From AMTI by Eleanor Freund (pdf report)

From AMTI by Eleanor Freund (pdf report)

Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) are one of the principal tools by which the United States challenges maritime claims deemed excessive under international law.

Although the U.S. Navy has conducted FONOPs all over the world for nearly 40 years, recent operations began garnering unprecedented publicity as a point of friction with China in the contentious South China Sea disputes.

Since October 2015, the United States has conducted seven FONOPs that seek to challenge specific Chinese claims in the area.

Eleanor Freund of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs recently

published a report on the FONOPs program that details exactly how the U.S.Navy challenged five of those seven claims (the report went to print before the most recent two operations), as well as explaining the purpose and utility of the program in the South China Sea.

AMTI has reproduced Freund’s charts illustrating each of the operations in chronological order, below.

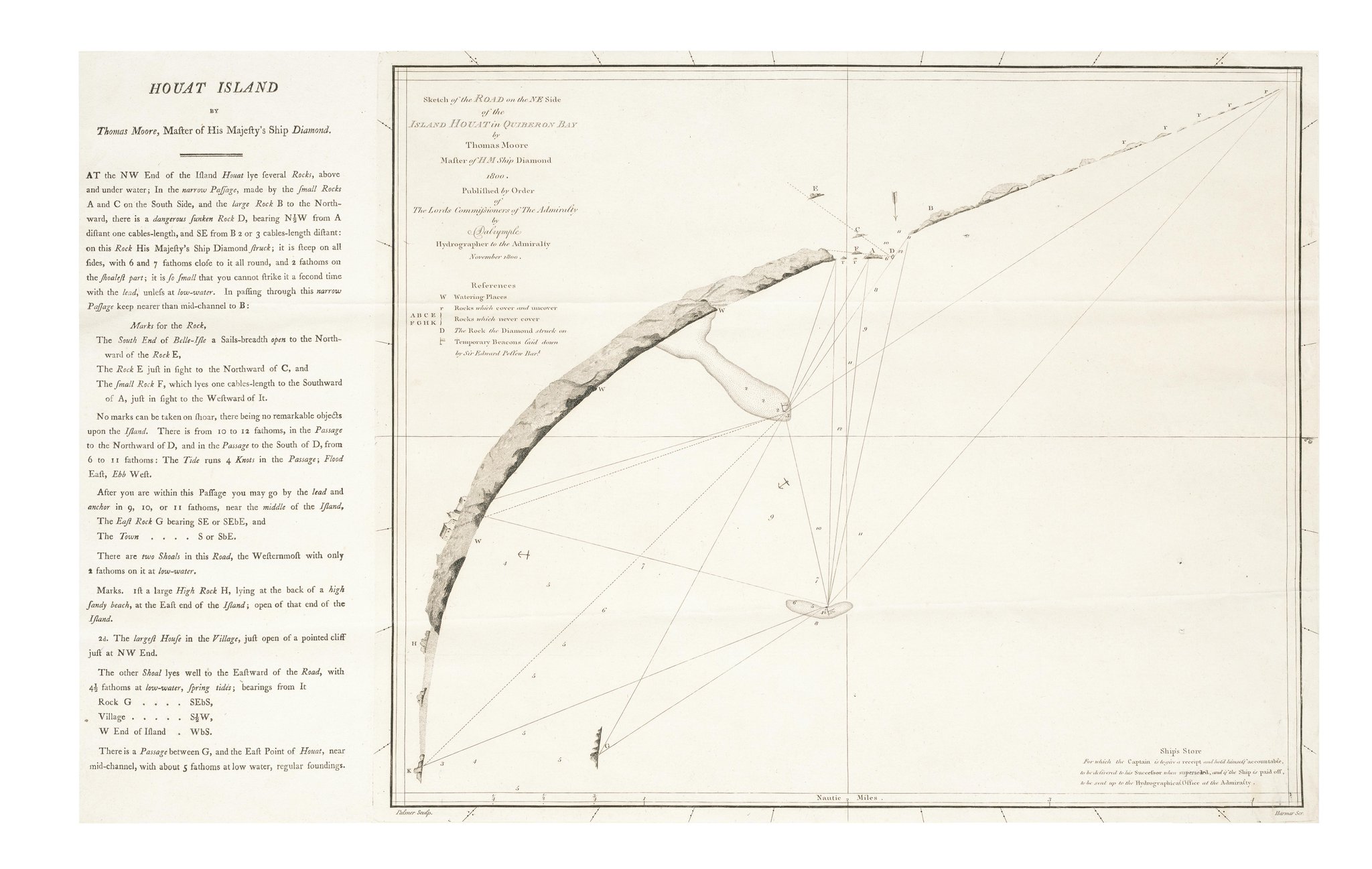

U.S. Freedom of Navigation Operation #1

Date: October 27, 2015

Location: Spratly Islands (Subi Reef, Northeast Cay, Southwest Cay, South Reef, Sandy Cay)

Vessel: USS Lassen (DDG-82)

Excessive Maritime Claim: Requirement that states provide notice/obtain permission prior to innocent passage through territorial sea

Nature of Transit: Innocent passage

On October 27, 2015, the U.S. Navy destroyer USS Lassen conducted a freedom of navigation operation by transiting under innocent passage within 12 nautical miles of five features in the Spratly Islands—Subi Reef, Northeast Cay, Southwest Cay, South Reef, and Sandy Cay—each of which is claimed by China, Taiwan, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

The freedom of navigation operation was designed to challenge policies by China, Taiwan, and Vietnam requiring prior permission or notification of transit under innocent passage in their territorial sea.

Accordingly, the United States did not provide notification, or request permission, in advance of transiting under innocent passage.

It should be noted, however, that none of these states has formally made a legal claim to a territorial sea around these features.

Indeed, no state has made any specific claims to the waters surrounding the features it occupies in the Spratly Islands.

In practice, however, they still require that states obtain permission or provide notice prior to transiting within 12 nautical miles, and these specific features would be legally entitled to a territorial sea.

As a result, the United States observed requirements of innocent passage during its transit.

The United States does not take a position on which nation has sovereignty over each feature in the Spratly Islands, and the operation was not intended to challenge any country’s claims of sovereignty over land features.

U.S. Freedom of Navigation Operation #2

Date: January 29, 2016

Location: Paracel Islands (Triton Island)

Vessel: USS Curtis Wilbur (DDG-54)

Excessive Maritime Claim: Requirement that states provide notice/obtain permission prior to innocent passage through territorial sea

Nature of Transit: Innocent passage

On January 29, 2016, the U.S. Navy destroyer USS Curtis Wilbur conducted a freedom of navigation operation by transiting under innocent passage within 12 nautical miles of Triton Island in the Paracel Islands.

Triton Island is occupied by the Chinese, but also claimed by Taiwan and Vietnam.

The island is legally entitled to a territorial sea.

The freedom of navigation operation was designed to challenge policies by China, Taiwan, and Vietnam requiring prior permission or notification of transit under innocent passage in the territorial sea.

Accordingly, the United States did not provide notification, or request permission, in advance of transiting under innocent passage.

The United States does not take a position on which nation has sovereignty over each feature in the Spratly Islands, and the operation was not intended to challenge any country’s claims of sovereignty over land features.

U.S. Freedom of Navigation Operation #3

Date: May 10, 2016

Location: Spratly Islands (Fiery Cross Reef)

Vessel: USS William P. Lawrence (DDG-110)

Excessive Maritime Claim: Requirement that states provide notice/obtain permission prior to innocent passage through territorial sea

Nature of Transit: Innocent passage

On May 10, 2016, the U.S. Navy destroyer USS William P. Lawrence conducted a freedom of navigation operation by transiting under innocent passage within 12 nautical miles of Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratly Islands.

Fiery Cross Reef is occupied by the Chinese, but also claimed by the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam.

At the time that the freedom of navigation operation was conducted, it was unclear if Fiery Cross Reef was legally considered a rock or an island.

Moreover, none of the claimant states has formally made a legal claim to a territorial sea surrounding Fiery Cross Reef.

Nevertheless, because Fiery Cross Reef is legally entitled to a territorial sea, irrespective of whether it is a rock or island, the United States transited within 12 nautical miles of Fiery Cross Reef under the provisions of innocent passage.

When the decision in the Philippines v. China case was issued in July 2016, Fiery Cross Reef was found to be a rock.

7

As in the previous two examples, this freedom of navigation operation was designed to challenge policies by China, Taiwan, and Vietnam requiring prior permission or notification of transit under innocent passage in the territorial sea.

Accordingly, the United States did not provide notification, or request permission, in advance of transiting under innocent passage.

The United States does not take a position on which nation has sovereignty over each feature in the Spratly Islands, and the operation was not intended to challenge any country’s claims of sovereignty over land features.

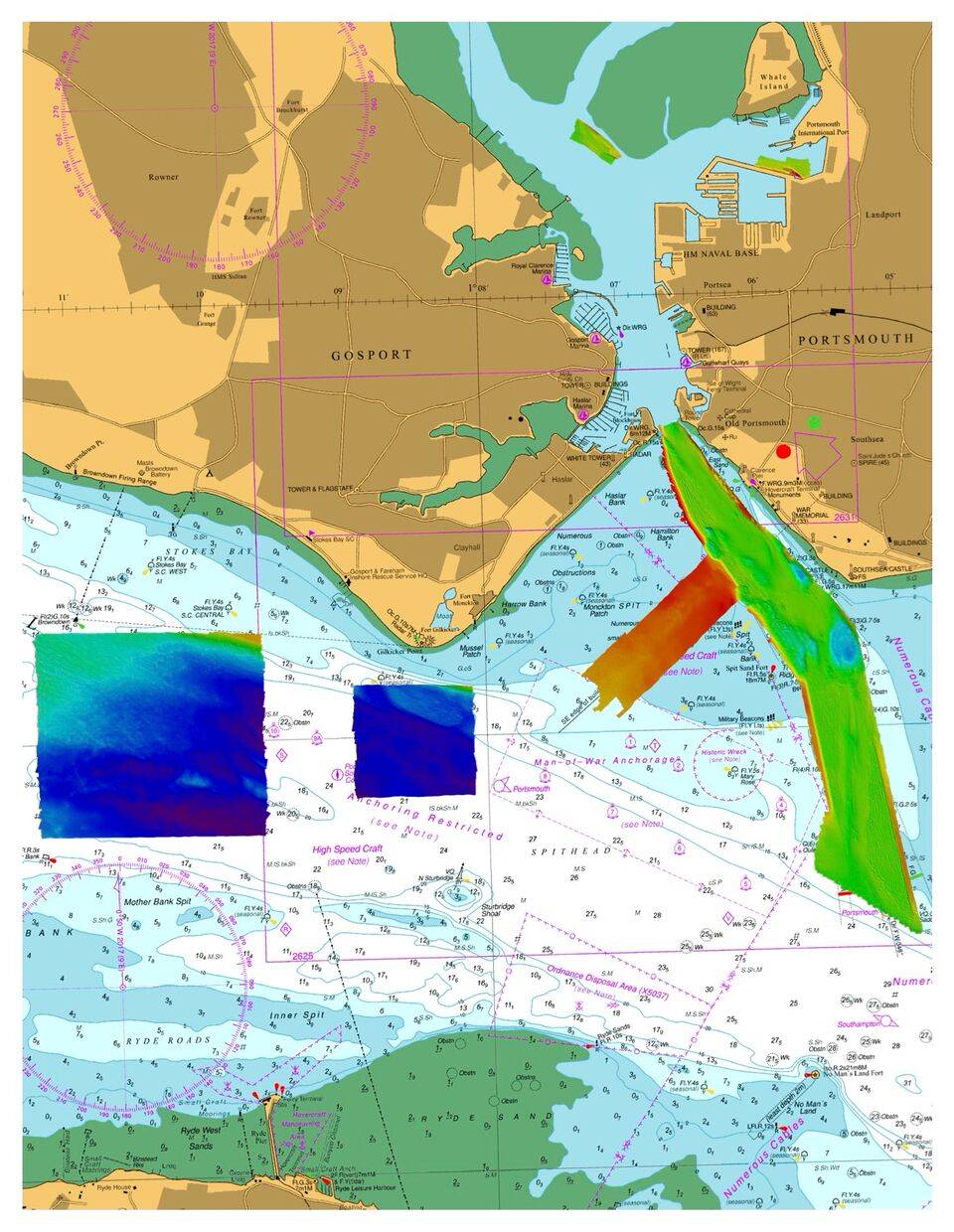

U.S. Freedom of Navigation Operation #4

Date: October 21, 2016

Location: Paracel Islands

Vessel: USS Decatur (DDG-73)

Excessive Maritime Claim: Excessive straight baseline claims

Nature of Transit: Sailing on the high seas

The fourth freedom of navigation operation, conducted on October 21, 2016, differed from the three previous freedom of navigation operations in that it did not challenge the illegal requirement that states provide notification or obtain permission prior to transiting through another state’s territorial sea under innocent passage.

Rather, it challenged excessive straight baseline claims made by China around the Paracel Islands.

The Paracel Islands are occupied by the Chinese, but also claimed by Taiwan and Vietnam.

Baselines are the point from which the territorial sea, contiguous zone, and exclusive economic zone are measured.

Generally speaking, they exist at the low-water line along the coast.

On May 15, 1996, China issued a statement establishing straight baselines around the Paracel Islands in the South China Sea.

The purported straight baselines, drawn between 28 basepoints, enclose the Paracel Islands in their entirety.

Straight baselines are important because—where they are established legally—they become the point from which a state can measure the breadth of its territorial sea, the contiguous zone, and other claimed maritime zones.

By drawing straight baselines around the Paracel Islands, China claimed the entire enclosed area as part of its sovereign waters as well as a 12 nautical mile territorial sea surrounding the enclosed area.

The United States does not recognize China’s straight baselines claim around the Paracel Islands for the reason that UNCLOS allows only archipelagic states (i.e. countries comprised entirely of islands) to draw straight baselines around island groups.

China, as a continental state, cannot claim such a right.

On October 21, 2016, the U.S. Navy destroyer USS Decatur conducted a freedom of navigation operation by crossing China’s claimed straight baselines in the Paracel Islands, loitering in the area, and conducting maneuvering drills.

The USS Decatur did not approach within 12 nautical miles of any individual land feature entitled to a territorial sea; rather, it sailed in the area between the outer limits of the 12 nautical mile territorial seas and China’s claimed straight baselines.

In doing so, the USS Decatur crossed into waters that would be considered China’s internal waters if its straight baseline claims were legal, which they are not.

(Internal waters are accorded the rights of the territorial sea.)

Because the USS Decatur loitered and conducted maneuvering drills, which cannot be considered continuous and expeditious passage, it signaled that it was not transiting under innocent passage and did not consider the waters to be part of the territorial sea.

(Remember, innocent passage requires continuous and expeditious transit through another state’s territorial waters. See pages 12–14 and 19–20 for further elaboration on this point.)

In doing so, it deliberately challenged China’s claim of straight baselines around the Paracel Islands.

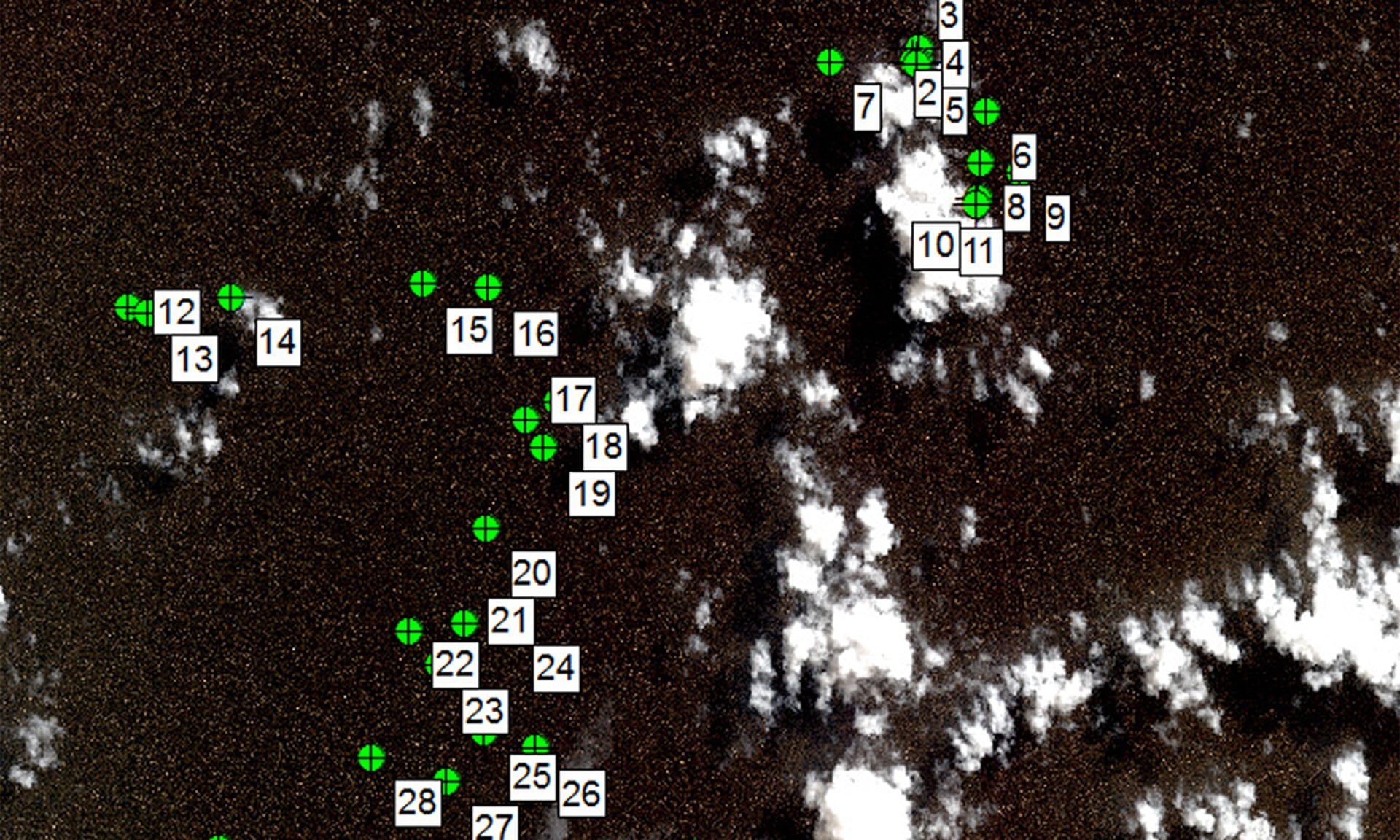

U.S. Freedom of Navigation Operation #5

Date: May 24, 2017

Location: Spratly Islands (Mischief Reef)

Vessel: USS Dewey (DDG-105)

Excessive Maritime Claim: Unclear, presumed illegal territorial sea

Nature of Transit: Sailing on the high seas

On May 24, 2017, the U.S. Navy destroyer USS Dewey conducted a freedom of navigation operation by transiting within 12 nautical miles of Mischief Reef in the Spratly Islands.

Mischief Reef is occupied by the Chinese, but also claimed by the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam.

When the Permanent Court of Arbitration issued the decision in Philippines v. China, it found Mischief Reef to be a low-tide elevation.

For that reason, Mischief Reef is not legally entitled to a territorial sea.

The USS Dewey navigated within 12 nautical miles of Mischief Reef and proceeded to sail in a zigzag pattern.

It also conducted a “man overboard” drill.

Both actions were clear indications that the USS Dewey did not intend to transit under innocent passage.

(Remember, innocent passage requires continuous and expeditious transit through another state’s territorial waters. Sailing in a zigzag pattern and conducting a man overboard drill are both violations of this condition. See pages 12–14 and 19–20 for further elaboration on this point.)

Presumably then, the freedom of navigation operation was intended to challenge the existence of an illegal territorial sea around Mischief Reef by sailing within 12 nautical miles of the feature in a manner not in accordance with innocent passage.

Complicating the operation, however, is the fact that neither China, the Philippines, Taiwan, nor Vietnam has actually claimed a territorial sea around Mischief Reef.

This raises the question: what excessive maritime claim was the United States actually challenging? If the United States was not disputing an existing excessive maritime claim, then its actions would be more accurately described as sailing on the high seas than as a freedom of navigation operation.

Unfortunately, the Pentagon has not explained the legal rationale behind the operation so the intent of the USS Dewey’s operation remains unclear.

As was true in prior examples, the United States does not take a position on which nation has sovereignty over each feature in the Spratly Islands, and the operation was not intended to challenge any country’s claims of sovereignty over land features.

Links :