Richard Liu, CEO and founder of China's e-commerce company JD.com

The announcement of the creation of the Sea Expandary shipyard in China, backed by an investment of around $700 million, goes beyond the simple launch of a new player aiming to establish itself in the yachting industry and then in recreational boating.

A yacht like a car? http://JD.com founder Liu Qiangdong launched Sea Expandary, a solo venture backed by 5 billion RMB ($690M) of his personal funds. The goal? To disrupt the luxury status quo. Liu aims to mass-produce spacious, high-quality yachts for as low as 100,000 RMB ($14,000)—making yachting as accessible as owning a car.

It is reminiscent of a scenario already seen in the automotive industry.

And the question deserves to be asked for European and American recreational boating.

From Pulse by Wei XIE

In my previous post, I shared my take on the 'dreamy' narrative of the 100,000-yuan yacht.

Now, let's dive into Sea Expandary's dual-track strategy.

Short-term (high-net-worth clients): The initial product line targets 60-120-foot mid-to-large luxury yachts, catering to corporate clients and high-net-worth individuals. This segment aims to accelerate capital recovery and establish brand premium. However, Sea Expandary holds virtually no competitive edge in the 60-120-foot luxury yacht market. The "short-term premium" component of its "dual-track strategy" appears more like a transitional narrative device than a viable commercial approach.

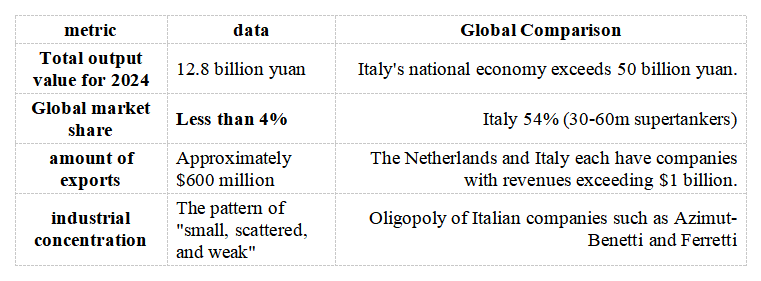

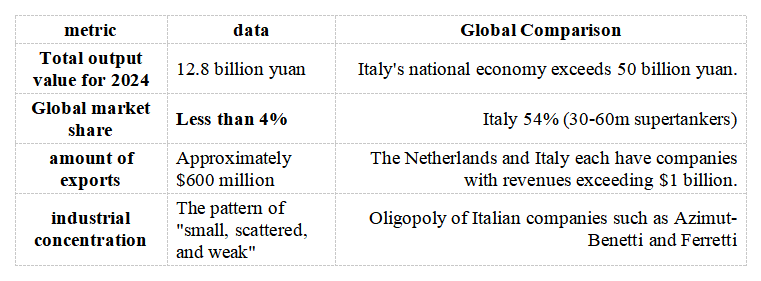

I.The " Small,Scattered and Weak"status of domestic yacht industry

China's shipbuilding industry accounts for 55.7%-74.1% of the global merchant ship market share, but is completely silent in the "small boat" sector of yachts. This is not a problem of manufacturing capacity, but a comprehensive lag in branding, design, and experience definition.

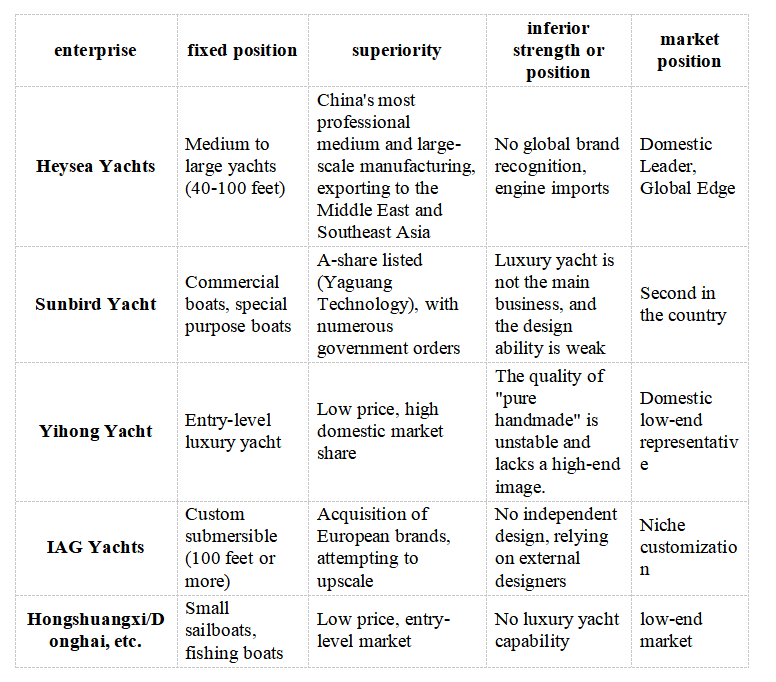

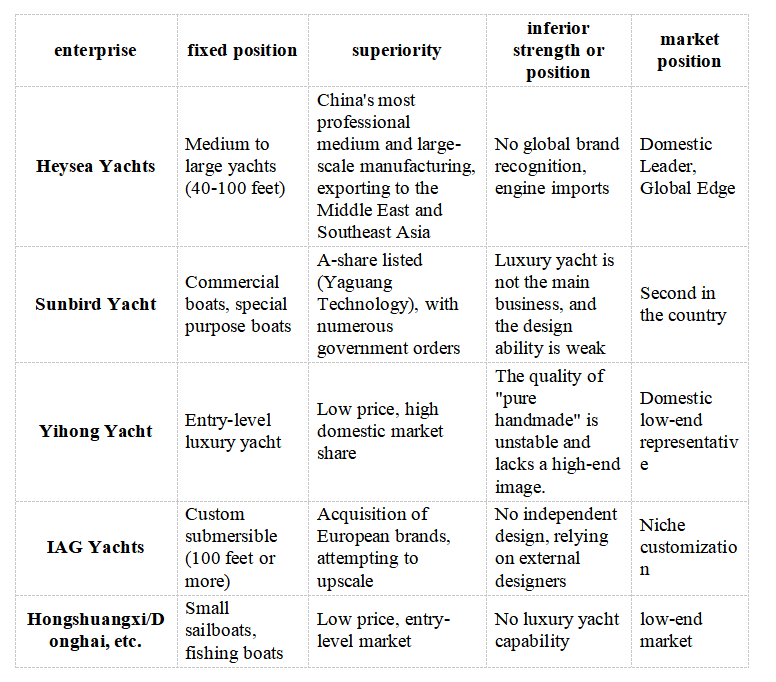

II. Competitiveness Analysis of Existing Domestic Players

Major domestic yacht manufacturers

Common weaknesses:

-Engine: 100% imported from Yamaha, Mercury, Volvo and other brands

-Design: No internationally renowned designer involved, with exterior and interior styling inspired by European aesthetics

-Brand: Without centuries of heritage, it cannot enter the high-end circles of Europe and America

-Certification: No International Yacht Association (IYBA) top-tier certification

III. Dissecting the "Advantages" of Sea Expandary: Story vs Reality

Advantage vs. real competitiveness

Short-term (high-net-worth clients): The initial product line targets 60-120-foot mid-to-large luxury yachts, catering to corporate clients and high-net-worth individuals. This segment aims to accelerate capital recovery and establish brand premium. However, Sea Expandary holds virtually no competitive edge in the 60-120-foot luxury yacht market. The "short-term premium" component of its "dual-track strategy" appears more like a transitional narrative device than a viable commercial approach.

I.The " Small,Scattered and Weak"status of domestic yacht industry

China's shipbuilding industry accounts for 55.7%-74.1% of the global merchant ship market share, but is completely silent in the "small boat" sector of yachts. This is not a problem of manufacturing capacity, but a comprehensive lag in branding, design, and experience definition.

II. Competitiveness Analysis of Existing Domestic Players

Major domestic yacht manufacturers

Common weaknesses:

-Engine: 100% imported from Yamaha, Mercury, Volvo and other brands

-Design: No internationally renowned designer involved, with exterior and interior styling inspired by European aesthetics

-Brand: Without centuries of heritage, it cannot enter the high-end circles of Europe and America

-Certification: No International Yacht Association (IYBA) top-tier certification

III. Dissecting the "Advantages" of Sea Expandary: Story vs Reality

Advantage vs. real competitiveness

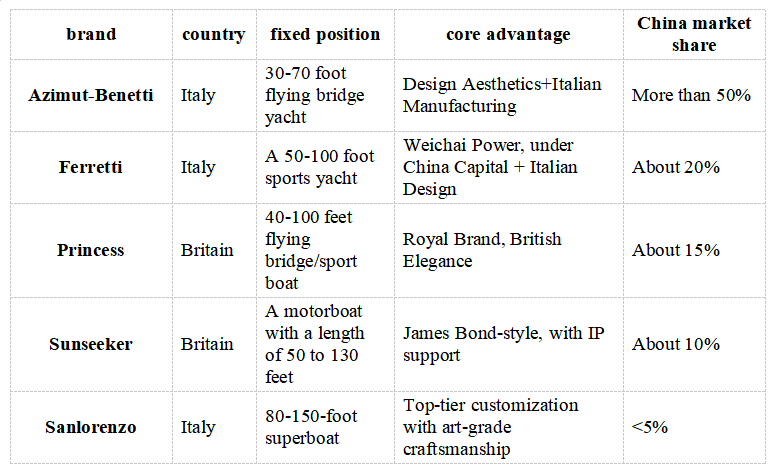

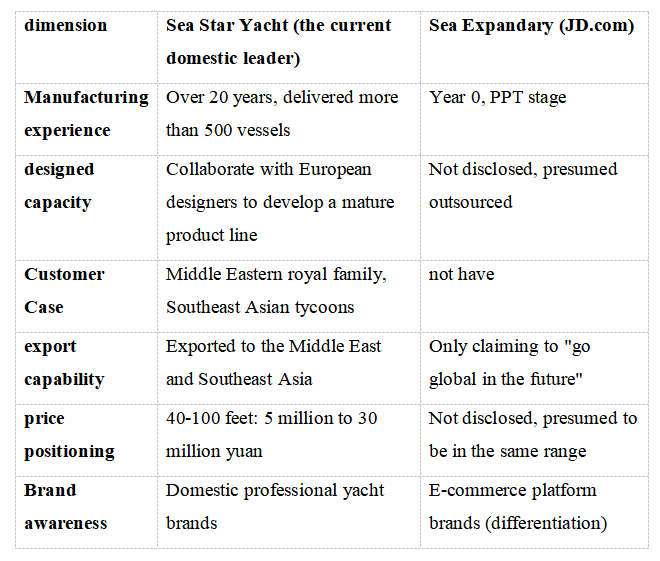

IV. The Real Competitive Landscape in the High-End Market

60-120 ft luxury yacht: Monopolized by European oligarchs

Sea Expandary's entry space: almost zero

•Technology: No in-house engine R&D capability, requiring imported components

•Design: No internationally renowned designer team

•Brand: JD.com's brand is unrelated to' luxury 'and may even command a premium (as affluent consumers avoid associating it with' express delivery brands').

•Service: No global after-sales service network (European brands have repair centers worldwide)

Ⅴ. Why the "Short-term High-end" Strategy is Unfeasible?

1. Purchase logic of high-end customers

60-120 ft luxury yacht: Monopolized by European oligarchs

Sea Expandary's entry space: almost zero

•Technology: No in-house engine R&D capability, requiring imported components

•Design: No internationally renowned designer team

•Brand: JD.com's brand is unrelated to' luxury 'and may even command a premium (as affluent consumers avoid associating it with' express delivery brands').

•Service: No global after-sales service network (European brands have repair centers worldwide)

Ⅴ. Why the "Short-term High-end" Strategy is Unfeasible?

1. Purchase logic of high-end customers

For high-end clients, purchasing a yacht is about acquiring a status symbol rather than a means of transportation. Sea Expandary fails to deliver the integrated value of Italian design, European craftsmanship, and a century-old brand.

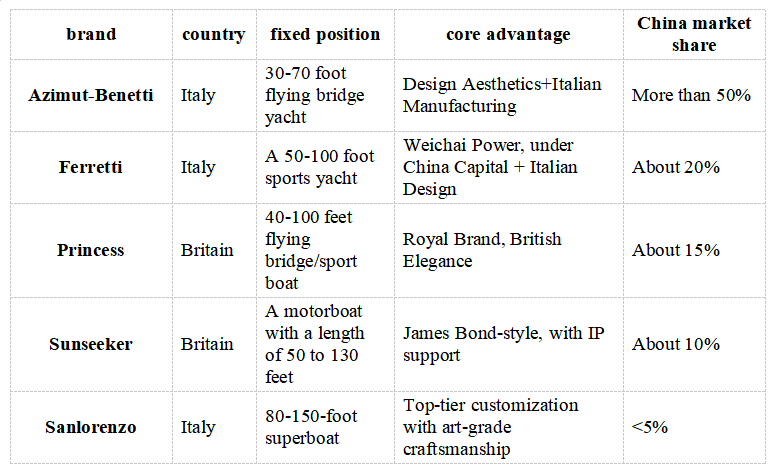

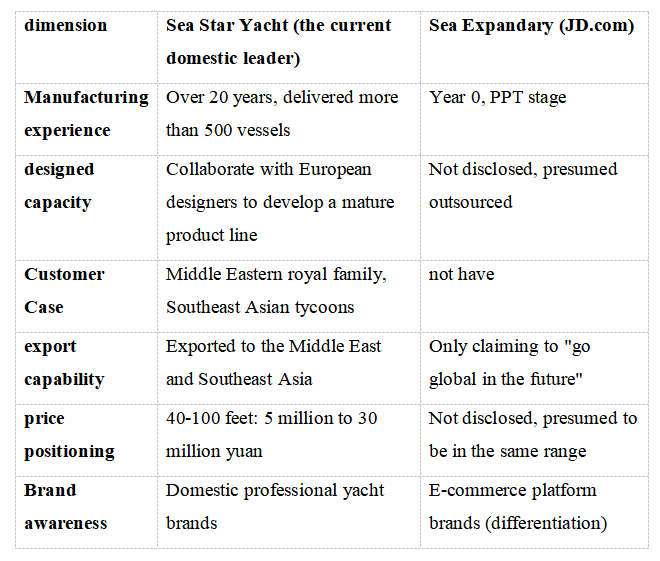

2. Comparison with Domestic Competitors

Sea Expandary's competitive edge over sea stars lies in its' 5 billion yuan capital 'and' Liu Qiangdong's IP,' yet neither translates into tangible product value or brand influence.

VI. The Real Purpose of the "Dual-track Strategy"

2. Comparison with Domestic Competitors

Sea Expandary's competitive edge over sea stars lies in its' 5 billion yuan capital 'and' Liu Qiangdong's IP,' yet neither translates into tangible product value or brand influence.

VI. The Real Purpose of the "Dual-track Strategy"

'Short-term premium' is not a business strategy but a narrative tactic-No actual products (announced in March 2026, with the first ship not yet launched) -No real customers (no orders disclosed) -No genuine competitiveness (completely outpaced by European brands and inexperienced compared to domestic industry leaders)

In the untapped market, Sea Expandary remains a 'blank' area.

The Chinese yacht industry remains a 'blank slate' —lacking global brands, core technologies, and high-end recognition. Yet Sea Expandary has not filled this void, instead repeating JD.com's' follow-the-leader' strategy.

Sea Expandary's so-called' advantages 'in the 60-120-foot luxury yacht market are actually negative: it lacks European brand expertise, design innovation, and established reputation; it falls short of domestic leaders in experience, client base, and team building; its only' strength 'is a 5-billion-yuan investment and Liu Qiangdong's storytelling prowess.

Yet this is precisely the path dependence of underdog success stories: trading capital for time, stories for resources, and following for security. In the luxury yacht industry, which demands original designs, brand equity, and technological breakthroughs, this logic simply doesn't hold water.

As noted by Lu Xiao, Director of the International Premium Brand Strategy Research Institute: "The yacht industry's high value creation lies not merely in steel welding and hardware assembly, but in the fusion of material functionality and spiritual experience." Sea Expandary lacks both differentiated material features (due to immature new energy technology) and the capacity to build spiritual experiences (with zero brand heritage).

The 'short-term premium' strategy is doomed to remain just a transitional slide in a PPT, never evolving into a viable business model.

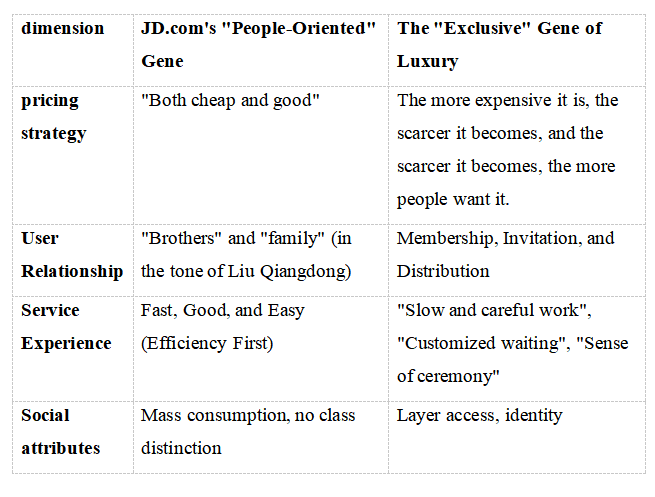

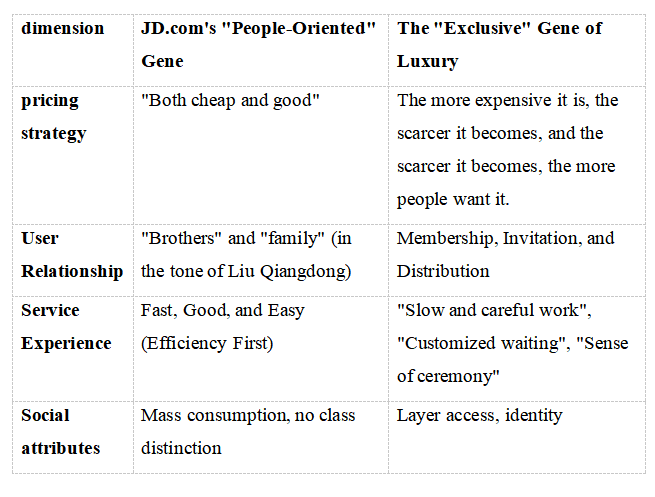

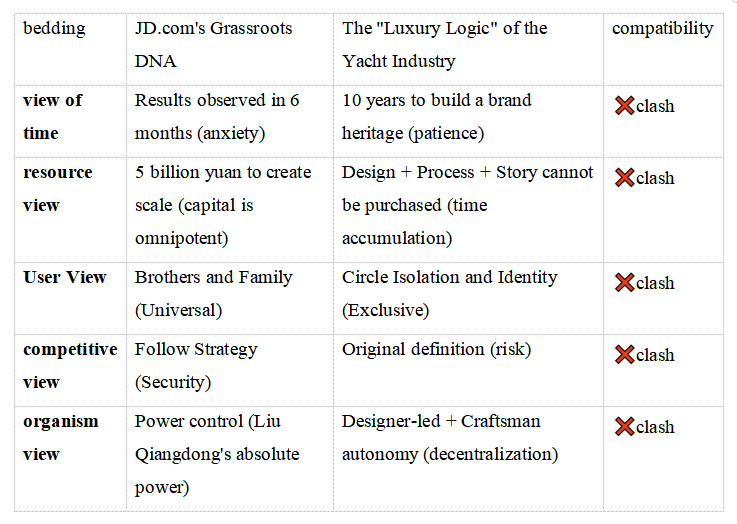

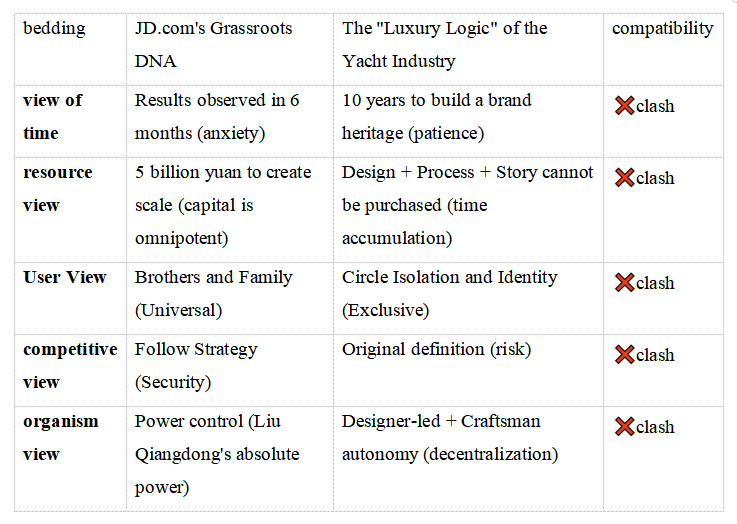

The most important and fundamental point is:The Incompatibility between "Express Brand" and "Luxury"

The "Class Isolation" of Brand Cognition

In the untapped market, Sea Expandary remains a 'blank' area.

The Chinese yacht industry remains a 'blank slate' —lacking global brands, core technologies, and high-end recognition. Yet Sea Expandary has not filled this void, instead repeating JD.com's' follow-the-leader' strategy.

Sea Expandary's so-called' advantages 'in the 60-120-foot luxury yacht market are actually negative: it lacks European brand expertise, design innovation, and established reputation; it falls short of domestic leaders in experience, client base, and team building; its only' strength 'is a 5-billion-yuan investment and Liu Qiangdong's storytelling prowess.

Yet this is precisely the path dependence of underdog success stories: trading capital for time, stories for resources, and following for security. In the luxury yacht industry, which demands original designs, brand equity, and technological breakthroughs, this logic simply doesn't hold water.

As noted by Lu Xiao, Director of the International Premium Brand Strategy Research Institute: "The yacht industry's high value creation lies not merely in steel welding and hardware assembly, but in the fusion of material functionality and spiritual experience." Sea Expandary lacks both differentiated material features (due to immature new energy technology) and the capacity to build spiritual experiences (with zero brand heritage).

The 'short-term premium' strategy is doomed to remain just a transitional slide in a PPT, never evolving into a viable business model.

The most important and fundamental point is:The Incompatibility between "Express Brand" and "Luxury"

The "Class Isolation" of Brand Cognition

The Core Logic of Luxury: Distance and Exclusion

"Luxury goods must be priced high enough to exclude the wrong crowd" — Hermès' former CEO

The core conflict lies in the fundamental difference between JD.com's 20-year philosophy of' efficiency for all 'and the' social stratification' mindset required by the yacht industry.

The Real Psychology of the Rich: What to Buy vs What to Skip

China high net worth individuals' yacht purchase decisions

"Luxury goods must be priced high enough to exclude the wrong crowd" — Hermès' former CEO

The core conflict lies in the fundamental difference between JD.com's 20-year philosophy of' efficiency for all 'and the' social stratification' mindset required by the yacht industry.

The Real Psychology of the Rich: What to Buy vs What to Skip

China high net worth individuals' yacht purchase decisions

Real-scene simulation:

Sanya Yacht Club: A conversation between rich man A and rich man B

A: "Just ordered an Azimut 72, an Italian-designed vessel with a Volvo engine, scheduled to sail to the Xisha Islands next week."

B: "That's great! I bought a new energy vehicle from JD with AI driving—it'll save me a fortune on fuel over the next 10 years."

A: (with an awkward smile) "Oh... JD.com does yachts too? That's great! What a great value for money!"

B: (sighing in frustration) "Did I really spend 20 million just to hear you say 'great value for money'?"

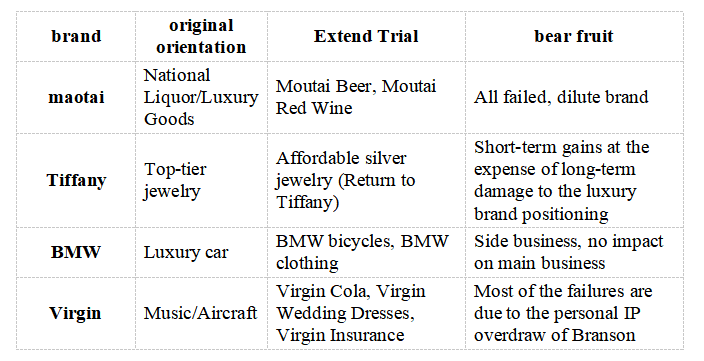

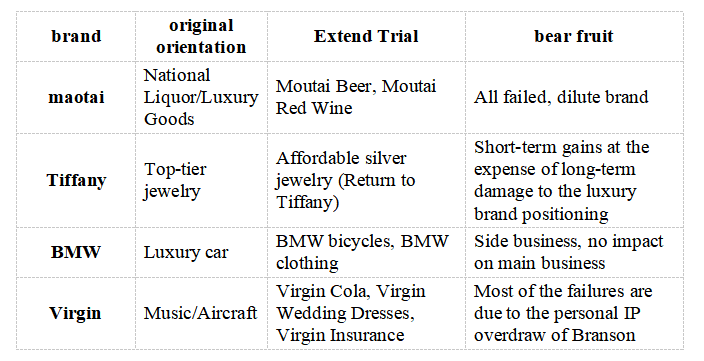

Historical Reference: The "Death Trap" of Brand Extension

Sea Expandary's "No Chance"

I.Nine-dimensional Narrative Matrix Score (Full Score: 10)

Sanya Yacht Club: A conversation between rich man A and rich man B

A: "Just ordered an Azimut 72, an Italian-designed vessel with a Volvo engine, scheduled to sail to the Xisha Islands next week."

B: "That's great! I bought a new energy vehicle from JD with AI driving—it'll save me a fortune on fuel over the next 10 years."

A: (with an awkward smile) "Oh... JD.com does yachts too? That's great! What a great value for money!"

B: (sighing in frustration) "Did I really spend 20 million just to hear you say 'great value for money'?"

Historical Reference: The "Death Trap" of Brand Extension

Sea Expandary's "No Chance"

I.Nine-dimensional Narrative Matrix Score (Full Score: 10)

Overall score: 1.8/10-Lacks any sustainable competitive advantage

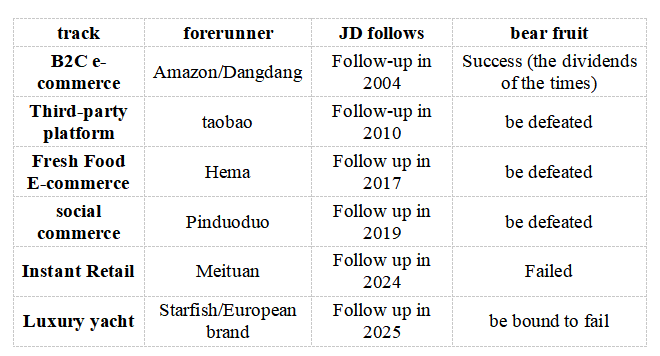

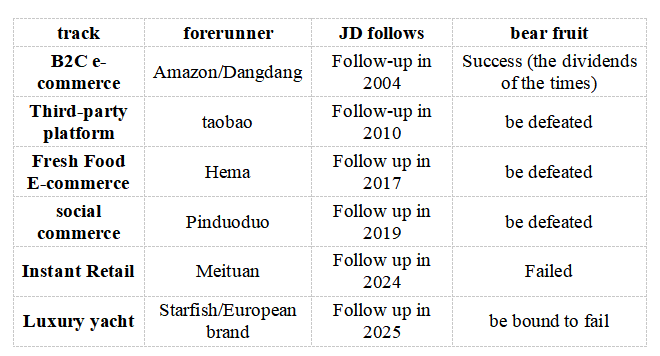

II. Comparison with JD's Past Failed Projects

III. Prediction of the "Evaporation Path" of 5 Billion Yuan

Year 1-2: Storytelling and Financing

── Terminal construction (Shenzhen, Zhuhai): 2 billion yuan (heavy asset, no return)

── Team building + design outsourcing: 500 million (no core capability accumulation)

├── Marketing PR ("China Yacht Dream"): 500 million (public opinion heat = orders)

── First batch of 2-3 prototype ships: 1 billion (no customer orders, purely for display)

Year 3-4: The Story Breaks Down

─ High-end customers have zero orders (brand recognition failure)

── Turn to "Inclusive Yacht" (100,000 Yuan Class), Discover the Paradox of Holding Cost

── New energy technology failures (battery weight increase, range anxiety)

── Policy Subsidy Rollback (The Narrative of Common Prosperity Fails)

Year 5: Liquidation or Transformation

── Asset disposal: Transfer of wharf operation rights (at a discount of 50%)

── Team Dissolution: Lack of Industry Experience and Talent Drain

── Best-case scenario: Integration into JD Logistics (as a "water-based express" pilot project?)

Estimated recovery rate: 20-30% (1-1.5 billion) Estimated net loss: 3.5-4 billion

IV. The Only Possible "Path to Survival" (Probability <5%)

II. Comparison with JD's Past Failed Projects

III. Prediction of the "Evaporation Path" of 5 Billion Yuan

Year 1-2: Storytelling and Financing

── Terminal construction (Shenzhen, Zhuhai): 2 billion yuan (heavy asset, no return)

── Team building + design outsourcing: 500 million (no core capability accumulation)

├── Marketing PR ("China Yacht Dream"): 500 million (public opinion heat = orders)

── First batch of 2-3 prototype ships: 1 billion (no customer orders, purely for display)

Year 3-4: The Story Breaks Down

─ High-end customers have zero orders (brand recognition failure)

── Turn to "Inclusive Yacht" (100,000 Yuan Class), Discover the Paradox of Holding Cost

── New energy technology failures (battery weight increase, range anxiety)

── Policy Subsidy Rollback (The Narrative of Common Prosperity Fails)

Year 5: Liquidation or Transformation

── Asset disposal: Transfer of wharf operation rights (at a discount of 50%)

── Team Dissolution: Lack of Industry Experience and Talent Drain

── Best-case scenario: Integration into JD Logistics (as a "water-based express" pilot project?)

Estimated recovery rate: 20-30% (1-1.5 billion) Estimated net loss: 3.5-4 billion

IV. The Only Possible "Path to Survival" (Probability <5%)

V. Core Conclusion: Why "No Chance of Success"?

Sea Expandary is not a commercial venture, but a narrative-driven storytelling tool: it frames policy narratives through 'common prosperity + new energy', capital narratives via '5 billion yuan investment', and trust-building narratives by leveraging the JD brand.

Yet all three narratives are false: -The public cannot afford it (actual annual cost exceeds 160,000 yuan) -The government sees no need (lacks strategic value, purely consumer-driven) -The brand is untenable (express delivery and luxury are mutually exclusive)

Even if 5 billion ordinary people squandered their wealth, it would take them generations to exhaust it. For Liu Qiangdong, this merely reflects 'fluctuations in trust asset valuations'; but for Shenzhen and Zhuhai governments and potential future shareholders, this represents a genuine wealth transfer. These 5 billion are not 'investment' but 'consumption' —a purchase of a 'captain's dream 'narrative, where the protagonist has already secured a' never-drowning' lifeboat through offshore structures.

Sea Expandary is not a commercial venture, but a narrative-driven storytelling tool: it frames policy narratives through 'common prosperity + new energy', capital narratives via '5 billion yuan investment', and trust-building narratives by leveraging the JD brand.

Yet all three narratives are false: -The public cannot afford it (actual annual cost exceeds 160,000 yuan) -The government sees no need (lacks strategic value, purely consumer-driven) -The brand is untenable (express delivery and luxury are mutually exclusive)

Even if 5 billion ordinary people squandered their wealth, it would take them generations to exhaust it. For Liu Qiangdong, this merely reflects 'fluctuations in trust asset valuations'; but for Shenzhen and Zhuhai governments and potential future shareholders, this represents a genuine wealth transfer. These 5 billion are not 'investment' but 'consumption' —a purchase of a 'captain's dream 'narrative, where the protagonist has already secured a' never-drowning' lifeboat through offshore structures.

Links :

.jpeg)

Photo Credit: The Cradle

Photo Credit: The Cradle