in 2017.

“But as our channel grew and scope for income grew with it, we poured more and more time and energy into it and now have complete autonomy.

The pandemic has accelerated this shift towards remote work that was already underway, but perhaps not widely accepted by many companies due to the perception that you weren't as committed or productive if you were working from your home.

After a year of enforced remote working, many company owners are seeing the benefits and I don't think there's any turning back the clock on this one.

That's great news for people in their 20s, 30s, 40s too young to retire, but still wanting to live an alternative lifestyle.

They can carry on working from their boat or van or wherever, still earn income, and lead an amazing life.”

For Carey, who as a PR professional has the challenge of representing other digital nomads, travel influencers, and other mobile brands, the most essential transformation when it comes to remote work is how COVID-19 has forced a more global, cultural conversation.

“Digital nomads were often perceived as social media influencers sitting on the beach with a laptop drinking a cocktail out of a coconut,” Carey says.

“And I still think that we have a little way to go before that term ‘nomad’ isn’t fraught with skepticism.

But the pandemic has created a tipping point moment in my opinion and generated a dialog around digital nomadism where more and more people are questioning why they too can’t do their job from anywhere in the world.

In 20 years, my kids won’t sit in an office all day—not only because they are being raised on a boat, but because most jobs will be done remotely.

So as far as I’m concerned we’re just getting them better prepared.”

What’s equally certain is that remote work, mobile lifestyles like the Careys’ and Fabbri and Vanderloo’s that were once fringe aren’t exiting the mainstream any time soon.

“When we started our YouTube channel, I didn't see it as a way of earning money,” says Vanderloo of the couple’s digital launch back in 2017.

“But as our channel grew and scope for income grew with it, we poured more and more time and energy into it and now have complete autonomy.

The pandemic has accelerated this shift towards remote work that was already underway, but perhaps not widely accepted by many companies due to the perception that you weren't as committed or productive if you were working from your home.

After a year of enforced remote working, many company owners are seeing the benefits and I don't think there's any turning back the clock on this one.

That's great news for people in their 20s, 30s, 40s too young to retire, but still wanting to live an alternative lifestyle.

They can carry on working from their boat or van or wherever, still earn income, and lead an amazing life.”

For Carey, who as a PR professional has the challenge of representing other digital nomads, travel influencers, and other mobile brands, the most essential transformation when it comes to remote work is how COVID-19 has forced a more global, cultural conversation.

“Digital nomads were often perceived as social media influencers sitting on the beach with a laptop drinking a cocktail out of a coconut,” Carey says.

“And I still think that we have a little way to go before that term ‘nomad’ isn’t fraught with skepticism.

But the pandemic has created a tipping point moment in my opinion and generated a dialog around digital nomadism where more and more people are questioning why they too can’t do their job from anywhere in the world.

In 20 years, my kids won’t sit in an office all day—not only because they are being raised on a boat, but because most jobs will be done remotely.

So as far as I’m concerned we’re just getting them better prepared.”

I think I'll just keep working from here for now, thanks

Courtesy of Erin Carey / Roam

As for when any of these new normal, remote work pioneers might be headed back to shore and re-embracing the lives they once knew?

“We have no plans to return to living on land,” Ruby Rose’s Fabbri and Vanderloo tell me.

“There are so many sailing adventures to be had.

It’s hard to imagine missing out on them at this point if we can make a digital living capturing those stories for others.”

Carey and her husband David don’t appear to be in any rush to ditch #yachtlife any time soon either.

“Our motto is ‘as long as it’s fun’,” says Carey.

“We’ve sold our house, our cars and all of our possessions to live this life.

This boat is our home.

Whether that ends up being 2 years, 5 years or 10 years, who knows? What I do know is that this lifestyle has given us a threshold for freedom, adventure, and autonomy that is much higher than what can be achieved living a normal life.

All of these experiences have made me stronger.

I am far more patient than I used to be and far more capable than I ever thought possible and it’s this sense of badassery that helps us grow as people.

As they say, nothing good happens in comfort zones.

So will we ever be happy living in the rat race again?”

Given the new remote work normal the pandemic has ushered in, I’ll take the odds on, “Probably not”.

Thursday, April 15, 2021

Seabirds spend nearly 40% of time beyond national borders, study finds

The Waved Albatross' impressive wingspan helps is roam thousands of miles

© Mike's Birds

From BirdLife by Jessica Law

Scientists have found that albatrosses and large petrels spend 39% of their time on the high seas – areas of ocean where no single country has jurisdiction.

How can we make sure these vital habitats don’t fall through the cracks?

When we think of the high seas, images of swashbuckling pirates setting course to distant horizons often spring to mind. During the Golden Age of piracy, these lawless buccaneers were considered ‘hostis humani generis’ – enemies of all humankind – meaning that any country had the right to seize a pirate ship in international waters.

Today, there’s increasing evidence that we may need to take a similar approach when conserving marine life, but in a more positive sense – seeing it as a universal responsibility that nations must work together to safeguard.

One such piece of evidence came to light today, when a new study revealed that albatrosses, and their close cousins the large petrels, spend 39% of their time in oceans beyond national jurisdiction.

One such piece of evidence came to light today, when a new study revealed that albatrosses, and their close cousins the large petrels, spend 39% of their time in oceans beyond national jurisdiction.

Using tracking data from 5,775 birds across 39 species, researchers found that all species regularly cross into the waters of other countries, meaning that no single nation can adequately ensure their conservation.

Furthermore, all species depended on the high seas: international waters that cover half of the world’s oceans and a third of the earth’s surface.

This is particularly worrying because albatrosses and large petrels are among the world’s most-threatened animals, with over half of the species at risk of extinction.

This is particularly worrying because albatrosses and large petrels are among the world’s most-threatened animals, with over half of the species at risk of extinction.

At sea they face numerous dangers including injury and mortality from fishing gear, pollution and loss of their natural prey due to overfishing and climate change.

According to co-author Maria Dias, from BirdLife International: “Negative interactions with fisheries are particularly serious in international waters because there is less monitoring of industry practices and compliance with regulations. Also, beyond fish there is currently no global legal framework for addressing the conservation of biodiversity in the high seas.”

For example, the Amsterdam Albatross Diomedea amsterdamensis (Endangered) spends 47% of its time in international waters in the Indian Ocean.

According to co-author Maria Dias, from BirdLife International: “Negative interactions with fisheries are particularly serious in international waters because there is less monitoring of industry practices and compliance with regulations. Also, beyond fish there is currently no global legal framework for addressing the conservation of biodiversity in the high seas.”

For example, the Amsterdam Albatross Diomedea amsterdamensis (Endangered) spends 47% of its time in international waters in the Indian Ocean.

Although it benefits from strong protection at its breeding colony on Amsterdam Island (one of the French Southern Territories), its conservation at sea is much more challenging.

When roaming the seas in search of squid prey, the <100 remaining adults use a vast area stretching from South Africa to Australia – requiring international coordination to minimize the risk of death in fishing gear.

The Amsterdam Albatross is currently only protected at its breeding grounds

© Vincent Legendre

Hope is on the horizon.

The international scale of this study is itself a perfect example how seabirds can connect nations. Uniting researchers from 16 countries, who agreed to share their data through BirdLife’s Seabird Tracking Database, this global collaboration couldn’t have come at a more important time: the United Nations are currently discussing a global treaty for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity in international waters.

“Our study unequivocally shows that albatrosses and large petrels need reliable protection that extends beyond the borders of any single country,” says Martin Beal, lead author of the study at the Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre at ISPA - Instituto Universitário in Lisbon, Portugal.

“Our study unequivocally shows that albatrosses and large petrels need reliable protection that extends beyond the borders of any single country,” says Martin Beal, lead author of the study at the Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre at ISPA - Instituto Universitário in Lisbon, Portugal.

“This treaty represents a massive opportunity for countries to commit to protecting species wherever they may roam.”

Legal measures up for discussion under the treaty, such as introducing environmental impact assessments for industrial activities in the high seas, have the potential to significantly reduce pressure on species that call these oceans home.

Carolina Hazin, Marine Policy Coordinator for BirdLife, sees the study as part of an even bigger picture.

Legal measures up for discussion under the treaty, such as introducing environmental impact assessments for industrial activities in the high seas, have the potential to significantly reduce pressure on species that call these oceans home.

Carolina Hazin, Marine Policy Coordinator for BirdLife, sees the study as part of an even bigger picture.

“No conservation of migratory species can be effective if fragmented in terms of space, time and activity. This study reinforces the urgency that the United Nations adopt the high seas treaty, which in turn will contribute to the Convention on Biological Diversity’s ambitious global framework to protect all nature over the next decades.”

The old saying “out of sight, out of mind” didn’t work for the pirates of the Golden Age.

The old saying “out of sight, out of mind” didn’t work for the pirates of the Golden Age.

And as the swashbuckling explorers of the animal world, it shouldn’t apply to seabirds either.

Links :

Wednesday, April 14, 2021

Everything you need to know about the plan to release treated Fukushima water

The storage tanks for treated water at the tsunami-crippled Fukushima

nuclear power plant.

They will be full by the second half of 2022.

Photograph: Kyodo/Reuters

From The Guardian by AFP

Japan has announced it will dump 1m tonnes of contaminated water into the ocean, sparking controversy

Japan’s decision to release more than 1m tonnes of treated radioactive water from the stricken Fukushima nuclear plant into the sea has sparked controversy inside and outside the country.

Here are some questions and answers about the plan, which is expected to take decades to complete.

What is the processed water?

Since the 2011 nuclear disaster, radioactive water has accumulated at the plant, including liquid used for cooling, and rain and groundwater that has seeped in.

An extensive pumping and filtration system known as Alps (advanced liquid processing system) extracts tonnes of newly contaminated water each day and filters out most radioactive elements.

Since the 2011 nuclear disaster, radioactive water has accumulated at the plant, including liquid used for cooling, and rain and groundwater that has seeped in.

An extensive pumping and filtration system known as Alps (advanced liquid processing system) extracts tonnes of newly contaminated water each day and filters out most radioactive elements.

The plant operator, Tepco, has built more than 1,000 tanks to hold some 1.25m tonnes of processed water at the site but they will be full by the second half of 2022.

The Alps process removes most of the radioactive isotopes to levels below international safety guidelines for nuclear plant waste water.

But it cannot remove some, including tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen that experts say is only harmful to humans in very large doses.

The half-life of tritium – the time needed for one half the atoms of a radioactive isotope to decay – is 12.3 years.

In humans, it has an estimated biological half-life of seven to 10 days.

How will it be released?

Japan’s government has backed a plan to dilute the processed water and release it into the sea.

The government says the process meets international standards, and it has been endorsed by the International Atomic Energy Agency.

“Releasing into the ocean is done elsewhere,” IAEA’s director general, Rafael Mariano Grossi, has said. “It’s not something new. There is no scandal here.”

The release is not likely to begin for at least two years and will take decades.

A government spokesman, Katsunobo Kato, said the dilution would reduce tritium levels to well below standards set domestically and by the World Health Organization for drinking water, with IAEA supervision.

Why is it controversial?

Environmental groups like Greenpeace, which opposes nuclear power, say radioactive materials like carbon-14 that remain in the water can “be easily concentrated in the food chain”.

They allege that accumulated doses over time could damage DNA, and want to see the water stored until technology is developed to improve filtration.

Local fishing communities worry that years of work to convince consumers that Fukushima’s seafood is safe will be wiped out by the release.

“The message from the government that the water is safe is not reaching the public, that’s the huge problem,” an official with the association of Fukushima fishermen unions told Agence France-Presse.

He said trading partners had warned they would stop selling their products and consumers had said they would stop eating Fukushima seafood if the water were released: “Our efforts in the past decade to restore the fish industry will be for nothing.”

Environmental groups like Greenpeace, which opposes nuclear power, say radioactive materials like carbon-14 that remain in the water can “be easily concentrated in the food chain”.

They allege that accumulated doses over time could damage DNA, and want to see the water stored until technology is developed to improve filtration.

Local fishing communities worry that years of work to convince consumers that Fukushima’s seafood is safe will be wiped out by the release.

“The message from the government that the water is safe is not reaching the public, that’s the huge problem,” an official with the association of Fukushima fishermen unions told Agence France-Presse.

He said trading partners had warned they would stop selling their products and consumers had said they would stop eating Fukushima seafood if the water were released: “Our efforts in the past decade to restore the fish industry will be for nothing.”

What about Fukushima seafood?

The government says radioactive elements in the water are far below international standards, pointing out that waste water is regularly discharged from nuclear plants elsewhere.

Even releasing all the stored water in a single year would produce “no more than one-thousandth the exposure impact of natural radiation in Japan,” the foreign ministry said in a reply to a UN report.

For food, Japan nationally sets a standard of no more than 100 becquerels of radioactivity per kilogram (Bq/kg), compared with 1,250 Bq/kg in the EU and 1,200 in the US.

But for Fukushima produce, the level is set even lower, at just 50 Bq/kg, in an attempt to win consumer trust. Hundreds of thousands of food items have been tested in the region since 2011.

What do scientists say?

Michiaki Kai, an expert on radiation risk assessment at Japan’s Oita University of Nursing and Health Sciences, said it was important to control the dilution and volume of released water.

But “there is consensus among scientists that the impact on health is minuscule”, he told AFP.

Still, “it can’t be said the risk is zero, which is what causes controversy”.

Geraldine Thomas, chair of molecular pathology at Imperial College London and an expert on radiation, said tritium “does not pose a health risk at all – and particularly so when you factor in the dilution factor of the Pacific Ocean”.

She said carbon-14 was also not a health risk, arguing that chemical contaminants in seawater like mercury should concern consumers more “than anything that comes from the Fukushima site”.

On eating Fukushima seafood, “I would have no hesitation whatsoever,” she added.

Links :

- The Guardian : Fukushima: Japan announces it will dump contaminated water into sea

- NYTimes : Fukushima Wastewater Will Be Released Into the Ocean, Japan Says

- DailyMail : Japan says it will begin releasing treated radioactive water from Fukushima into the Pacific Ocean in two years – sparking anger in China and South Korea

- NYTimes : Japan’s Plan for Fukushima Wastewater Meets a Wall of Mistrust in Asia

- Reuters : Countries react to Japan's plans to release Fukushima water into ocean

- GeoGarage blog : Fukushima fishermen concerned for future ...

Tuesday, April 13, 2021

China turning South China Sea supply ships into mobile surveillance bases

The Sansha 1 supply ship participating in a joint rescue exercise with Chinese maritime law enforcement vessels in June 2017 in the Paracel Islands.

From RFA by Zachary Haver

China is upgrading two of its civilian South China Sea supply ships with new high-tech surveillance equipment to help the vessels track ships from the United States, Vietnam, and other foreign countries, new Chinese government procurement documents show.

This is just the latest instance of the Chinese government leveraging civilian assets to pursue its national security interests in the South China Sea, a common practice under China's strategy of "military-civil fusion."

The contract for this project was awarded Thursday to Zhejiang Dali Science and Technology Co., Ltd. by Sansha City, which is responsible for administering China’s maritime and territorial claims in the contested South China Sea.

Dali, which appears to also work with the Chinese military, is set to provide a pair of its “DLS-16T Long-Distance Optoelectronic Monitoring Systems” for use on the city’s two main supply ships — the Sansha 1 and Sansha 2 — for 3,830,000 yuan ($547,000).

Multi-function supply ships

The Sansha 1 and Sansha 2 are mainly tasked with supplying Woody Island, which is China’s largest base in the Paracels and serves as the headquarters for Sansha City.

Though the Paracels are claimed by Vietnam, China, and Taiwan, only the PRC occupies any features in the archipelago.

But both vessels have also ventured down further south to the Spratlys, where China is locked in maritime and territorial disputes with Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Brunei.

But both vessels have also ventured down further south to the Spratlys, where China is locked in maritime and territorial disputes with Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Brunei.

Automatic identification system (AIS) data from April 2020 to April 2021 showing the Sansha 1 and Sansha 2 operating in the Paracels and Spratlys.

Data: MarineTraffic; Analysis: RFA.

The Sansha 1 came into service in January 2015 and the Sansha 2 completed its maiden voyage in August 2019.

This allowed the city’s older Qiongsha 3 supply ship to focus on supplying China’s settlements in the Crescent Group in the Paracels, state-run Hainan Daily reported.

State-owned CSSC Guangzhou Shipyard International, which built the Sansha 2, said that the 128-meter-long vessel would integrate “transportation and supply, administrative jurisdiction, emergency rescue command, emergency medical assistance, and island and reef scientific survey capabilities.”

The company also stated that the Sansha 2 would “play an important role in defending the motherland’s southern gate” — which is how China sometimes refers to its claimed territory in the disputed South China Sea.

State-owned CSSC Guangzhou Shipyard International, which built the Sansha 2, said that the 128-meter-long vessel would integrate “transportation and supply, administrative jurisdiction, emergency rescue command, emergency medical assistance, and island and reef scientific survey capabilities.”

The company also stated that the Sansha 2 would “play an important role in defending the motherland’s southern gate” — which is how China sometimes refers to its claimed territory in the disputed South China Sea.

Satellite image from December 2020 showing the Sansha 1 and Sansha 2 docked at Woody Island. Image: Planet Labs Inc; Analysis: RFA.

Defending the motherland’s southern gate

Once they are outfitted with their new surveillance equipment, the Sansha 1 and Sansha 2 will be able to play an even greater role in asserting China’s claims.

According to bidding documents reviewed by RFA, the DLS-16T Long-Distance Optoelectronic Monitoring Systems from Dali are intended to allow the supply ships to “carry out omnidirectional search, observation, surveillance, and video evidence collection against maritime and aerial targets” such as ships, overboard people, objects floating in the sea, and aircraft under all weather conditions, 24 hours a day.

Sansha City was seeking a tracking system that would integrate visible light imaging, infrared thermal imaging, automatic target tracking, radar, fog penetration, image enhancement, the U.S.-run satellite navigation system GPS, the Chinese equivalent system BeiDou, and other capabilities, the bidding documents show.

The software system for the tracking equipment is to be used to detect, identify, and track “sensitive ships” from countries like the United States, Japan, the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Taiwan, as well as record and display this information in real-time, the documents say.

Corporate documents from Dali indicate that the company works closely with state-owned Chinese defense contractors and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

Dali will be obligated to complete its work on the Sansha 1 and Sansha 2 within three months of signing its contract with Sansha City, the bidding documents say.

Picture of the DLS-16T Long-Distance Optoelectronic Monitoring System from Dali’s website.

Military-civil fusion

China has a long track record of utilizing civilian ships like the Sansha 1 and Sansha 2 to assert control over the South China Sea.

Devin Thorne, a Washington D.C.-based analyst, told RFA that “there are a few ways that China’s civilian fleets contribute to national security as part of military-civil fusion,” referencing China’s strategy of synthesizing resources to simultaneously advance both defense and development goals.

“They help assert China’s maritime rights by simply being active in disputed areas, they facilitate military power projection, and they extend Beijing’s eyes and ears throughout the near seas,” Thorne said.

For example, the Chinese government has installed the BeiDou satellite navigation system — which has built-in texting capabilities — on thousands of fishing boats to enable these vessels to carry out maritime surveillance in the South China Sea, Chinese documents show.

On top of leveraging ordinary fishermen, China also deploys professionalized maritime militia forces to monitor contested areas.

Satellite image from March 25, 2021 showing roughly two hundred Chinese fishing or militia vessels at Whitsun Reef in the Spratly Islands. Image: Planet Labs.

Thorne told RFA that “the fishing vessels of the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia are best suited for carrying out reconnaissance missions given their training in intelligence gathering and ability to covertly linger for long periods in disputed maritime spaces.”

“But since at least 2014, some maritime militias have started enlisting heavy industrial vessels as well. Their role appears to be providing logistics support and conducting reconnaissance missions during military operations,” Thorne explained.

Thorne added that “China’s civilian fleets are also used to apply pressure in territorial disputes and, in some cases, instigate conflict.”

For instance, the presence of over two hundred Chinese fishing or maritime militia vessels at Whitsun Reef in the Spratly Islands sparked a diplomatic showdown between Manila and Beijing in late March, RFA-affiliated news service BenarNews reported.

“Fishing fleets are most frequently at the forefront of this activity.

However, during the 2014 HYSY 981 standoff we also saw China’s state-owned merchant marine chase, ram, and spray Vietnamese ships,” Thorne said.

“I am not aware of another instance in which China has used the merchant marine like this, but the maritime militia and other parts of China’s armed forces have continued to create linkages with industrial fleets. It could happen again,” Thorne warned.

“I am not aware of another instance in which China has used the merchant marine like this, but the maritime militia and other parts of China’s armed forces have continued to create linkages with industrial fleets. It could happen again,” Thorne warned.

Links :

- CIMSEC : Riding a new wave of professionalization and militarization : Sansha city's maritime militia / China's maritime militia and fishing fleet : a primer for operational staffs and tactical leaders (part 1 / part 2)

- CNN : Beijing has a navy it doesn't even admit exists, experts say. And it's swarming parts of the South China Sea

- Maritime Executive : How Organized is China's Maritime Militia?

- GeoGarage blog : With swarms of ships, Beijing tightens Its grip on South China Sea

Monday, April 12, 2021

The rice of the sea: how a tiny grain could change the way humanity eats

Chef Ángel León found eelgrass seeds have 50% more protein than rice – and the plant stores carbon far faster than a rainforest.

Photograph: Álvaro Fernández Prieto/Aponiente

But then he discovered something in the seagrass that could transform our understanding of the sea itself – as a vast garden

Growing up in southern Spain, Ángel León paid little attention to the meadows of seagrass that fringed the turquoise waters near his home, their slender blades grazing him as he swam in the Bay of Cádiz.

It was only decades later – as he was fast becoming known as one of the country’s most innovative chefs – that he noticed something he had missed in previous encounters with Zostera marina: a clutch of tiny green grains clinging to the base of the eelgrass.

His culinary instincts, honed over years in the kitchen of his restaurant Aponiente, kicked in.

Growing up in southern Spain, Ángel León paid little attention to the meadows of seagrass that fringed the turquoise waters near his home, their slender blades grazing him as he swam in the Bay of Cádiz.

It was only decades later – as he was fast becoming known as one of the country’s most innovative chefs – that he noticed something he had missed in previous encounters with Zostera marina: a clutch of tiny green grains clinging to the base of the eelgrass.

His culinary instincts, honed over years in the kitchen of his restaurant Aponiente, kicked in.

Could this marine grain be edible?

Lab tests hinted at its tremendous potential: gluten-free, high in omega-6 and -9 fatty acids, and contains 50% more protein than rice per grain, according to Aponiente’s research.

Lab tests hinted at its tremendous potential: gluten-free, high in omega-6 and -9 fatty acids, and contains 50% more protein than rice per grain, according to Aponiente’s research.

And all of it growing without freshwater or fertiliser.

The find has set the chef, whose restaurant won its third Michelin star in 2017, on a mission to recast the common eelgrass as a potential superfood, albeit one whose singular lifecycle could have far-reaching consequences.

The find has set the chef, whose restaurant won its third Michelin star in 2017, on a mission to recast the common eelgrass as a potential superfood, albeit one whose singular lifecycle could have far-reaching consequences.

“In a world that is three-quarters water, it could fundamentally transform how we see oceans,” says León.

“This could be the beginning of a new concept of understanding the sea as a garden.”

It’s a sweeping statement that would raise eyebrows from anyone else.

It’s a sweeping statement that would raise eyebrows from anyone else.

But León, known across Spain as el Chef del Mar (the chef of the sea), has long pushed the boundaries of seafood, fashioning chorizos out of discarded fish parts and serving sea-grown versions of tomatoes and pears at his restaurant near the Bay of Cádiz.

The tiny grains within the eelgrass.

The plant is capable of capturing carbon 35 times faster than tropical rainforests.

Photograph: Álvaro Fernández Prieto/Aponiente

“When I started Aponiente 12 years ago, my goal was to open a restaurant that served everything that has no value in the sea,” he says.

“The first years were awful because nobody understood why I was serving customers produce that nobody wanted.”

Still, he pushed forward with his “cuisine of the unknown seas”.

Still, he pushed forward with his “cuisine of the unknown seas”.

His efforts to bring little-known marine species to the fore were recognised in 2010 with his first Michelin star.

By the time the restaurant earned its third star, León had become a fixture on Spain’s gastronomy scene: a trailblazing chef determined to redefine how we treat the sea.

What León and his team refer to as “marine grain” expands on this, in one of his most ambitious projects to date.

What León and his team refer to as “marine grain” expands on this, in one of his most ambitious projects to date.

After stumbling across the grain in 2017, León began looking for any mention of Zostera marina being used as food.

He finally found an article from 1973 in the journal Science on how it was an important part of the diet of the Seri, an Indigenous people living on the Gulf of California in Sonora, Mexico, and the only known case of a grain from the sea being used as a human food source.

Next came the question of whether the perennial plant could be cultivated.

Next came the question of whether the perennial plant could be cultivated.

In the Bay of Cádiz, the once-abundant plant had been reduced to an area of just four sq metres, echoing a decline seen around the world as seagrass meadows reel from increased human activity along coastlines and steadily rising water temperatures.

Working with a team at the University of Cádiz and researchers from the regional government, a pilot project was launched to adapt three small areas across a third of a hectare (0.75 acres) of salt marshes into what León calls a “marine garden”.

It was not until 18 months later – after the plants had produced grains – that León steeled himself for the ultimate test, said Juan Martín, Aponiente’s environmental manager.

Working with a team at the University of Cádiz and researchers from the regional government, a pilot project was launched to adapt three small areas across a third of a hectare (0.75 acres) of salt marshes into what León calls a “marine garden”.

It was not until 18 months later – after the plants had produced grains – that León steeled himself for the ultimate test, said Juan Martín, Aponiente’s environmental manager.

Salt marshes near Cádiz were used to create a ‘marine garden’ where the eelgrass seeds could be sown. Photograph: Álvaro Fernández Prieto/Aponiente

“Ángel came to me, his tone very serious, and said: ‘Juan, I would like to have some grains because I have no idea how it tastes. Imagine if it doesn’t taste good,’” says Martín.

“It’s incredible. He threw himself into it blindly, invested his own money, and he had never even tried this marine grain.”

León put the grain through a battery of recipes, grinding it to make flour for bread and pasta and steeping it in flavours to mimic Spain’s classic rice dishes.

“It’s interesting. When you eat it with the husk, similar to brown rice, it has a hint of the sea at the end,” says León.

León put the grain through a battery of recipes, grinding it to make flour for bread and pasta and steeping it in flavours to mimic Spain’s classic rice dishes.

“It’s interesting. When you eat it with the husk, similar to brown rice, it has a hint of the sea at the end,” says León.

“But without the husk, you don’t taste the sea.”

He found that the grain absorbed flavour well, taking two minutes longer to cook than rice and softening if overcooked.

In the marine garden, León and his team were watching as the plant lived up to its reputation as an architect of ecosystems: transforming the abandoned salt marsh into a flourishing habitat teeming with life, from seahorses to scallops.

The plant’s impact could stretch much further.

In the marine garden, León and his team were watching as the plant lived up to its reputation as an architect of ecosystems: transforming the abandoned salt marsh into a flourishing habitat teeming with life, from seahorses to scallops.

The plant’s impact could stretch much further.

Capable of capturing carbon 35 times faster than tropical rainforests and described by the WWF as an “incredible tool” in fighting the climate crisis, seagrass absorbs 10% of the ocean’s carbon annually despite covering just 0.2% of the seabed.

News of what León and his team were up to soon began making waves around the world.

News of what León and his team were up to soon began making waves around the world.

“When I first heard of it, I was going ‘Wow, this is very interesting,’” says Robert Orth, a professor at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, who has spent more than six decades studying seagrass.

“I don’t know of anyone that has attempted to do what this chef has done.”

We’ve opened a window.

We’ve opened a window.

It's a new way to feed ourselves

According to Orth, seagrass has been used as insulation for houses, roofing material and even for packing seafood, but never cultivated as food.

According to Orth, seagrass has been used as insulation for houses, roofing material and even for packing seafood, but never cultivated as food.

It is an initiative riddled with challenges.

Wild seagrass meadows have been dying off at an alarming rate in recent decades, while few researchers have managed to successfully transplant and grow seagrass, he says.

In southern Spain, however, the team’s first marine garden suggests potential average harvests could be about 3.5 tonnes a hectare.

In southern Spain, however, the team’s first marine garden suggests potential average harvests could be about 3.5 tonnes a hectare.

While the yield is about a third of what one could achieve with rice, León points to the potential for low-cost and environmentally friendly cultivation.

“If nature gifts you with 3,500kg without doing anything – no antibiotics, no fertiliser, just seawater and movement – then we have a project that suggests one can cultivate marine grain.”

A pilot project was successful in cultivating seagrass and obtaining grains that Ángel León then tried in different recipes.

Photograph: www.mapdigital.es

The push is now on to scale up the project, adapting as much as five hectares of salt marshes into areas for cultivating eelgrass.

Every success is carefully tracked, in hopes of better understanding the conditions – from water temperature to salinity – that the plant needs to thrive.

While it is likely to be years before the grain becomes a staple at Aponiente, León’s voice rises with excitement as he considers the transformative possibility of Zostera marina’s minuscule, long-overlooked grain – and its reliance on only seawater for irrigation.

While it is likely to be years before the grain becomes a staple at Aponiente, León’s voice rises with excitement as he considers the transformative possibility of Zostera marina’s minuscule, long-overlooked grain – and its reliance on only seawater for irrigation.

“In the end, it’s like everything,” he says.

“If you respect the areas in the sea where this grain is being grown, it would ensure humans take care of it. It means humans would defend it.”

He and his team envision a global reach for their project, paving the way for people to harness the plant’s potential to boost aquatic ecosystems, feed populations and fight the climate crisis.

He and his team envision a global reach for their project, paving the way for people to harness the plant’s potential to boost aquatic ecosystems, feed populations and fight the climate crisis.

“We’ve opened a window,” says León.

“I believe it’s a new way to feed ourselves.”

Links :

Links :

Sunday, April 11, 2021

Dancing with danger

Surfer Kipp Caddy has spent the last 10 years chasing a dream.

Early in 2020, right before the world went a little crazy, Kipp caught what some of the local guys are calling "One of, if not the craziest wave ever made at Shipsterns Bluff."

Cinematographer Chris Bryan was in the perfect position to capture the moment at 1,000 frames per second.

A wave of a life time and the spectacular results are now being shown for the first time.