View of Mayotte island coast, 10 avril 2014

© AFP/Archives/Sophie Lautier

On November 11, 2018, a deep rumble ricocheted around the world, one that humans couldn’t feel but that registered quite clearly on seismometers.

A new pre-print paper about the event is now suggesting that it was caused by the largest offshore volcanic event in recorded history.

Mayotte island with the GeoGarage platform (SHOM nautical chart)

Originating 30 miles east of the island of Mayotte, near Madagascar, the mid-November signal immediately caught the attention of a disparate group of geoscientists.

They subsequently took to Twitter to express their fascination over this mysterious event—one even joked about a “giant prehistoric sea monster.”

Source

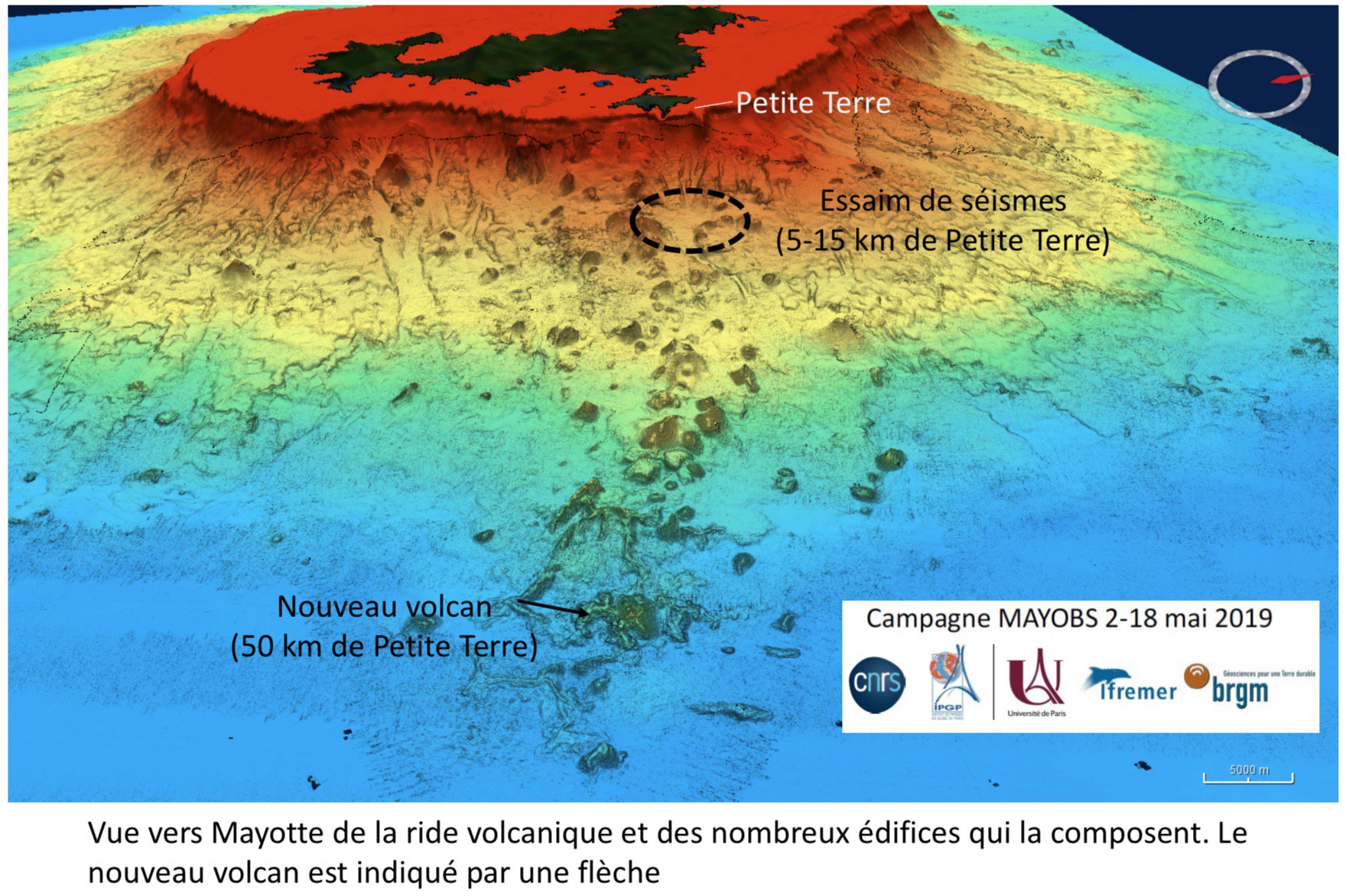

of prolonged Mayotte earthquake swarm identified: new active volcano

discovered 3.5km below sea surface, 0.8km high and 4-5km diameter.

Fluid release reaches 2km above volcano.

The rumble formed part of a prolonged seismic sequence that had started in the area back in May 2018, but the very low-frequency, potent growl in November stood out because it wasn’t immediately obvious what caused it.

These scientists eventually agreed that it could only have originated from a volcanic event, one involving the movement of a vast volume of magma beneath the seafloor, causing the ground there to significantly deflate.

Now, a new paper by researchers at the French Geological Survey and France’s Ecole Normale Supérieure has been uploaded to the public server EarthArXiv.

Although there are plenty of unanswered questions, this first-order estimation of what happened between May and mid-November matches up with the calculations of those geoscientists that took to social media.

In fact, the volume of magma involved is so huge that this is certainly one of the largest offshore volcanic events to be spotted by modern scientific instrumentation.

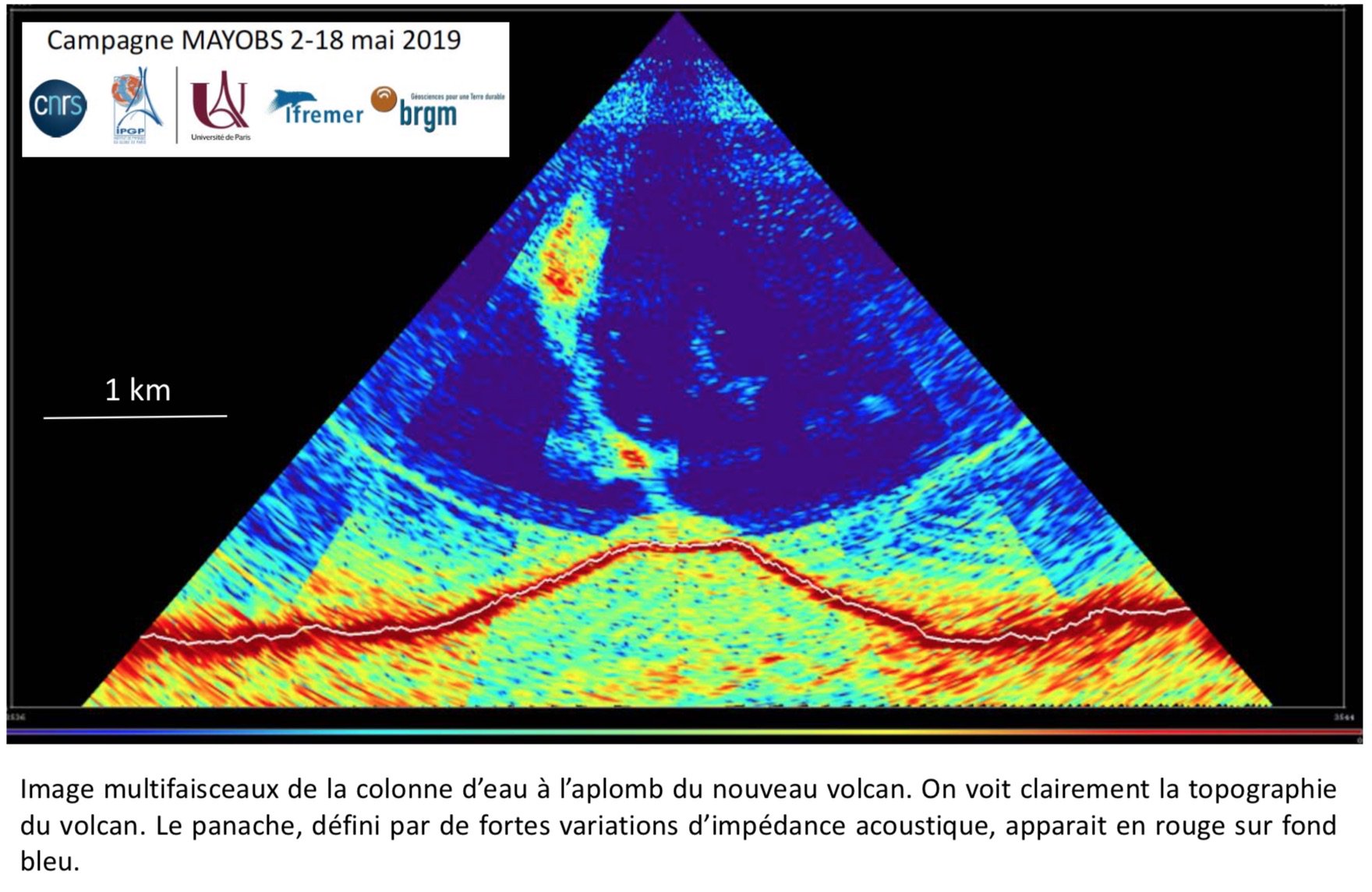

Another

amazing view, in section, of the newly discovered active volcano 50km

offshore Mayotte Topography of the volcanic edifice and the rising fluid

column above it are clearly imaged.

Fluid column is ~2km high but do not reach the surface.

There is a major caveat to all this, however.

Compared to land-based monitoring, there’s a huge lack of offshore monitoring happening around the world today, and there are likely plenty of offshore events that have taken place since modern records began that scientists haven’t picked up on.

Make no mistake, though: The recent event offshore from Mayotte, which is still ongoing, is colossal.

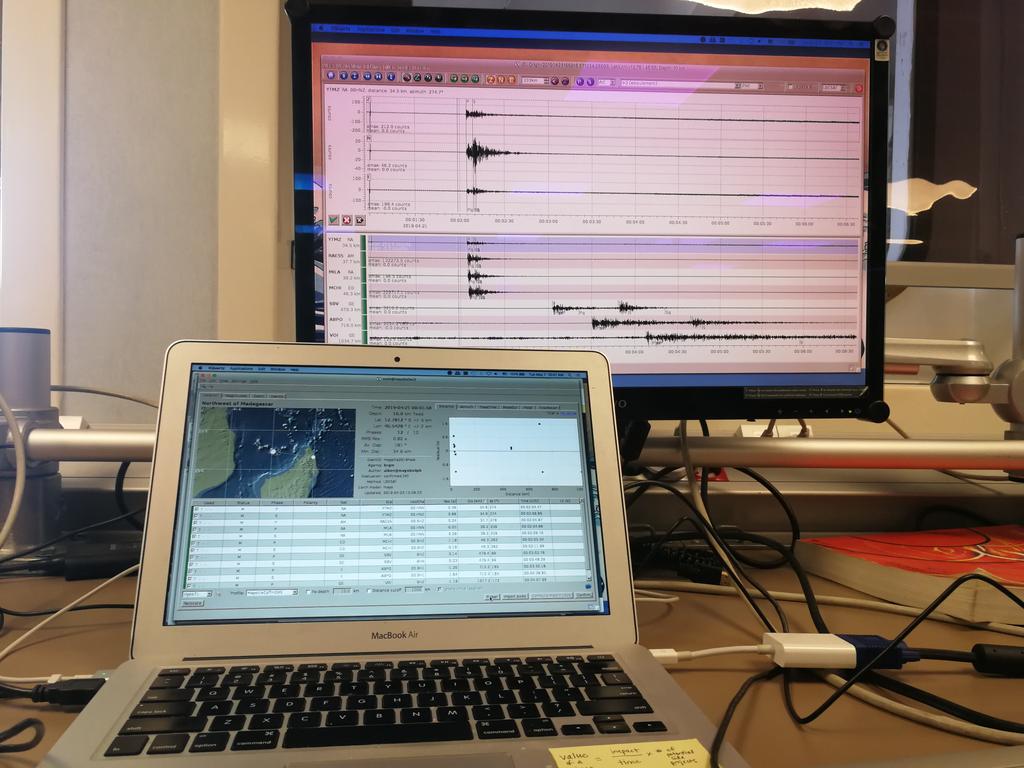

Previous internet detection in Mayotte Region

10 min ago is confirmed by seismic signal

The way the ground on Mayotte is moving implies that the seafloor off its eastern shoreline is sinking at a rate of around 0.4 inches per month.

At the same time, Mayotte itself is shifting eastward at a rate of 0.63 inches per month.

Both indicate something huge underground is on the move, causing some serious deflation.

The nature of these tremors suggest that the magmatic source is centered at a depth of 16 miles beneath the seafloor.

In the first six months of the sequence alone, at least 0.24 cubic miles of magma has shifted around.

That’s roughly equivalent to 385 Great Pyramids of Giza.

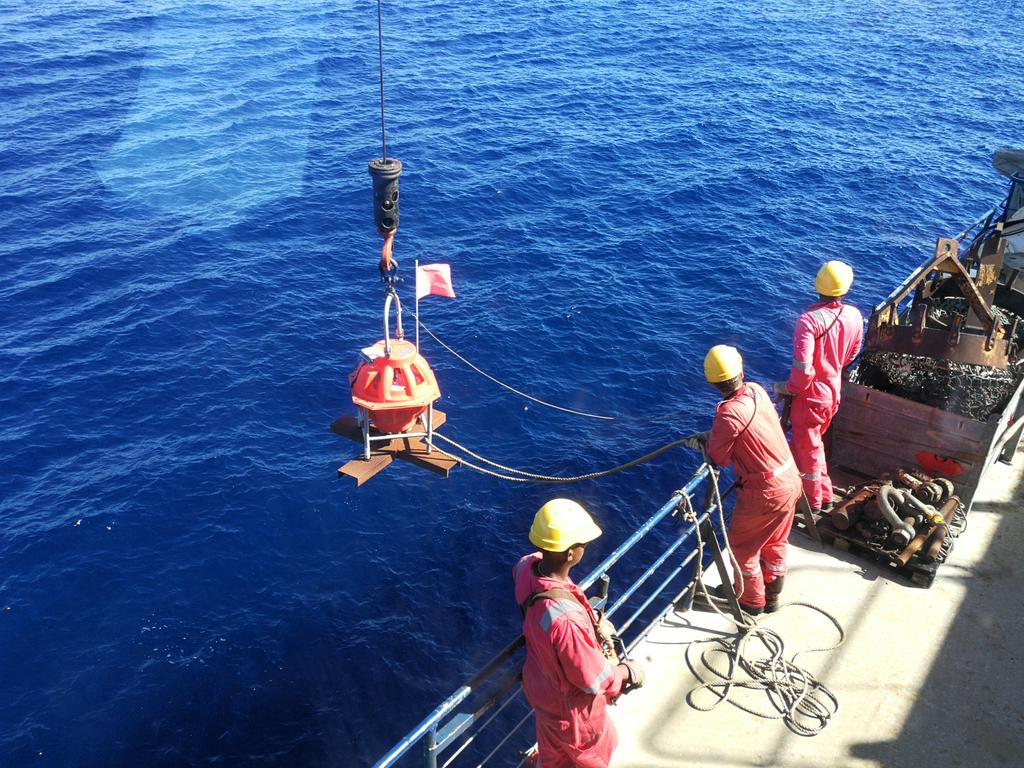

Last working day of MAYOBS cruise on the Marion Dufresne.

In

total, we collected 6 OBS, relocated ~700 events, deployed 14 OBS,

conducted 5 dredges, took 5 water column samples, collected plume data,

and collected bathymetry and chirp data within 2 weeks

Helen Robinson, a geothermal expert and PhD candidate at Glasgow University, compared it to volumes of other submarine eruptions.

From the 1998 Axial Seamount eruption offshore from Oregon, to the Havre paroxysm north of New Zealand on the Kermadec arc, “it certainly seems this is the largest submarine event in terms of volume on record,” she told Gizmodo.

Samuel Mitchell, an expert in underwater eruptions at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa, and who worked on the Havre eruption, agreed that the amounts of volcanic material involved are definitely comparable.

“The 2018 event at Mayotte does appear to show a substantial volume of magma leaving a deep storage region which, if erupted, would make this indeed one of the largest recent submarine eruptions documented,” he said.

That’s a big “if,” though.

As Robinson also points out, and as the new pre-print paper acknowledges, what’s happening near Mayotte is not necessarily an eruption.

Pierre Briole, a geophysicist at France’s Ecole Normale Supérieure and one of the authors of the pre-print, told Gizmodo that the indirect evidence means that he’s “pretty sure it’s an eruption.

” But as there is currently no direct evidence of an eruption having taken place, “there is a significant probability that no lava reached the surface.”That the low-frequency rumble spread across the world was probably due to a “perfect storm.”

Failing to breach into the sea, the migrating magma might have injected itself into thick sediments in the seafloor and spread itself around.

Mitchell explained that this has been observed elsewhere, when the magma is denser than the surrounding sediment.

Although the overall volume of magma involved is comparable to the 2012 Havre eruption, the two are likely to be quite different events.

The former definitely involved plenty of eruptive material, whose huge pumice raft was first spotted from a plane.

At the same time, large, gloopy volcanic domes formed on the seafloor.

In Mayotte’s case, if an eruption did take place, Mitchell explained, it’s more likely to be some sort of fissure effusion involving more fluid lava, a bit like an underwater version of what happened on the slopes of Hawaii’s Kīlauea in 2018.

Jean Paul Ampuero, a seismologist and director of research at France’s Research Institute for Development, told Gizmodo that “this whole sequence is record-breaking in many aspects.” Along with the huge volume of magma, the November 11 signal was also easily one of the largest low-frequency tremors of its kind.

That the low-frequency rumble spread across the world was probably due to a “perfect storm,” according to Stephen Hicks, a seismologist at the University of Southampton.

In this case, that meant having both a very large source and vibrations at the exact right pitch to carry them across a considerable distance.

The November 11 signal’s individual elements still remain deeply puzzling.

In particular, its repeated high-frequency bursts, which are similar (but aren’t related to) industrial activity, are difficult to explain.

Ampuero said that they fall into a timing pattern that indicates they are strongly connected to the low-frequency pulses, indicating the two components “are talking to each other in some way.”

One highly speculative explanation is that the high-frequency events are related to the collapse of the rocky walls surrounding the magmatic monster.

This disturbs the magma reservoir, causing it to oscillate or ‘hum.’ At the same time, waves bouncing back and forth hit other flanks and trigger more collapses, generating more high-frequency events.

This all happens, Ampuero suggests, in a way that causes the low- and high-frequency events to synchronize, forming the November 11 signal.

It’s very difficult to say for sure.

Some smaller tremors in the sequence also had a similar signal, Ampuero added, so “perhaps they’ll catch another one” like the big tremor and take it apart to see what it’s made of.

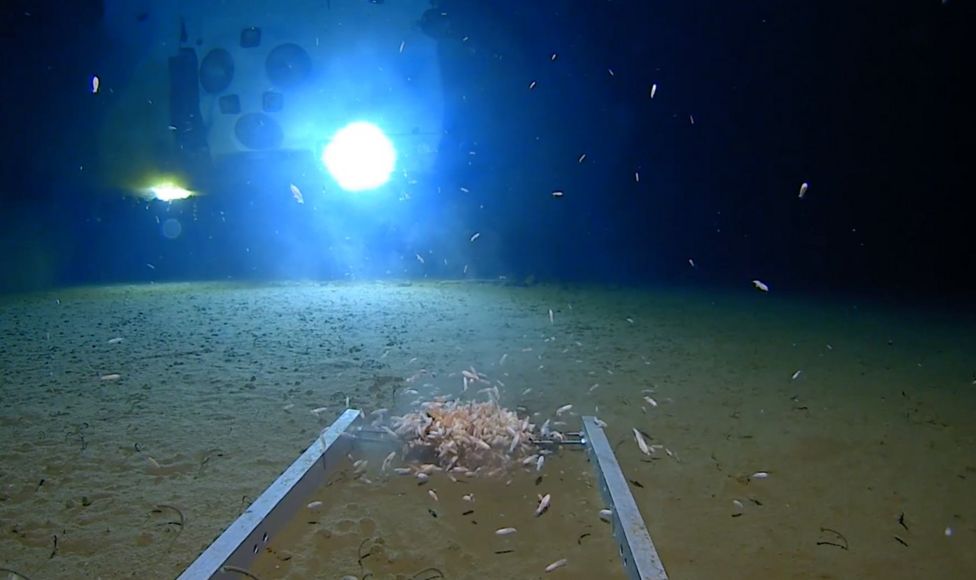

There’s another element to the story that’s currently unexplained: the emergence of lots of dead fish offshore from Mayotte.

The earthquake swarm (BRGM)

This major volcanic event is taking place on the eastern end of the island chain, whereas the youngest volcanic islands are to the west.

So it appears to be happening in the ‘wrong’ place.

It’s also unclear what’s responsible for the volcanism in the first place.

It could be caused by action along a tectonic plate boundary, an upwelling plume of superheated mantle material, or even an extension of the East African Rift, a major tectonic event that’s slowly tearing the continent apart, said Hicks.

There is even an ecological element to the story that’s currently unexplained: the emergence of lots of dead fish offshore from Mayotte.

Volcanic gases can suffocate sea life during eruptions, but the pre-print reports that the gases remained trapped in the magma.

Briole has heard unverified reports that the fish that died were deep-sea fish.

The magmatic activity might have scared them up to the surface, where they experienced low pressures that they couldn’t survive in.

Robinson said that the magma, which may have intruded into seafloor sediments, cooked those sediments and released carbon dioxide into the water column, which could also have asphyxiated those deep-sea fish.

Like much about the event, this remains speculative for now.

Clearly more instrumentation is required, and the French National Centre for Scientific Research—with help from the BRGM and other authorities—are now deploying plenty.

This includes equipment on Mayotte, at the site of the activity, and on the Glorioso Islands to the east, so that they can ‘listen’ to the disturbances from the other side.

That still won’t solve all the enigmas.

Mitchell pointed out that underwater drones and ship-based radar surveys will be required to determine how much lava erupted at the surface, if any, and Hicks suggested that numerical simulations and laboratory work may be required to better comprehend what’s going on beneath the surface.

As Ampuero emphasizes, this isn’t just about scratching a scientific itch, but helping out the local communities, too.

“The people in Mayotte really want to know what’s going to happen next,” he said.

As a recent report on the situation notes, there is often an atmosphere of confusion and distrust on the island.

The more research that’s conducted, the better off everyone will be.

Links :

- AfricaTimes :Scientists look for answers as Mayotte quake swarm marks 1-year milestone

- National Geographic : Strange waves rippled around the world, and nobody knows why

- The Guardian : 'Magma shift' may have caused mysterious seismic wave event