courtesy of Audubon Alaska

From Scientific American by Margaret Krie Hobson

Special protections have also been granted for wildlife and coastal communities potentially threatened by oil spills

Early this month, the Colorado-based National Snow and Ice Data Center reported that winter sea ice levels in the Bering Sea had dropped to a record low level for this time of year.

That wasn’t surprising news to the Alaska Native villages along the state’s western coast. For the last decade, those communities have been enduring the impacts of a warming climate, from the melting tundra that’s causing waterfront homes to fall into the ocean to a lack of coastal sea ice, which traditionally protected those communities from winter storm surges.

Now the increasingly open waters are attracting new ship traffic to the Bering Strait, Bering Sea and Chukchi Sea, noted Austin Ahmasuk, a marine advocate for Kawerak, an Alaska Native regional tribal consortium.

“If you look at the ship tracts in the Bering Sea over the last 10 years, it’s been like a big bowl of spaghetti, with ships going all over the place,” said Ahmasuk, who lives in Nome, Alaska.

“The shipping industry is increasing, and all of the other things that are potential harmful threats from shipping are increasing,” he said.

Bering Strait with the GeoGarage platform (NOAA chart)

Last week, the International Maritime Organization, the United Nations’ global regulatory body for international shipping, took steps to bring some order to the growing ship traffic streaming through the Bering Strait.

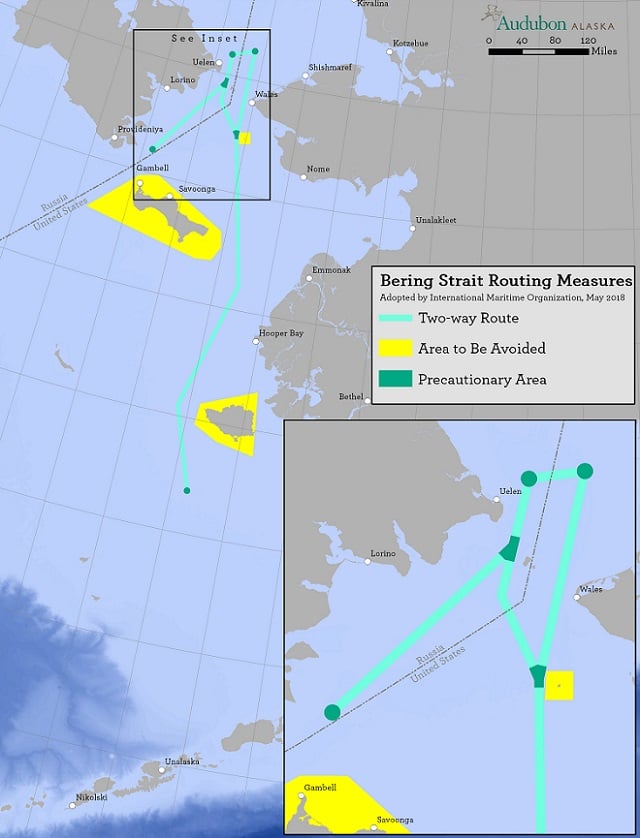

At a London meeting, the IMO’s senior technical body, the Maritime Safety Committee, accepted a proposal to create six two-way sea routes for ships traveling between the Arctic and Pacific oceans.

The plan, developed jointly by Russia and the United States, is intended to be voluntary and to only apply to all domestic and international vessels weighing 400 tons or more.

The IMO safety committee also identified six precautionary areas located along Russia’s Chukotskiy Peninsula and Alaska’s Seward Peninsula to help ships avoid shoals, reefs and islands that lie close to the two-way routes.

At the same time, the IMO provided special protections for the communities living on three Bering Strait islands that are in harm’s way from vessels in the Bering Strait.

The group accepted a proposal from the U.S. Coast Guard to designate new environmentally important “areas to be avoided” by ships traveling near Alaska’s St. Lawrence Island, Nunivak Island and King Island in the Bering Strait.

The steep, rocky cliffs on the eastern shore of Little Diomede off Alaska’s Arctic coast provide habitat for seabirds that feed in Bering Strait waters.

Diomede islands and the Russia-US frontier with the GeoGarage platform (NOAA chart)

Russia and the United States are also in talks to set up new protections around the Diomede Islands in the Bering Strait.

Those two islands are located 2 ½ miles apart, with the western Big Diomede governed by Russia and eastern Little Diomede part of Alaska.

Also at the IMO meeting, the safety committee announced plans to assess the safety, security and environmental soundness of autonomously operated ships (Greenwire, May 25).

That study will examine whether vessels operated with limited or no human help can comply with a variety of international conventions, including mandates that require all vessels to have procedures for recovering people from the water and to help tow disabled ships.

The shores between the Arctic and Pacific oceans are home to dozens of small Alaskan and Russian indigenous villages that maintain a traditional subsistence way of life.

The area also hosts one of the world’s major marine migrations of bowhead and beluga whales, Pacific walruses, and ice seals, as well as vast populations of seabirds.

Now, the increasingly open Arctic waters are beginning to attract new cargo ships, tourism, oil and gas exploration, and research and scientific activities.

The growing marine traffic is problematic in regions that are relatively shallow, particularly for ships that continue to rely on 100-year-old nautical charts, according to the IMO.

Image Courtesy: Champion Tankers

The potential impact of increased shipping on Alaska Native communities became clear two years ago when the 599-foot Norwegian tanker Champion Ebony ran aground offshore from Nunivak Island in the Bering Sea while carrying 14.2 million gallons of fuel products.

None of the fuel leaked from the ship. But the close call raised local concerns that an oil spill could have devastated local resources, Albert Williams, president of the Native village of Mekoryuk on Nunivak, said in a letter to the Obama administration.

“At the same time, our community, which would have been on the front line of an oil spill response, has virtually no infrastructure or capacity to address a risk of that scale,” Williams wrote.

The IMO’s adoption of new shipping routes and environmental protections was praised by U.S. conservation groups that have been working with coastal communities in Alaska and Russia.

Kevin Harun, Arctic program director for Pacific Environment, praised the IMO for beginning to bring order before ship traffic gets out of hand.

“Finally, decisionmakers are getting ahead of the curve to protect the environment and subsistence in advance of this increase in traffic,” he said.

Eleanor Huffines, senior officer with the Pew Charitable Trusts’ U.S. Arctic program, described the IMO action as “a significant step toward safer shipping in the Arctic.”

“These measures will keep vessels on the safest course and reduce the risk of them running aground, colliding or interfering directly with subsistence hunting,” Huffines said.

Coast Guard officials said the new shipping routes, developed in conjunction with the Russian government, will go a long way toward reducing the potential for marine casualties and environmental disasters.

“This is a big step forward as the U.S. Coast Guard continues to work together with international, interagency and maritime stakeholders to make our waterways safer, more efficient and more resilient,” said Mike Sollosi, chief of the Coast Guard’s Navigation Standards Division.

The proposal to create shipping lanes grew out of the Coast Guard’s Port Access Route Study of the Bering Strait, which was completed last year.

Sollosi said the study was the product of a decade of collaboration with international, interagency, industry and private stakeholders and extensive coordination with community residents along the coasts of Alaska.

Links :

- Maritime Executive : IMO Authorizes New Bering Sea Routing

- Seattle Times : Maritime organization approves Bering Strait shipping routes

- The Pew : New Coast Guard Measures Mean Safer Shipping in the US Arctic

No comments:

Post a Comment