"computer-assisted grounding"

From Panbo by Ben Ellison

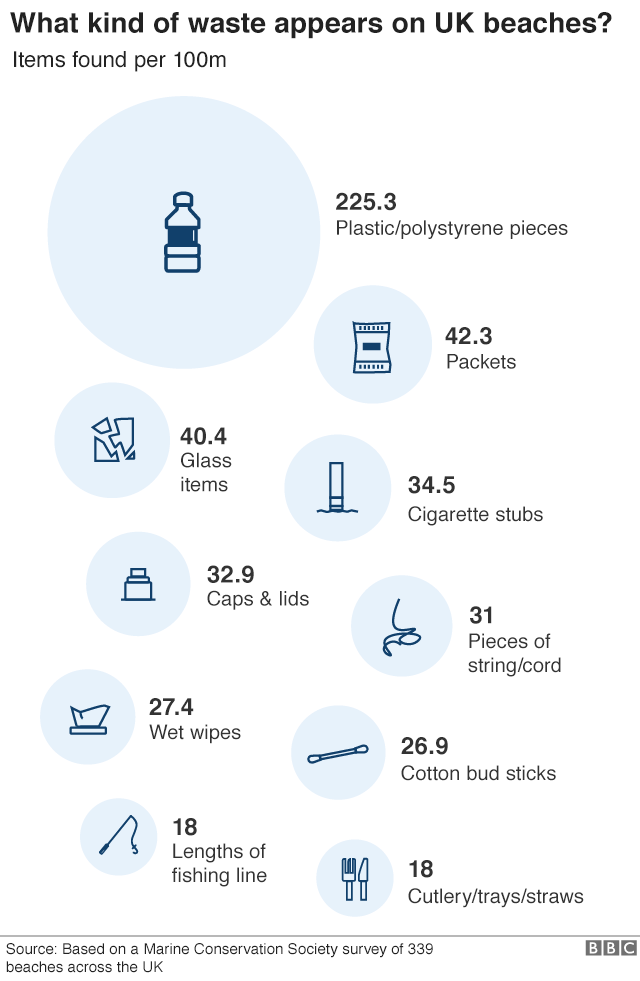

Despite incredible advances in chart availability and chart plotting, keels keep banging on reasonably well charted ledges and reefs all over the planet.

Why? I've made far too many navigation errors to play the righteous scold, but I am taken aback by the tendency of boaters to blame technology and especially the recent trend toward castigating chart manufacturers like Navionics as if perfect data is a possibility or even an entitlement...

The damaged keel photo above comes from a cruising blog entry titled

Navionics Sonar Charts & The Missing Reef, and my apologies in advance to Neil Langford for using his nicely written and illustrated accident analysis as a foil for my arguments about how we should be using electronic charts.

In fact, Neil seems like an especially good debate opponent as he and and his partner Ley are deeply experienced sailors -- 15 years and much of the globe in their wake -- who have also worked hard at sharing information with fellow cruisers.

Their site

S/V Crystal Blues is enjoyable and valuable reading, and I'm hoping they'll agree that our difference of opinion about their "computer-assisted grounding" is also educational.

Facts are not the issue.

The Navionics errors that Neil reports were 100% true -- I'm using the past tense because Navionics has already corrected them, thanks to Neil's input -- which I was able to verify myself using iPad charts that hadn't been updated yet.

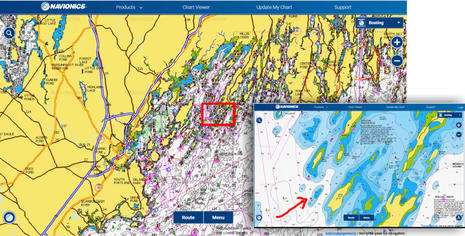

Bad Navionics charts?

The worst error in my opinion was that the regular Navionics chart (inset lower right above) did not show the 3-foot depth sounding clearly shown on the official NOAA raster chart at top, as well as the NOAA vector chart in the background above, even though Navionics bases its regular charts on the same NOAA data (like all the cartography manufacturers do).

But here's another fact: Every vector chart I've ever used, including NOAA's, sometimes misrepresents significant depth soundings that are prominently marked on the equivalent (paper-like) raster charts (that are largely drawn by human cartographers, not algorithms).

However, Neil's main complaint concerns Navionics SonarCharts, first how the 3-foot ledge was missing and then how many other errors he subsequently found, at least in comparison to official data.

Holy cow, as much as I appreciate SonarCharts, I've never even considered using them for primary navigation!

As discussed here, I love the ability to share depth information with other boaters, but I also regard SonarChart data with what seems like appropriate skepticism.

I expect to see more mistakes on non-official charts like this, and I don't expect perfection on any chart.

I was further surprised when Neil reported that fellow

Ocean Cruising Club members "were using the SonarCharts when navigating in harbors, as they valued the extra detail provided, and were shocked to hear of our collision."

Dang, the OCC is an experience-based club largely dedicated to sharing accurate up-to-date cruising information -- why I was proud to become a member -- but "extra detail" is not necessarily extra accurate, or even vaguely correct.

Isn't it obvious that

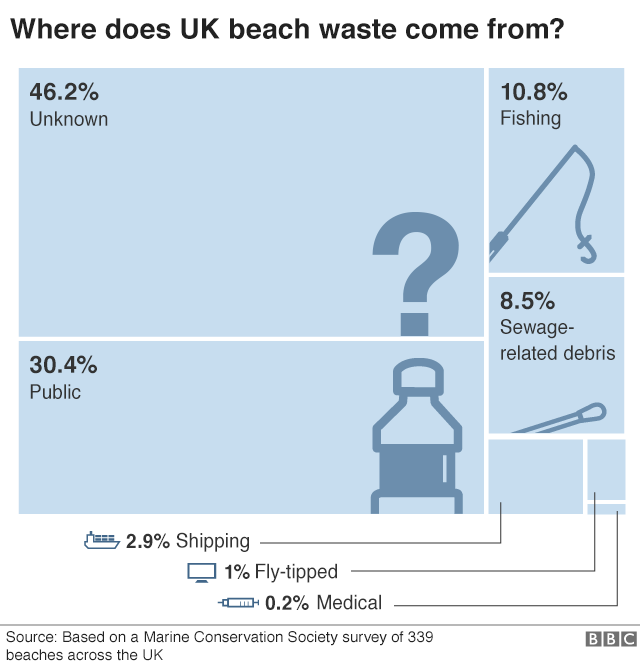

SonarCharts are based on depth data collected from boaters and other non-official sources, and thus best used alongside depth data at least originally vetted by hydrographic offices?

Apparently not, and Neil fairly points out how much Navionics brags about SonarChart detail in its marketing.

But then again, SonarCharts are always packaged along with regular Navionics charts, and the

Navionics Boating app he was using also offers a third "Government" chart choice in the U.S. (which did show the 3-foot sounding).

In the app you can flip from one chart type to another with a finger tap, and on a MFD you can window SonarCharts side by side with what Navionics sometimes calls their Nautical Charts.

Neil also points out that his Raymarine chartplotter prominently marks SonarCharts as "Not for Navigation," but then goes on to argue, "If I can't use them for navigation, what will I actually do with these SonarCharts?"

Well, sorry, but that's a sailor oblivious to the fact that a huge segment of chart users are fishermen who are very interested in bathymetry detail for finding spots where fish lurk, a use where data mistakes don't often lead to surprise keel groundings.

Perhaps ironically, excellent guidance on the

proper use of electronics charts can be found on the Navionics blog.

I recommend a thorough reading, but here are some key quotes with my boldfacing:

No single tool replaces the necessary use of sound judgement and proper seamanship.

Most boaters employ the good practice of consulting multiple chart sources and regularly updating cartography, while each has its benefits and limitations.

Proper understanding of an electronic chart is just as important as vessel maintenance and operation. In fact, reliance on electronic charts should never be done blindly since all charts have errors (official hydrographic office, government, private, or other).

The GPS available on boats is equivalent to the GPS on cars and light aircraft: meant to be used for visual orientation while driving, possibly with the aid of other instruments like sonar and radar, and cross checking every possible source of information.

The nautical chart, whether paper or electronic, is not designed and built for instrument navigation, but for orienting visual navigation.

The warnings that go with all charts are not there to protect the chart makers, but rather to protect the chart users from making mistakes in over-reliance on any one tool of navigation.

I like to think that many boaters already use "multiple chart sources," but how about the notion that charts are designed for "orienting visual navigation" instead of just the constant GPS plotting so many of us tend to use exclusively?

For me that's a new way of expressing a concept I've long held, and also a prinicipal that fits neatly into the history of charts.

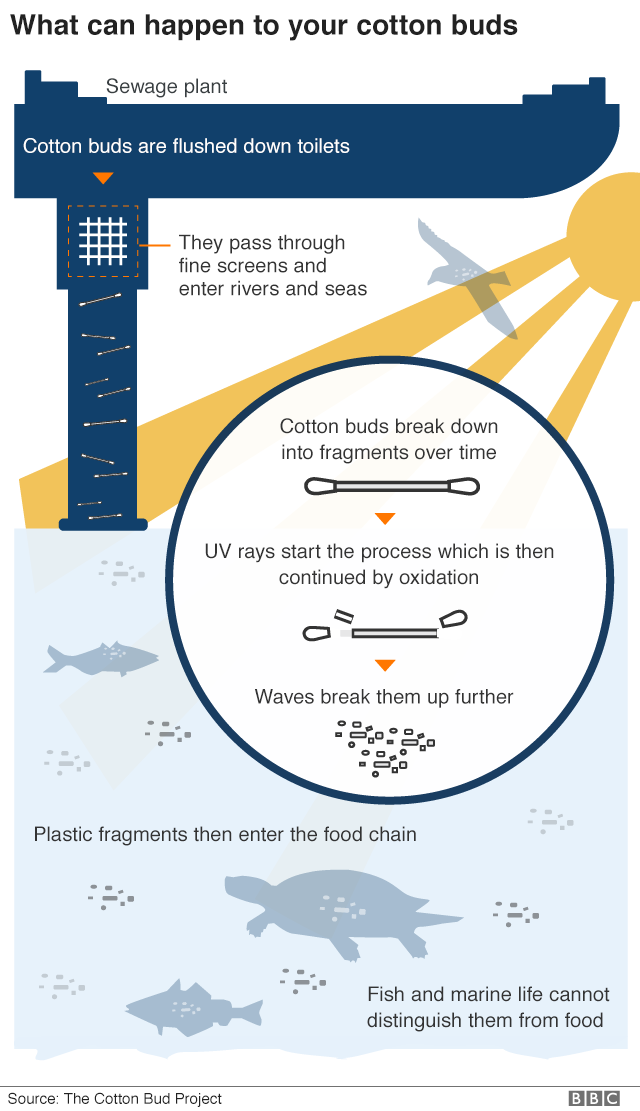

Ledge Chart & Nav History

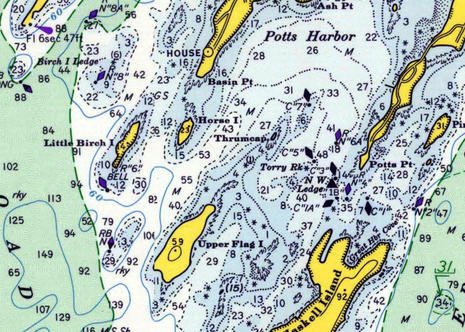

So let's take a look at the chart history of the Crystal Blues ledge, which lurks in the southwest passage to Potts Harbor in Casco Bay.

Again risking irony, the easiest way I know of to first get a good modern chart sense of the place is via this

link to Navionics' live and free Web chart.

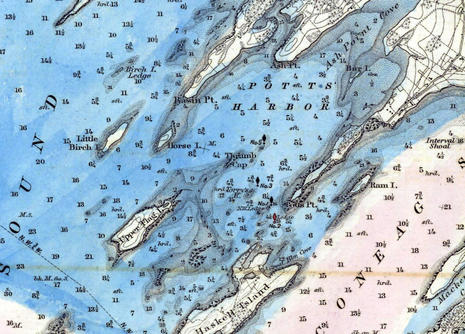

And here, thanks to

NOAA's Historical Chart Collection, is how Pott's Harbor was charted on paper in 1870 at 1:40,000 scale (

direct chart scan link here).

The ledge northwest of Upper Flag Island was already known and looks very close in position to modern charts, though the survey seems to have gotten the ledge's Mean Low Tide depth wrong at 6 feet instead of 3 (Maine ledges thankfully don't tend to grow).

But I suspect that most 1870 sailors tried to stay well clear of ledges they might not even bump in most conditions, and that was relatively easy to do in this case because the nearby islands provide lots of good visual guidancefor staying in deep water.

By the way, the soundings on this chart are in Feet for depths up to 18 feet and then in Fathoms, which may have been confusing.

Also, note that the blue coloring was not normal in 1870.

Instead, the particular chart scanned for NOAA's Collection was hand colored for a project about the typical extent of winter ice formation.

Unlike the ledges, winter saltwater ice in Maine has changed a lot.

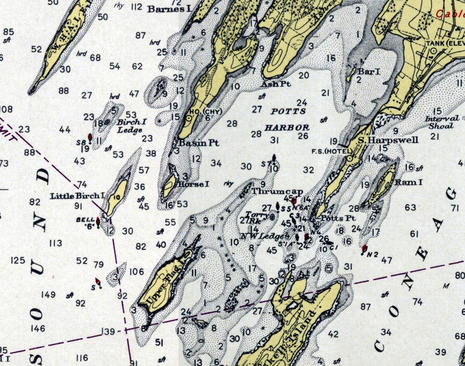

Now here's a snip from the same 1:40,000 Casco Bay chart as printed in 1943 (

direct link here).

All soundings are now in feet and the Crystal Bluesledge is not only surveyed as only 3 feet at Mean Low Water but also guarded on its west side by a red and black buoy.

If you check the Navionics web chart viewer or the

raster original via NOAA's online viewer, you'll see that red makes sense because the buoy is primarily a starboard hand mark for the main channel up Casco Bay.

And I presume that the secondary black marking was because the same nav aid could be used as a port hand mark for boats headed up to Pott's Harbor, though the USCG eventually changed their mind on that idea.

Besides the buoy as a visual aid, note how the cartographers included lots of onshore detail about further visual orientation.

And, incidentally, this 1943 chart cost 75 cents, same as it did in 1870, even though NOAA had added helpful red and yellow inks to the print process.

The chart makers had even more colors to work with on this 1971 Casco Bay chart (

direct link here), though the price had doubled to $1.50 (an ominous sign of

the $27 paper chart price to come).

The RB Nun had not been changed to RN "4" yet, but either way a navigator moving southwest out of Pott's Harbor was responsible for figuring out that the dangerous ledge lay between their boat and the nav aid.

Crystal Blues' navigator Neil Langford admits to inattention in that regard, but let's add an exclamation point!

Navigation aids are the visual marks -- by eye or radar, and sometimes audible, too -- that the USCG or similar authorities add to charted natural features as they find necessary for safe navigation. Consider the high cost of establishing and maintaining nav buoys, day beacons and so forth.

So isn't it folly for a navigator not to understand why each aid exists, what it's trying to warn you about?

The answers are often obvious, like marking a channel, but in complex topographies like the coast of Maine it can take some study.

And just because a GPS can accurately and constantly plot your position on a chart doesn't mean that you don't have to "read" the chart carefully.

Isn't that the grounding's lesson?

Modern charts

Casco Bay NOAA raster chart in the GeoGarage platform (Google Maps)

Casco Bay NOAA vector ENC chart in the GeoGarage platform (ArcGIS JS viewer & Bing Maps)

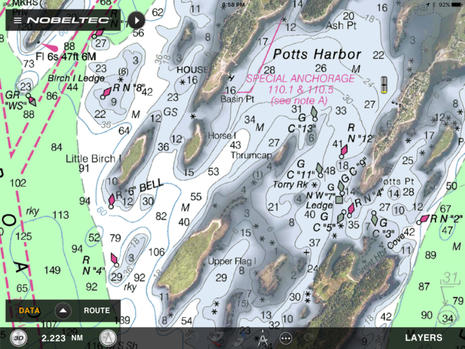

Now let's review various charts a boat like Crystal Blues could fairly easily have at hand on a tablet or dedicated marine display these days.

In U.S. waters, and many other places -- but with Navionics SonarCharts very much excepted -- almost all charts are based on the same official data.

The fundamental soundings, nav aids, shorelines, shore features, etc. come from the same source, and so the differences involve display nuances, timeliness, and added features.

For instance, I'm a big fan of TimeZero's ability to mix well rendered NOAA raster charts with their PhotoFusion high resolution satellite photos that often improve visual guidance regarding shore features and sometimes even shallow water and mooring detail.

Shown is a screen from the

TimeZero TZ app (the Nobeltec and MaxSea brand names are slowly going away), but very similar chart imaging, plus a vector choice, is available with TZ PC software and on various Furuno NavNet displays.

However, TimeZero chart data tends to be dated, at least in part because it's all reprocessed from the original sources so that it zooms, pans and even goes 3D quickly and smoothly.

For instance, if you search the

TimeZero Chart Catalog for current NOAA raster charts, you'll see a MWRUSAMAP10.1 Chart List PDF indicating that the last Revision Dates of the current batch are in late 2016 at best.

The raster chart dates for other areas like the Caribbean are often even older, sometimes much older (and the 11.1 date list for TZ NOAA vectors doesn't look good either).

But then again,

the TimeZero app with all NOAA raster charts or a big area of Europe costs about $50, the equivalent of about two current NOAA print-on-demand paper charts.

And the TZ vector charts sourced from C-Map that can be purchased for other TZ and Furuno charting engines all seem to have been refreshed last summer.

Also, to my knowledge, only Navionics claims to be constantly updating the charts they make available for download, and Navionics is about the worst at documenting the sources and dates of the specific data sets behind their charts.

For more detail about data sourcing mysteries, please see

my 2016 review of Cuba charts, and also note that no chart maker I know of is yet doing much with

NOAA's valuable Zones of Confidence (ZOC) initiative.

The bottom line: Digital charts are relatively inexpensive, but it's a good idea to have more than one set.

Here's the Pott's Harbor area as seen on a Garmin BlueChart, and I used the inset to show how I had to zoom in deeper before the 3.0 foot sounding that surprised Crystal Blues came on screen.

That's not particularly peculiar to BlueCharts and, as noted earlier, it's not uncommon in my experience for the algorithms that determine vector chart display to miss an important sounding altogether.

On the other hand, Garmin's bold shallow watercolors are a good visual hint at possible issues.

Note that I took this screen in September (when I started this entry), and now the BlueChart Mobile (BCM) app I used has been sadly discontinued.

But then again, if you own a Garmin chart plotter made since 2012, the

new ActiveCaptain app I reviewed can put its charts on your tablet or phone at no further cost.

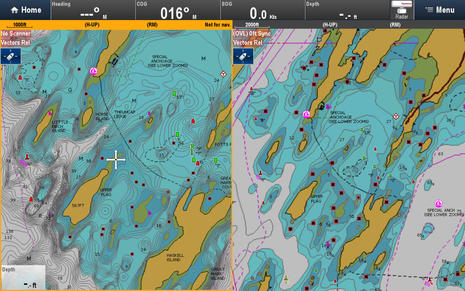

This is how I think Navionics SonarCharts should be used, side by side with the company's regular navigation charts.

So the underwater detail you see on the right is based on (NOAA's) official hydrographic office data -- though vintage and ZOC unknown -- while the "extra detail" on left is derived from crowdsourced sonar logs and other sources completely unspecified but definitely not official.

These charts are on a

Navionics+ card that can be updated at any time during the first year of ownership and thereafter, if you renew your subscription. And the card is being displayed on a Raymarine eS Series MFD, though it will also work with MFDs made by Navico and others (maybe why it seems strange that Garmin now owns Navionics).

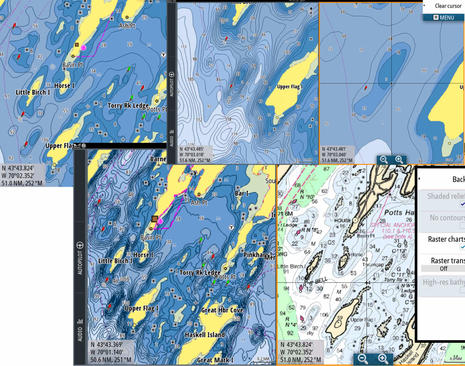

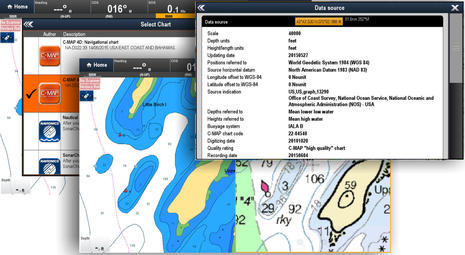

C-Map can offer even more chart types on a single card than Navionics.

Their 4D Max+ bundle -- seen on a Simrad NNS evo2 above, but also available for Raymarine MFDs -- includes a raster chart layer sourced from hydro offices around the world as well as familiar C-Map vector charts, and C-Map "High Resolution Bathy Data" looks a lot like Navionics SonarCharts, though again source unknown plus no crowdsourced data added (yet).

But now that C-Map is a corporate sibling to Navico, the Genesis crowdsourcing technology has become C-Map Genesis, which may well become part of future C-Map cartography bundles.

Perhaps also telling about the future of C-Map -- which has just become the main chart choice besides Garmin/Navionics -- is that they just acquired i-Sea, which has already developed Embark apps that seem to take a very modern approach to route and information sharing.

Maybe we'll see new C-Map apps with the advanced features I recently highlighted in Navionics Boating plus an able alternative to the ActiveCaptain crowdsourcing now also owned by Garmin?

Here's what C-Map 4D Max+ looks like on the Raymarine eS128 running Lighthouse 2, and it's interesting to note that the new Lighthouse 3 currently running only on Axiom Series displays also learned to display C-Map recently.

With Raymarine now the only major brand that doesn't own its own chartmaking operation -- TimeZero for Furuno uses some base data from other companies, but not their advanced features -- one speculation is that C-Map and Garmin/Navionics will compete for their business.

So that great screen of chart choices in the background above may be the future.

Note, too, the source detail that C-Map has long been good about.

And that overall it's pretty easy to have multiple chart choices on your boat right now.

Chart-assisted law suit?

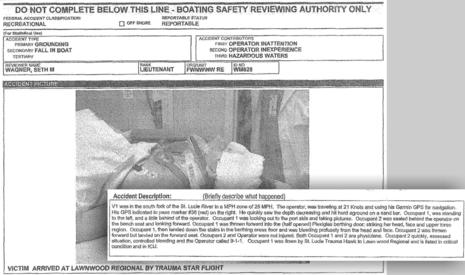

Finally, while I've probably spent too much time giving Crystal Blues a hard time about blaming Navionics SonarCharts for not providing a level of perfection that should not be expected, the misuse of charts can have much graver consequences than a damaged keel.

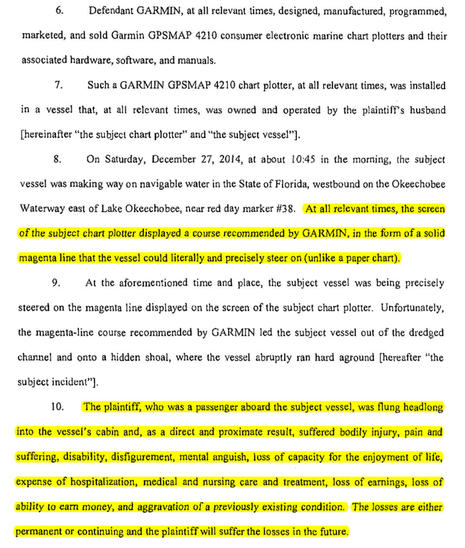

The litigation you can read about in

Peter Swanson's Wreck on the Magenta Line illustrates the serious injury possible and also how chartmakers may be financially inhibited from doing things many of us would like them to do, like trying to improve official chart data with other sources, us included.

I don't think the case has been settled yet, but having looked at some public court records and some relevant chart history, it looks to me like Garmin was helping boaters by putting the magenta line on what seemed like the wrong side of a marker.

Navionics did the same thing, and ActiveCaptain had user reports about the shoaling where the channel was supposed to be, all of which was happening in place that NOAA only charts at a fairly useless 1:80,000 scale.

Besides, even if the Magenta Line says so, going fast on the wrong side of a nav aid seems like over reliance on chartplotting to me.

Wasn't it inattention and poor navigation practices that assisted this grounding, not a chart plotter?

But the lawyers may be persuasive the other way, and here we are with evidence that even very experienced navigators can apparently be lulled by the precise look of GPS on an electronic chart. Do we have a real problem here, and if so, what's the remedy?

Links :