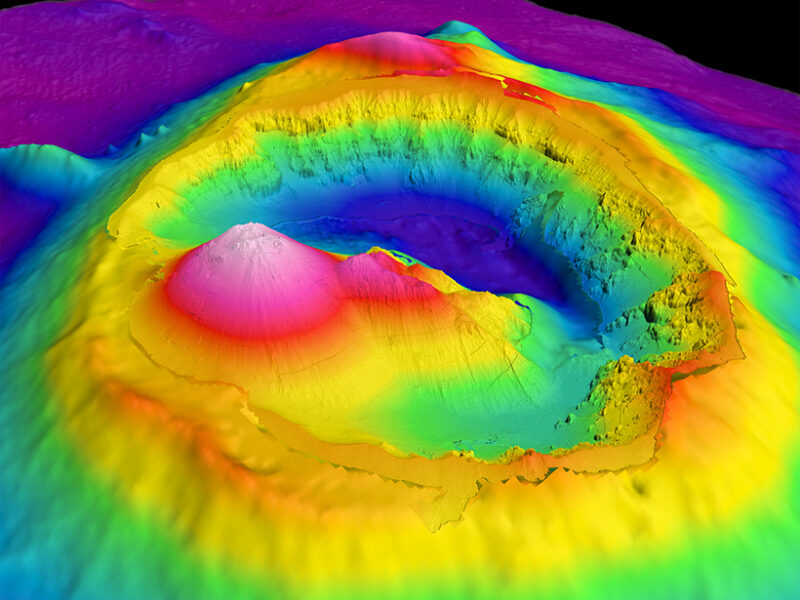

Bathymetry image of Brothers Seamount and caldera, an undersea volcano

about 3 kilometers in diameter off the coast of New Zealand.

Autonomous

underwater vehicles acquired high-resolution (2-meter) bathymetry data

inside the caldera.

Surface ships mapped the lower-resolution (25- to

30-meter) bathymetry data on the surrounding volcano flanks.

This

feature was formally named using tools provided by the General

Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO).

Credit: S. Merle (NOAA/PMEL)

From EOS by By

The Izu-Ogasawara Trench, a deep-sea trench south of Japan, was discovered in 1933 and named after the nearby Ogasawara Islands.

However, the Ogasawara Islands have also been called the Bonin Islands: They are the type locality for the volcanic rock boninite [Crawford, 1989].

Consequently, the Izu-Ogasawara Trench is often incorrectly and confusingly referred to as the “Izu-Bonin Trench.”

Newly discovered undersea features are often given informal names that over a period of years, with repeated use, become incorporated into maps and scientific papers.

Historically, this has sometimes led to confusion and misidentification.

Occasionally, one name has been used for several different features, or a single feature has been named independently by different groups, resulting in several different informal names.

One might think that with the rise of global communications and data-sharing networks, this problem might resolve itself.

However, new ocean exploration technologies are exacerbating this old problem by adding to the inflow of new information.

An increasing number of ships now routinely survey our oceans, and we are learning more about the seafloor and its features.

The rapid developments in multibeam sonar technology and the deployment of these instruments on remotely operated vehicles (ROV) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV) mean that some features only tens of meters in relief are now being mapped and named.

To ensure that these features’ names don’t get renamed on subsequent cruises, scientists turn to a reliable tool: the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO) Gazetteer online interactive map.

This map is supplemented with other online resources, including naming guidelines, links to proposal forms, and a glossary.

GEBCO’s Sub-Committee on Undersea Feature Names (SCUFN) is also developing new Web applications to facilitate collaboration and coordination for naming undersea features within the world’s oceans.

These future applications, plus the new Web supplemental resources, will assist users in completing name proposals and should help speed up the review and approval process.

Louisville seamounts

The GEBCO Gazetteer

GEBCO, an international group of experts in ocean surveying and mapping, established SCUFN in 1975 when the need became apparent for a uniform policy for the handling and standardization of undersea feature names.

GEBCO’s aim is to provide the most authoritative publicly available bathymetry of the world’s oceans, including undersea feature names.SCUFN reviews name proposals for undersea features that lie entirely or mainly (more than 50%) outside the external limits of territorial waters.

The subcommittee comprises a multinational group of hydrographers and Earth scientists. SCUFN is supported by a secretariat based at the International Hydrographic Organization in Monaco, which coordinates its activities and maintains the GEBCO Undersea Feature Names Gazetteer.

This gazetteer contains a list of more than 3800 named features throughout the oceans.

Several national naming authorities and geographic naming boards also maintain separate gazetteers that include names of undersea features outside territorial waters, and SCUFN endeavors to harmonize the GEBCO Gazetteer with these names.

The gazetteer enables users to search and view features quickly.

It also provides further metainformation (where it is available) about feature dimensions, the discoverer, and the origin of the name.

Proposers of new undersea feature names or journal reviewers can use this resource to ensure that names are not duplicated or features are not already named.

This image shows over 14,000 large seamounts identified from a mid-resolution bathymetric map, using methods outlined in Kitchingman and Lai (2005).

There are more small seamounts, but their distribution should be roughly similar to that shown here.

Proposing Undersea Feature Names

People who want to propose names for new features should use the GEBCO undersea feature names website.

This site describes the role of SCUFN and has useful links to proposal forms, naming guidelines, and meeting reports.

The SCUFN guidelines for naming features are given in the “Standardization of Undersea Feature Names,” International Hydrographic Organization Publication B-6, which is available in six languages.

This publication includes information about proposals along with examples of supporting documentation, including maps and images depicting the features.

Undersea feature names have two parts: a specific term and a generic term.

The specific term should primarily relate to nearby onshore or offshore features, the discovery ship, or an eminent maritime figure, explorer, or scientific researcher.

Other specific terms may be given to recognize cultural icons or traditions.

The generic term relates to the geometrical form of the feature (escarpment, seamount, trench, etc.) or, in special cases, the genesis of the feature. SCUFN regularly reviews generic terms, adding new terms as they become established in scientific usage and abandoning older terms that have fallen out of use.

For example, the Adare Trough, located in the Ross Sea off the coast of Oates Land, Antarctica, is a flat-bottomed depression with symmetrical, parallel sides that is more than 100 kilometers long.

The specific term “Adare” is from the nearby Cape Adare, and the generic term “trough” describes the morphology of the feature.

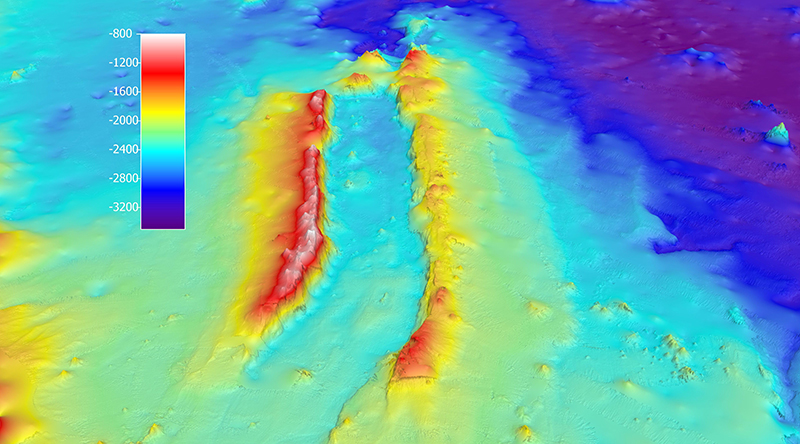

The Adare Trough, located in the Ross Sea off the coast of Oates Land,

Antarctica, has the specific name “Adare” that refers to the nearby Cape

Adare and the generic name “trough” that describes the morphology of

the feature.

The color scale gives the elevation in meters.

Credit: GNS

Science

Several features in the GEBCO gazetteer have generic terms that are no longer recommended but are maintained to harmonize names with other gazetteers.

Definitions for generic terms, including example images of feature types, are now readily available on a new website.

This resource allows those proposing new undersea feature names to identify the correct generic term for the features they find.

Currently, proposals are emailed directly to the SCUFN secretariat (info@iho.int), where they are uploaded onto a Web application and shared with subcommittee members for review.

Final approval of proposed names is made at the annual SCUFN plenary meeting.

SCUFN members consider proposals in the chronological order of submission: Late proposals will be considered last if there is sufficient time at the plenary meeting.

For each of the past 5 years, SCUFN has reviewed between 70 and 200 names.

In 2016, the subcommittee reviewed 206 feature names, and 144 of these will be added to the GEBCO Gazetteer.

Mapping, Classifying, and Protecting Seamounts (GRID Arendal)

What are seamounts?

How are they mapped?

How are they classified?

How can we use these spatial data to protect marine environments?

These are some of the questions highlighted in this story map.

What are seamounts?

How are they mapped?

How are they classified?

How can we use these spatial data to protect marine environments?

These are some of the questions highlighted in this story map.

Future Goals

We plan to enable users to submit undersea feature name proposals to SCUFN via a new Web application using an online form or by uploading a completed proposal document with accompanying images.

SCUFN members can then immediately access these submissions to assess feature names and share comments about each proposal.

In this way, the new interface will help speed up SCUFN review and approval processes.

We expect to unveil this new Web tool in 2017.

The online submission tool will include a facility for submitting geographic information system files (GIS shapefiles) that can be used to help evaluate the proposal and can be incorporated into the Web map application.

Until that tool launches, we encourage users of undersea feature names in scientific literature and on bathymetric maps to access the current iteration of the gazetteer as well as resources connecting them to generic feature terms and naming guidelines.

Once proposals become more streamlined, we will be well positioned to meet our goal: to increase the number of feature names in the GEBCO Gazetteer and to make them readily available to the scientific community for publications and Web map services.

Links :

- Seamounts online

- Seamount catalog

- GeoGarage blog : Life thriving on UK's biggest underwater mountains / The deep ocean: plunging to new depths to discover the ... / Seamount discovery / Scripps mapping subsea mountains taller than Mt. Whitney / Christmas Island seamounts: is the mystery finally solved? / Seamounts identified as significant, unexplored territory

No comments:

Post a Comment