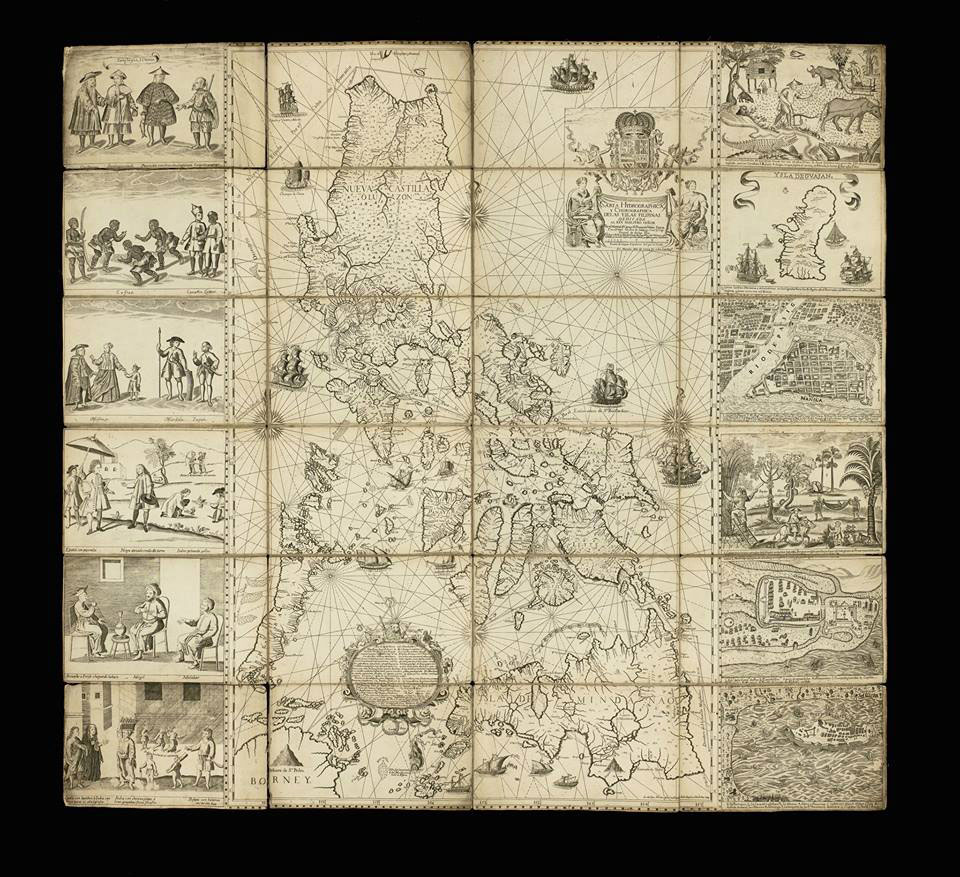

Terradepth's submersible Abraham, docked on Lake Travis outside of Austin.

Bryan Parker Founded

by a pair of former Navy SEALs, Austin-based Terradepth has ambitious

plans to deploy a fully autonomous fleet of submersibles to continually

monitor the seafloor.

Squinting against the sunlight, a team of three engineers leaned over from a floating dock on Lake Travis to pull a side panel off a blue-and-orange submersible named Abraham.

After removing a microwave-sized block of foam from the engine compartment, they peered inside, trying to puzzle out what was causing an imbalance in the buoyancy of the 25-foot-long watercraft.

For months leading up to this torrid day last June, they’d been troubleshooting one problem after another, ahead of an important test in the Gulf of Mexico.

Now, wiping sweat from their foreheads, they pondered whether to get the submersible back under the water or to call it a day and haul it back to the shop for repairs.

Getting Abraham working properly has been no easy task, in part because the startup for which the engineers work, Terradepth, wants it to do something few, if any, other autonomous underwater vehicles can—operate with no human intervention for weeks at a time.

The Austin-based company envisions deploying thousands of robotic submersibles to patrol the world’s oceans.

(The recent

OceanGate tragedy highlighted the difference between submersibles, which typically need mother ships to launch and retrieve them, and submarines, which can leave and return to port under their own power.)

Terradepth’s submersibles would operate in pairs, one charging its batteries on the surface while watching over its identical twin exploring below.

Guided by onboard artificial intelligence and equipped with an array of sensors and cameras, the robots would take turns diving to map the underwater terrain in high definition.

They’d also gather information on the water’s depth, salinity, pH levels, and temperature—continually cataloging changes.

As Terradepth sees it, that fleet could gather underwater data at a fraction of the current costs of ocean mapping, helping to provide new insights into everything from seaborne weather patterns to the best spots for new oil rigs or offshore windmills to the location of sunken treasures.

But that far-out future remains far out of reach, for now.

Mundane by comparison, the work of many of Terradepth’s thirty or so employees takes place in an industrial park in North Austin, where they create and maintain software.

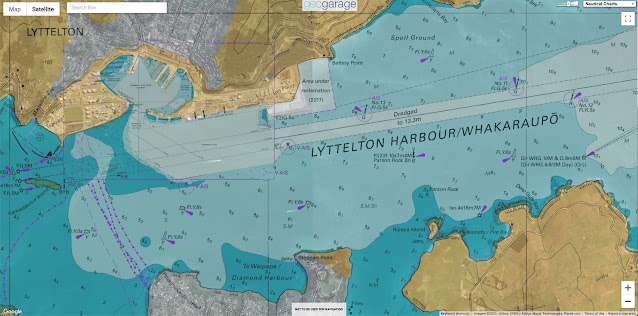

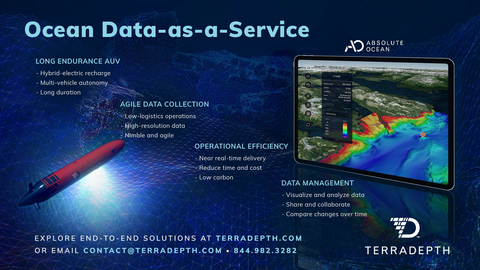

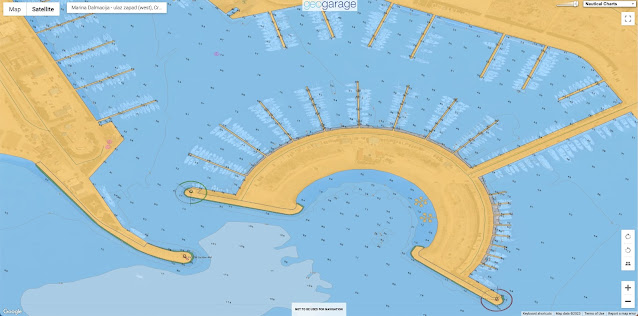

Last November, the company launched a cloud-based platform called

Absolute Ocean to which maritime mapping data can be uploaded, stored, and shared through a web browser.

That may sound simple, but Terradepth’s CEO—a bald, barrel-chested former Navy SEAL named Joe Wolfel—insists it’s a remarkable achievement because such information is often difficult to access.

“People might be surprised,” says the middle-aged executive.

“Most of the ocean-floor maritime data is still transported by mailing hard discs back and forth or emailing PDFs.”

Absolute Ocean’s technology can translate data from disparate file types into three-dimensional imagery.

The first image a user sees upon logging into the site is the blue marble of Earth floating in space.

From there, they can zoom in to view coastlines, underwater mountains, shipwrecks, and anything else that can be found in the places where detailed mapping data exists.

If that sounds a bit like

Google Earth, it’s supposed to.

Through their own mapping efforts and by assembling an enormous trove of surveys from companies around the world, Terradepth hopes to host the largest collection of oceanographic data in the world.

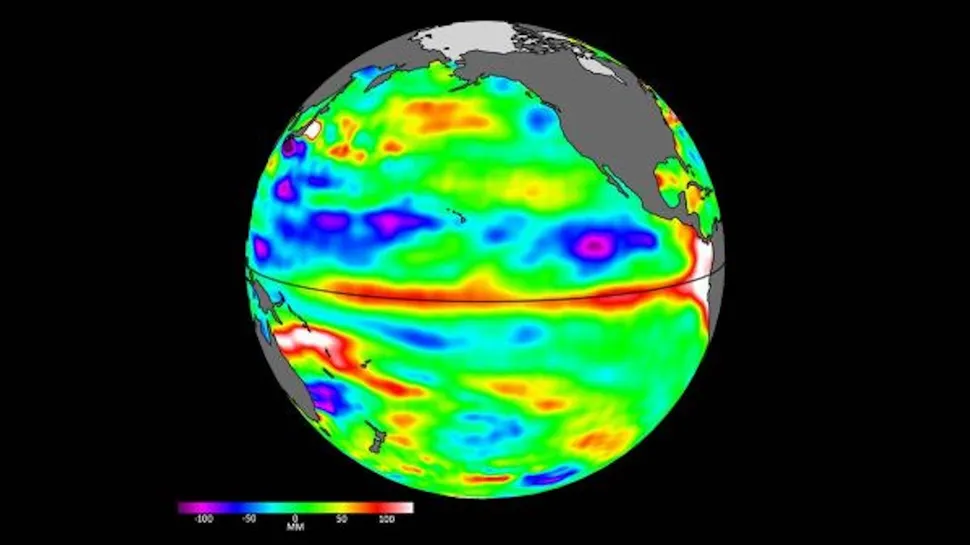

In contrast to the abundance of available real-time maps of the terrestrial environment, we know relatively little about the shape of the landscape beneath the sea.

Meanwhile, the proliferation of

offshore wind farms, deep-sea oil drilling, an ever-expanding

network of transoceanic telecom cables, and countless scientific research projects promise to bring Terradepth myriad potential customers for just such data.

For example, most states require an oceanographic survey of any proposed underwater construction site near the shore.

And even in open waters, many projects require an understanding of the topography of the seafloor, including the presence of obstacles such as sunken ships, defunct pipelines, or hydrothermal vents spewing magma.

Terradepth aims to build its business on making maritime data easier to view and share and by driving down the costs of collecting that data.

But to fully realize its vision, the company needs to get Abraham off that dock in Lake Travis and out into deeper waters, where a world of discovery still awaits.

Every grade-school kid knows that around 70 percent of the Earth’s surface is covered by water, but the oceans aren’t just vast, they’re deep.

We still have no clear picture of what’s in most of the planet’s 321 million cubic miles of water, only about 25 percent of which have been mapped in high resolution.

In recent years, undersea explorers have found

giant tube worms clinging to deepwater volcanoes near the Galapagos Islands, located the

lost city of Thonis-Heracleion off the coast of Egypt, and pinpointed the century-old wreck of

Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance in the Antarctic.

“If you go hiking in the mountains, you get a map,” says Kelly Dorgan, a biologist who studies marine invertebrates at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab in Alabama.

“The ocean is so under-studied that we’re not looking for a path through the mountains; we’re looking for, ‘where is there a mountain?’ ”

Indeed, in 2005, the nuclear-powered USS San Francisco submarine

ran into an underwater mountain near Guam while traveling at full speed.

One crewman was killed and dozens of others injured because the Navy’s maps were inaccurate.

Much of our understanding of the ocean floor comes from imperfect data collected by aircraft.

Flying low, planes and helicopters and drones use water-penetrating lasers to measure the elevation of the seafloor.

This technique is called light detection and ranging, or lidar.

The deeper or darker the water, the less accurate lidar readings tend to be, resulting in maps that can be off by hundreds of feet—falsely indicating there’s a valley, for example, where there’s actually a mountain—says Michael Starek, chief scientist at the Conrad Blucher Institute, an ocean data research outfit that’s part of Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi.

The USS San Francisco accident got Wolfel and his Terradepth cofounder, Judson Kauffman, talking while they served together as Navy SEALs in Baghdad, he says, and it “stuck in the back of our heads” even after they left the military.

In 2012, they founded a Nashville-based firm called Exbellum that helped place special-forces veterans in jobs, and five years later, they were among the founders of

Desert Door Distillery, which makes sotol in Driftwood, just southwest of Austin.

In November 2017, over a few Shiners at the since-shuttered Austin barbecue joint Freedmen’s, Kauffman asked, “Why can’t we do for ocean research what SpaceX is doing for space?”

Their opportunity to try doing that came the next year, thanks to Seagate Technology, the California-based data storage giant.

Wolfel had consulted for Seagate while working for retired Army general Stanley McChrystal’s McChrystal Group several years earlier.

He’d gotten to know Seagate’s then-CEO, Steve Luczo, who offered to financially back any good idea for a start-up that Wolfel could come up with—so long as it involved robotics and data storage.

Seagate’s venture-capital division seeded Terradepth in 2018 with $8 million.

(It has since raised a total of over $30 million, according to Crunchbase.)

Terradepth is far from the only company wading into the ocean mapping business.

Its global competition includes some well-financed Texas firms, including

Ocean Infinity, a company with dual headquarters in Austin and the United Kingdom, and Houston-based

Nauticus Robotics.

Ocean Infinity, which garnered publicity after joining the search for

Malaysia Airlines flight 370 after it crashed in 2014, already operates a small fleet of crewless robotic surface ships capable of transporting multiple robotic submersibles to a mapping site.

And Nauticus has a fleet of twenty autonomous submersibles that can not only map the seabed but also transform underwater into robots capable of repairing structures such as oil rigs.

Terradepth hopes to set itself apart with its use of paired autonomous submersibles that can take turns acting as the surface vessel for each other, one feeding geolocation data to its partner that’s diving up to two thousand meters with a camera and multiple sonar sensors for mapping.

When the submerged vehicle runs low on battery power, it resurfaces to recharge its battery on a diesel-powered combustion engine, and its counterpart would take its place below.

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) estimates that ocean mapping typically costs as much as $100,000 a day, and a

UNESCO report from 2017 indicates that most of that cost comes from the crew and fuel necessary to power the surface vessel.

Wolfel hopes that Terradepth’s submersibles can someday be produced for $1 million each and operate for about $10,000 a day, though that cost could vary greatly depending on the scope of a particular client’s project.

Such numbers, at this stage, remain highly speculative, considering that a week after the summer 2022 testing in Lake Travis, a broken valve on Abraham resulted in a months-long work stoppage that reset the company’s timeline.

Terradepth now expects an ocean test of the submersible sometime this summer.

Steve Hall, the former vice chair of the IOC, with almost three decades of experience in underwater exploration and mapping in the United Kingdom, said he’s not aware of any other companies trying to launch an effort to map the oceans purely with unmanned systems.

“If you can get it to work,” he said, noting an important caveat, “it’s transformative.”

Terradepth needs its robotic submersibles not only to avoid running into underwater mountains but also to be able to distinguish between, say, a boulder on the seafloor and a shipwreck.

To do that, it first must show the robot what those two things look like.

At Lake Travis, the company went through a laborious process of teaching the sub by labeling 1,600 manmade objects on the seabed that had been pinged by Abraham’s sonar.

“It took weeks,” Wolfel says.

“We have the highest-resolution map of Lake Travis.”

Still, there’s a long way to go.

For deep ocean exploration, the company will need to train the submersibles to identify tens of thousands of objects.

That could include anything from unexploded munitions to those hydrothermal vents where giant tube worms live.

Even as Terradepth works toward creating its own fleet, it has already deployed a handful of autonomous submersibles on mapping projects for paying clients.

Made by California-based

Teledyne Technologies, these watercraft, called Gavias, range from between 6.5 and 14 feet long and have to be managed by a manned surface vessel.

Wolfel and his team were recently commissioned to check on the condition of an underwater pipeline.

They determined that it had become partially exposed when it should’ve been completely buried in the seafloor.

This condition could pose an environmental hazard, potentially leading to the contents of the pipeline leaking out into the sea.

According to Wolfel, they were able to show the client a clear visual rendering of the issue in Absolute Ocean in just over an hour.

Such operations account for the bulk of Terradepth’s earnings, while the remainder comes from Absolute Ocean.

The platform operates as a paid subscription service, at a cost of up to several thousand dollars a year.

Academic institutions can also obtain licenses for a nominal fee.

Companies that use Absolute Ocean can keep their proprietary data all to themselves or share it with the world.

Terradepth also plans to use its platform to sell mapping data provided by third parties, including TCarta, a Denver firm that specializes in using satellites to generate topographical maps of the ocean floor.

As of now, Absolute Ocean has about 250 subscribers, but Terradepth hopes to triple that number by the end of the year.

Among the earliest customers were hydrographic survey firms such as S. T. Hudson Engineers in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, which specializes in the design of ports; Orange Force Marine, a Canadian purveyor of marine supply and survey services; and Arobotnx, an Indian industrial robotics and automation firm.

In the summer of 2022, Absolute Ocean

was also tapped to be the “data visualization and exploration tool” for a project seeking to create and make publicly available a map of the entire ocean floor.

That effort is being spearheaded by a nonprofit called Seabed 2030 that’s jointly operated by the Nippon Foundation, an ocean philanthropy in Japan, and an international organization focused on understanding the depth measurements of the oceans.

Seabed 2030 hopes having such knowledge more widespread will help humankind confront global challenges, including climate change and overfishing.

Seabed 2030 contributors, such as private ship captains who collect sonar readings along the path of their journeys, will be able to upload their data into Absolute Ocean, where it will be converted into interactive maps.

Steve Hall serves as Seabed 2030’s head of partnerships and sees enormous value in Terradepth’s web platform.

“You can kind of click and play is the nice thing with the Terradepth product,” he says.

“Within a few hours you’re going to have a pretty good understanding of how to visualize data.

” That may sound simple, but it fundamentally shifts the experience of reading ocean data from trying to grasp raw numbers as XYZ coordinates into an intuitive, user-friendly package.

Terradepth’s involvement in Seabed 2030 could give it a role in achieving some of the loftier intentions Wolfel touts for the company, like aiding in the discovery of chemicals in the unexplored deep that could fight diseases, including cancers.

That’s not as farfetched as it might seem.

Multiple medical breakthroughs have come from sea creatures, including tunicate, a marine invertebrate animal that has been used to successfully treat non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

For now, cancer and climate change aren’t the day-to-day focus of Terradepth.

Instead, the company remains months, if not years, away from a fully realized version of itself.

But Wolfel sees the path he’s on as an essential part of convincing the world to pay closer attention to our own Earth instead of dreaming of new worlds.

“We’re sitting there talking about creating an ocean on Mars because we’re assuming that this planet is done,” he says with an edge of frustration.

He’s hoping Terradepth can be part of a different solution: “Bring the resources to bear to understand our own ocean better, and it can save the planet.”

Links :

Another AI analysis of Russian Navy ships in Sevastopol by Satim Inc.

Another AI analysis of Russian Navy ships in Sevastopol by Satim Inc. image: getty images

image: getty images