Saturday, April 10, 2021

Friday, April 9, 2021

Satellite images show huge Russian military buildup in the Arctic

From CNN by Nick Paton Walsh

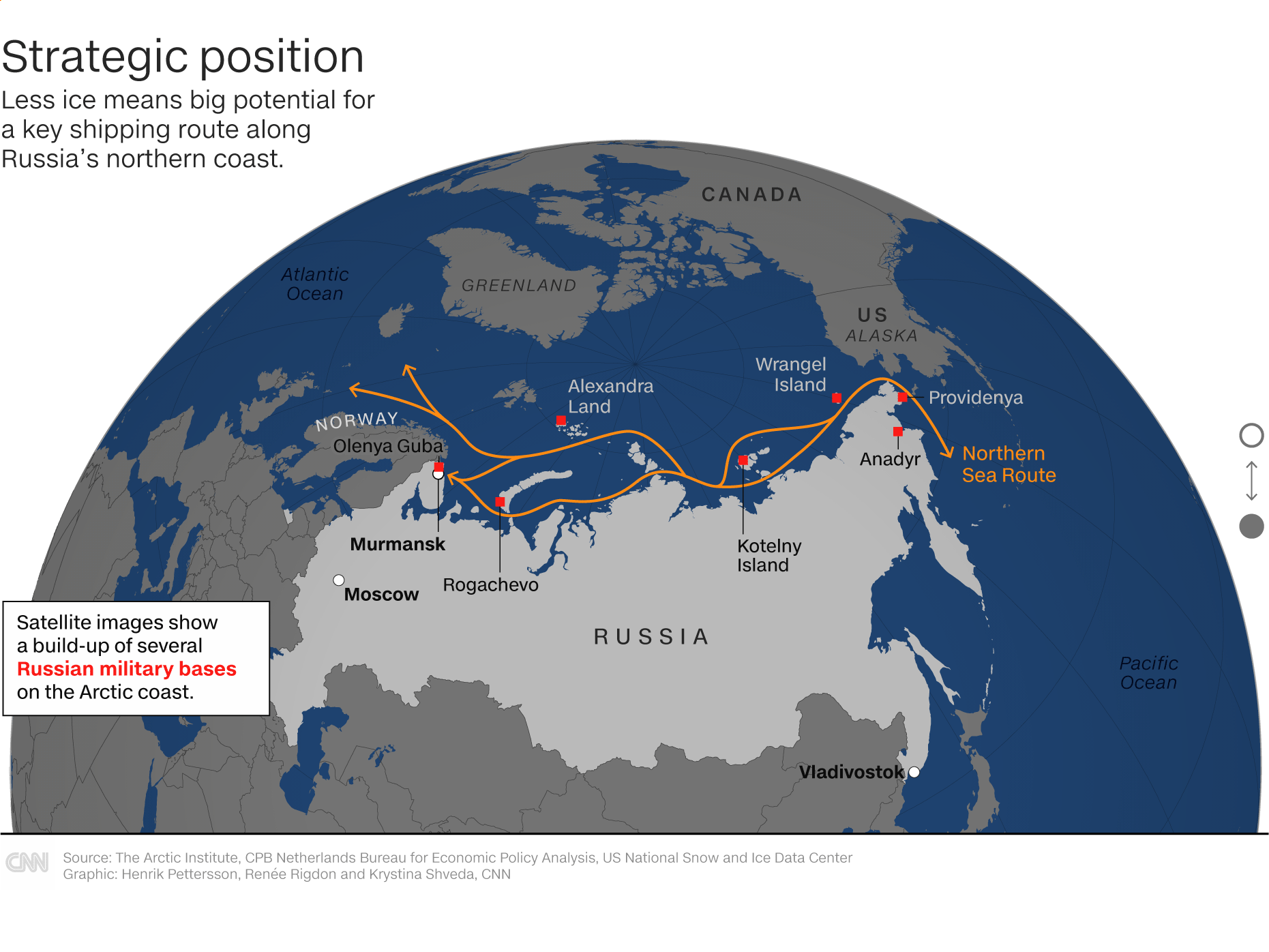

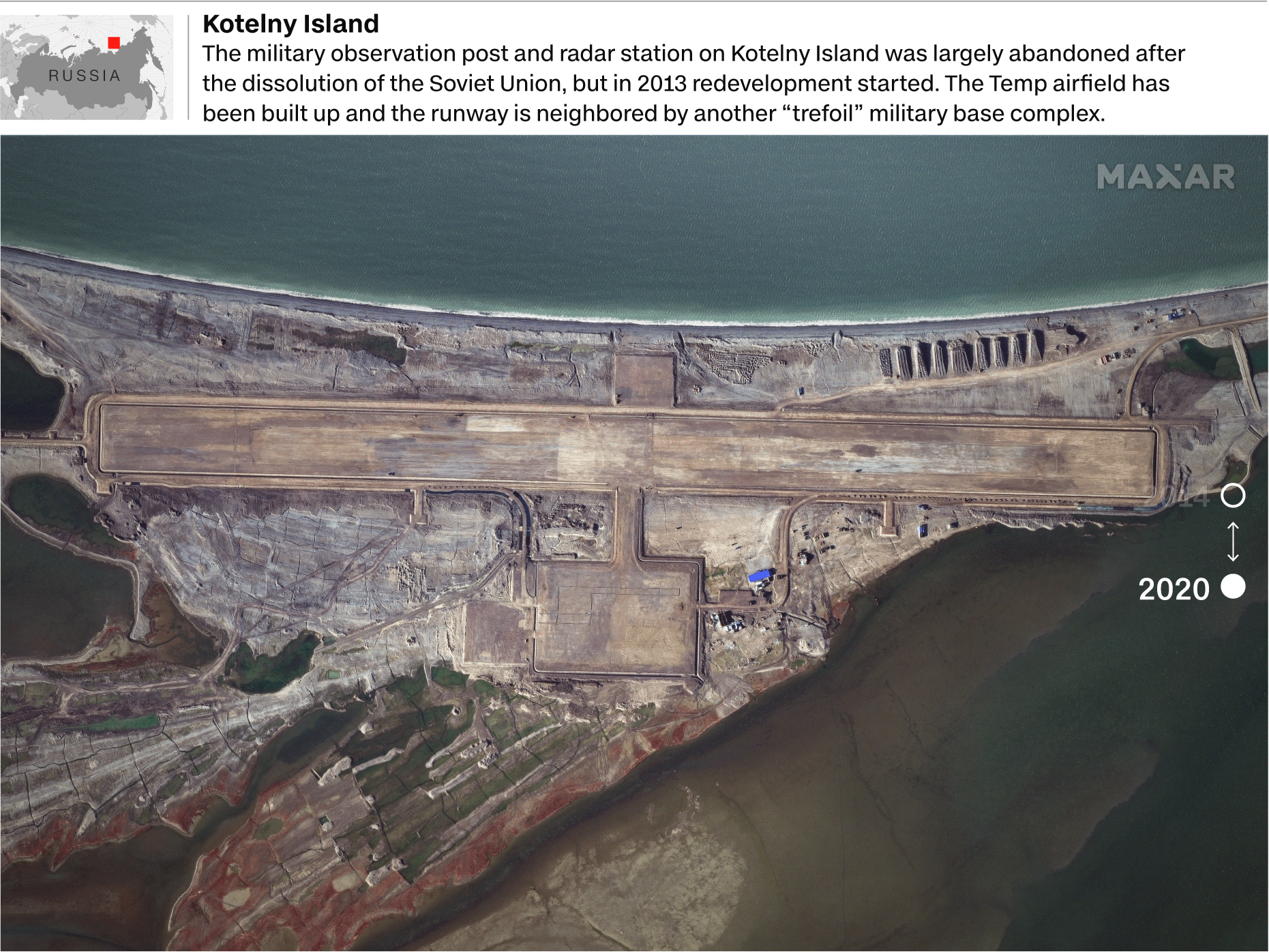

Russia is amassing unprecedented military might in the Arctic and testing its newest weapons in a region freshly ice-free due to the climate emergency, in a bid to secure its northern coast and open up a key shipping route from Asia to Europe.

Weapons experts and Western officials have expressed particular concern about one Russian 'super-weapon,' the Poseidon 2M39 torpedo.

Development of the torpedo is moving fast with Russian President Vladimir Putin requesting an update on a "key stage" of the tests in February from his defense minister Sergei Shoigu, with further tests planned this year, according to multiple reports in state media.

Images show build up of Russia's military presence in the Arctic 04:15

This unmanned stealth torpedo is powered by a nuclear reactor and intended by Russian designers to sneak past coastal defenses -- like those of the US -- on the sea floor.

The device is intended to deliver a warhead of multiple megatons, according to Russian officials, causing radioactive waves that would render swathes of the target coastline uninhabitable for decades.

In November, Christopher A Ford, then assistant secretary of state for International Security and Non-Proliferation, said the Poseidon is designed to "inundate U.S.coastal cities with radioactive tsunamis."

The device is intended to deliver a warhead of multiple megatons, according to Russian officials, causing radioactive waves that would render swathes of the target coastline uninhabitable for decades.

In November, Christopher A Ford, then assistant secretary of state for International Security and Non-Proliferation, said the Poseidon is designed to "inundate U.S.coastal cities with radioactive tsunamis."

An "onyx" anti-ship cruise missile launched by the Northern Fleet in Alexandra Land, near an Arctic "trefoil" base.

Credit: Russian Ministry of Defense

Credit: Russian Ministry of Defense

Experts agree that the weapon is "very real" and already coming to fruition.

The head of Norwegian intelligence, Vice Admiral Nils Andreas Stensønes, told CNN that his agency has assessed the Poseidon as "part of the new type of nuclear deterrent weapons.

And it is in a testing phase.

But it's a strategic system and it's aimed at targets ...

and has an influence far beyond the region in which they test it currently." Stensønes declined to give details on the torpedo's testing progress so far.

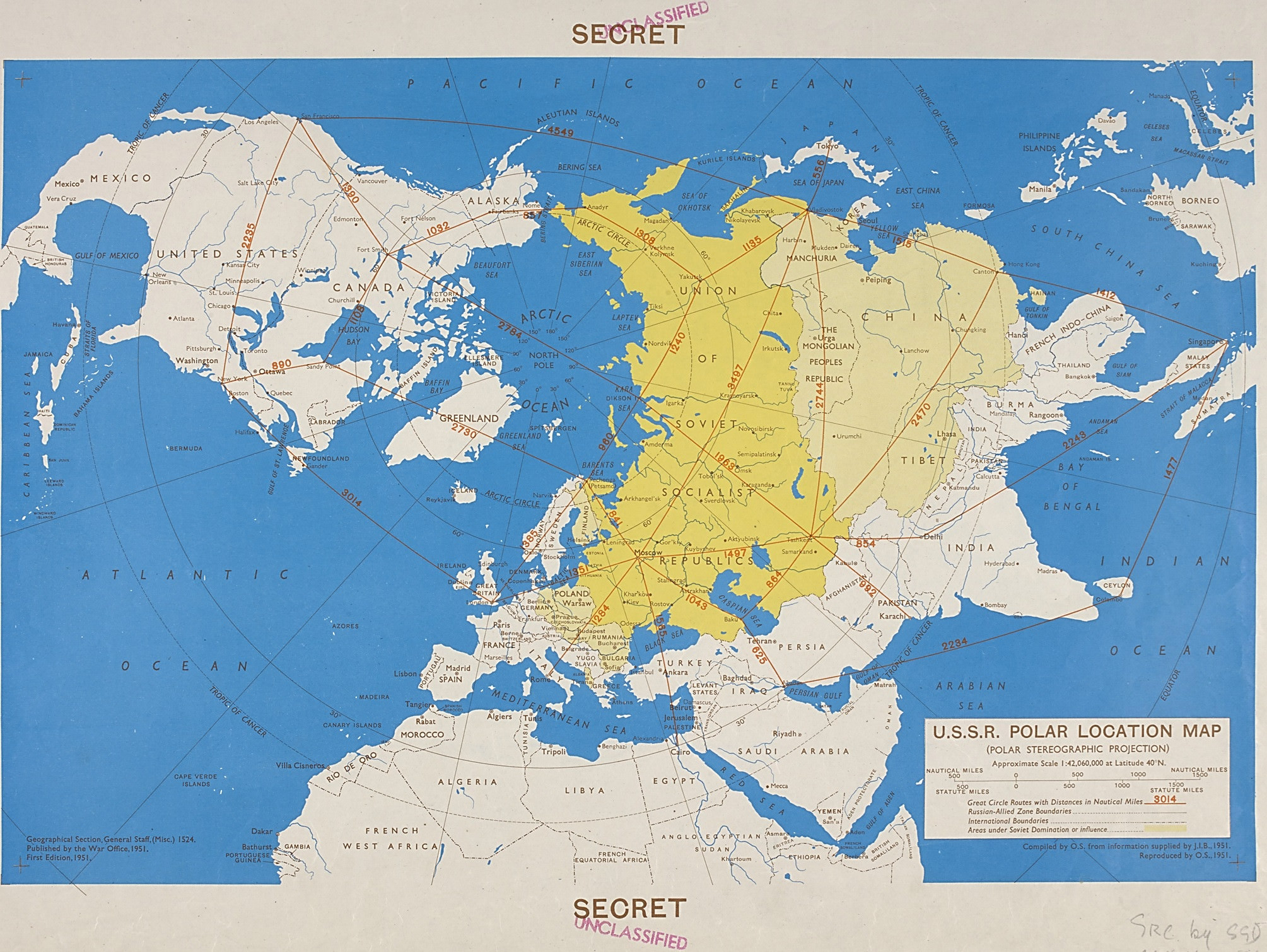

USSR polar location map, 1951

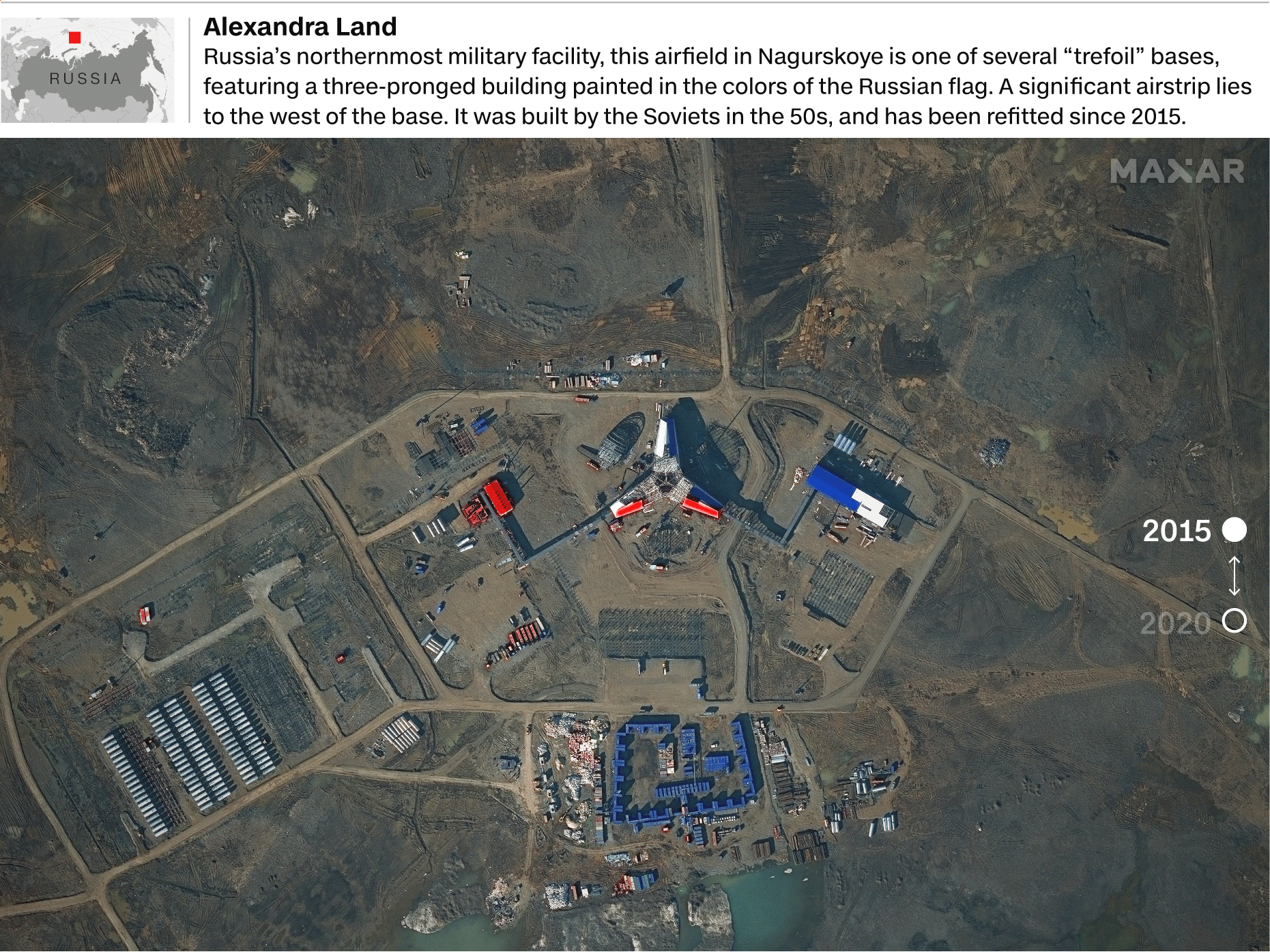

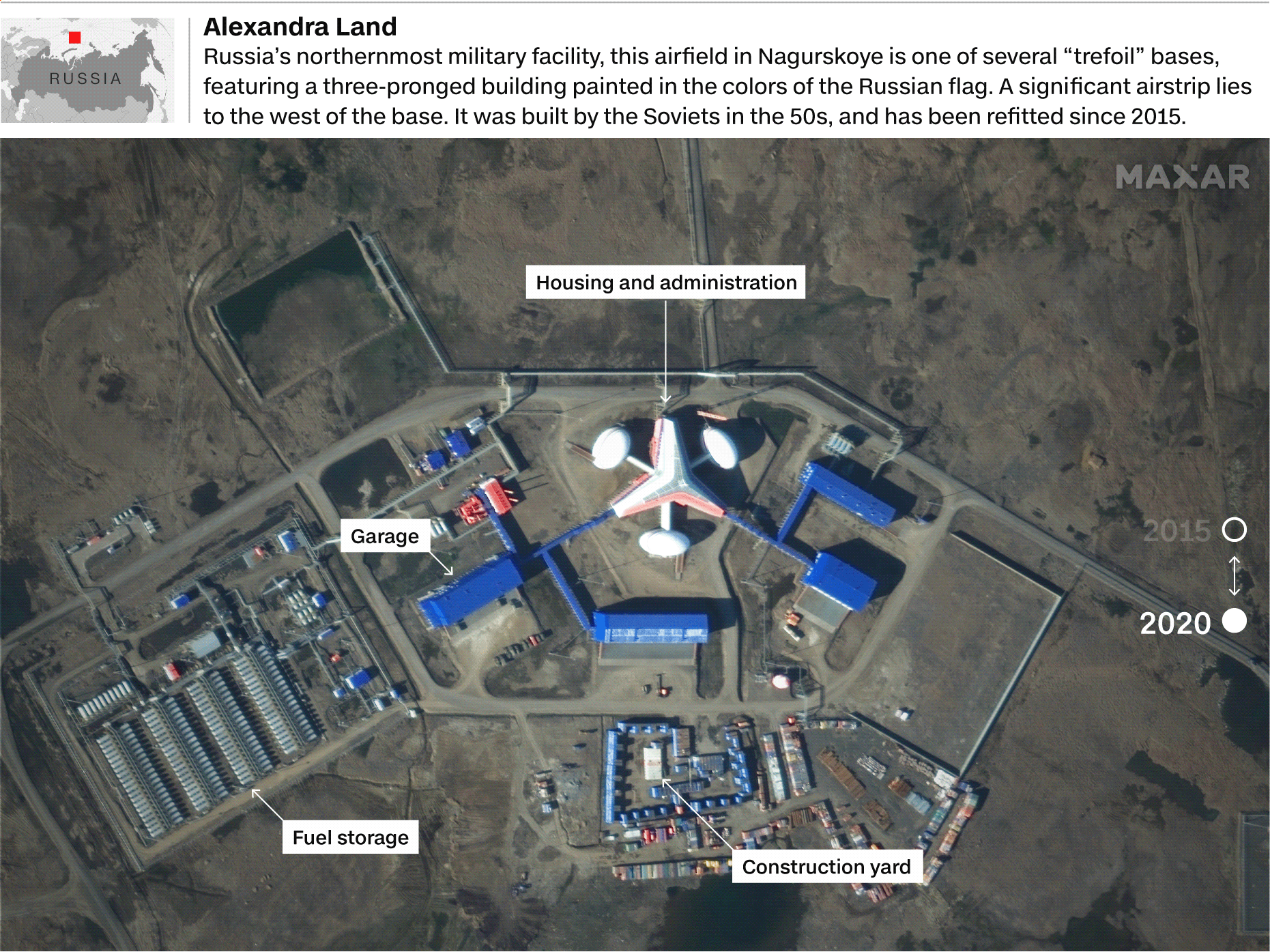

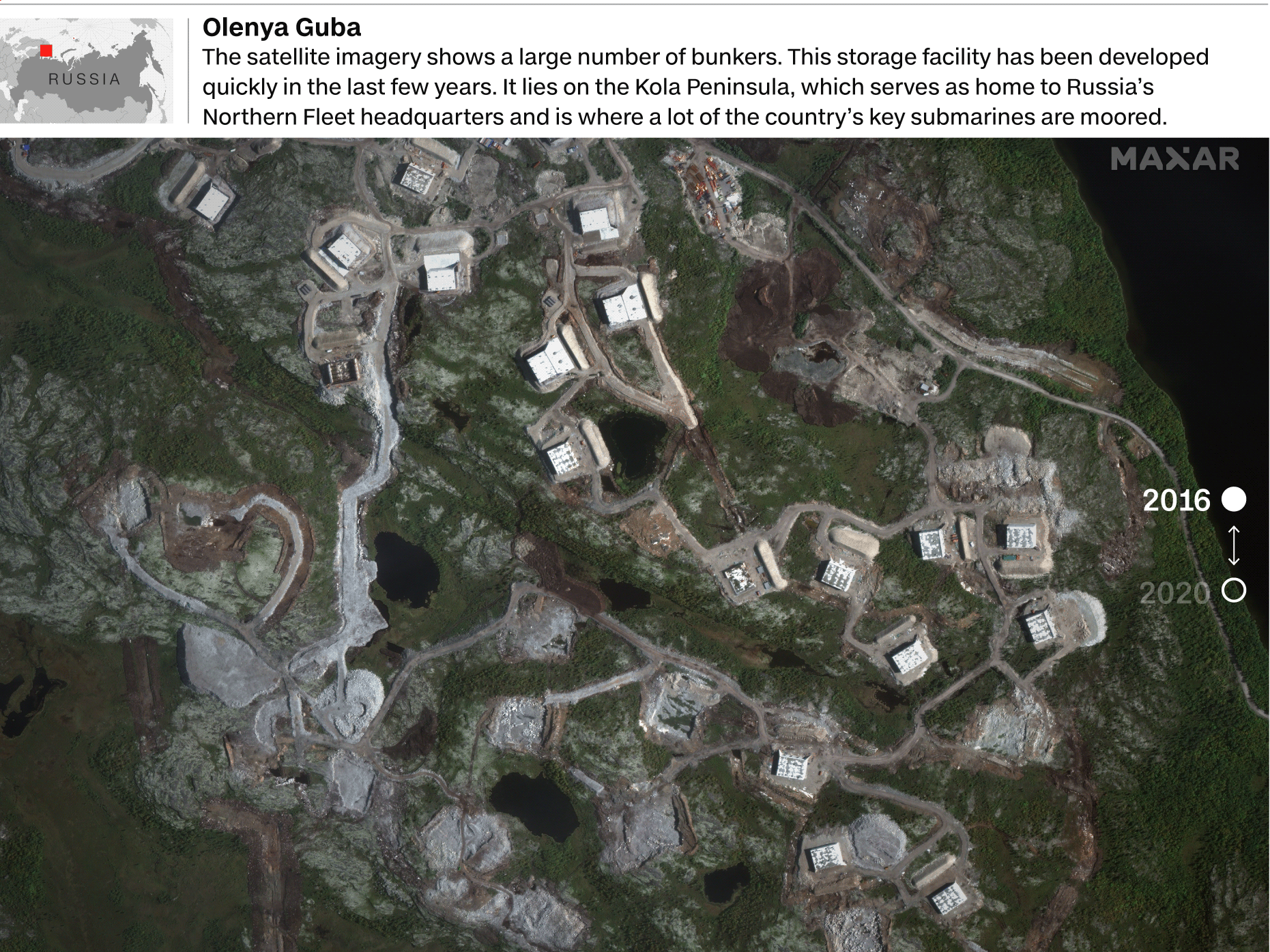

Satellite images provided to CNN by space technology company Maxar detail a stark and continuous build-up of Russian military bases and hardware on the country's Arctic coastline, together with underground storage facilities likely for the Poseidon and other new high-tech weapons.

The Russian hardware in the High North area includes bombers and MiG31BM jets, and new radar systems close to the coast of Alaska.

The Russian build-up has been matched by NATO and US troop and equipment movements.

American B-1 Lancer bombers stationed in Norway's Ørland air base have recently completed missions in the eastern Barents Sea, for example.

The US military's stealth Seawolf submarine was acknowledged by US officials in August as being in the area.

A senior State Department official told CNN: "There's clearly a military challenge from the Russians in the Arctic," including their refitting of old Cold War bases and build-up of new facilities on the Kola Peninsula near the city of Murmansk.

"That has implications for the United States and its allies, not least because it creates the capacity to project power up to the North Atlantic," the official said.

Correction: A previous version of this graphic displayed an image from 2016 instead of 2020.

This has been fixed.

Source: Satellite image ©2021 Maxar Technologies, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

Graphic: Henrik Pettersson, CNN

Graphic: Henrik Pettersson, CNN

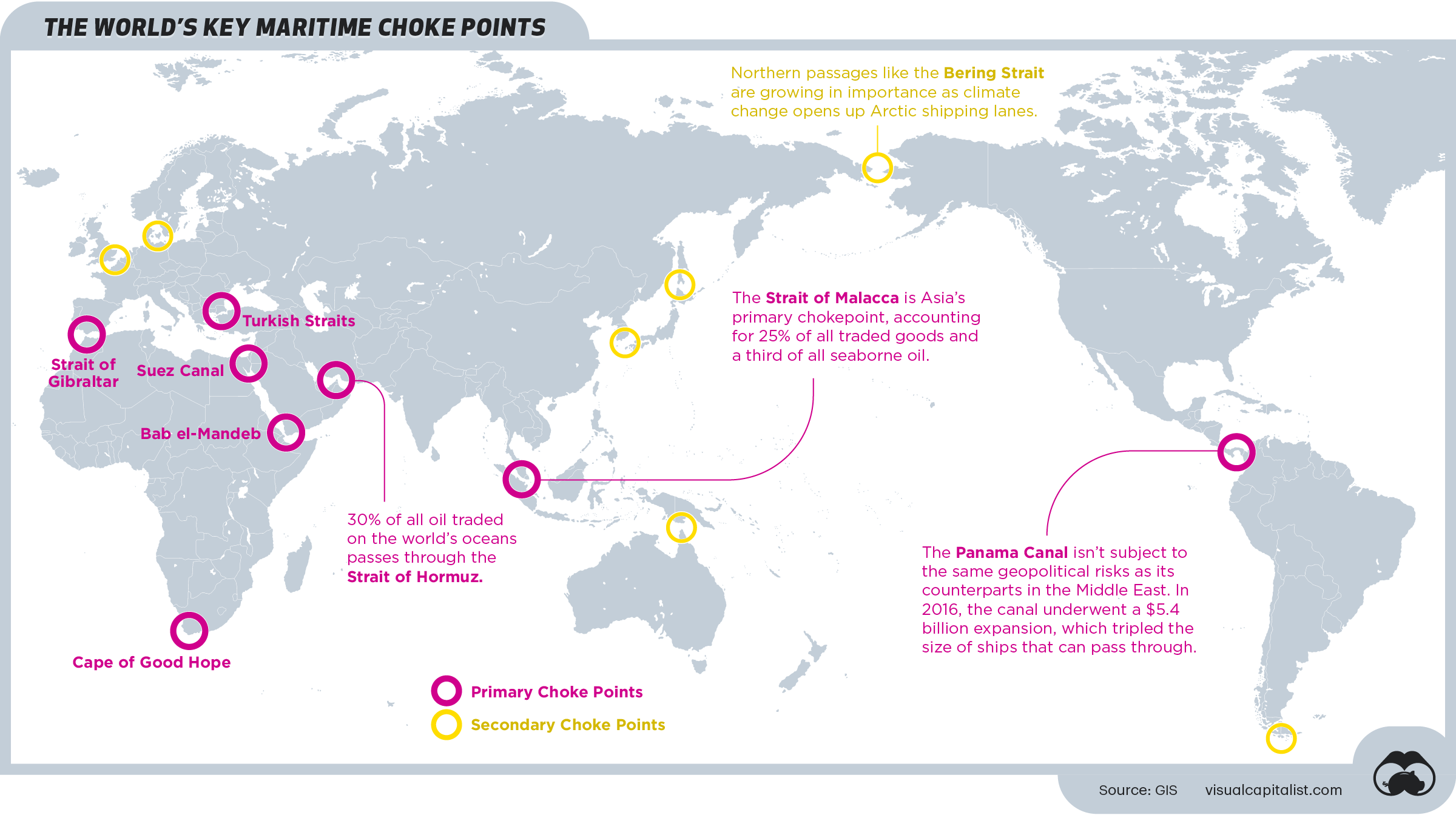

The satellite images show the slow and methodical strengthening of airfields and "trefoil" bases -- with a shamrock-like design, daubed in the red, white and blue of the Russian flag -- at several locations along Russia's Arctic coast over the past five years.

The bases are inside Russian territory and part of a legitimate defense of its borders and coastline.

US officials have voiced concern, however, that the forces might be used to establish de facto control over areas of the Arctic that are further afield, and soon to be ice-free.

"Russia is refurbishing Soviet-era airfields and radar installations, constructing new ports and search-and-rescue centers, and building up its fleet of nuclear- and conventionally-powered icebreakers," Lt.

Col. Thomas Campbell, a Pentagon spokesman, told CNN.

The 50 Let Pobedy (50 years of victory) icebreaker moving through the Arctic ice, said to be in January this year, in a first transit of the eastern seas in deep winter.

Credit: Rosatom State Nuclear Energy Corporation

Credit: Rosatom State Nuclear Energy Corporation

"It is also expanding its network of air and coastal defense missile systems, thus strengthening its anti-access and area-denial capabilities over key portions of the Arctic," he added.

Campbell also noted the recent creation of a Quick Reaction Alert force at two Arctic airfields -- Rogachevo and Anadyr -- and the trial of one at Nagurskoye airfield last year.

Satellite imagery from March 16 shows probable MiG31BMs at Nagurskoye for what is thought to be the first time, bringing a new capability of Russian stealth air power to the far north.

High-tech weapons are also being regularly tested in the Arctic area, according to Russian officials quoted in state media and Western officials.

Campbell added that in November, Russia claimed the successful test of the 'Tsirkon' anti-ship hypersonic cruise missile.

Campbell also noted the recent creation of a Quick Reaction Alert force at two Arctic airfields -- Rogachevo and Anadyr -- and the trial of one at Nagurskoye airfield last year.

Satellite imagery from March 16 shows probable MiG31BMs at Nagurskoye for what is thought to be the first time, bringing a new capability of Russian stealth air power to the far north.

High-tech weapons are also being regularly tested in the Arctic area, according to Russian officials quoted in state media and Western officials.

Campbell added that in November, Russia claimed the successful test of the 'Tsirkon' anti-ship hypersonic cruise missile.

The Tsirkon and the Poseidon are part of a new generation of weapons pledged by Putin in 2018 as strategic game changers in a fast-changing world.

At the time US officials scorned the new weapons as technically far-fetched and improbable, yet they appear to be nearing fruition.

The Norwegian intelligence chief Stensønes told CNN the Tsirkon as a "new technology, with hypersonic speeds, which makes it hard to defend against."

On Thursday, Russian state news agency TASS cited a source in the military industrial complex as saying there had been another successful test of the Tsirkon from the Admiral Gorshkov warship, saying all four test rockets had hit their target, and that another more advanced level of tests would begin in May or June.

The climate emergency has removed many of Russia's natural defenses to its north, such as walls of sheet ice, at an unanticipated rate.

"The melt is moving faster than scientists predicted or thought possible several years ago," said the senior State Department official.

"It's going to be a dramatic transformation in the decades ahead in terms of physical access."

Source: Satellite image ©2021 Maxar Technologies, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

Graphic: Henrik Pettersson, CNN

Graphic: Henrik Pettersson, CNN

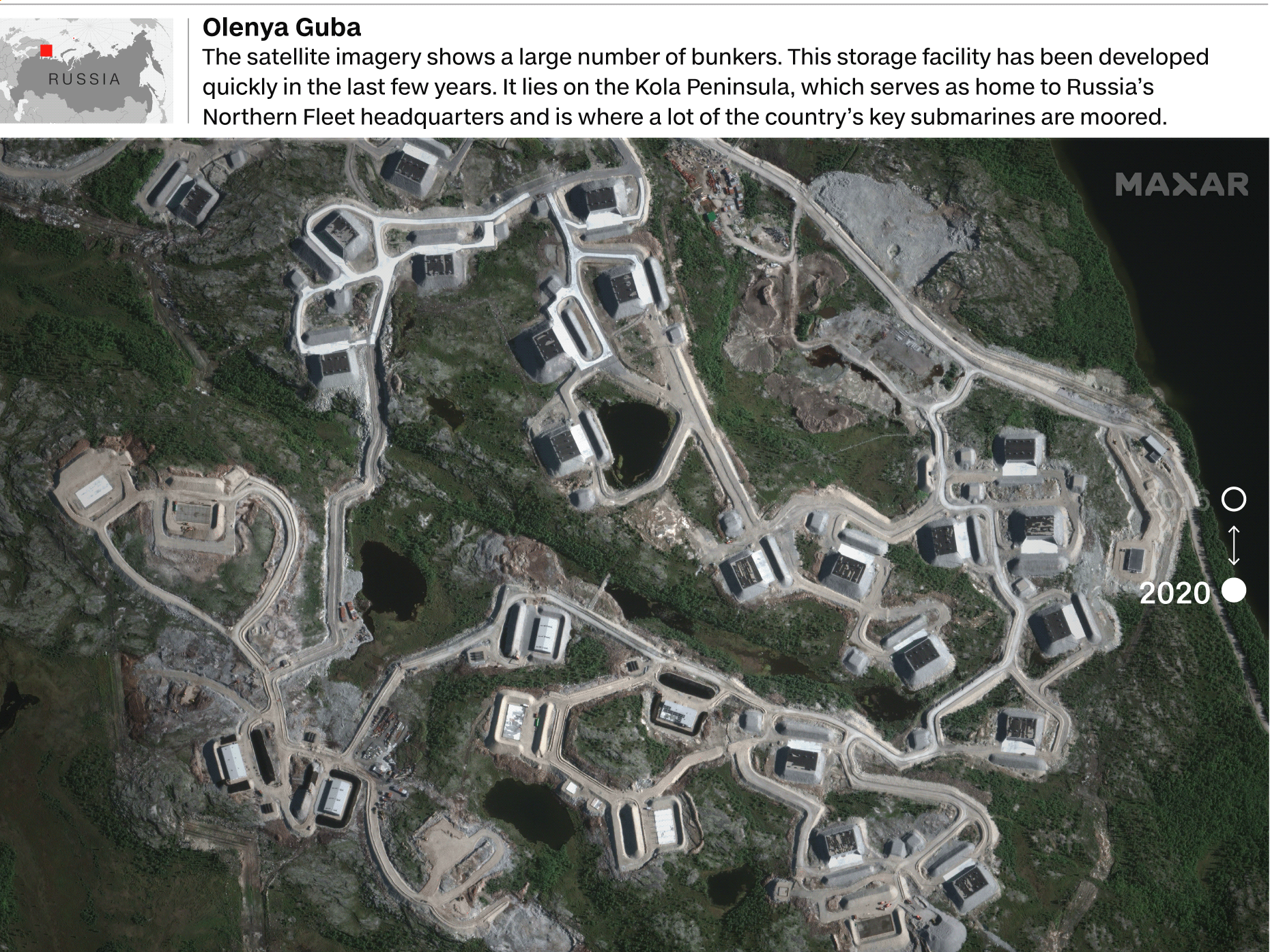

US officials also expressed concern at Moscow's apparent bid to influence the "Northern Sea Route" -- a shipping lane that runs from between Norway and Alaska, along Russia's northern coast, across to the North Atlantic.

The 'NSR' potentially halves the time it currently takes shipping containers to reach Europe from Asia via the Suez Canal.

Russia's Rosatom state nuclear company released elaborately produced drone video this February of the 'Christophe de Margerie' tanker completing an eastern route across the Arctic in winter for the first time, accompanied by the '50 Let Pobedy' nuclear icebreaker for its journey in three of the six Arctic seas.

Campbell said Russia sought to exploit the NSR as a "major international shipping lane," yet voiced concern at the rules Moscow was seeking to impose on vessels using the route.

"Russian laws governing NSR transits exceed Russia's authority under international law," the Pentagon spokesman said.

"They require any vessel transiting the NSR through international waters to have a Russian pilot onboard to guide the vessel.

Russia is also attempting to require foreign vessels to obtain permission before entering the NSR."

The senior State Department official added: "The Russian assertions about the Northern Sea Route is most certainly an effort to lay down some rules of the road, get some de facto acquiescence on the part of the international community, and then claim this is the way things are supposed to work."

Elizabeth Buchanan, lecturer of Strategic Studies at Deakin University, Australia, said that "basic geography affords Russia the NSR which is increasingly seeing thinner ice for more of the year making it commercially viable to use as a transport artery.

This might yet transform global shipping, and with it the movements of 90+% of all goods globally."

The State Department official believes the Russians are mostly interested in exporting hydrocarbons -- essential to the country's economy -- along the route, but also in the resources being uncovered by the fast melt.

The flexing of their military muscles in the north -- key to Moscow's nuclear defense strategy, and also mostly on Russian coastal territory -- could be a bid to impose their writ on the wider area, the official said.

"When the Russians are testing weapons, jamming GPS signals, closing off airspace or sea space for exercises, or flying bombers over the Arctic along the airspace of allies and partners, they are always trying to send a message," the official added.

Russia insists motives are peaceful and economic

This might yet transform global shipping, and with it the movements of 90+% of all goods globally."

The State Department official believes the Russians are mostly interested in exporting hydrocarbons -- essential to the country's economy -- along the route, but also in the resources being uncovered by the fast melt.

The flexing of their military muscles in the north -- key to Moscow's nuclear defense strategy, and also mostly on Russian coastal territory -- could be a bid to impose their writ on the wider area, the official said.

"When the Russians are testing weapons, jamming GPS signals, closing off airspace or sea space for exercises, or flying bombers over the Arctic along the airspace of allies and partners, they are always trying to send a message," the official added.

Russia insists motives are peaceful and economic

Russia's foreign ministry declined to comment, yet Moscow has long maintained its goals in the Arctic are economic and peaceful.

A March 2020 document by Kremlin policymakers presented Russia's key goals in an area behind 20% of its exports and 10% of its GDP.

The strategy focuses on ensuring Russia's territorial integrity and regional peace.

It also expresses the need to guarantee high living standards and economic growth in the region, as well as developing a resource base and the NSR as "a globally competitive national transport corridor."

Putin regularly extols the importance of Russia's technological superiority in the Arctic.

In November, during the unveiling of a new icebreaker in St. Petersburg, the Russian President said: "It is well-known that we have a unique icebreaker fleet that holds a leading position in the development and study of Arctic territories.

We must reaffirm this superiority constantly, every day."

Putin said of a submarine exercise last week in which three submarines surfaced at the same time in the polar ice: "The Arctic expedition ... has no analogues in the Soviet and the modern history of Russia."

Among these new weapons is the Poseidon 2M39.

The plans for this torpedo were initially revealed in an apparently purposeful brandishing of a document discussing its capabilities by a Russian general in 2015.

It was subsequently partially dismissed by analysts as a 'paper tiger' weapon, meant to terrify with its apocalyptic destructive powers that appear to slip around current treaty requirements, but not to be successfully deployed.

A Russian Delta IV submarine photographed on top of ice near Alexandra Island on March 27, during an exercise, with a likely hole blown in the ice to its left from underwater demolition.

Yet a series of developments in the Arctic -- including, according to Russian media reports, the testing of up to three Russian submarines designed to carry the stealth weapon, which has been suggested to be 20 meters long -- have now led analysts to consider the project real and active.

Russia's state news agency, RIA Novosti, cited a "source" on Monday saying that tests for the Belgorod submarine, especially developed to be armed with the Poseidon torpedo, would be completed in September.

Manash Pratim Boruah, a submarine expert at Jane's Fighting Ships, said: "The reality of the weapon is clear.

You can absolutely see development around the torpedo, which is happening.

There is a very good probability that the Poseidon will be tested, and then there is a danger of it polluting a lot.

Even without a warhead, but definitely with just a nuclear reactor inside."

Boruah said some of the specifications for the torpedo leaked by the Russians were optimistic and doubted it could reach a speed of 100 knots (around 115 miles per hour) with a 100MW nuclear reactor.

He added that at such a speed, it would probably be detected quite easily as it would create a large acoustic signature.

"Even if you tone it down from the speculation, it is still quite dangerous," he said.

Source: Satellite image ©2021 Maxar Technologies, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

Graphic: Henrik Pettersson, CNN

Boruah added that the construction of storage bays for the Poseidon, probably around Olenya Guba on the Kola Peninsula, were meant to be complete next year.

He also expressed concerns about the Tsirkon hyper-sonic missile that Russia says it has tested twice already, which at speeds of 6 to 7 Mach would "definitely cause a lot of damage without a particularly having big warhead itself."

Katarzyna Zysk, professor of international relations at the state-run Norwegian Institute for Defence Studies, said the Poseidon was "getting quite real," given the level of infrastructure development and testing of submarines to carry the torpedo.

"It is absolutely a project that will be used to scare, as a negotiation card in the future, perhaps in arms control talks," Zysk said.

"But in order to do so, it has to be credible.

This seems to be real."

Stensønes also raised the concern that testing such nuclear weapons could have serious environmental consequences.

"We are ecologically worried.

This is not only a theoretical thing: in fact, we have seen serious accidents in the last few years," he said, referring to the testing of the Burevestnik missile which was reported to have caused a fatal nuclear accident in 2019.

"The potential of a nuclear contamination is absolutely there."

Links :

Thursday, April 8, 2021

USS Johnston: Sub dives to deepest-known shipwreck

World’s deepest-known shipwreck finally seen.

From BBC by Rebecca Morelle

The USS Johnston has been relocated, surveyed and filmed at a depth of 6,456m in the Philippine Sea

A submersible has dived to the world’s deepest-known shipwreck.

The vessel reached the USS Johnston, which lies 6.5km (4 miles) beneath the waves in the Philippine Sea in the Pacific Ocean.

Explorers spent several hours surveying and filming the wreck over a series of dives.

The 115m-long US Navy destroyer sank during the Battle off Samar in 1944 after a fierce battle with a large fleet of Japanese warships.

Victor Vescovo, who led the expedition and piloted the sub, said: “The wreck is so deep so there's very little oxygen down there, and while there is a little bit of contamination from marine life, it's remarkably well intact except for the damage it took from the furious fight.”

The USS Johnston has been relocated, surveyed and filmed at a depth of 6,456m in the Philippine Sea

A submersible has dived to the world’s deepest-known shipwreck.

The vessel reached the USS Johnston, which lies 6.5km (4 miles) beneath the waves in the Philippine Sea in the Pacific Ocean.

Explorers spent several hours surveying and filming the wreck over a series of dives.

The 115m-long US Navy destroyer sank during the Battle off Samar in 1944 after a fierce battle with a large fleet of Japanese warships.

Victor Vescovo, who led the expedition and piloted the sub, said: “The wreck is so deep so there's very little oxygen down there, and while there is a little bit of contamination from marine life, it's remarkably well intact except for the damage it took from the furious fight.”

The destroyer was in good condition apart from the damage it sustained from the battle

The remains of the USS Johnston were first discovered in 2019, and parts of the destroyer were filmed with a remotely operated vehicle (ROV).

But a large part of the wreckage lay deeper than the ROV was able to reach, so for this expedition a submersible called the DSV Limiting Factor was deployed.

Only 141 of the USS Johnston's 327 crew survived the battle

Only 141 of the USS Johnston's 327 crew survived the battleThe vessel has a 9cm-thick (3.5in) titanium pressure hull that two people can fit inside, and it is able to descend to any depth.

Previously it has explored the deepest place in the ocean, the Mariana Trench, which lies almost 11km down, as well as the Titanic.

It took several dives to relocate the wreck of the USS Johnston, but then Victor Vescovo, along with engineer Shane Eigler on one dive and naval historian Parks Stephenson on another, were able to spend time surveying and filming the destroyer.

It took several dives to relocate the wreck of the USS Johnston, but then Victor Vescovo, along with engineer Shane Eigler on one dive and naval historian Parks Stephenson on another, were able to spend time surveying and filming the destroyer.

Samar island, Philippines with the GeoGarage platform (NGA nuatical raster chart)

Mr Vescovo said that the hull number – 557 – was clearly visible on both sides of its bow, and two full gun turrets were also intact.

“The gun turrets are right where they're supposed to be, they're even pointing in the correct direction that we believe that they should have been, as they were continuing to fire until the ship went down,” he explained.

“And we saw the twin torpedo racks in the middle of the ship that were completely empty because they shot all the torpedoes at the Japanese.”

Image copyright Victor Vescovo /Caladan Oceanic

Image copyright Victor Vescovo /Caladan Oceanic

The team is now working with naval historians in the hope of shedding more light on the World War Two battle.

The relatively small USS Johnston was heavily outnumbered by the Japanese fleet, which included Japan’s largest battleship, but was awarded for its courage under heavy fire

Of the crew of 327, only 141 survived the battle.

No human remains or clothing were found during the expedition, and the team laid wreaths before and after the dives.

“The gun turrets are right where they're supposed to be, they're even pointing in the correct direction that we believe that they should have been, as they were continuing to fire until the ship went down,” he explained.

“And we saw the twin torpedo racks in the middle of the ship that were completely empty because they shot all the torpedoes at the Japanese.”

Image copyright Victor Vescovo /Caladan Oceanic

Image copyright Victor Vescovo /Caladan OceanicThe team saw two forward gun mounts during the dive

The team is now working with naval historians in the hope of shedding more light on the World War Two battle.

The relatively small USS Johnston was heavily outnumbered by the Japanese fleet, which included Japan’s largest battleship, but was awarded for its courage under heavy fire

Of the crew of 327, only 141 survived the battle.

No human remains or clothing were found during the expedition, and the team laid wreaths before and after the dives.

Links :

With swarms of ships, Beijing tightens Its grip on South China Sea

A satellite photo of Whitsun Reef on March 23.

At one point in March, 220 Chinese ships were reported to be anchored around the reef.

At one point in March, 220 Chinese ships were reported to be anchored around the reef.

Credit...Maxar Technologies

From NYTimes by Steven Lee Myers and Jason Gutierrez

After building artificial islands, China is using large fleets of ostensibly civilian boats to press other countries’ vessels out of disputed waters.

The Chinese ships settled in like unwanted guests who wouldn’t leave.

As the days passed, more appeared.

They were simply fishing boats, China said, though they did not appear to be fishing.

Dozens even lashed themselves together in neat rows, seeking shelter, it was claimed, from storms that never came.

Not long ago, China asserted its claims on the South China Sea by building and fortifying artificial islands in waters also claimed by Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia.

Its strategy now is to reinforce those outposts by swarming the disputed waters with vessels, effectively defying the other countries to expel them.

The goal is to accomplish by overwhelming presence what it has been unable to do through diplomacy or international law.

And to an extent, it appears to be working.

“Beijing pretty clearly thinks that if it uses enough coercion and pressure over a long enough period of time, it will squeeze the Southeast Asians out,” said Greg Poling, the director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, which tracks developments in the South China Sea.

“It’s insidious.”

China’s actions reflect the country’s growing confidence under its leader, Xi Jinping.

They could test the Biden administration, as well as Beijing’s neighbors in the South China Sea, who are increasingly dependent on China’s strong economy and supply of Covid-19 vaccines.

The latest incident has unfolded in recent weeks around Whitsun Reef, a boomerang-shaped feature that emerges above water only at low tide.

At one point in March, 220 Chinese ships were reported to be anchored around the reef, prompting protests from Vietnam and the Philippines, which both have claims there, and from the United States.

Chinese vessels anchored March 27 at Whitsun Reef, a boomerang-shaped feature that emerges above water only at low tide.

Credit...Philippine Coast Guard

The Philippine defense secretary, Delfin Lorenzana, called their presence “a clear provocation.” Vietnam’s foreign ministry accusedChina of violating the country’s sovereignty and demanded that the ships leave.

By this past week, some had left but many remained, according to satellite photographs taken by Maxar Technologies, a company based in Colorado.

Others moved to another reef only a few miles away, while a new swarm of 45 Chinese ships was spotted 100 miles northeast at another island controlled by the Philippines, Thitu, according to the satellite photos and Philippine officials.

“The Chinese ambassador has a lot of explaining to do,” Mr. Lorenzana said in a statement on Saturday.

The buildup has inflamed tensions in a region that, along with Taiwan, threatens to become another flash point in the intensifying confrontation between China and the United States.

Although the United States has not taken a position on disputes in the South China Sea, it has criticized China’s aggressive tactics there, including the militarization of its bases.

For years, the United States has sent Navy warships on routine patrols to challenge China’s asserted right to restrict any military activity there — three times just since President Biden took office in January.

Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken expressed support for the Philippines over the presence of the Chinese vessels.

“We will always stand by our allies and stand up for the rules-based international order,” he wrote on Twitter.

The buildup has highlighted the further erosion of the Philippines’ control of the disputed waters, which could become a problem for the country’s president, Rodrigo Duterte.

The country’s defense department dispatched two aircraft and one ship to Whitsun Reef to document the buildup but did not otherwise intervene.

It is not known whether Vietnamese forces responded.

A satellite image over Whitsun Reef on March 23.

Credit...Maxar Technologies

A satellite image over Whitsun Reef on March 28.

Credit...Maxar Technologies

Critics say China’s disregard for the Philippine claims reflects the failure of Mr.

Duterte’s efforts to cozy up to the Communist Party leadership in Beijing.

“People need to hear from the commander in chief himself, a coward to China but a bully to his own people,” said Mr. Duterte’s staunchest political opponent, Senator Leila de Lima.

Mr. Duterte has not publicly addressed the matter, though his spokesman suggested that quiet efforts to defuse the situation were underway.

China has brushed off the protests.

A spokeswoman for the foreign ministry, Hua Chunying, said that Chinese fishermen “have been fishing in the waters near the reef all along.”

Officials in the Philippines and experts said there was no evidence of that.

Whitsun Reef is part of an atoll known as Union Banks, about 175 nautical miles from Palawan, a Philippine island.

The Philippines, China and Vietnam each claim that the atoll lies within their country’s exclusive economic zones, but only China and Vietnam have established a regular physical presence there, giving each a secure, if not legal, advantage in asserting control.

Vietnam has occupied four islets in the atoll since the 1970s, while China has built two outposts on previously submerged reefs as part of its program, underway since 2014, to dredge up seven artificial islands.

Two of the outposts — Grierson Reef, occupied by Vietnam, and Hughes Reef, occupied by China — are less than three nautical miles apart.

Whitsun Reef is part of an atoll known as Union Banks, about 175 nautical miles from Palawan, a Philippine island.

The Philippines, China and Vietnam each claim that the atoll lies within their country’s exclusive economic zones, but only China and Vietnam have established a regular physical presence there, giving each a secure, if not legal, advantage in asserting control.

Vietnam has occupied four islets in the atoll since the 1970s, while China has built two outposts on previously submerged reefs as part of its program, underway since 2014, to dredge up seven artificial islands.

Two of the outposts — Grierson Reef, occupied by Vietnam, and Hughes Reef, occupied by China — are less than three nautical miles apart.

Filipino fishermen in 2016 near Scarborough Shoal, a reef that China and the Philippines both claim.

Credit...Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

An international tribunal convened under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea ruled in 2016 that China’s expansive claim to almost all of the South China Sea had no legal basis, though it stopped short of dividing the territory among its various claimants.

China has based its claims on a “nine-dash line” drawn on maps before the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

A Philippine patrol first reported the large number of ships at Whitsun Reef on March 7.

According to Mr. Poling, satellite photographs have shown a regular, though smaller, Chinese presence over the past year at the reef.

By March 29, 45 ships remained at Whitsun, according to a statement on Wednesday by the National Task Force-West Philippines Sea, an agency that reports to the Philippine president’s office.

The task force counted 254 ships as well as four Chinese warships that day in the Spratlys, an archipelago of more than 100 islands, cays and other outcroppings between the Philippines and Vietnam.

The task force said the 254 ships were not fishing vessels, as Beijing claimed, but part of China’s maritime militia, an ostensibly civilian force that has become an integral instrument of China’s new maritime strategy.

Many of these boats, while unarmed, are operated by reservists or others who carry out the orders of the Coast Guard and People’s Liberation Army.

“They may be doing illicit activities at night and their lingering (swarming) presence may cause irreparable damage to the marine environment,” the task force’s statement said.

Aboard a U.S. Navy reconnaissance plane in 2018 as it observed the buildup of islands by China in the South China Sea.

Credit... Adam Dean for The New York Times

The presence of so many Chinese ships is meant to intimidate.

“By having them there, and spreading them out across these expanses of water around the reefs the others occupy, or around oil and gas fields or fishing grounds, you are steadily pushing the Filipinos and the Vietnamese out,” Mr. Poling said.

“If you’re a Filipino fisherman, you’re always getting harassed by these guys,” he said.

“They’re always maneuvering a little too close, blowing horns at you.

At some point you just give up and stop fishing there.”

Patrols and statements aside, Mr. Duterte’s government does not seem eager to confront China.

His spokesman, Harry Roque, echoed the Chinese claims that the ships were merely sheltering temporarily.

“We hope the weather clears up,” he said, “and in the spirit of friendship we are hoping that their vessels will leave the area.”

The Philippines has become increasingly dependent on Chinese trade and, as it fights the pandemic, largess.

On Monday, the first batch of Covid-19 vaccines arrived in Manila from China with great fanfare.

As many as four million doses are scheduled to arrive by May, some of them donations.

China’s ambassador, Huang Xilian, attended the vaccines’ arrival and later met with Mr. Duterte.

“China is encroaching on our maritime zone, but softening it by sending us vaccines,” said Antonio Carpio, an outspoken retired Supreme Court justice who is expert in the maritime dispute.

“It’s part of their P.R.

effort to soften the blow, but we should not fall for that.”

Links :

- NYTimes :

China Fires Missiles Into South China Sea, Sending U.S. a Message / U.S. Says Most of China’s Claims in South China Sea Are Illegal / Duterte Plays Down Chinese Ramming of Philippine Fishing Boat

- Maritime Executive : "Illegal Structures" Spotted at Contested S. China Sea Reefs

- AMTI CSIS : Vietnam shores up its Spratly defenses / Force majeure : China's Coast Guard law in contect

- QT : Under the radar: China is 'gaslighting us' with sly move

- GeoGarage blog : China’s claims on the South China Sea are a warning to Europe

Wednesday, April 7, 2021

A nautical tradition fades with transition from printed to electronic charts

Robert Zaremba holds an original French nautical map of Cape Cod dating to 1757 next to a NOAA map from 1986 showing Chatham before the North Beach break at the Maps of Antiquity shop in Chatham.

From Cape Cod Times by Doug Fraser

When Michael Campbell first traveled on trans-Atlantic merchant vessels in the 1980s, they still used tools similar to those on board Columbus’ ship to find the angle of sun, moon and stars and calculate the ship’s position when it was out to sea beyond the range of the radar used for coastal navigation.

At 56, Campbell doesn’t consider himself an ancient mariner, but the cadets he takes on training cruises are more comfortable with the computer screens on the ship’s bridge than the sextant, the spanner or the chart room maps.

Freshman cadet Dylan Lydell, of Jamestown, N.Y., works on a NOAA paper chart as part of a navigation lesson on the bridge simulator at Massachusetts Maritime Academy.

NOAA is beginning the process of phasing out printed nautical charts in favor of electronic chart displays, such as the one to Lyndell's right.

NOAA is beginning the process of phasing out printed nautical charts in favor of electronic chart displays, such as the one to Lyndell's right.

“Every ship I was on prior to coming to the Massachusetts Maritime Academy used a combination of paper and electronics,” Campbell said.

“We’d put our position down on paper charts and keep them up to date.”

But he knows the next generation of cadets will likely not traverse the campus with a rolled-up chart under their arm, or plot a course at sea with a spanner and pencil lines on a chart table.

“In the future, we’ll get to where those paper charts go away,” Campbell said.

That future begins this August when the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration quietly turns the page on a 170-year history of printing nautical charts.

New York Bay and harbor (Coast Survey 1845)

The U.S. Coast Survey, now NOAA’s Office of Coast Survey, has been researching and printing charts since 1834.

Lake Tahoe with the GeoGarage platform (NOAA raster chart)

NOAA will begin to implement its sunset plan for paper nautical charts this month, starting w/ the current paper chart 18665, Lake Tahoe.

After August, NOAA’s electronic navigational chart will be the only NOAA nautical chart of the area.

Lake Tahoe’s paper chart No. 18665 the first to go

When NOAA retires Lake Tahoe’s paper chart No. 18665, it will be the first in a planned phase-out of their entire library of 1,000 paper nautical charts by 2025.

“It’s going to (fade away),” said James Deal, an instructor at New England Maritime for 25 years.

The Hyannis-based school offers maritime instruction and Coast Guard captain's license courses.

It’s part of an international movement away from the charts that have been guiding mariners since 13th Century Mediterranean seafarers committed so-called "sailing instructions" and geographical renderings to stretched calfskin, with lines between ports that corresponded to wind and compass direction.

In 2016, the U.S. Coast Guard allowed commercial ships to use electronic charting systems instead of paper charts in U.S. waters.

By 2018, the International Maritime Organization required that most commercial vessels on international trips use electronic maps and navigation systems.

“Do I feel nostalgic? Absolutely, but I understand the value of technology and the safety and economy it brings,” Deal said.

When NOAA retires Lake Tahoe’s paper chart No. 18665, it will be the first in a planned phase-out of their entire library of 1,000 paper nautical charts by 2025.

“It’s going to (fade away),” said James Deal, an instructor at New England Maritime for 25 years.

The Hyannis-based school offers maritime instruction and Coast Guard captain's license courses.

It’s part of an international movement away from the charts that have been guiding mariners since 13th Century Mediterranean seafarers committed so-called "sailing instructions" and geographical renderings to stretched calfskin, with lines between ports that corresponded to wind and compass direction.

In 2016, the U.S. Coast Guard allowed commercial ships to use electronic charting systems instead of paper charts in U.S. waters.

By 2018, the International Maritime Organization required that most commercial vessels on international trips use electronic maps and navigation systems.

“Do I feel nostalgic? Absolutely, but I understand the value of technology and the safety and economy it brings,” Deal said.

Coast Survey made a few early chart-coloring efforts.

In this 1867 chart, increased clarity of details came at a twelve-cent cost increase

Sales of paper charts on the decline

The decision is driven by twin realities.

Merchant ships like the Ever Given, which got stuck in the Suez Canal recently, have gotten progressively bigger and require much more sophisticated and up-to-date information to navigate in areas where their margin of safety has correspondingly shrunk.

And the general boating public now relies almost exclusively on electronics.

“While most people are aware that keeping paper charts on board is a really good idea, I would guess that the vast majority of boaters don’t,” said Scott Zeien, owner of the Kingman Yacht Center in Cataumet.

The yacht center sells very few paper charts or chart books, he said.

NOAA data shows that electronic chart sales have doubled in the past decade to where over 900,000 were bought in the U.S. in 2019 and 2020, while paper chart sales were cut in half from just over 200,000 in 2010 to around 100,000 last year.

Paper charts can still be ordered through private map printing services, although NOAA will no longer update the traditional charts, only the maps printed from electronic ones.

But overall, fewer and fewer people will use them.

“Electronics have made it so easy," Zeien said.

"I keep a chart on my boat, but have I looked at it twice in the last five years? Probably not.”

But maps and the information they provide have power, said Robert Zaremba, co-owner of the Chatham store Maps of Antiquity.

They were the first things pirates grabbed when they boarded a vessel because the maps opened up harbors and trade routes to sailors who might otherwise have little local knowledge.

“If you can’t envision another part of the world without going there, you don’t have any power,” Zaremba said.

He likes the idea of maps that would correlate data he’d find useful, such as the areas where drunk drivers are most often stopped or cancer hotspots.

Modern electronic mapping does just that, with overlayed layers of information available at the push of a button.

Modern merchant vessels and cruise ships almost have too much flooding the electronic screens on their bridge, and even less need for paper maps, explained David Mackey, who chairs the Marine Transportation department at Massachusetts Maritime Academy.

They use what is known as an Electronic Chart Display and Information System (ECDIS).

Computer-driven, it melds GPS information with radar, depth finders, automated ship identification beacons, known hazards, navigational aids such as buoys and lighthouses and other navigational information onto one screen.

Coastal changes and new hazards can be updated quickly without having to wait for printing.

“ECDIS has so much data on so many pages with sub-pages and sub-menus, that mariners are required to take courses in general ECDIS training,” Mackey said.

There's so much data, the successful navigator needs to find the right mix so that the screen is useful, not cluttered.

It's no longer possible to walk onto a ship’s bridge with just paper chart navigation skills, he said.

“Every device has its time to be important,” Zaremba said.

His business is selling maps and charts, but it’s purely nostalgic.

“They are not using them on their hikes or on their boats.

People are framing them and putting them up on their walls,” he said.

But the past still has its place, experts say.

“There is value in knowing the feeling and mechanics of fixing a ship’s position,” Deal said.

Deal joined the Coast Guard at 18 and spent 30 years on active duty and in the reserves.

Satellite navigation was still in its infancy and celestial navigation and paper charts were an everyday routine.

“You can stare at a computer screen, but you have to fully interpret and comprehend what the system is telling you,” he saidl.

“A commercial airliner can fly itself, but a pilot needs to understand why the plane flies because there’s always a worst-case scenario that can occur.”

S102 Demonstrator showing a piloting scenario near Farsund in Norway.

The demonstrator is created by Kongsberg Digital, and is based on Kongsberg Digital's Cogs library for 3D visualization.

That’s why the Coast Guard still requires, for now, that those seeking licenses know how to use a paper chart.

Even though the systems are supposed to have backups, computers crash and electronics fail.

When you get into trouble, you have to know where you are and how to get to where you need to be.

Mackey, who is 63, teaches electronic navigation at the maritime academy, but can appreciate the reams of yellow legal paper he went through using spherical trigonometry to calculate a fuel- and time-saving Great Circle Route across the Atlantic.

He also knows the value of having eyes on the water, noting landmarks and the seamarks.

It all feeds into a knowledge base that can help future mariners truth-test the information they are getting from computer programs.

“They are far better than I am at manipulating (the ECDIS),” he said.

But he brings what he calls the “essence of navigation.”

“How do you not just rely on what it’s spitting out,” Mackey said.

Even though the systems are supposed to have backups, computers crash and electronics fail.

When you get into trouble, you have to know where you are and how to get to where you need to be.

Mackey, who is 63, teaches electronic navigation at the maritime academy, but can appreciate the reams of yellow legal paper he went through using spherical trigonometry to calculate a fuel- and time-saving Great Circle Route across the Atlantic.

He also knows the value of having eyes on the water, noting landmarks and the seamarks.

It all feeds into a knowledge base that can help future mariners truth-test the information they are getting from computer programs.

“They are far better than I am at manipulating (the ECDIS),” he said.

But he brings what he calls the “essence of navigation.”

“How do you not just rely on what it’s spitting out,” Mackey said.

Links :

Tuesday, April 6, 2021

Mapping the world’s key maritime choke points

From Visual Capitalist by Carmen Ang

Maritime transport is an essential part of international trade—approximately 80% of global merchandise is shipped via sea.

Because of its importance, commercial shipping relies on strategic trade routes to move goods efficiently.

These waterways are used by thousands of vessels a year—but it’s not always smooth sailing. In fact, there are certain points along these routes that pose a risk to the whole system.

Here’s a look at the world’s most vulnerable maritime bottlenecks—also known as choke points—as identified by GIS.

What’s a Choke Point?

Choke points are strategic, narrow passages that connect two larger areas to one another.

When it comes to maritime trade, these are typically straits or canals that see high volumes of traffic because of their optimal location.

Despite their convenience, these vital points pose several risks:

Despite their convenience, these vital points pose several risks:

- Structural risks: As demonstrated in the recent Suez Canal blockage, ships can crash along the shore of a canal if the passage is too narrow, causing traffic jams that can last for days.

- Geopolitical risks: Because of their high traffic, choke points are particularly vulnerable to blockades or deliberate disruptions during times of political unrest.

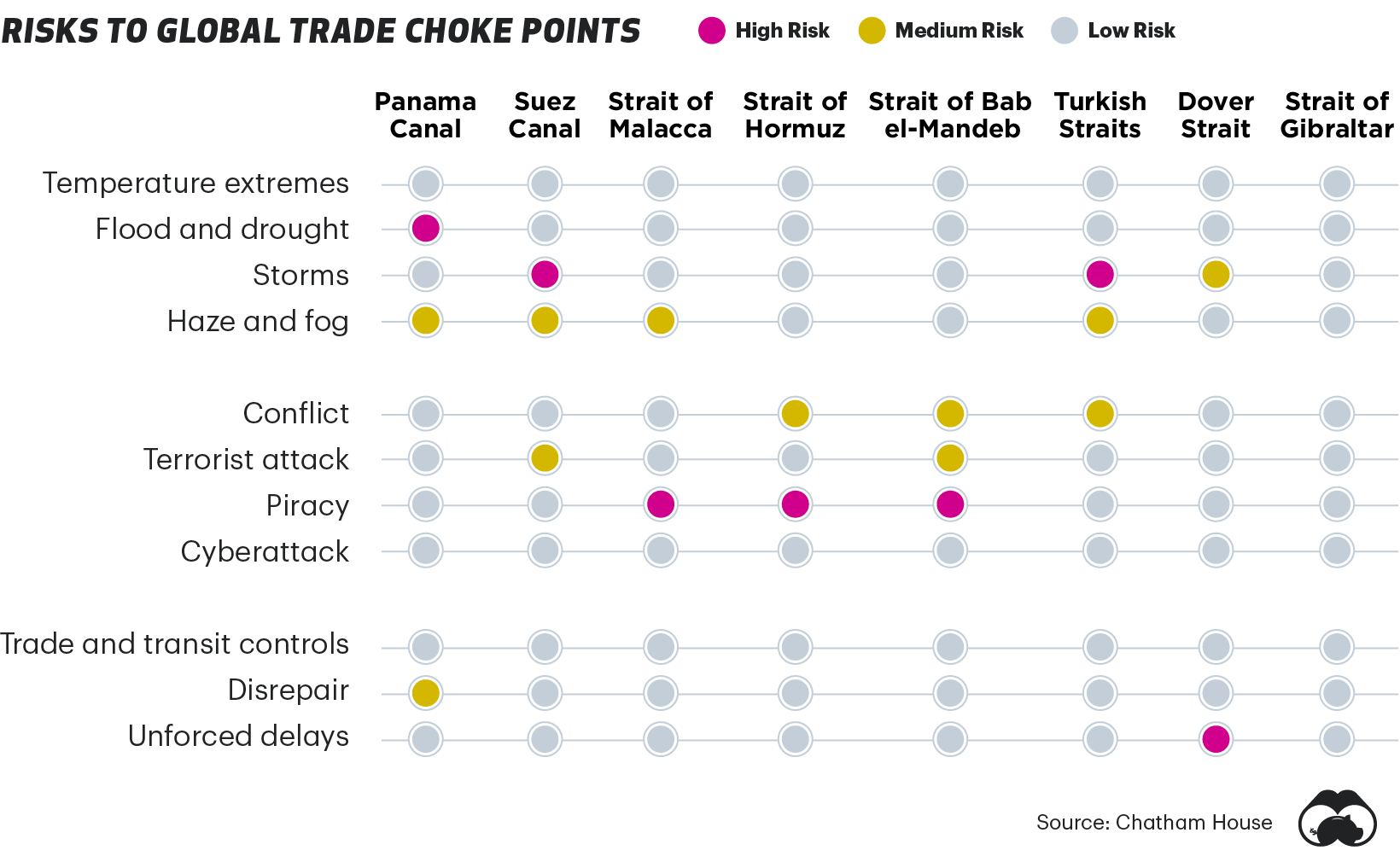

Here’s a look at some of the biggest threats, at eight of the world’s major choke points.

Because of their high risk, alternatives for some of these key routes have been proposed in the past—for instance, in 2013 Nicaraguan Congress approved a $40 billion dollar project proposalto build a canal that was meant to rival the Panama Canal.

As of today, it has yet to materialize.

A Closer Look: Key Maritime Choke Points

Despite their vulnerabilities, these choke points remain critical waterways that facilitate international trade.

Below, we dive into a few of the key areas to provide some context on just how important they are to global trade.

The Panama Canal

The Panama Canal is a lock-type canal that provides a shortcut for ships traveling between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Ships sailing between the east and west coasts of the U.S. save over 8,000 nautical miles by using the canal—which roughly shortens their trip by 21 days.

In 2019, 252 million long tons of goods were transported through the Panama Canal, which generated over $2.6 billion in tolls.

In 2019, 252 million long tons of goods were transported through the Panama Canal, which generated over $2.6 billion in tolls.

The Suez Canal

The Suez Canal is an Egyptian waterway that connects Europe to Asia.

Without this route, ships would need to sail around Africa, which would add approximately seven days to their trips.

In 2019, nearly 19,000 vessels, and 1 billion tons of cargo, traveled through the Suez Canal.

In an effort to mitigate risk, the Egyptian government embarked on a major expansion project for the canal back in 2015.

In an effort to mitigate risk, the Egyptian government embarked on a major expansion project for the canal back in 2015.

But, given the recent blockage caused by a Taiwanese container ship, it’s clear that the waterway is still vulnerable to obstruction.

The Strait of Malacca

At its smallest point, the Strait of Malacca is approximately 1.5 nautical miles, making it one of the world’s narrowest choke points.

Despite its size, it’s one of Asia’s most critical waterways, since it provides a critical connection between China, India, and Southeast Asia.

This choke point creates a risky situation for the 130,000 or so ships that visit the Port of Singapore each year.

The area is also known to have problems with piracy—in 2019, there were 30 piracy incidents, according to private information group ReCAAP ISC.

The area is also known to have problems with piracy—in 2019, there were 30 piracy incidents, according to private information group ReCAAP ISC.

The Strait of Hormuz

Controlled by Iran, the Strait of Hormuz links the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman, ultimately draining into the Arabian Sea.

It’s a primary vein for the world’s oil supply, transporting approximately 21 million barrels per day.

Historically, it’s also been a site of regional conflict.

Historically, it’s also been a site of regional conflict.

For instance, tankers and commercial ships were attacked in that area during the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s.

The Bab el-Mandeb Strait

The Bab el-Mandeb Strait is another primary waterway for the world’s oil and natural gas.

Nestled between Africa and the Middle East, the critical route connects the Mediterranean Sea (via the Suez Canal) to the Indian Ocean.

Like the Strait of Malacca, it’s well known as a high-risk area for pirate attacks.

Like the Strait of Malacca, it’s well known as a high-risk area for pirate attacks.

In May 2020, a UK chemical tanker was attacked off the coast of Yemen–the ninth pirate attack in the area that year.

Due to the strategic nature of the region, there is a strong military presence in nearby Djibouti, including China’s first ever foreign military base.

Due to the strategic nature of the region, there is a strong military presence in nearby Djibouti, including China’s first ever foreign military base.

Monday, April 5, 2021

Solo sailing on the Sea of Cortez

Morning light finds Liberte anchored under the rock formations of Bahía San Carlos.

David Kilmer

From CruisingWorld by David Kilmer

A sailor revisits old cruising grounds south of the border, where he relaunches his boat and embarks on a few days of exploring this wild coast of Mexico.

I had a small adventure of the grandest kind in November 2019.

I arrived by air in San Carlos, Mexico, where I launched my Beneteau 361, Liberte, into the northern Golfo de California, better known, perhaps, as the Sea of Cortez.

For the next 10 days I sailed alone through one of my favorite cruising grounds on the planet.

The sailing began, like many good trips, with a pre-dawn start.

Bahia San Carlos with teh GeoGarage platform

I woke at 0344, just before my alarm.

The tools of the trade lay where I’d placed them: headlamp, life jacket, personal locator beacon and harness.

By the headlamp’s red light, I started the Yanmar engine, readied the North main and hauled the Manson anchor, all familiar allies I’d been away from for too long.

I paused for a moment to take it all in.

I paused for a moment to take it all in.

There were dark cliffs on either side, with the sharp smell of guano from the rocks.

The moon was just setting, and by its pale light I could make out the twin peaks of Mount Tetakawi above.

Six days earlier, Liberte had been high and dry.

Six days earlier, Liberte had been high and dry.

With help from local contractors—along with fellow sailors who were kind enough to offer rides to town—and several days of my own sweat equity, she’d been prepped, polished and provisioned.

Liberte’s hull now wore fresh coats of Ameron ABC 3 antifouling paint, with extra layers at the leading edges and waterline.

"What was I grateful for right then? Freedom to move. The consistency of water. This boat and the ability to guide it."

"What was I grateful for right then? Freedom to move. The consistency of water. This boat and the ability to guide it."David Kilmer

I’d slept the first night on board in the yard, climbing a ladder, happy to find that my boat had weathered summer well under the landscape fabric for shade.

There was the anticipated layer of Sonoran dust on deck.

Below, everything was just as expected.

I’d bought Pollo Loco chicken for the painters, and I took the leftovers down to the guard shack.

The night guard and I spoke primitive Spanish, sat on overturned buckets and ate with our hands, watching bats fly out of the desert.

We saved scraps for the boatyard cat.

After paying all those dues in boat bucks and labor (one boat buck = $1,000), I relished my first evening on the hook.

My neighbor was an Austrian named Peter who’d just bought an Endeavor 35 and was as stoked as can be.

I paddled over to his pride and joy, where we sipped well-aged tequila with sailors from around the world.

It was a nice welcome back to the cruising life.

Now in the dark I waved at Peter’s boat as I passed; nobody stirring at this hour.

I booted up the iPad mini, and a chart came to life.

Time of departure: 0400.

I hoisted the main hand-over-hand, leaving one precautionary reef.

Today’s job was to take Liberte 74 miles west across the Sea of Cortez.

Highlights of the solo trip include hours at the helm, sailing along the Sierra de la Giganta mountain range.

Highlights of the solo trip include hours at the helm, sailing along the Sierra de la Giganta mountain range.David Kilmer

A wave rocked the boat.

An inland sailor in summer, I felt my body adjust to the motion.

More waves came, refracted around the headland, and then gusts of wind in the dark.

I grinned.

Lately I’d made a point to pay close attention, moment by moment,

to everything, including my response to those things.

Sailing was a way to hone that attention.

When I felt unsettled, I’d grin and be grateful.

I’d look at everything, as author Betty Smith says, as if seeing it either for the first or last time.

What was I grateful for right then?

Freedom to move.

The consistency of water.

This boat and the ability to guide it.

Onward, then, trimming the main to the new wind as I cleared the point, looking back at the lights of shore, just once, then ahead into trackless waters, pretending I was bold Joshua Slocum off to hurdle the globe.

Or any adventurer from the books I adored as a boy.

I don’t lay awake longing for Arctic ice or infamous capes, but I’m crazy for outings like this. I love the planning, the preparation and the little voyage itself.

Being solo, I was discovering, further sharpened everything.

A beam wind now, and I could unfurl the jib and shake out the main.

The boat felt great in my hands.

The wind instruments were acting up again, so I sailed seat-of-the-pants, sensing subtle changes and responding.

I kind of liked it this way anyway.

Just days ago, these sails were in bags, lines bundled, Liberte lonely and landbound.

Now she was on the move again, at play in the elements, and I was fortunate to be along for the ride.

I shut down the engine, and it was just my boat, the wind and me.

Paddling amid the spires at San Juanico.David Kilmer

Paddling amid the spires at San Juanico.David KilmerLand was shrinking astern, with all its information, obligation and illusion.

Now the only thing was to coax the boat along her cantering path and stay connected with her.

Alone, with thousands of feet of water below me.

Destination: unfamiliar.

Now was as good a time as ever for dread.

Or, instead, to allow that separation from shore to strip away all the detritus of ordinary life.

I took some sharp breaths into my belly, ready for action.

I checked on my little realm: harness clipped like I promised my sweetheart, sails trimmed and pulling nicely, lines flaked, and autohelm steering the proper course.

What would my mentor Gartly do?

He’s the pied piper who first lured me to sea; he’d told me last night when I texted him my float plan, “Enjoy the stars.”

So I did.

So I did.

I stretched out on my back, hands laced behind my head, and contemplated the unspoiled night sky.

I gazed up at Orion, Taurus, and those lovely and coy Pleiades.

Then I saw a UFO.

At first I thought it was a satellite, but it was moving way too fast.

It stopped, jumped and stopped again. Then it was gone.

Arriving back in Mexico, the first order of business is to get Liberte cleaned, polished and painted.David Kilmer

Arriving back in Mexico, the first order of business is to get Liberte cleaned, polished and painted.David KilmerDawn came under the clouds and painted the edges of everything.

I grinned again, this time from genuine pleasure.

After 15 years and plenty of cruising miles, I knew this boat profoundly.

All her parts and pieces held their stories. I’d learned my way through systems stem to stern, and the rest would be on the punch list soon enough.

How beautifully she purred along! I knew better than to touch a thing.

Instead I did some shadow boxing and cockpit calisthenics.

I thoroughly enjoyed a bowl of homemade granola that had been tucked into my sea bag, my girl’s loving way of keeping some meat on my sailor bones.

The wind was remarkably steady, the right choice made to sail today on the tail end of a norther, between too much wind yesterday and none tomorrow.

I felt, as always in prime conditions, as though I were getting away with something.

The sun paced me lazily behind clouds.

Land began to appear in floating specks—there in the corner of the eye; gone if you looked right at it.

I saw no garbage and no other craft, just the faint smell of an oil rig on the wind for a long time before I could hear its far-off rumble.

Iconic sights in the Sea of Cortez include pelicans lining the shore at Bahía San Carlos searching for baitfish

Iconic sights in the Sea of Cortez include pelicans lining the shore at Bahía San Carlos searching for baitfishDavid Kilmer

I shouted poetry to the clouds and belted vintage songs in a voice that would have scared Tom Waits.

I considered, one by one, the extraordinary people I have been so fortunate to know.

I thought about those I love and have loved, their presence close out here in the empty reaches.

The north wind was a steady companion, and Liberte ticked off 1 nautical mile after another.

I was pleased to see stretches of 7-something knots for speed—a good day in any small cruising boat. I took the helm sometimes for the sheer fun of it.

The only time I changed gears was for a couple of slow-moving rain clouds.

“De rain kill de wind,” as the Bequia sailors used to say.

And then, there it was, the intended harbor, and I performed the rituals of arrival.

A look at the charts, the dowsing of sails, and I glided into the wide and placid protection of Bahia Santa Inéz.

The anchor touched sand at 1600 hours. A textbook passage, which is not always the case.

The boat rocked gently as I tidied up the deck, lovingly rubbing down my little steed after such a fine gallop.

The sunset was transcendental.

It began with chiaroscuro effect through the peaks of the Sierra de la Giganta.

Then the light turned gold and slowly purple as beams shot skyward.

That sunset continued to reach out across the water until it had engulfed my sailboat and me in an overwhelmingly beautiful moment.

I forgot every bit of time, boat bucks and worry I’d spent to be here. I simply was.

Fishermen at Isla Danzante casting their nets.

Fishermen at Isla Danzante casting their nets.David Kilmer

For the next week or so, I stayed in that blissful state.

I slept when tired and ate when hungry.

Doing my simple boat chores, I chopped wood and carried water, as the Zen koan goes.

Heading south down the Baja coastline, there were dozens of great anchorage options.

There are no ocean swells in the Sea of Cortez.

The wind waves can be steep during winter northers due to fetch and current, but this time of year, I had stellar weather.

I sailed every day on the afternoon sea breeze

I saw dolphins off the bow, whales in the distance and rays jumping out of the water.

It had rained more than usual recently, and the mountains were as green as I’d ever seen them.

In San Juanico, a splendid anchorage of rock spires and long empty beaches, I rambled into the hills and found the desert full of life.

There were flowers everywhere, along with butterflies, bees and birds. An osprey had nested on a strategic outcropping, the best real estate in the bay, and was working the shoreline for fish.

At Isla Danzante, near Loreto, I was tickled to find my favorite anchorage open: a one-boat corner of Honeymoon Cove.

If I weren’t in an alternate reality already, this place sealed my fate.

I spent hours clambering mindlessly around, watching the light change on the desert and the sea.

Thumb-size cactus thrived in the cleft of a rock, and fish bones lay where something had made a meal.

Dolphins off the bow near Loreto, making good company.David Kilmer

Dolphins off the bow near Loreto, making good company.David KilmerThere was another boat around the corner, and normally I would have stroked the paddleboard over to say hello, but I didn’t want to break the spell.

I saw huge schools of baitfish flashing in the clear water, with roosterfish hitting them from below while pelicans dived from above.

Most days I could empathize with those fish, but today I simply felt a part of it all—predator, prey and curious observer at the same time.

Cormorants took off, leaving dark rings in their wake.

A yellow-crowned night heron waited.

I was hopelessly enthralled.

Truth be told, I was perfectly at peace doing absolutely nothing there. I had guests to pick up soon, but I waited as long as possible.

That last night at the island, spent with just the critters and me, will be with me always.

As I chugged toward nearby Marina Puerto Escondido the next morning, I saw that I had come full circle.

As I chugged toward nearby Marina Puerto Escondido the next morning, I saw that I had come full circle.

Discovering the river slicing through the desert at San Juanico as a reward for taking a hike.

Discovering the river slicing through the desert at San Juanico as a reward for taking a hike.David Kilmer

This harbor was the first place I’d ever stepped foot on a cruising boat.

As a young man, I’d coaxed a battered Toyota pickup down Highway 101, stacked it high at San Diego’s chandleries, and hauled my contraband south to meet Gartly’s Cal 34, Marlin, at this very seawall.

From here, I’d helped him prep Marlin and sail her partway across the Pacific.

My life had never been the same.

In good times and bad on boats, I can always blame Gartly for that.

“Back to the scene of the crime,” I said out loud to nobody.

I realized it had been a while since I’d talked to anyone but birds and dolphins.

“Back to the scene of the crime,” I said out loud to nobody.

I realized it had been a while since I’d talked to anyone but birds and dolphins.

Maybe I was due for some human contact. I swung the bow toward what we call civilization.

After several seasons of East Coast cruising, David Kilmer and Liberte are back in Pacific Mexico.

After several seasons of East Coast cruising, David Kilmer and Liberte are back in Pacific Mexico.

Links :

- The Guardian : Whale watching in Mexico - in pictures

Sunday, April 4, 2021

Oceanbird, a large retractable sail freighter to transport 7,000 cars at 10 knots

The 200 metres long and 40 metres wide cargo vessel will be able to cross the Atlantic in 12 days.

Oceanbird, a large retractable sail freighter to transport 7,000 cars at 10 knots

Oceanbird, a large retractable sail freighter to transport 7,000 cars at 10 knots

(Displacement: 32,000 ton)

The wing sails are all of 80 metres tall, giving the ship a height above water line of approx 100 metres, but thanks to a telescopic construction they can be lowered, resulting in a vessel height above water line of approx 50 metres.

This comes in handy when passing under bridges or if the surface area of the wingsails needs to be reduced due to strong winds.

To be able to get in and out of harbours – and as a safety measure – the vessel will also be equipped with an auxiliary engine.

Powered by clean energy, of course.

The first vessel will be a cargo ship, but the concept can be applied to ships of all types, such as cruise ships.

This comes in handy when passing under bridges or if the surface area of the wingsails needs to be reduced due to strong winds.

To be able to get in and out of harbours – and as a safety measure – the vessel will also be equipped with an auxiliary engine.

Powered by clean energy, of course.

The first vessel will be a cargo ship, but the concept can be applied to ships of all types, such as cruise ships.