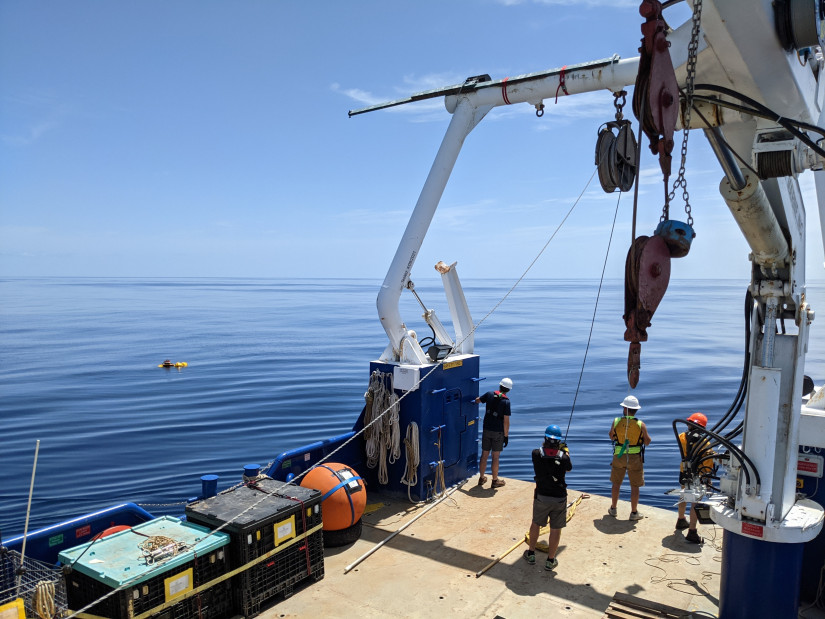

Scripps Oceanography team recovering an acoustic recording package in the Gulf of Mexico.

Scripps Oceanography team recovering an acoustic recording package in the Gulf of Mexico.From Scripps by Robert Monroe

After 2010 Deepwater Horizon incident, some Gulf of Mexico species densities declined as much as 83%

The occurrence of several whale and dolphin species in the Gulf of Mexico drastically dropped off in the decade following the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

The disaster produced a 149,000-square-kilometer (58,000-square-mile) oil slick and released a substantial amount of dispersed oil under the ocean surface.

Researchers from UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, along with their colleagues, analyzed acoustic data collected over a 10-year period during and immediately after the spill.

To study the deep-diving species that live in the waters affected by the spill, they maintained autonomous listening stations at depths of more than 915 meters (3,000 feet) in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

Their findings reveal significant declines in the presence of several species of beaked whales, sperm whales and dolphins.

The data, which captured the echolocation clicks and communication signals of a diverse set of marine mammals, documents declines of up to 30% for sperm whales and 80% for beaked whales since the spill.

The study appeared Dec. 21 in the journal Nature Communications Earth and Environment.

Study lead author Kaitlin Frasier, a research oceanographer at Scripps Oceanography, emphasized that while the study shows a strong correlation between the spill and marine mammal declines, it does not prove that the spill caused the drop-off.

She highlighted the inherent challenges in proving such a link.

“While predicting exactly where and when a disaster will occur is challenging, advancements in technology and long-term monitoring can help us better understand and address their impacts,” Frasier said.

“By focusing on innovative solutions and sustained efforts, we can improve our ability to assess and mitigate the effects of events like oil spills, even in the most challenging offshore environments.”

The spill itself was estimated to have released 210 million gallons of oil, making it the largest marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry.

This study, like others in the wake of the disaster, was initially funded by a trust fund created as part of the legal settlements following the spill.

However, it was the determination of Scripps oceanographer John Hildebrand that made the research possible, said Frasier.

Hildebrand secured emergency funding to launch the project during the period of the spill, and pieced together support from various organizations to sustain the effort over a decade, even during periods without dedicated funding.

“The Deepwater Horizon oil spill was an unprecedented disaster that demanded a nationwide response,” said Hildebrand.

“We quickly relocated instruments from southern California to the Gulf of Mexico to gather critical data needed to understand the spill’s impact on marine mammals."

Other studies unrelated to this one had previously found rates of infant dolphin deaths in coastal waters were six times higher than normal.

A 2015 study led by the NOAA linked the spill to increased deaths of bottlenose dolphins in the gulf.

Today, settlement funds remain to assist coastal remediation efforts, but offshore impacts have been difficult to assess.

“Experts predicted minimal effects and recovery within a decade, and there is no evidence that they were correct,” said Frasier.

”Those opinions were used as the basis for the post-spill damage assessment and legal settlement.

To me, this says that we still have a lot to learn about the deep ocean and how interconnected everything in it is. Gathering data is irreplaceable, and it is central to the mission of Scripps.”

While some locations outside of the 2010 surface oil slick showed increases in whale and dolphin activity, it remains unclear whether these patterns indicate animals relocating to less impacted regions.

Frasier and her colleagues continue to investigate this question using the same High-Frequency Acoustic Recording Packages (HARPs) used in the initial study, now expanded across the entire Gulf of Mexico, including in Mexican waters.

“So far we haven't found evidence suggesting an unexpectedly large number of animals in the western Gulf,” Frasier said.

“It's unlikely that the populations simply moved out of the affected area,” Frasier said.

This ongoing research highlights the importance of long-term acoustic monitoring for understanding the impacts of environmental disasters on marine life.

By improving our understanding of these impacts, this study will help future researchers estimate damage in remote, offshore habitats, and guide recovery efforts in the event of future environmental disasters, the authors said.

Links :

- Oceanographic : World's largest oil spill correlates with steep whale number declines

- EnvironmentAmerica : The impact of the Deepwater Horizon on one of Earth’s rarest whales

- Frontiers : Investigating beaked whale’s regional habitat division and local density trends near the Deepwater Horizon oil spill site through acoustics

- GeoGarage blog : Where did all the oil from the Deepwater Horizon spill go? / The biggest oil spill in US history: What we've learned ... / Unprecedented impact of Deepwater Horizon on deep ... / No protocol ready for Deepwater oil spill

No comments:

Post a Comment