From The Economist

BOLIVIA has a navy. Merchant vessels sail the high seas under the Bolivian flag.

The country celebrates March 23rd as the “Day of the Sea”.

In fact, Bolivia has all the trappings of a maritime power except an actual coastline (confining its navy to lakes and rivers).

It lost its littoral to Chile in a 19th-century war and has been trying to recover a piece of it almost ever since.

On May 4th Bolivia’s quest entered a new phase when the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague began hearings on its demand for Chile to grant it “sovereign access to the sea”, ie, territory that would reconnect it to the Pacific Ocean.

The government commissioned 35 musicians to record a song, “Beaches of the Future”, to drum up international support.

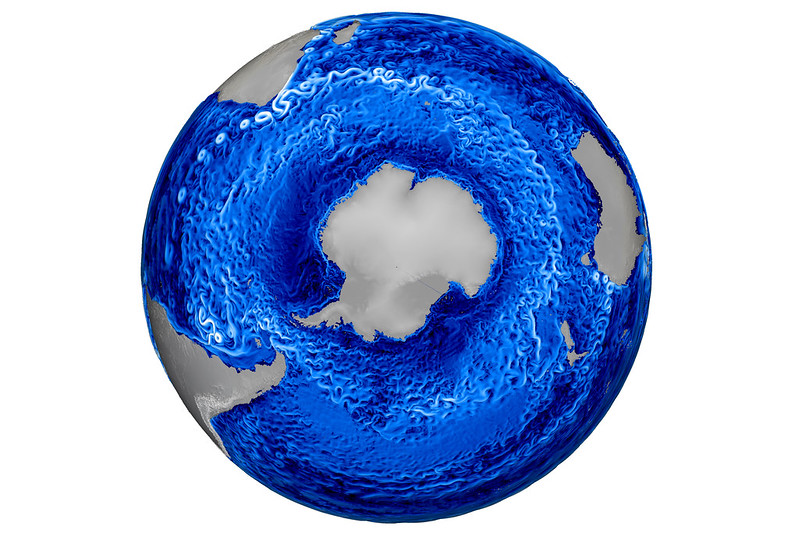

Bolivia's territorial losses (1867–1938)

It faces long odds.

The first hearings address Chile’s objection to the whole procedure on the grounds that the court has no jurisdiction in the matter.

Only if the ICJ rejects Chile’s position, or defers a decision, will it consider Bolivia’s claim that Chile has an “obligation to negotiate” access to the sea.

That, Chile will argue, is a dangerous notion.

It would overturn the treaty that ended hostilities between the two countries, and thus pose a threat to the system of treaties that undergirds much international law.

If that is right, more is at stake in the Dutch courtroom than Bolivia’s hankering for beachfront property.

The struggle has its origin in the exploitation of nitrates, used for fertiliser and to make saltpetre for the manufacture of gunpowder, in the Bolivian littoral, whose sparse population was mainly Chilean.

Angered by an increase in Bolivian tax on nitrate miners, Chile invaded the port of Antofagasta in 1879.

By the end of the four-year war it had also defeated Peru, which had allied with Bolivia, annexing its departments of Arica and Tacna (see map).

In all, Bolivia lost 400km (250 miles) of coastline and 120,000 square km of territory.

Peace was concluded only with a “treaty of peace and friendship” in 1904, under which Bolivia accepted the loss of its Pacific coast.

In return Chile promised Bolivia “the fullest and freest” commercial transit.

Bolivia is not reconciled to the loss.

The poorest country in South America, it blames its plight largely on its landlocked condition (see article).

Much of Chile’s hoard of copper, its main export, lies underneath what was Bolivian soil.

The commitment to free transit “is not as wonderful as Chile likes to portray,” says Eduardo Rodríguez Veltzé, a former Bolivian president who is now ambassador to the Netherlands.

Although Bolivia has its own customs officials and storage in Arica and Antofagasta, it complains that Chile has created an obstacle course for exporters.

It subjects Bolivian cargo to unwarranted inspections, for example.

Bolivia’s constitution, enacted in 2009 under the current president, Evo Morales, calls access to the Pacific an “irrevocable right”.

That frustrated ambition has made for a relationship with Chile that is at once prickly and intimate.

The two countries’ citizens can cross the border without passports, and most Bolivian goods have duty-free access to Chile’s market.

Despite the obstacles, two-thirds of Bolivia’s long-distance trade passes through Chilean ports.

Yet liberal, outward-looking Chile has little rapport with the left-wing nationalists who currently govern Bolivia.

Commerce lags behind its potential.

Chilean companies, avid investors in neighbouring countries, have risked hardly any money in Bolivia.

In turn, Bolivia has spurned big opportunities merely to spite Chile.

A president who wanted to export gas through Chilean ports was forced out of office in 2003. In a referendum the following year, voters said Bolivia should use gas as a negotiating tool to gain access to the Pacific.

With the suit at the ICJ, Bolivia is trying a new tack.

It insists that this is not an attempt to reopen the 1904 treaty, as Chile alleges.

Instead, Chile “brought itself into a new kind of international obligation” by repeatedly offering Bolivia some sort of access to the sea after the treaty came into force, argues Mr Rodríguez.

In 1975, for example, Chile’s dictator Augusto Pinochet, fearing war with Argentina and Peru, offered Bolivia a corridor in territory that had belonged to Peru.

Peru vetoed that plan.

It has that right under the treaty that restored Tacna to its control in 1929. No matter, says Bolivia. Chile is still bound by the obligation to negotiate that its offers gave rise to.

This line of argument leaves Chilean officials aghast. It is “unheard of”, says Heraldo Muñoz, who was Chile’s foreign minister until the president asked her cabinet to resign on May 6th (see Bello).

Bolivia is not merely asking for dialogue, which Chile would enter into, but negotiations under court order “with only one outcome”.

The ICJ has no business judging the matter.

Both countries are parties to the Pact of Bogotá, which obliges signatories to submit disputes to international tribunals.

But the pact excludes conflicts that were settled before 1948.

Even if the court claims competence, Chile is confident it will not issue a judgment that would call into question borders long settled by treaty.

The ICJ is likely to rule this year on Chile’s motion to dismiss the case, or to defer a decision until it considers Bolivia’s claim.

A finding for Bolivia would not end the saga.

Negotiations would drag on, and could wind up back in court.

No Chilean government would dare to surrender territory to Bolivia, at least not without compensation, perhaps in the form of a land swap.

Even if Chile were willing, Peru could exercise its veto again.

If Bolivia and Chile cannot resolve the dispute, they could try to work around it.

Chile admits that there is room for improvement in the free-transit regime.

Some suggest it could offer Bolivia a lease on an enclave over which it would retain sovereignty, similar to China’s former arrangement with Britain over part of Hong Kong.

But no solution short of sovereignty will satisfy Bolivia.

It “will never stop claiming”, says Bolivia’s man in The Hague.

Links :