A few miles east of the longitude of the Kerguelen Islands, Biotherm's Onboard Reporter (OBR), Ronan Gladu, took out his drone for our great pleasure.

Saturday, March 11, 2023

Friday, March 10, 2023

Power ships now provide about one quarter of Cuba's electricity

Image courtesy Karpowership

Image courtesy KarpowershipFrom Maritime Executive

The government of Cuba faces tough choices in addressing a chronic shortage of electrical generating capacity, as rolling blackouts have affected communities across the country for months.

The erratic power supply has added to the downward pressure on Cuba's economy, which has been in severe decline - so severe that about two percent of the population tried to leave for the U.S. last year.

The broader issue of economic malaise will be difficult to address, but Havana has at least found a technical way to reduce the impact of the power shortage: floating mobile generating stations, courtesy of Turkish operator Karpowership.

Cuba's relationship with Karadeniz-owned Karpowership began in 2018, when its government signed a four-year charter for three small floating power plants.

Taken together, these units provide about 110 MW of capacity.

As the Cuban utility sector's Cold War-era permanent power plants have deteriorated, Karpowership's share of the nation's grid capacity has gradually gone up.

Karadeniz Powership 'Irem Sultan' with the GeoGarage platform (GeoCuba nautical raster chart)

The eighth unit in Cuba arrived in Havana at the beginning of February, bringing total capacity to roughly 770 MW, or one-quarter of Cuba's minimum electrical demand of 3,000 MW.

The speed of delivery of a powership lends itself well to Cuba's needs.

Cuba's onshore power plants need deep maintenance, and the rapid addition of portable generating capacity makes it easier to take existing plants offline for overhaul.

It's also far faster than building new capacity on shore, which could take years and would require overcoming the structural hurdles to all infrastructure projects in Cuba - like U.S. sanctions and access to capital, among others.

The same obstacles may make it hard for Cuba to pay for the services of Karpowership, according to Al-Arabiya.

"The Cubans do not have any money," said Jorge Pinon, a senior research fellow at UT Austin, in conversation with the outlet.

Cuba's heavy dependence on oil for power generation is partly a quirk of Cold War history.

The Caribbean nation was a Soviet client state for decades, and it built out most of its power generation capacity to run on subsidized Russian fuel oil.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, this relationship ended, and it has struggled to maintain and fuel its fleet of Eastern Bloc-designed thermal power plants ever since.

Under other circumstances, the nation might have become less reliant on fossil fuels.

Towards the end of the Cold War, Cuba nearly built an 880 MW nuclear power station with Soviet assistance.

Construction began in 1983, but the dissolution of the Soviet Union put an end to Russian financing and technical assistance.

The project was abandoned in 1992, and the ruins of the unfinished plant are still visible today.

The speed of delivery of a powership lends itself well to Cuba's needs.

Cuba's onshore power plants need deep maintenance, and the rapid addition of portable generating capacity makes it easier to take existing plants offline for overhaul.

It's also far faster than building new capacity on shore, which could take years and would require overcoming the structural hurdles to all infrastructure projects in Cuba - like U.S. sanctions and access to capital, among others.

The same obstacles may make it hard for Cuba to pay for the services of Karpowership, according to Al-Arabiya.

"The Cubans do not have any money," said Jorge Pinon, a senior research fellow at UT Austin, in conversation with the outlet.

Cuba's heavy dependence on oil for power generation is partly a quirk of Cold War history.

The Caribbean nation was a Soviet client state for decades, and it built out most of its power generation capacity to run on subsidized Russian fuel oil.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, this relationship ended, and it has struggled to maintain and fuel its fleet of Eastern Bloc-designed thermal power plants ever since.

Under other circumstances, the nation might have become less reliant on fossil fuels.

Towards the end of the Cold War, Cuba nearly built an 880 MW nuclear power station with Soviet assistance.

Construction began in 1983, but the dissolution of the Soviet Union put an end to Russian financing and technical assistance.

The project was abandoned in 1992, and the ruins of the unfinished plant are still visible today.

Planta Nuclear de Juraguà with the GeoGarage platform (GeoCuba nautical raster chart)

Links :

Thursday, March 9, 2023

Britain’s plan to stem the flow of asylum-seekers is deeply flawed

From The Economist

Britain’s plan to stem the flow of asylum-seekers is deeply flawed

A new law to “stop the boats” is unlikely to work

Britain’s plan to stem the flow of asylum-seekers is deeply flawed

A new law to “stop the boats” is unlikely to work

“Stopping the boats” is one of Rishi Sunak’s five promises for 2023.

More than 45,000 small-boat migrants crossed the English Channel last year, exposing Britain’s inability to control its borders.

That figure was expected to grow this year.

Mr Sunak and Suella Braverman, the home secretary, have now come up with a plan.

New legislation unveiled on March 7th would render inadmissible asylum claims by those who travel across the English Channel on flimsy dinghies.

Instead, they would almost all be detained and deported, never to return.

Yet it is difficult to imagine how the government’s new Illegal Migration Bill can do much to alleviate the problem.

Detaining asylum-seekers is morally and legally dubious: under international law asylum-seekers cannot be deemed “illegal”.

The Home Office itself acknowledges that many of those who enter Britain in small boats are legitimately in search of sanctuary.

In 2022 migrants from the five countries that accounted for nearly half of those who crossed the Channel had an asylum grant rate of above 80%.

For three nationalities—Afghans, Eritreans and Syrians—it was 98%.

Migrants picked up at sea while attempting to cross the English Channel are pictured on a UK Border Force boat entering the Marina in Dover on April 18, 2022.

© Ben Stansall, AFP

The plan has myriad practical flaws, too.

Britain has no capacity to hold large numbers of detained migrants.

The government’s idea is to deter others from making the journey, thus keeping the numbers locked up and deported manageable.

But it is far from clear that the policy would have this effect.

Or if it did, how long it would take and how many migrants Britain would first have to detain.

The next question is where would these migrants then be deported to?

Britain already has a returns agreement with Albania, which has reduced the number of Albanians claiming asylum.

But it will not be able to strike similar deals with most of the other countries asylum-seekers flee.

That is because it is illegal to return them to countries considered unsafe.

In the absence of a returns agreement with France (which is not in the offing), Britain could not send them back there.

An attempt to use Rwanda as a destination for processing claims and settling those who succeeded is stalled in the courts.

Britain has no other such arrangement with a safe third country.

It seems likely, then, that Britain will continue to process the claims of those who come from countries to which they cannot be returned.

This would echo an earlier failure to tackle the problem.

Under rules introduced in 2022 migrants who arrived in Britain having passed through other safe countries without claiming asylum are classed as “inadmissible”.

Yet immigration lawyers say that has made no actual difference to the way their claims are processed, except to lengthen further the time spent waiting for a decision.

The new law seems likely to have a similar effect, though it may temporarily please some on the right of the Conservative Party.

Critics of this and previous attempts to tackle the small-boats crisis point out that there are few other routes for people fleeing war and persecution to claim asylum in Britain.

There are schemes to reunite refugees with family members, and for Afghans, Hong Kongers and Ukrainians to apply to be resettled (although too few Afghans who helped Britain during its war against the Taliban have been allowed to come to the country).

Asylum-seekers from other countries have no way to travel into Britain except by small boat or lorry.

The government has promised to introduce new safe routes but says it must first fix the small-boats problem.

“That’s the wrong way round,” says Sunder Katwala, director of British Future, a think-tank.

He says that introducing new schemes targeted at certain countries could, along with a returns deal with France, reduce the number of people travelling to Britain in small boats.

The new law will not stop them.

But it will not be able to strike similar deals with most of the other countries asylum-seekers flee.

That is because it is illegal to return them to countries considered unsafe.

In the absence of a returns agreement with France (which is not in the offing), Britain could not send them back there.

An attempt to use Rwanda as a destination for processing claims and settling those who succeeded is stalled in the courts.

Britain has no other such arrangement with a safe third country.

It seems likely, then, that Britain will continue to process the claims of those who come from countries to which they cannot be returned.

This would echo an earlier failure to tackle the problem.

Under rules introduced in 2022 migrants who arrived in Britain having passed through other safe countries without claiming asylum are classed as “inadmissible”.

Yet immigration lawyers say that has made no actual difference to the way their claims are processed, except to lengthen further the time spent waiting for a decision.

The new law seems likely to have a similar effect, though it may temporarily please some on the right of the Conservative Party.

Critics of this and previous attempts to tackle the small-boats crisis point out that there are few other routes for people fleeing war and persecution to claim asylum in Britain.

There are schemes to reunite refugees with family members, and for Afghans, Hong Kongers and Ukrainians to apply to be resettled (although too few Afghans who helped Britain during its war against the Taliban have been allowed to come to the country).

Asylum-seekers from other countries have no way to travel into Britain except by small boat or lorry.

The government has promised to introduce new safe routes but says it must first fix the small-boats problem.

“That’s the wrong way round,” says Sunder Katwala, director of British Future, a think-tank.

He says that introducing new schemes targeted at certain countries could, along with a returns deal with France, reduce the number of people travelling to Britain in small boats.

The new law will not stop them.

Links :

- Reuters : Explainer: How UK government plans to stop migrants arriving by boat? / UK tells small-boat migrants: we will detain and deport you

- WSJ : U.K. to Bar All Asylum Seekers Who Cross Channel on Boats

- The Guardian : What does the UK’s small boats plan mean for relations with France? / ‘Humanitarian visa’ could cut number of asylum seekers reaching UK by boat

- BBC : Plan for lifetime ban for Channel migrants is unworkable, say charities / Stopping small boats is 'priority' for British people, says Rishi Sunak

- DailyMail : Revealed: Number of migrants arriving in the UK via small boat crossings over the Channel has risen 86% compared to last year's figures

- GeoGarage blog : ‘Our boat was surrounded by dead bodies’: witnessing a migrant tragedy / ‘This is a wake-up call’: the villagers who could be Britain’s first climate refugees

Wednesday, March 8, 2023

Starlink's marine satellite system opens up new, speedy data transfer for vessel operators

While Starlink’s expanded coverage to the Bering Sea was not yet rolled

out as expected in January 2023, two Bering sea trawlers rigged up with

the system anyway to be ready when the signals become available.

Network

Innovations photo.

From National Fisherman by Paul Molyneaux

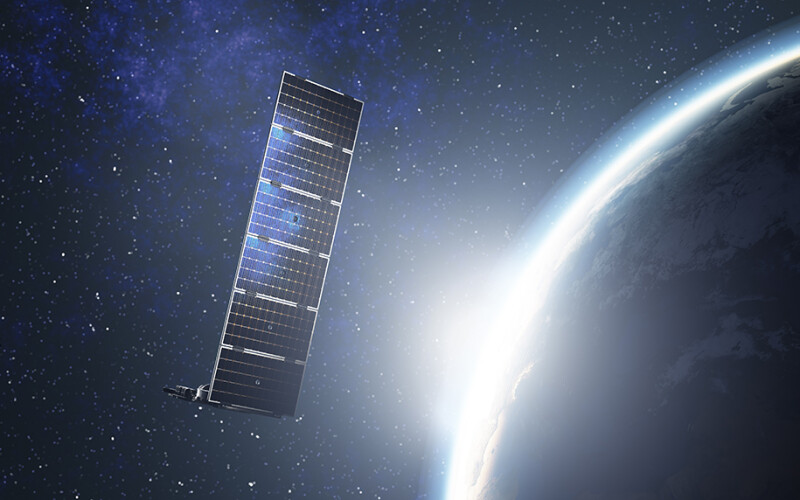

The list of satellite constellations filling earth’s outer orbits is growing at a rapid pace, and commercial fishing vessels now have many options, including low earth orbit (LEO) satellites.

Starlink, led by Elon Musk’s Space-X, utilizes the world’s largest constellation of satellites in the low Earth orbit, providing high-speed, low-latency broadband internet capable of supporting video conferencing, streaming, and more.

With Starlink, users can connect from even the most remote areas of the world with expected download speeds of 220 Mbps download and latency of 25-50ms.

Considering the amount of space junk accumulating in Earth’s outer orbital realms, the Starlink satellites can be brought back to Earth at the end of their useful lives.

With thousands of Starlink satellites in orbit and thousands more proposed, cleaning up might be prudent, but at the Pacific Marine Expo in Seattle in November 2022, the Starlink buzz focused on the speed, coverage, and price of Starlink compared to other satcom providers.

Fishermen visiting the Fusion Marine booth at the Expo expressed nothing but excitement about Starlink.

“Are you kidding me, this is better than anything out there,” said one.

“When they open up the Bering Sea, everyone’s going to have it.”

“Starlink is bringing something brand new to the market,” says Ryan Brugger, principal at Radar Marine in Bellingham, Wash.

“They have a full earth orbit constellation and are competitive on speed and price.

We’re not selling it, but it looks like a great new product.

You should talk to Fusion Marine.”

Fusion is owned by Network Innovations, which has recently become an authorized reseller of Starlink.

According to Matt George, vice president at Network Innovations (NI) Maritime, the Starlink system provides a compelling offering.

“Starlink responds to the evolving needs of some of our customers, particularly in certain areas of our maritime business.

Starlink enables us to provide the right connectivity solution for the right application at the right investment level.”

According to George, Starlink’s Flat High-Performance model is designed for high mobility applications and challenging environments, such as on the high seas.

“It can connect to more satellites, allowing for consistent connectivity at sea.

The hardware is designed for a permanent installation and is more resilient to extreme environments,” he says.

Starlink has launched 3500 Low Earth Orbit Satellites and plans 40,000 more that will enable high-speed internet service on the high seas at lower prices that are currently available.

Starlink has launched 3500 Low Earth Orbit Satellites and plans 40,000 more that will enable high-speed internet service on the high seas at lower prices that are currently available.Michael Bednarek photo.

“To date, we have primarily put Starlink’s systems on boats fishing near the coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington, including on some factory trawlers and albacore boats that are not going out beyond 200 miles,” says George.

“We have heard great feedback, although if boats have multiple wi-fi routers on board, there can be IP address conflicts.

They should do it right with a router, switch, and access points.”

While the Starlink High Performance, land-based systems can work for coastal vessels, its Flat High-Performance model offers a more appropriate offshore solution.

Several factors have enabled Starlink to deliver high-speed, low-latency service at an attractive price, dramatically changing the satellite communications playing field.

“You’d have to check the exact numbers, but they have roughly 3,500 satellites up now and are planning on over 40,000,” says George.

“We’re living in a time where it’s far less expensive to push LEO satellites into space.

Of course, it helps when you own the rockets, as SpaceX does.”

While Starlink has advertised expanding coverage in higher latitudes by January 2023, that has been delayed.

“They were supposed to open that up by the first quarter, but they’ve scaled that back and have not updated their coverage map,” says George.

“The entire land mass of Alaska is covered, though, so you’ll get something close to the coast.”

According to the Starlink website, the Marine system is now active and has been since Feb.

14, 2023.

The delay in opening up Alaska coverage did not stop fishermen from going ahead and installing the Starlink system.

“We’ve installed dual systems on a couple of factory trawlers heading up to Alaska,” says George.

“They have their existing systems and are taking the Starlink system to try it out.”

This is just the beginning, the Network Innovations’ team emphasizes, as it continues to explore the possibilities that LEO connectivity providers like Starlink provide.

“A reliable communications system definitely increases fishing safety with more options during any medical or mechanical emergency,” says George.

From weather information and sea surface temperature data from providers like Ocean Imaging (SeaView software) to going online and searching for parts to ensure they’re ready for them at their next port call, connectivity systems like Starlink create opportunities not only safety and productivity but also for crew comfort.

While vessels have rationed crew connectivity in the past, Starlink crew may be able to enjoy the same connectivity they enjoy on land, making video calls, streaming movies, and the like.

Links :

- GeoGarage blog : Want internet service on your yacht? It’ll run you $5,000 per month

- Smart Maritime Network : Starlink announces global coverage for maritime service

- Boat International : Starlink: The lowdown on Elon Musk's satellite internet system

- Cruise Critic : What Is Starlink and Which Cruise Ships Use Starlink Internet

- Naval News : Starlink Limits Ukraine’s Maritime Drones At Time Of New Russian Threat

Tuesday, March 7, 2023

A mysterious fleet is helping Russia ship oil around the world. And it’s growing

From CNN by Julia Horowitz

Russian oil is still finding its way to buyers around the world.

But even those who spend their days tracking its movement across oceans struggle to work out exactly who is ferrying it.

As Western sanctions against Russia have escalated over its invasion of Ukraine, more ships have joined an existing fleet of mysterious tankers, ready to facilitate Russia’s oil exports.

Industry insiders estimate the size of that “shadow” fleet at roughly 600 vessels, or about 10% of the global number of large tankers.

And numbers continue to climb.

Who owns and operates many of these ships remains a puzzle.

As trading Russian oil became more complex over the past year, many Western shippers withdrew their services.

New, obscure players swooped in, with shell companies in Dubai or Hong Kong involved in some cases.

Some bought boats from Europeans, while others tapped old, creaking ships that might have otherwise ended up in the scrapyard.

“You’ve gone deeper into the dark arts,” a senior executive at an oil trading firm told CNN, referring to this opaque network.

The under-the-radar fleet has increased in importance as Moscow tries to avoid working with Western shippers, and as customers in China and India supplant those in Europe, now banned from purchasing seaborne Russian oil and refined products such as diesel.

Delivery to more distant buyers requires additional boats — and ship owners willing to deal with added complexity and legal risk, especially after Group of Seven countries imposed price caps on Russian oil.

Oil pumping jacks operate in an oilfield near Russia's Neftekamsk on Nov.

19, 2020.

Andrey Rudakov/Bloomberg/Getty Images

19, 2020.

Andrey Rudakov/Bloomberg/Getty Images

The expansion of the shadow fleet highlights the dramatic changes Russia’s war has brought to the global oil market.

In its bid to keep operating, the world’s second-largest crude exporter has reshaped decades-old trading patterns and split the world’s energy system in two.

“There’s the fleet that is not doing any Russian business, and then there’s the fleet that’s almost exclusively doing Russian business,” said Richard Matthews, head of research at EA Gibson, an international shipbroker.

Only a few ships, he added, are doing a “bit of both.”

‘Gray ships’ and ‘dark ships’

As Europe has weaned itself off Russian energy, buyers in Asia have cut deals.

China boosted imports of Russian oil to 1.9 million barrels per day on average in 2022, up 19% from 2021, according to the International Energy Agency.

India ramped up purchases even more sharply, logging an 800% increase to an average of 900,000 barrels per day.

Russia’s oil exports to China and India both hit record highs in January after Europe’s ban on seaborne Russian oil took effect, according to Kpler, a data and analytics company.

Exports to Turkey, another top customer, also continued apace.

(The ban on refined oil products did not kick in until February.)

As Europe has weaned itself off Russian energy, buyers in Asia have cut deals.

China boosted imports of Russian oil to 1.9 million barrels per day on average in 2022, up 19% from 2021, according to the International Energy Agency.

India ramped up purchases even more sharply, logging an 800% increase to an average of 900,000 barrels per day.

Russia’s oil exports to China and India both hit record highs in January after Europe’s ban on seaborne Russian oil took effect, according to Kpler, a data and analytics company.

Exports to Turkey, another top customer, also continued apace.

(The ban on refined oil products did not kick in until February.)

Filling these orders requires boats amenable to the trip.

Russia’s national fleet doesn’t have enough vessels.

That’s where the “shadow fleet” comes in.

Matthew Wright, senior freight analyst at Kpler, sorts the boats moving Russian crude into two categories: “gray ships” and “dark ships.” Gray ships have been sold since the invasion — mostly by owners in Europe to firms in the Middle East and Asia that weren’t previously active in the tanker market.

Dark ships, on the other hand, are veterans of campaigns by Iran and Venezuela to avoid Western sanctions that have recently switched to carrying Russian crude.

We read all day so you don’t have to.

Get our nightly newsletter for all the top business stories you need to know.

“There is often some evidence that they have been disguising their activities by turning off their AIS transponder,” Wright said of the “dark” ships, referring to technology that helps identify and locate vessels.

While Western countries have banned most Russian oil imports, there aren’t any rules preventing Western ships from delivering to buyers such as China and India, or from providing services such as insurance — so long as the G7 price caps are respected.

Ships with European owners accounted for 36% of Russian crude trade in January, according to Kpler.

But the legal and reputational risks of failing to comply with the price caps loom large.

At the same time, Russia is eager to stop working with Western shippers.

That has led to the development of a new cohort, whose makeup is murkier — and history more checkered.

“The dark fleet that has been around carrying Venezuelan and Iranian oil globally is something we all expected to grow, and it has,” said Janiv Shah, senior analyst at Rystad Energy, a consultancy.

One reason: Sending Russian oil on longer trips to China or India is less efficient than shipping it to nearby countries such as Finland.

Russia now needs four times as much shipping capacity for its crude as it did before the invasion, according to EA Gibson.

As a result, an estimated 25 to 35 vessels are being sold per month into the shadow fleet, according to anothersenior executive at an oil trading firm.

Global Witness, a nonprofit, estimates that a quarter of oil tanker sales between late February 2022 and January this year involved unknown buyers, roughly double the proportion the previous year.

Demand could increase in the coming months if China needs more fuel to power its economic recovery.

Russia’s national fleet doesn’t have enough vessels.

That’s where the “shadow fleet” comes in.

Matthew Wright, senior freight analyst at Kpler, sorts the boats moving Russian crude into two categories: “gray ships” and “dark ships.” Gray ships have been sold since the invasion — mostly by owners in Europe to firms in the Middle East and Asia that weren’t previously active in the tanker market.

Dark ships, on the other hand, are veterans of campaigns by Iran and Venezuela to avoid Western sanctions that have recently switched to carrying Russian crude.

We read all day so you don’t have to.

Get our nightly newsletter for all the top business stories you need to know.

“There is often some evidence that they have been disguising their activities by turning off their AIS transponder,” Wright said of the “dark” ships, referring to technology that helps identify and locate vessels.

While Western countries have banned most Russian oil imports, there aren’t any rules preventing Western ships from delivering to buyers such as China and India, or from providing services such as insurance — so long as the G7 price caps are respected.

Ships with European owners accounted for 36% of Russian crude trade in January, according to Kpler.

But the legal and reputational risks of failing to comply with the price caps loom large.

At the same time, Russia is eager to stop working with Western shippers.

That has led to the development of a new cohort, whose makeup is murkier — and history more checkered.

“The dark fleet that has been around carrying Venezuelan and Iranian oil globally is something we all expected to grow, and it has,” said Janiv Shah, senior analyst at Rystad Energy, a consultancy.

One reason: Sending Russian oil on longer trips to China or India is less efficient than shipping it to nearby countries such as Finland.

Russia now needs four times as much shipping capacity for its crude as it did before the invasion, according to EA Gibson.

As a result, an estimated 25 to 35 vessels are being sold per month into the shadow fleet, according to anothersenior executive at an oil trading firm.

Global Witness, a nonprofit, estimates that a quarter of oil tanker sales between late February 2022 and January this year involved unknown buyers, roughly double the proportion the previous year.

Demand could increase in the coming months if China needs more fuel to power its economic recovery.

Oil tankers are seen at the Sheskharis complex, part of Chernomortransneft JSC, a subsidiary of Transneft PJSC, in Novorossiysk, Russia, on Oct. 11.

This is one of the largest facilities for oil and petroleum products in southern Russia. / AP

Questions and risks

If a greater percentage of the global fleet is being used for Russian crude and petroleum products, that eats up capacity, raising costs for all oil traders.

“There’s been a massive increase in inefficiencies in the way the tanker market operates,” said Wright of Kpler.

There are also questions about who ultimately runs the shadow fleet.

Some suspect a portion of the shell companies that have cropped up have ties to “the Russian state or certain politically connected players,” according to Sergey Vakulenko, a former executive at a Russian oil company, now nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

The EU said the Dubai-based firm, registered a decade ago, had been “operating as one of the key companies managing and operating the maritime transport of Russian oil,” and that the “Russian Federation is the ultimate beneficiary” of its business operations.

Moreover, experts have said the shadow fleet may be easing Russia’s ability to dodge sanctions or sell its oil above the price cap.

It’s also making it harder to discern exactly how much Russia’s barrels are selling for.

Experts including Vakulenko have found evidence in customs data that Urals, the country’s benchmark, is selling for much more at key ports than official prices indicate.

Safety is also a worry.

The dark fleet is believed to have a large contingent of vessels older than 15 years, the age at which mainstream oil companies would typically retire them due to wear and tear.

Now, more of these boats are making trips across the globe.

“You’ve got all these old vessels that are probably not being maintained to the standard they should be,” said Matthews of EA Gibson.

“The likelihood of there being a major spill or accident is growing by the day as this fleet grows.”

If a greater percentage of the global fleet is being used for Russian crude and petroleum products, that eats up capacity, raising costs for all oil traders.

“There’s been a massive increase in inefficiencies in the way the tanker market operates,” said Wright of Kpler.

There are also questions about who ultimately runs the shadow fleet.

Some suspect a portion of the shell companies that have cropped up have ties to “the Russian state or certain politically connected players,” according to Sergey Vakulenko, a former executive at a Russian oil company, now nonresident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

"The likelihood of there being a major spill or accident is growing by the day.”This past weekend, the European Union imposed sanctions on Sun Ship Management, a subsidiary of Sovcomflot, Russia’s largest shipping company.

Richard Matthews, head of research at EA Gibson

The EU said the Dubai-based firm, registered a decade ago, had been “operating as one of the key companies managing and operating the maritime transport of Russian oil,” and that the “Russian Federation is the ultimate beneficiary” of its business operations.

Moreover, experts have said the shadow fleet may be easing Russia’s ability to dodge sanctions or sell its oil above the price cap.

It’s also making it harder to discern exactly how much Russia’s barrels are selling for.

Experts including Vakulenko have found evidence in customs data that Urals, the country’s benchmark, is selling for much more at key ports than official prices indicate.

Safety is also a worry.

The dark fleet is believed to have a large contingent of vessels older than 15 years, the age at which mainstream oil companies would typically retire them due to wear and tear.

Now, more of these boats are making trips across the globe.

“You’ve got all these old vessels that are probably not being maintained to the standard they should be,” said Matthews of EA Gibson.

“The likelihood of there being a major spill or accident is growing by the day as this fleet grows.”

Links :

- WP : What We Know About the Shadow Fleet Handling Putin’s Oil

- Bloomberg : A Bay Off Southern Greece Becomes a Cog in Russia’s Oil Supply Chain

- Quartz : Russia is amassing a shadow fleet of tankers to avoid EU oil sanctions

- Splash : Splash investigation pinpoints the true scale of the shadow tanker fleet

- MSN / The Telegraph : Stopping Moscow’s oil and gas exports is the route to victory in Ukraine

- GPB : Russia has amassed a shadow fleet to ship its oil around sanctions

- Foreign Policy : How Greek Companies and Ghost Ships Are Helping Russia / Sanction-Busting Russian Ships Are Going Under the Radar

Monday, March 6, 2023

Ocean treaty: Historic agreement reached after decade of talks / ‘One of the most important talks no one has heard of’: why the high seas treaty matters

A vessel is detained for potential illegal fishing using drift nets by the US coast guard in the North Pacific Ocean.

Photograph: US Coast Guard Photo/Alamy

From The Guardian by Karne Mc Veigh

The pressure is building around critical negotiations that could, if successful, shield swathes of the world’s ocean

Almost two-thirds of the world’s ocean lies outside national boundaries.

These are the “high seas”, where fragmented and loosely enforced rules have meant a vast portion of the planet, hundreds of miles from land, is often essentially lawless.

Because of this, the high seas are more susceptible than coastal seas to exploitation.

Currently, all countries can navigate, fish (or overfish) and carry out scientific research on the high seas practically at will.

Only 1.2% of it is protected, and the increasing reach of fishing and shipping vessels, the threat of deep-sea mining, and new activities, such as “bioprospecting” of marine species, mean they are being threatened like never before.

Yet, not only does a healthy ocean provide half of the oxygen we breathe, it represents 95% of the planet’s biosphere, soaks up carbon dioxide and is Earth’s largest carbon sink.

Heavily subsidised, industrial fishers seek to exploit and profit from ocean resources that, by law, belong to everyoneJessica Battle, WWF

This week, delegates from 193 member states will begin the final talks at the UN headquarters in New York to conclude negotiations for what scientists have described as a “once in a lifetime” chance to at last protect the high seas.

Aimed at shielding huge swathes of the world’s ocean from exploitation, the talks – officially called the Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction, or BBNJ – are the fifth round of negotiations, which ended last August without agreement.

The current round of talks began last week and will end on 3 March.

The pressure is on.

Last month, the UN secretary general, António Guterres, weighed in with strong words, saying the ocean was on the “frontlines” of the war against nature, and calling on nations to stop squabbling and conclude the delayed negotiations.

Above all, the talks are critical to enforcing the 30x30 pledge from the UN biodiversity conference in December: a promise to protect 30% of the ocean (as well as 30% of the land) by 2030.

Without a high seas treaty, scientists and environmentalists agree the 30x30 pledge will fail, for the simple reason that no legal mechanism exists for establishing protected marine areas on the high seas – rendering any promises to do so meaningless.

Fishing nets onboard a seized boat in Conakry Guinea, West Africa.

Photograph: Steve Morgan/Alamy

“Every second breath being taken comes from the ocean generating oxygen,” said Liz Karan, who leads high seas protection work at the Pew Charitable Trusts.

“A healthy ocean is critical for having life on the planet – including human life.”

Karan and others are hopeful that over the next few days countries will finalise a legal framework to establish a network of high sea marine protected areas (MPAs), to create “reservoirs for adaptation and resilience” for species in a changing climate.

The deal would also set out rules for conducting environmental impact assessments for other activities (including resource exploitation) – another currently next-to-impossible task because there is no agreed way to do it.

The hold-ups in the treaty talks are practical and ideological.

When the last session wrapped in August without a deal, the conference president, Rena Lee, sounded a hopeful note: “We’re closer to the finish line than ever before.

But there are sticking points: the practical matter of how to establish and maintain MPAs in areas that aren’t governed by any individual country, and the ethical matter of how to secure fair access to marine resources for all.

“There is tension between countries that have those resources and countries that don’t,” said Karan.

“There are some countries – like big, distant-water fishing countries [nations that send fleets of fishing vessels across the globe] – that are protecting their interests.”

Even within the 51 countries – including the UK, the US and the EU – that pledged to conclude the talks by 3 March by signing up to a “high-ambition coalition” for BBNJ at the One Ocean summit in Brest, there are issues yet to be resolved.

“One of them”, Karan said, “is how this new treaty body will interact with existing organisations: in particular, the fisheries organisations.” These are bodies called RFMOs (regional fisheries management organisations) that set quotas for stocks such as tuna.

“But what the science shows”, Karan added, “is that we need to put conservation first if we are going to protect fisheries resources for future generations.”

That means immediately confronting overfishing and illegal fishing, which together are the biggest driver of environmental decline in the ocean.skip past newsletter promotion

“Heavily subsidised, industrial fishers seek to exploit and profit from ocean resources that, by law, belong to everyone,” said Jessica Battle, a senior global oceans expert for WWF who is leading the NGO’s team at the negotiations.

“It’s a tragedy of the commons.”

For Battle a legally binding high-seas treaty would be crucial to breaking down the existing silos between current management bodies, resulting in less cumulative impact and better cooperation.

There are some esoteric holdups, too, such as who owns marine genetic resources – the potential scientific discoveries in the ocean that could lead to new pharmaceutical, cosmetics, food and industrial advances.

This week, Greenpeace warned the treaty was in jeopardy as countries in the global north, including China, refused to compromise.

The latest draft of the treaty, published on Saturday, still contained major areas of disagreement, it said.

Laura Meller, an oceans campaigner at Greenpeace Nordic, said: “Negotiations must accelerate and the global north must seek compromises instead of quibbling over minor points.

China must urgently reimagine its role at these negotiations.

At Cop15, China showed global leadership but at these negotiations, it has been a difficult party.

China has an opportunity to transform global ocean governance and broker, instead of break, a landmark deal on this new Ocean Treaty.”

Among the high seas biodiversity hotspots that would benefit from being sanctuaries is the Costa Rica Dome – nutrient-rich waters that attract yellowfin tuna, migratory dolphins, endangered blue whales and leatherback sea turtles.

There is also the Emperor Seamount chain, a biodiverse series of seamounts that arches north-west of the Hawaiian islands towards Russia.

“There are corridors of the sea where whales aggregate every year.

Big undersea mountains, encrusted in corals,” said Doug McCauley, an associate professor of ocean science at the Benioff Ocean Initiative at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who contributed to a paper for the Pew Charitable Trusts highlighting 10 such proposed sanctuaries.

Getting something on paper that allows the international community to set up those parks is vital, he said.

“There’s a real opportunity to make history with this treaty,” he said.

“It is arguably one of the most important international negotiations that no one has ever heard of.”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

From BBC by Esme Stallard

Nations have reached a historic agreement to protect the world's oceans following 10 years of negotiations.

The High Seas Treaty places 30% of the seas into protected areas by 2030, aiming to safeguard and recuperate marine nature.

The agreement was reached on Saturday evening, after 38 hours of talks, at UN headquarters in New York.

The negotiations had been held up for years over disagreements on funding and fishing rights.

The last international agreement on ocean protection was signed 40 years ago in 1982 - the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

That agreement established an area called the high seas - international waters where all countries have a right to fish, ship and do research - but only 1.2% of these waters are protected.

Marine life living outside of these protected areas has been at risk from climate change, overfishing and shipping traffic.

In detail: The plan to protect the high seas

In the latest assessment of global marine species, nearly 10% were found to be at risk of extinction, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

These new protected areas, established in the treaty, will put limits on how much fishing can take place, the routes of shipping lanes and exploration activities like deep sea mining - when minerals are taken from a sea bed 200m or more below the surface.

Environmental groups have been concerned that mining processes could disturb animal breeding grounds, create noise pollution and be toxic for marine life.

The International Seabed Authority that oversees licensing told the BBC that moving forward "any future activity in the deep seabed will be subject to strict environmental regulations and oversight to ensure that they are carried out sustainably and responsibly".

Rena Lee, UN Ambassador for Oceans, brought down the gavel after two weeks of negotiations that at times threatened to unravel.

Minna Epps, director of the IUCN Ocean team, said the main issue was over the sharing of marine genetic resources.

Marine genetic resources are biological material from plants and animals in the ocean that can have benefits for society, such as pharmaceuticals, industrial processes and food.

Richer nations currently have the resources and funding to explore the deep ocean but poorer nations wanted to ensure any benefits they find are shared equally.

Dr Robert Blasiak, ocean researcher at Stockholm University, said the challenge was that no one knows how much ocean resources are worth and therefore how they could be split.

He said: "If you imagine a big, high-definition, widescreen TV, and if only like three or four of the pixels on that giant screen are working, that's our knowledge of the deep ocean. So we've recorded about 230,000 species in the ocean, but it's estimated that there are over two million."

Laura Meller, an oceans campaigner for Greenpeace Nordic, commended countries for "putting aside differences and delivering a treaty that will let us protect the oceans, build our resilience to climate change and safeguard the lives and livelihoods of billions of people"

"This is a historic day for conservation and a sign that in a divided world, protecting nature and people can triumph over geopolitics," she added.

Countries will need to meet again to formally adopt the agreement and then have plenty of work to do before the treaty can be implemented.

Liz Karan, director of Pews Trust ocean governance team, told the BBC: "It will take some time to take effect.

Countries have to ratify it [legally adopt it] for it to enter force.

Then there are a lot of institutional bodies like the Science and Technical Committee that have to get set up."

Links :

- The Guardian : Watered down: why negotiators at Cop15 are barely mentioning the ocean / Crucial high seas treaty stuck over sharing of genetic resources / High seas treaty: historic deal to protect international waters finally reached at UN

- Phys : Treaty ahoy? Talks to protect high seas near finish line

- The Nature Conservancy : High Time for a High Seas Treaty

- Oceanographic : UN High Seas Treaty: New negotiations begin in New York

- UN : UN delegates reach historic agreement on protecting marine biodiversity in international waters

Sunday, March 5, 2023

Australia's Great Barrier Reef will survive if warming kept to 1.5 degrees, study finds

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority has confirmed an unprecedented sixth mass coral bleaching event since 1998.

From CNN by Reyters

A study released on Friday by an Australian university looking at multiple catastrophes hitting the Great Barrier Reef has found for the first time that only 2% of its area has escaped bleaching since 1998, then the world's hottest year on record.

If global warming is kept to 1.5 degrees, the maximum rise in average global temperature that was the focus of the COP26 United Nations climate conference, the mix of corals on the Barrier Reef will change but it could still thrive, said the study's lead author Professor Terry Hughes, of the Australian Research Council's Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies.

"If we can hold global warming to 1.5 degrees global average warming then I think we'll still have a vibrant Great Barrier Reef," he said.

Bleaching is a stress response by overheated corals during heat waves, where they lose their color and many struggle to survive.

Eighty percent of the World Heritage-listed wonder has been bleached severely at least once since 2016, the study by James Cook University in Australia's Queensland state found.

Great Barrier Reef, north-east of Port Douglas, Queensland, Australia.

The study found the corals adapted to have a higher heat threshold if they had survived a previous bleaching event, but the gap between bleaching events has shrunk, giving the reefs less time to recover between each episode.

Australia, which last week said it would not back a pledge led by the United States and the European Union to cut methane emissions, needs to do more to cut greenhouse gas emissions, Hughes said.

"The government is still issuing permits for new coal mines and for new methane gas deals and it's simply irresponsible in terms of Australia's responsibilities to the Great Barrier Reef," he said.

The Great Barrier Reef is comprised of more than 3,000 individual reefs stretching for 2,300km (1,429 miles). The ecosystem supports 65,000 jobs in reef tourism. Globally, hundreds of millions of people depend on the survival of coral reefs for their livelihoods and food security.

"If we go to 3, 4 degrees of global average warming which is tragically the trajectory we are currently on, then there won't be much left of the Great Barrier Reef or any other coral reefs throughout the tropics," Hughes told Reuters.

The Great Barrier Reef is comprised of more than 3,000 individual reefs stretching for 2,300km (1,429 miles). The ecosystem supports 65,000 jobs in reef tourism. Globally, hundreds of millions of people depend on the survival of coral reefs for their livelihoods and food security.

"If we go to 3, 4 degrees of global average warming which is tragically the trajectory we are currently on, then there won't be much left of the Great Barrier Reef or any other coral reefs throughout the tropics," Hughes told Reuters.

Links :