He has just published on Twitter a timelapse that allows you to see the evolution of the Banc d'Arguin from 1984 to today in a few seconds, as well as the urbanisation of La Teste during this 36-year period.

Saturday, November 21, 2020

Banc d'Arguin : time-lapse of the evolution during 36 years

He has just published on Twitter a timelapse that allows you to see the evolution of the Banc d'Arguin from 1984 to today in a few seconds, as well as the urbanisation of La Teste during this 36-year period.

Friday, November 20, 2020

Preparing for rising sea levels

Image Credits: Pixabay, Climate Central, NOAA climate.gov, Climate Central.

From Climate Foresight by Francesco Bassetti

Rising sea levels is one of the risks that people most commonly associate with global warming, with more than 600 million people (around 10% of the world’s population) living in coastal areas that are less than 10 meters above sea level.

“What we need is a cross-sectoral approach that faces and solves problems related to sea level rise with a systemic vision of risks that then shares possible actions between different actors.

Considering multiple types of hazards reduces the likelihood that risk reduction efforts targeting one type of hazard will increase exposure and vulnerability to other hazards, in the present and future.

Evaluating risk depends on an analysis of hazard (how much sea levels will rise), exposure (who and what will be affected) and vulnerability (who and what is particularly exposed to the effects).

Therefore, the threats presented by rising sea levels must be evaluated against the specific circumstances of each area.

With fellow researchers, Torresan is working on bringing this approach into policymaking, by applying a multi-criteria methodology to support the analysis and prioritization of risk management measures aimed at enhancing resilience towards climate change-related extreme events for the Metropolitan city of Venice in Northern Italy with the Savemedcoast2 project.Understanding how different land and sea-based drivers – natural and anthropic – shape the evolution of coastal zones at different spatial and temporal scales, and what solutions could be implemented to reduce vulnerability and mitigate environmental and socio-economic risks is of paramount importance to unlock sustainable development pathways.Silvia Torresan, CMCC Foundation

What does this mean for policy decisions?

When talking about sea level rise, accurate predictions are fundamental for both mitigation and adaptation policies.

For mitigation, knowing that different emissions pathways will have a direct effect on future sea levels can act as an added incentive for reducing emissions.

For adaptation, accurate predictions and a multi-risk approach can make all the difference when choosing what strategies to adopt and where and when to apply them.

“Different scenarios, when analysed one by one, lead to a specific prioritisation of the set of risk management measures; while, when the scenarios are analysed together, the prioritisation of the same measures can be totally different.

The necessity to adopt a multi-hazard approach to disaster risk management and climate change adaptation is confirmed by these outcomes developed in the Metropolitan city of Venice using a bottom-up approach with a strong stakeholders involvement in the frame of the BRIDGE project.

Implementing measures strongly oriented to cope with single hazard could lead to an increase of a risk towards other kind of hazards,” explains Anna Sperotto, scientist that at CMCC Foundation who focuses her research on Risk Assessment and Adaptation Strategies.

Furthermore, processes leading to adaptation are far more effective when they are inclusive: involving actors covering different sectors, stages and domains of risks and resilience management to ensure that the needs and perspectives of minority groups are also taken into account.

In this way, different system connections and interdependencies are fully understood.

CoastelDEM tool for mapping future sea level rise depicting a worst case scenario in northern Europe.

CoastelDEM tool for mapping future sea level rise depicting a worst case scenario in northern Europe.This is fundamental when talking about coastal planning around the world and not just in Venice.

Moderate future scenarios indicate that by 2050 the homes of 150 million people could find themselves permanently below the high-tide line.

And this is accounting for stability in the Antarctic.

If on the other hand an Antarctic instability outlook is assumed then a total of 300 million people are considered as currently living on land that is at risk.

Since 1880 global mean sea levels have risen by 21-24 cm, with a 3.6 millimetre rise per year between 2006-2015, which is more than twice as much as the average for the rest of the 20th century (1.4 millimetres per year).

As ocean and land temperatures continue to increase scientists are certain that sea levels will continue to rise.

However, the extent of this increment is still up for debate.

One source of uncertainty is the contribution of the Antarctic ice sheet.

The Summary for Policymakers for the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (#SROCC) 🌊 is now available in all UN languages:

— IPCC (@IPCC_CH) July 7, 2020

📘 https://t.co/INhkFDKDKr

🇬🇧 🇫🇷 🇨🇳 🇪🇸 🇦🇪 🇷🇺 pic.twitter.com/fZ9bWfSAen

The reason we are seeing updated figures and at times contrasting predictions has to do with the way in which sea level rise is calculated and the myriad of factors that must be taken into account.

However, to understand where and when sea level rise will impact specific areas and communities scientists must also collect accurate readings of land elevation against which to compare their data.

The most commonly used instrument for evaluating land elevation in the United States is the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM).

“I am very sensitive to this issue since I live in a very fragile coastal environment that is highly vulnerable to climate change, the city of Venice and its lagoon”, explains Torresan.The number of vulnerable provinces as well as the magnitude of vulnerability are expected to increase in the future due to the worsening of climate, environmental, and socio-economic conditions.Elisa Furlan, Climate risk, impact and vulnerability assessment scientist at the Euro-Mediterranean Center on Climate Change.

A new paper on risks associated with extreme sea level scenarios in Italy and how both natural and human drivers lead to both risks and vulnerability in coastal areas seeks to provide integrated knowledge and data with information on exposure and vulnerability.

Of particular significance is the paper’s choice to focus on the national scale so as to support policymakers by providing them with a “big vulnerability picture of Italian coasts as a whole and the vulnerability condition of individual coastal provinces.

Results indicate that “the number of vulnerable provinces, as well as the magnitude of vulnerability, are expected to increase in the future due to the worsening of climate, environmental, and socio-economic conditions (e.g. land use variations and increase of the elderly population).”

- FastCompany : NASA has a mind-blowing plan to map rising sea levels from space

- ScienceMag : Seas are rising faster than ever

Thursday, November 19, 2020

IHO reaches agreement on identifying seas with numbers amid East Sea naming row

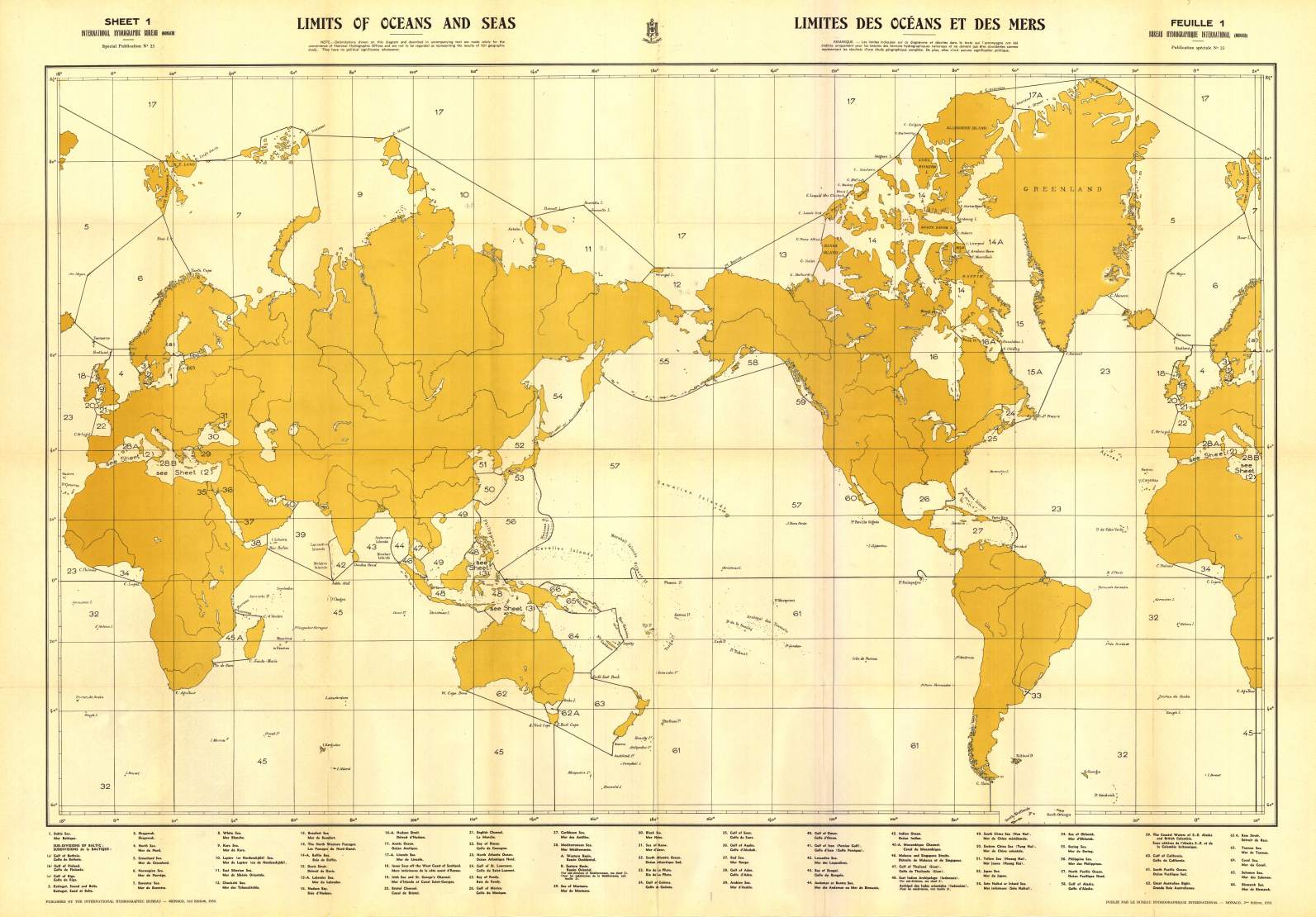

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) has reached agreement on a proposal to mark global sea areas with unique numerical identifiers rather than specific names, the foreign ministry said Tuesday.

The consensus, likely to be finalized early next month, capped decades of diplomatic efforts by Seoul to revise the existing IHO guidelines referring to the body of water between the Korean Peninsula and Japan only as the Sea of Japan, rather than the South Korean name East Sea.

During a virtual session of the IHO Assembly on Monday, 65 member states joined the discussions on the proposal to adopt a new digital dataset, known as S-130, as a standard for a world map of oceans, as the current one, dubbed S-23, remains outmoded.

IHO Secretary General Mathias Jonas has made the proposal amid persistent disputes over sea naming and other issues among IHO member states.

East Sea or Sea of Japan?

Numbers to replace specific names of seas

"Assembly Chair Marc Van der Donck said in the closing remarks that during the development of the new standards designating geographical sea areas only with unique numerical identifiers, the S-23 will be made public as an IHO publication to demonstrate the evolutionary process from the analogue to the digital era, and he concluded the proposal by consensus," the ministry said in a statement.

The ministry stressed that the participants accepted by consensus the original version of the IHO secretary general's proposal that the S-23 will be made public not as a valid standard but only as a publication displaying the evolutionary transition to a new one.

The ministry dismissed as "distortion" a Japanese news report that, based on the outcome of this week's IHO Assembly discussions, the Sea of Japan will continue to be used for international nautical charts, with the numerical identifiers used only for digital charts.

Detail of 1977 South Korean map that appears to be a copy of 1960 Japanese Coast Guard map

Detail of 1977 South Korean map that appears to be a copy of 1960 Japanese Coast Guard map

- Korea JoongAngDaily : Korea, Japan both claim victory as East Sea is relabeled by IHO

- JapanForward : Strange Korean Map Shows ‘East Sea’ Written for Two Different Water Bodies

- EastSea1994 : Reflections on the IHO S-23 and the Naming of East Sea

- EastSea Korea : Sea of Japan naming dispute

- GeoGarage blog : "Sea of Japan" "Sea of Korea" or "East Sea" / Japanese government urges boycott of ... / Dokdo island: A case study in Asia's ... / The naming of seas: the associated ... /

Japan offers archival evidence in island ...

Wednesday, November 18, 2020

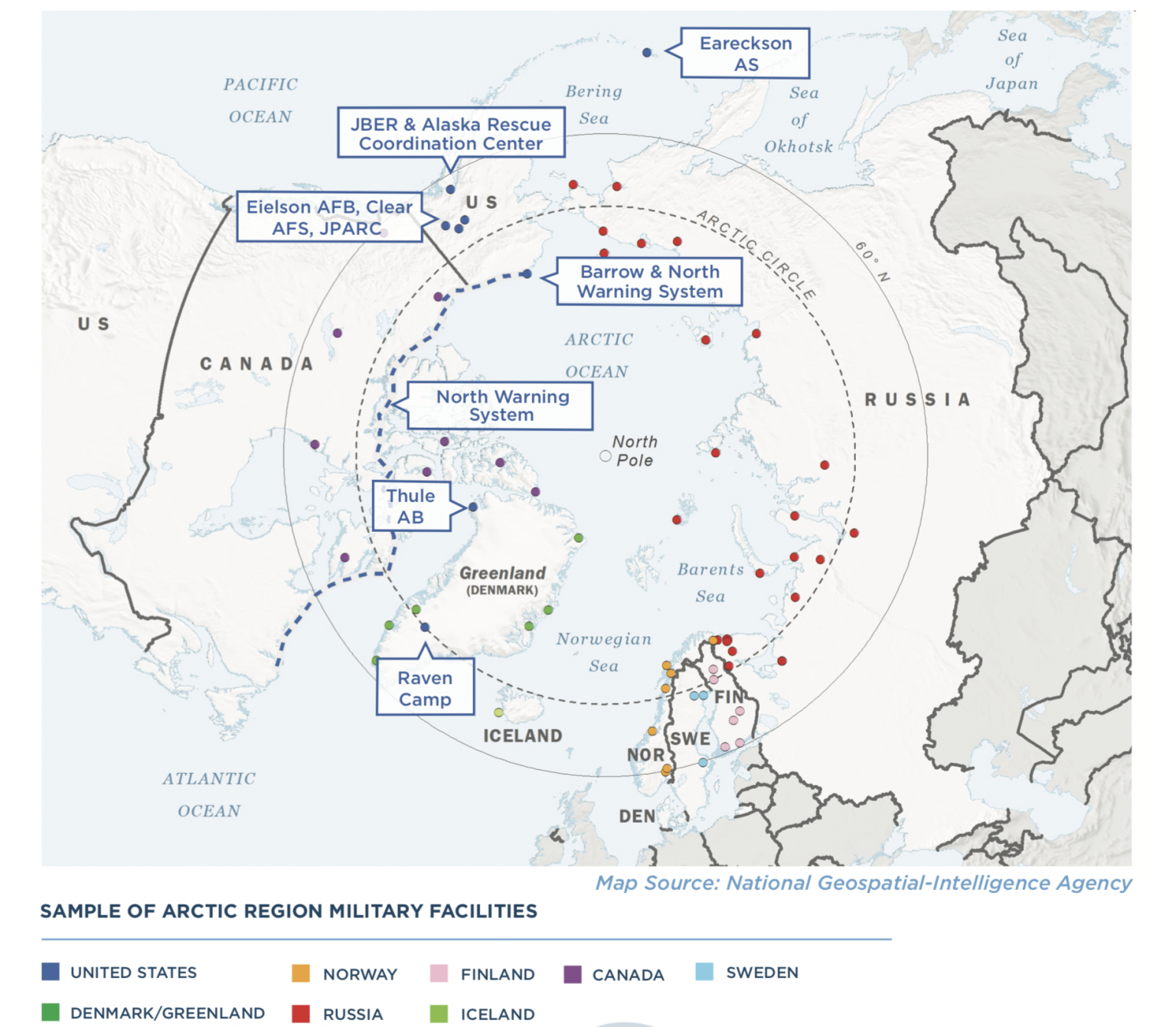

Why the Arctic is not the next' South China Sea

The South China Sea and the Arctic are increasingly grouped as strategic theaters rife with renewed great-power competition.

This sentiment permeates current affairs analysis, which features geopolitical links between the two maritime theaters.

And these assessments are not resigned to “hot takes” — the linkage features at senior policy levels, too.

Consider, for example, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s rhetorical question, “Do we want the Arctic Ocean to transform into a new South China Sea, fraught with militarization and competing territorial claims?”

To what extent are China’s challenges to maritime order in the South China Sea a signal for how it will approach the Arctic? Understanding the differences as well as the similarities between the South China Sea and Arctic geopolitical “competitions” is crucial to predicting the strategic implications of future maritime posturing and policies from Beijing.

Comparing the South China Sea flashpoint and the Arctic in the context of strategic competition highlights how maritime “revisionism” is better understood as maritime exceptionalism.

Yet comparisons often fail to provide an accurate picture of the internal geopolitical climates in each region, and we argue that it is too simplistic to extrapolate the trends in one theater and apply them to the other.

China and Russia approach the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in a localized and interest-based way when it comes to the South China Sea and Arctic regions.

These localized approaches to the law of the sea has implications for understanding challenges to multilateral rules-based governance of the global commons.

Both the South China Sea and Arctic are home to increasing great-power naval posturing, featuring active great powers intent on making maritime claims inconsistent with UNCLOS and asserting exceptional jurisdictional rights.

The unwillingness of the United States to ratify UNCLOS — while claiming that the portions of UNCLOS related to maritime claims have status and power as customary international law — makes the legal and institutional picture murkier.

Yet the extent to which the South China Sea and the Arctic are comparable as “contested commons” is limited.

First, there are crucial geographical differences.

Although the Arctic is the world’s smallest ocean, it is still five times larger than the South China Sea, and home to delineated maritime spaces and functioning rules of the game in the region.

The portion of the Central Arctic Ocean outside of claimed territorial waters and exclusive economic zones is roughly the size of the Mediterranean Sea.

Despite popular connotations of “new Cold Wars” and clashes in the Arctic, the region is home to long-standing maritime agreements, many treaties (including on search and rescue, and oil spill responses) negotiated between and among Arctic states, and is governed by the consensus-based Arctic Council.

It is a zone in which the renewed tensions between Russia and the West are largely absent, and remains a region of international cooperation and coordination.

Five Arctic Ocean coastal states have exclusive economic zones which extend out into various seas (the Greenland, Norwegian, Barents, Kara, Laptev, East Siberian, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas) above the Arctic Circle, which in turn form the Arctic Ocean.

China has anointed itself as a “near-Arctic State,” viewing the Central Arctic Ocean as a global commons.

In contrast to the relative harmony and cooperation in the Arctic, the South China Sea is a hotbed of disagreement and competition.

Encompassing over 3 million square kilometers, the South China Sea is subject to a range of overlapping claims over land features and jurisdictions, including sovereignty over islands and rocks, control of low-lying features such as reefs and shoals, the classification of land features, control of resources, and freedom of navigation.

Contests over exclusive economic zones abound.

Furthermore, China claims “sovereign rights” within the nine-dash line (approximately 90 percent of the South China Sea), a claim which was quashed by the ruling of 2016 South China Sea Arbitral Tribunal.

Beijing has rejected and largely ignored that ruling.

Sovereignty disputes concern the ownership of the hundreds of features dotting the sea, including islands, rocks, reefs, submerged shoals, and low-lying elevations, some or all of which are claimed by China, Taiwan, Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia.

Sovereignty of these land features and their classification — as islands, rocks, or low-lying elevations — affect the rights to maritime resources, such as oil, gas, and fish.

The above five states, plus Brunei and Indonesia, claim exclusive economic zones and continental shelf in the South China Sea beyond their mainland and archipelagic baselines.

Under international law, these maritime zones entitle states to limited sovereign rights (i.e., to resources), rather than full sovereignty.

Strategic competition at sea has been at least partly driven by China’s rising naval militarization.

The South China Sea is considered a “near sea” and its geographic proximity to the mainland is central to the China’s strategic imagination and threat perception.

In addition to conventional concerns about territorial defense, the South China Sea is also important for China because of its nationalist claims to all of the tiny land features, and its desire to exploit resources such as oil, gas, and fish.

This has also contributed to the growing militarization of the South China Sea.

In addition, six of China’s 10 largest ports can only be reached via this body of water.

These geographical differences render it too simplistic to extrapolate the geopolitics of the South China Sea to the Arctic.

This is further illustrated by drilling down into the differences in the strategic trajectories in terms of the balance of power and international legal norms.

Beginning in 2014, China engaged in rapid, large-scale militarization and artificial island-building in the South China Sea, raising alarm about its capacities and willingness to restrict navigation and exert sea control of this localized area.

Despite pledging not to militarize the islands, China took advantage of the geographic isolation and limited surveillance of these remote features to build three large, mid-ocean airfields suitable for military aircraft in 2016.

While some other claimant states also engaged in artificial island-building and militarization activities, China played a substantial role in militarizing the South China Sea, for example in emplacing anti-ship missiles and long-range surface-to-air missiles on artificial islands, contesting the transit of warships, and using maritime paramilitary forces for surveillance and intimidation of non-Chinese vessels.

These activities have precipitated new concerns about China’s intentions, including whether it wants to push the United States out of the first island chain.

These actions have precipitated concerns that China aims to revise and supplant or ignore maritime rules, with follow-on consequences for regional order more generally.

They directly challenge U.S. naval supremacy in the region.

China’s actions threaten U.S. interests in freedom of navigation and undermine the global maritime order, which has enabled the U.S. Navy to project power and enforce free transit for decades.

By contrast, in the Arctic, balance-of-power realities and great-power politics are not new.

The region is no stranger to geopolitical competition — it was a crucial battleground during the Cold War, as it is the shortest distance for missiles to fly between the United States and Soviet Union.

Further, the Arctic represented a key flank for NATO and strategically critical sea line of communication for wartime replenishment between Europe and North America.

Since the Cold War, regional cooperation and U.S.-Russian ties have remained somewhat siloed from tensions beyond the Arctic.

While new players and prizes have emerged in the Arctic “great game,” regional cooperation remains.

Of course, the preexisting U.S.-Russian power balance in the Arctic is an important consideration when adding Beijing to the Arctic power mix.

U.S. Arctic policy in recent years has been revived as part of a broader focus on renewed great-power competition.

Under the Trump administration, there has been a litany of Arctic updates — the Department of Defense, Air Force, and Coast Guard have all tabled new arctic strategies.

Increasingly, China is employing geoeconomics, rather than rapid militarization as seen in the South China Sea, to tilt the balance of power in the Arctic.

Beijing uses campaigns targeted toward the Nordic states and within the resource sector to increase influence, legitimacy, and engagement in the Arctic region.

Chinese economic engagement in Greenland’s resource sector, as well as its growing (albeit ever so slightly) economic ties in Iceland and Norway, are illustrative of China’s efforts to expand its role in the Arctic economy.

Much of China’s foreign investment in Arctic energy ventures is targeted at the Russian Arctic zone — particularly the liquefied national gas projects on the Yamal Peninsula.

However, Kremlin awareness of the potential debt-trap diplomacy Beijing undertakes has resulted in a unified Russian policy to curtail majority ownership by China of any Russian Arctic ventures.

Efforts in the South China Sea to increase cooperation — such as code of conduct negotiations between China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or joint development plans — are failing to develop robust cooperative mechanisms for the management or resolution of maritime and territorial disputes.

In contrast, Washington’s balance-of-power considerations for the Arctic region tend to overstate the conflictual nature of the region — which, unlike its Cold War predecessor, is an environment characterized by international cooperation.

The U.S. interests are also different across the maritime theaters: In the South China Sea, the America’s primary interest has traditionally been cast as freedom of navigation and maintaining the capacity to maneuver within the first island chain, although recent diplomatic efforts have seen the United States provide more public support for the maritime rights of Southeast Asian claimant states.

In the Arctic, U.S. interests are primarily territorial, as it is one of five Arctic Ocean coastal states.

The Arctic is also a region through which Washington shares a border with Russia in the Bering Strait.

Additionally, there are vast resource interests in the Alaskan Arctic sector, an indigenous population, and strategic basing interests for power projection into the North Atlantic, Arctic, and Pacific Oceans.

Hydrocarbon (oil and natural gas) resource exploitation is a clear driver of the South China Sea and Arctic “great games.” The Arctic is often touted, as per the U.S. Geological Survey, to hold an estimated 30 percent of the world’s remaining gas and 13% of its untapped oil reserves.

Of course, the majority of these estimates fall within zones of the Arctic which are not disputed, clearly within delineated territories.

On the high seas of the Arctic Ocean, Chinese activity remains focused on scientific and research priorities, at least for now.

China is party to the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement, and while it is legally allowed to exploit the Central Arctic Ocean region, Beijing has continued to abide by the fisheries ban.

In the South China Sea, on the other hand, China has been aggressively attempting to deny Southeast Asian claimant states their legal entitlements to maritime resources under UNCLOS.

One of the contemporary challenges posed in the South China Sea are the so-called “gray zone tactics” employed by China’s paranaval forces to assert its claims to disputed land features and adjacent waters.

Described as a “cabbage strategy,” China’s maritime coast guard, fishing fleets, and maritime militia form layers of pressure that constitute its first line of maritime defense.

China’s proximity to the South China Sea allows it to use its growing number of maritime assets to implement its gray zone tactics to advance its claims.

In contrast, China’s naval capabilities are not yet advanced enough to project power in the more distant and complex Arctic high seas environment.

International Legal Norms

Distorting international legal norms is a central element of China’s South China Sea approach.

Although it has engaged in a “lawfare” strategy to support its territorial and maritime interests in the South China Sea, many of its pseudo-legal arguments are inconsistent with UNCLOS.

Possibly the highest profile are Beijing’s claims to “historic rights” inside the nine-dash line, which would give China sovereignty over land features as well as sovereign rights to fishing, navigation, and exploration and exploitation of resources.

This argument was rejected by an Arbitral Tribunal instituted under UNCLOS in 2016, which Beijing has refused to acknowledge as binding or legitimate.

The second ambit claim is China’s Four Sha (four sands) strategy, which involves constructing straight archipelagic baselines around the island groups of the Pratas Islands, Paracel Islands, Spratly Islands, and Macclesfield Bank.

Here, Beijing lawyers and academics have developed a new legal theory that the Four Sha are China’s historical territorial waters and part of its exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, even though the offshore archipelagos do not conform with standards for drawing straight archipelagic baselines set out in Article 47 of UNCLOS, which states that the ratio of the area of the water to the area of the land must be between one to one and nine to one.

In these South China Sea island groups, the water area is too large to meet these requirements.

Nevertheless, the Four Sha theory indicates a desire to claim internal waters within such baselines, which, if successful, would entitle China to full sovereignty over the area rather than the limited sovereign rights afforded in other maritime zones such as the exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.

The third concerning element of China’s lawfare strategy is the use of domestic law to justify double standards in implementing principles of freedom of navigation.

For example, the U.S. interpretation that innocent passage includes warships without prior notification is not universally shared.

Some legal scholars argue that the assertion of greater security rights at sea is a sign of creeping jurisdiction by coastal states .

For example, Beijing asserts its right to regulate foreign military activities in its claimed exclusive economic zone, contrary to widespread understandings of UNCLOS provisions.

Beijing has presented the South China Sea as a sui generis area subject to Chinese domestic law, rather than international law, which constitutes a form of jurisdictional exceptionalism.

Yet in the Arctic Ocean, Beijing has continued to adhere to the agreed international legal architecture, despite its increased footprint and interest in the region.

Like the South China Sea, the international shipping routes emerging from the melting Arctic zone are eyed by Beijing as a key component of the Polar Silk Road aspect of their Belt and Road Initiative.

For now, China looks to use the most viable Asia-to-Europe shipping passage — the Northeast Passage.

A large section of the Northeast Passage is Russia’s Northern Sea Route, an international waterway defined by Russian law.

In the Northern Sea Route, Russia has somewhat mimicked China’s jurisdictional exceptionalism in the South China Sea.

Russia argues that the Northern Sea Route constitutes “straits used for internal navigation,” and is thus not subject to all UNCLOS rights like innocent passage.

Russia’s application of UNCLOS Article 234 (commonly known as the ice law) stipulates that states can enhance their sovereignty and control over an exclusive economic zone if the area is subject to ice coverage or grounds for intensified environmental management.

Moscow has long applied this entirely legal approach and developed deeper jurisdictional exceptionalism in recent years.

Russia has crafted domestic laws and implemented strategies for the management of the Northern Sea Route.

Examples include laws requiring Russian pilotage of all vessels transiting through the Northern Sea Route, toll fees, and prior warning or indication of plans to use the route.

The United States makes its own tantalizing jurisdictional exceptionalism effort by refusing to ratify UNCLOS while expecting others to conform to it.

In a broad sense, the three great powers across these maritime regions — the United States, China, and Russia — appeal to jurisdictional exceptionalism, but such great-power privileges are applied inconsistently according to geography and interests.

Such exceptionalism has worrying implications for the capacities of global governance regimes to enforce global standards that apply to all states.

China defends its jurisdictional exceptionalism in the South China Sea, yet is slowly starting to reject Russia’s application of the same exceptionalism and historical argument for its Arctic exclusive economic zone.

This is particularly the case for the Northern Sea Route.

Beijing is increasingly opting not to refer to the Northern Sea Route at all, speaking merely in terms of the Northeast Passage.

While double standards are nothing new in international politics, it is interesting to witness the ways in which states pick and choose, manipulate, and artfully interpret international law to fit agendas.

It’s Geography, Stupid

There are clear indicators of Chinese revisionism at sea extending beyond the South China Sea into the Arctic.

Both regions are a portent for how agreed-upon international rules are applied in divergent ways across different settings toward diverse strategic outcomes.

Lumping the Arctic and South China Sea into one basket as theaters hosting Chinese maritime revisionism, as if the exact same strategy is unleashed in all maritime strategy, clouds the reality of the two regions’ distinct strategic environments.

A constant across both flashpoints is the significant role that geography plays.

Geographical proximity has allowed China to use the nine-dash line to justify an extension of its land boundaries out to sea.

This is a form of mapped territorialization which is now even implicating popular culture and media.

This is possible in large part due to the proximity of the South China Sea to mainland China.

Russia has also used geographical proximity to bolster domestic narratives of Arctic greatness and to justify its Northern Sea Route exceptionalism.

China’s 2018 Arctic Strategy flagged Beijing’s “near-Arctic” identity and has cemented Beijing’s strategic interest in the region, yet it is unlikely that a mapped territorialization will result in the Arctic.

Beijing’s lack of proximity to the Arctic is somewhat a revenge of geography that not only curtails China’s ability to legitimize itself amongst Arctic-rim powers, but is also a constraining factor for any domestic public relations agenda in China.

China’s Four Sha strategy is based on an assumption of sovereign ownership of contested land features in the South China Sea.

Russia, too, bases its extended continental shelf claim on contested features of the Arctic.

This claim is currently under consideration at the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf .

The underwater ridge which Russia argues is an extension of the Siberian continental shelf extends up to the North Pole along the Arctic Ocean seabed.

This ridge is also claimed by Denmark (by way of Greenland) and Canada.

The three states will likely deliberate between themselves any extended exclusive economic zone claims, given that the commission is unable to award territory and merely rules on the scientific evidence presented.

Contested land features are a hallmark of the current overlapping claims to the North Pole, but there is no avenue for China to tap into this particular contest of land features in the Arctic.

There is, however, the potential for China to claim ice floes in the high seas region of the Arctic Ocean — perhaps to even fortify or build its own floating feature in this region, climate change allowing.

In reality, this is unlikely due to the sheer operational challenges, none the least periods of 24-hour darkness, and a harsh operational environment which makes no commercial sense nor provides any limited strategic pay-off to repeating its South China Sea approach in the Arctic.

Overall, the South China Sea and the Arctic are very different maritime regions with distinct geopolitical characteristics.

China is clearly borrowing from the great-power exceptionalism playbook in the South China Sea.

Yet while Beijing has articulated a clear strategic interest in the Arctic, a replication of its South China Sea play book in the Arctic is highly unlikely.

Maritime exceptionalism in approaches to UNCLOS are localized and interest-based according to geography, rather than generalized and values-based seeking wholescale revision of the “rules-based international order.”

- The organization for World peace : Climate Change, Geopolitics And The Arctic

Tuesday, November 17, 2020

Meet the fearless women sailors taking on the ‘Everest of the seas’

British skipper Miranda Merron, 51, trains aboard Campagne de France for the Vendée Globe 2020, an around-the-world solo sailing race.

British skipper Miranda Merron, 51, trains aboard Campagne de France for the Vendée Globe 2020, an around-the-world solo sailing race. Known as “the Everest of the seas,” the Vendée Globe is an extreme test of physical and psychological endurance in the face of primal nature, the journey averaging 26,000 nautical miles and three months.

Among the 33 skippers who set sail on November 8 are six women—the most in the race’s history.

A woman has never won, though some have come close.

Ellen MacArthur ended up in second place in the 2000-2001 edition, a day later than that year’s champ.

Davies just missed the podium, coming in fourth in the 2008-2009 race.

Here, the skippers must battle tempest-ravaged seas, house-sized swells, and icebergs—the race organizers actually set an “Antarctic Exclusion Zone” so that the racers stay north of dangerous ice areas.

“I’ve never seen another vessel.

There’s nobody,” says Merron, who’s been there three times in other contests.

Once the skippers skirt New Zealand, they are at the point farthest removed from any geographic landmass, farthest away from any kind of help in the event of a disaster.

The hazards are infinite.

Traveling at speeds of up to 30 knots, the boat can hit a wave so hard “it’s like a car crash,” Crémer explains, potentially hurling a skipper overboard.

Often the closest assistance is in the form of a competitor: Sam Davies was one of the skippers diverted during the 2008–2009 race to help Yann Eliès, after he broke his pelvis and leg in a horrific Indian Ocean accident.

Stories like Eliès’s are not uncommon.

Some have gone down in legend.

In 1993, Bertrand de Broc bit off his tongue when a loose rope hit him square in the face.

He used a needle and thread to sew it back together, guided by physician instructions delivered via telex, a World War II-era precursor to the fax machine.

In the 2000–2001 race, the mast on Yves Parlier’s boat broke off, or “dismasted”—a devastating situation for sailors—in the middle of the Indian Ocean.

Parlier managed to rebuild his rig, scavenging materials from his boat and in the flotsam surrounding Stewart Island, where he anchored off New Zealand.

But then he faced a bigger challenge: running out of food.

He survived on fish and seaweed—flavored with dried soup packets and washed down with a little red wine—and managed to complete the race after 126 days.

(But Parlier didn’t arrive last! Though the winner, Michel Desjoyeaux, crossed the finish line after 93 days, two skippers placed after Parlier.)

They were lucky.

The race has also been marked by tragedy—two competitors were lost at sea in the 1992–1993 edition.

It’s been a half-millennium since Ferdinand Magellan first circumnavigated the earth.

Like the legendary Portuguese explorer on his epic quest, the Vendée Globe’s skippers are sometimes reduced to living in animal-like conditions: sleeping in 20-minute intervals, crawling around on hands and knees, avoiding concussions.

But the food’s better; Crémer has a 90-day stock that includes duck pâté, chocolate, and flavorful dehydrated meals, while Merron has 100 days’ worth of tea and a freeze-dried Christmas feast.

Mind over matter

Besides the physical hardships, the mental strain can be immense.

Decision-making is hampered by sleep deprivation; emotions are amplified.

“For the first 24 hours, you hallucinate there’s someone else on board,” jokes Merron.

“The wind’s picking up and you’re wondering why the other person isn’t dealing with the sails.”

How do the competitors endure the seclusion, exhaustion, and stress? How do they confront fear aboard their 60-foot boats? Managing sleep is a crucial component of the race, with some skippers working with university researchers to fine-tune their strategies.

“The rule is: You just sleep whenever you can,” explains Merron.

“You have to be on watch.

The radar has an alarm but conditions [on the ocean] change all the time.”

|

Clarisse Crémer, 30, on Banque Populaire X tacks across a wave. In the Vendée Globe, skippers must complete the race on their own. PHOTOGRAPH BY YVAN ZEDA, VENDEE GLOBE 2020 |

Crémer combats the stress through yoga and sophrology, the breathing and meditation practice.

In past outings, she found an outlet by making social media videos from her boat, conveying humor and infectious enthusiasm in her footage.

She continued filming this year, when the pandemic lockdown in France prevented skippers from training on the water.

She recorded elaborate recreations of life at sea, clad in foul weather gear, miming the motions, while her companion hurled buckets of water at her.

The camera has become a psychological tool to help Crémer brave not just the race’s extreme conditions, but also the unknown pitfalls.

Crémer insists that you can’t think of the overall, big-picture challenge.

“In French we have an expression: A chaque jour suffit sa peine,” she says, which translates as: “Each day has enough trouble of its own.

Take it day by day.” “When you have a goal that’s really hard to attain, it’s imperative to move forward step by step.

Concentrate on a smaller task, a smaller, achievable goal.”

Merron looks at the dangers with practicality.

“I have a saying, if nothing’s gone wrong in a 24-hour period, you have to be wary.” But she’s looking forward to the freedom, away from the Internet, “being on the ocean, exploring the last places on earth that mankind hasn’t completely sullied … Though there’s so much rubbish floating in the sea.”

The biggest fear for Davies is not finishing the race.

In 2012 she dismasted and had no choice but to cut free the rigging to save her boat from sinking.

“Failure is the other side of adventure,” she says.

Pioneering women

Physical strength and mental fortitude are important foundations, but these women have wind in their sails thanks to those who came before them.

“My mum sent me to a talk by Dame Naomi James when I was nine and I was absolutely enthralled,” Merron says of the first woman to have sailed single-handed around the world via the Cape Horn route in 1978.

As an adult, Merron sailed with a then 23-year-old Davies on Maiden under Tracy Edwards, who had recruited the first all-women crew to attempt the Jules Verne Trophy, a prize for the fastest circumnavigation.

“The reason why I’m here is Tracy Edwards,” says Davies.

“She was not only my hero, but she also opened so many doors for women in sports.

A younger me, when I watched her race, never would’ve imagined that one day I’d be on her crew.”

The first women to participate in the Vendée Globe were Isabelle Autissier and Catherine Chabaud, renowned French navigators and ocean racers.

Pummeled by gales, the 1996–1997 race was a saga of disaster and tragedy.

Yet Chabaud placed sixth (140 days).

(Autissier crossed the finish line but was disqualified because of a stop in Cape Town to repair a damaged rudder.

She had turned around in a storm to search for competing Canadian skipper Gerry Roufs, lost at sea and presumed dead.)

Four years later Ellen MacArthur clinched second place in the Vendée Globe.

The 24-year-old British skipper nearly caught Michel Desjoyeaux, who beat her by a single day (93 days).

“To see her race was really interesting,” explains Crémer of one of her role models, “she’s not exactly a tall person with big muscles!”

It was a different century altogether when a woman first dared take up the challenge of beating the circumnavigation record of Phileas Fogg, the fictional hero of Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days.

Nellie Bly was a 19th-century investigative journalist who invented a new kind of “stunt reporting” when she had herself admitted as a patient to a women’s insane asylum in order to expose the terrible conditions there.

Her articles sold newspapers, with her name soon promoted in the headline itself.

Hungry for maritime adventure, she convinced her editor at New York World to sponsor the trip, via steamship and train, which she accomplished in 72 days, a world record in 1890.

Her voyage—filled with jolly captains, a pet monkey, and even a visit with Verne himself—is far from the perilous, solitude-enforced Vendée Globe.

But her perseverance, ambition, and spirit—only traveling with one dress to minimize luggage, charming the smallpox quarantine doctor in San Franciscoharbor—conjures present-day adventurers.

Bly’s published telegrams mesmerized the public, alongside the newspaper’s contest for readers to guess at her trip progress.

Her one regret, she wrote later, was that “in my hasty departure I forgot to take a Kodak.”

The Vendée Globe competitors won’t forget their cameras.

They record their adventures with humor and wit, using today’s communication channels: video and social media.

Samantha Davies famously shot a video of herself dancing to Cyndi Lauper’s “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun” as she sailed into the Northern Hemisphere in the 2008–2009 race.

On a previous solo transatlantic crossing, Crémer lip-synced to a medley of French and English pop hits.

“With the current pandemic situation, with less entertainment and canceled events, we sense that spectators are keen to follow us this year,” explains Davies.

“And that is a huge motivation.”

Links :

- GeoGarage blog : Vendee Globe

Monday, November 16, 2020

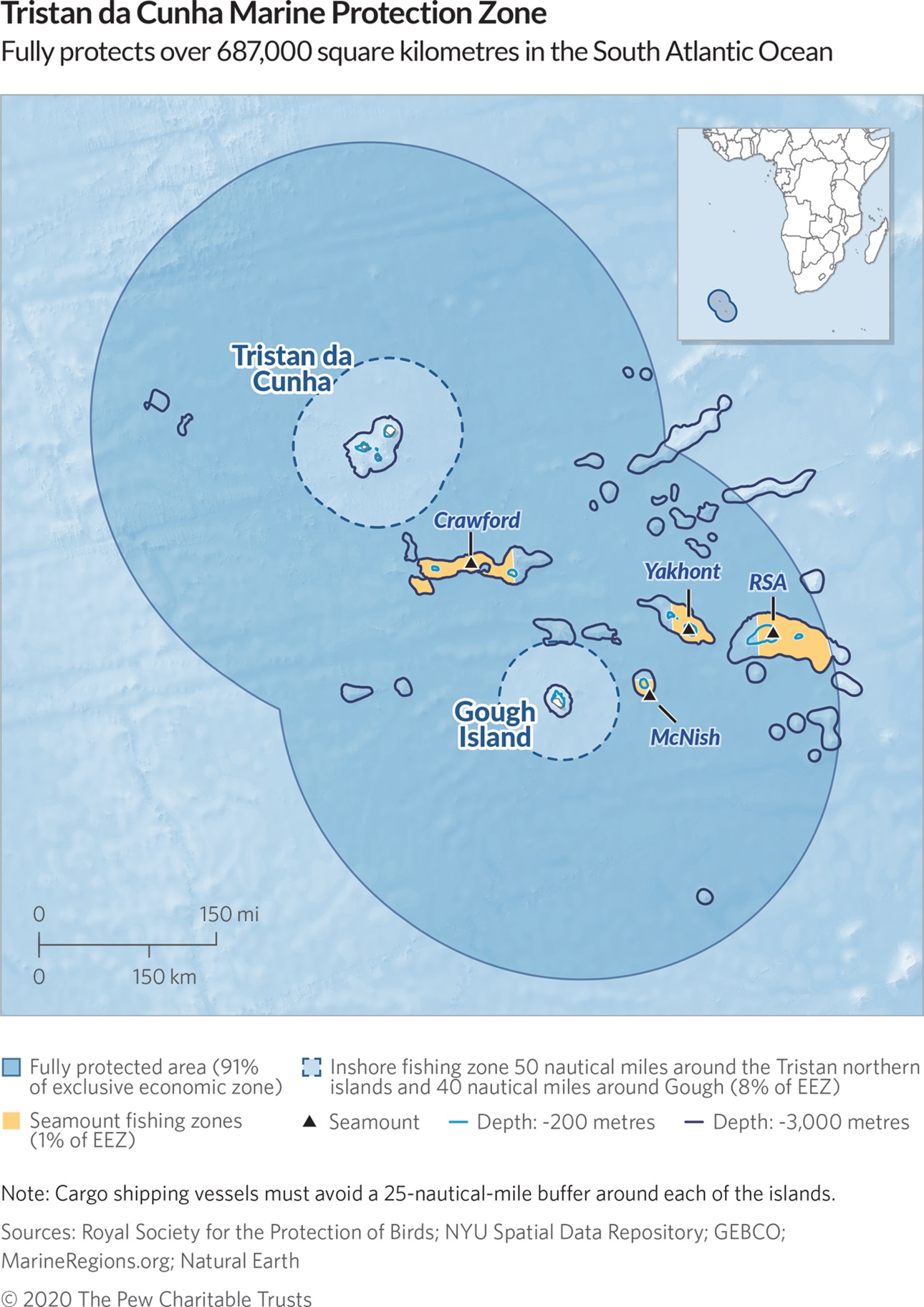

New Atlantic marine sanctuary will be one of world's largest

Photograph by Dan Myers, National Geographic Pristine Seas

From National Geographic by Sarah Gibbens

The waaters around one of the world’s most remote inhabited islands, in the middle of the South Atlantic Ocean, are set to become the fourth largest completely protected marine area in the world, and the largest in the Atlantic.

Today Government and people of #tristandacunha are proud to announce creation of the Tristan da Cunha Marine Protection Zone. Almost 700,00km2 will join UK #BlueBelt of marine protection, becoming the largest no-take zone in the Atlantic and the fourth largest on the planet. pic.twitter.com/3Dmn4ppEmd

— Tristan Admin (@fkilpatricktdc) November 13, 2020

📣With the announcement of Tristan da Cunha’s new Marine Protection Zone, the UK & Overseas Territories are now protecting 4.3 million sq km of the world’s ocean. 🇬🇧🌊🐋

— GREAT Britain (@GREATBritain) November 13, 2020

Join us in celebrating the incredible biodiversity protected by the @ukgovbluebelt👇▶️ #TogetherForOurPlanet pic.twitter.com/z7ywJkofjt

The Edinburgh of the Seven Seas

More to do

Links :