Saturday, February 1, 2020

Bjorn Dunkerbeck - The Movie - Trailer

Friday, January 31, 2020

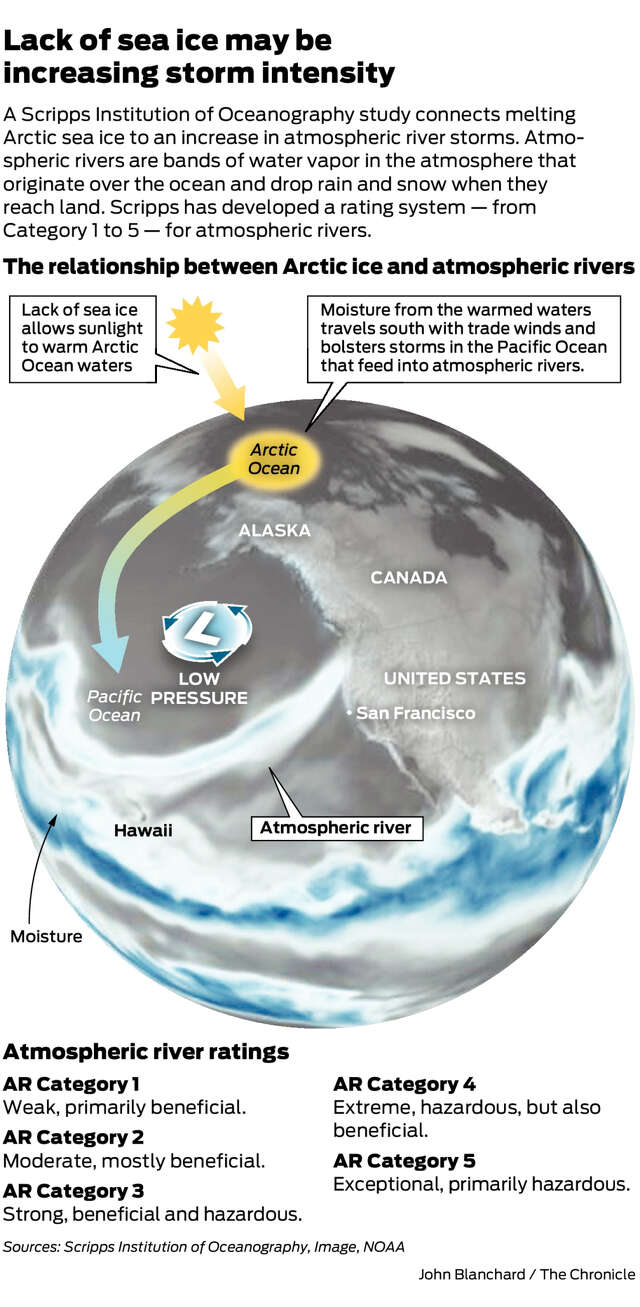

A new consequence of Arctic Sea Ice melt: changing weather at the Equator

From Scripps by Robert Monroe

Two researchers present evidence today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that the accelerating melt of Arctic sea ice is linked to weather patterns near the equator in the Pacific Ocean.

Charles Kennel, a physicist and the former director of Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, and colleague Elena Yulaeva said there is strong evidence that the ice melt sets a chain of events in motion that sends cold air equatorward in the upper atmosphere.

The two used computer analysis of historical data to identify which atmospheric phenomena also change as Arctic ice diminishes, as it has steadily since 1999.

Among the variables that seemed to move in lockstep with ice melt were intensifying trade winds at the equator in the Central Pacific Ocean.

The study marks the first time that researchers have looked at both world regions together in this context.

“There’s a definite relationship and a change in tropical Pacific climate,” said Kennel.

“There’s now a network of consistent correlations.”

The Pacific Ocean is considered one of the biggest, if not the biggest, drivers of global climate.

What originates in the Pacific, including patterns of warm equatorial water known as El Niño and La Niña, affects weather experienced on every continent.

Thus the melt of Arctic sea ice could have a global reach by influencing the influencer of weather set in motion around the world.

Sea ice melt affects climate by first raising the temperature of surface water in the Arctic Ocean. While most sunlight bounces off the ice, the dark water absorbs about 93 percent of sunlight “like applying a flame at the bottom of the atmosphere,” Kennel said.

The warmth creates convection of air that reaches the boundary of the troposphere and the stratosphere above it.

The air has nowhere to go but south.

This movement goes hand in hand with contortions of typical weather patterns that have caused frigid “polar vortex” weather in the U.S. Midwest and deadly flooding in Asia in recent years.

Though many researchers had thought that air originating in the Arctic couldn’t make it to the equator, Kennel and Yulaeva said their work suggests it does.

One consequence is that the nature of El Niño storms changes. Classical El Niños feature build-ups of warm water at the eastern end of the Pacific Ocean off South America.

Kennel and Yulaeva’s analyses indicate that El Niños starting in the Central Pacific Ocean are the ones that respond to the arrival of Arctic air near the equator.

Kennel suggested that since so much of California’s rain comes from atmospheric river storms that develop in the Central Pacific, the Arctic-Tropics connection merits further study.

He added that their research suggests but does not rigorously demonstrate that changes in Arctic sea ice are causing changes at the equator.

It does, however, “point the way toward studies that could do that,” he said.

Links :

- Mongabay : Melting Arctic sea ice may be altering winds, weather at ...

- Phys : Research links sea ice retreat with tropical phenomena ...

- Hydro : Consequence of Arctic Sea Ice Melt: Changing Weather at the Equator

- Inside Climate news : Dwindling Arctic Sea Ice May Affect Tropical Weather Patterns

- SFIST : New Study Finds Direct Link Between Melting Arctic Ice and Extreme Weather In California

- SFChronicle : Atmospheric rivers that hit California getting a boost from melting Arctic ice

Thursday, January 30, 2020

EU vessels will no longer have automatic access to UK fishing waters

From The Guardian by Fiona Harvey

EU vessels will no longer have automatic access to UK fishing waters

The automatic right of EU vessels to fish in British waters, in accordance with the EU’s common fisheries policy, is to be ended under the fisheries bill introduced to parliament today.

There will also be measures to ensure sustainable fishing and “climate-smart” fishing in UK waters, added since the last version of the bill which had to be abandoned.

This is in line with the government’s environmental commitments, and provisions to provide financial support to fishing communities.

But campaigners said the bill fell short of ministers’ pledges to protect dwindling fish stocks and contained too many loopholes.

In this Tuesday, Jan. 28, 2020 photo, a fishing vessel is docked at Kilkeel harbor in Northern Ireland. The United Kingdom and the European Union are parting ways on Friday and one of the first issues to address is what will happen to the fishing grounds they shared.

In this Tuesday, Jan. 28, 2020 photo, a fishing vessel is docked at Kilkeel harbor in Northern Ireland. The United Kingdom and the European Union are parting ways on Friday and one of the first issues to address is what will happen to the fishing grounds they shared.Access to UK waters is likely to be a key bargaining chip in negotiations with the EU over a new trade deal.

Several European politicians and officials have made it clear they think British access to the EU’s lucrative financial services markets ought to be dependent on keeping the access European fishing fleets currently enjoy to UK waters.

The UK’s fishing fleet employs about 11,000 people and is worth less than £1bn to the national economy.

However, fishing became a major issue during the referendum campaign.

Owing to concessions given by successive British governments since the 1970s, EU member states take a much greater proportion of the fish in UK waters than the national fleet.

Theresa Villiers, environment secretary, said: “This new bill takes back control of our waters, enabling the UK to create a sustainable, profitable fishing industry for our coastal communities, while securing the long term health of British fisheries.

Leaving the EU’s failed common fisheries policies is one of the most important benefits of Brexit.

It means we can create a fairer system.”

Barrie Deas, chief executive of the National Federation of Fishermen’s Organisations, said: “New provisions in the bill will mean the UK will take into account the impacts of climate change on its fisheries, with a new objective to move us towards ‘climate-smart’ fishing.”

However, campaigners are concerned that ministers could seek to water down the government’s commitments to sustainable fishing.

They called for more clarity on whether greater quotas would be allocated to smaller boats, which are more sustainable than huge trawlers, and called for the government to introduce cameras on vessels to ensure that sustainable practices were being followed, such as monitoring whether vessels were discarding fish.

Patrick Killoran, at Greener UK, said: “This [bill] will only work if the government closes loopholes in the last bill that allowed ministers to exceed fishing limits.

The focus we can expect on rights and access over the next few months must be matched by more detail on how the government will actually ensure sustainable fishing.”

Sarah Denman, UK environment lawyer at ClientEarth, said: “The bill falls far short of the government’s election manifesto promise to secure sustainable fisheries.

A clear requirement to set sustainable fishing limits is vital to protect fish populations and work towards ocean recovery, but this is absent from the bill [and] key conservation measures to safeguard overfished species will be removed once the UK leaves the EU, and will not be replaced in the bill.”

She said the negotiations with the EU would be “an important test to see if the government is serious about managing our fisheries sustainably for the benefit of the marine environment and coastal communities”.

Links :

- BBC : Laws for sustainable fishing planned post-Brexit

- The Telegraph : Foreign boats will need licences to fish in British waters after Brexit under new legislation being brought before MPs

- Gov.uk : Sustainable fisheries enshrined in law as UK leaves the EU / Fishing regulations as the UK leaves the EU

- FT : Brexit: why fishing threatens to derail EU-UK trade talks

- AP : Post-Brexit talks gear up for fish fight between EU, UK

- iNews : Fishing in the Brexit era : what to expect as the UK tries to secure a greater share in Brussels

Wednesday, January 29, 2020

They’re stealthy at sea, but they can’t hide from the albatross

Credit...Alexandre Corbeau

From NYTimes by Katherine Kornei

Researchers outfitted 169 seabirds with radar detectors to pinpoint vessels that had turned off their transponders.

There’s a lot of ocean out there, and boats engaging in illegal fishing or human trafficking have good reason to hide.

But even the stealthiest vessels — the ones that turn off their transponders — aren’t completely invisible: Albatrosses, outfitted with radar detectors, can spot them, new research has shown.

And a lot of ships may be trying to disappear.

Roughly a third of vessels in the Southern Indian Ocean were not broadcasting their whereabouts, the bird patrol revealed.

Albatrosses are ideal sentinels of the open ocean, said Henri Weimerskirch, a marine ecologist at a French National Center for Scientific Research in Chizé, France, and the lead author of the new study published on Monday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“They are large birds, they travel over huge distances and they are very attracted by fishing vessels.”

Weimerskirch et al./PNAS

Dr. Weimerskirch and his colleagues visited albatross breeding colonies on the Amsterdam, Crozet and Kerguelen Islands, French outposts in the Southern Indian Ocean.

The team attached roughly two-ounce data loggers to 169 adult and juvenile birds.

The equipment consisted of a GPS antenna, a radar detector and an antenna for transmitting data to a constellation of satellites.

It took two people about 10 minutes to tape one of the solar-powered loggers onto the back feathers of an albatross.

Despite the birds’ size — the largest one the researchers handled tipped the scale at 26 pounds — they were “very easy” to work with, said Dr. Weimerskirch.

From November 2018 through May 2019, the researchers watched as breeding adults foraged at sea for 10 to 15 days at a time, flying thousands of miles per trip, and as juveniles left the colony.

The birds traversed a total area of roughly 18 million square miles, about five times the size of the United States, always on the lookout for radar signals.

Fishing boats are regularly in those waters, seeking tuna and Patagonian toothfish — otherwise known as Chilean sea bass — that frequent areas near the islands.

The feathery dragnet recorded radar blips from 353 vessels, which used radar to navigate and detect other boats.

But only 253 of the boats had their Automatic Identification System transponder turned on, which broadcasts a ship’s identity, position, course, speed and other information, as required by International Maritime Organization regulations.

One hundred ships, or 28 percent, were silent.

They might have been fishing without a license or transferring illegal catches onto cargo vessels, Dr.

Weimerskirch said.

“A lot of fishing boats prefer not to be located.”

When the researchers looked only at boats in international waters, they found an even higher percentage (37 percent) of stealth vessels.

There have been no previous estimates of boats evading detection, Dr. Weimerskirch said.

“It’s a surprise that the number is so high.”

These observations can help government officials pinpoint suspicious vessels, the team suggested, because both the birds’ radar detections and Automatic Identification System information can be downloaded nearly in real time.

Daniel Pauly, a fisheries biologist at the University of British Columbia who was not involved in the research, said the use of the technology was a “real achievement.”

Dr. Weimerskirch and his colleagues are planning similar investigations in places like New Zealand, Hawaii and South Georgia, an island in the South Atlantic.

They hope to show that other species of seabirds, like petrels, can also be ocean sentinels.

The first step is to make the equipment smaller, Dr. Weimerskirch said.

“We’re working on miniaturizing the loggers.”

Links :

- Phys : Revenge of the albatross: seabirds expose illicit fishing

- Science Mag : Seabird 'cops' spy on sneaky fishing vessels

- Smithsonian : Albatrosses Outfitted With GPS Trackers Detect Illegal Fishing ...

- Audubon : Albatross Wearing Data Trackers Are Exposing Illegal Fishing Boats

- Le Monde (in French) : Des albatros pour repérer les pêcheurs illégaux dans les mers australes

- CNRS (French) : Quelle est l’ampleur de la pêche illégale ? Les albatros répondent

- The Conversation : Worst marine heatwave on record killed one million seabirds ...

- EcoWatch : Death of 1 Million Seabirds Tied to Massive ‘Blob’ of Hot Water in the Pacific

- The Guardian : Huge ‘hot blob’ in Pacific Ocean killed nearly a million seabirds

Tuesday, January 28, 2020

The long ocean voyage that helped find the flaws in GPS

This article recounts a project by DLR, the German Aerospace Center, to assess maritime GPS disruption in various areas - port, waterway, coastal, and open ocean.

Spoiler alert - They found GPS disruption everywhere. Even in the open ocean.

From Fortune by Katherine Dunn

This article is part of the Fortune series, "When GPS goes wrong."

- Into the ‘crucible’: How the government responds when GPS goes down

- How GPS went from being the tech everyone hated to the tech everyone needs

Mysterious GPS outages are wracking the shipping industry

In late April 2017, a commercial container ship left port in Hamburg, Germany.

The ship looped around western Europe and through the Mediterranean, then passed through the Suez Canal to the Middle East, on its way to Asia.

It was the first of many times the Basle Express would traverse a path between the continents, traveling thousands of miles and heading as far afield as far eastern Russia, before ending its journey in Singapore 10 months later.

The vessel itself was sailing standard commercial seaways.

But it carried special cargo: On board were two specially built receivers developed by the German Aerospace Center, Germany’s counterpart to NASA, to detect the frequency of disruption to GPS and other satellite navigation systems along its route.

GPS interference was a problem that, by 2017, was anecdotally on the rise, according to multiple maritime experts and government agencies—and it was beginning to make the shipping industry nervous.

(See Fortune’s feature story on the phenomenon here.)

The interference had been linked to “jamming” and “spoofing” techniques, which interrupt genuine satellite signals, either by disrupting them entirely or producing fake signals that can mislead a receiver.

Commercially available “jammers”, though illegal, were cheap, and easy to find online, and disruption had increasingly been reported in geopolitical hotspots, particularly in the Black Sea around Russia-annexed Crimea.

Later that year, after the Basle Express began its voyage, authorities in Norway and Finland would report outages during NATO drills.

But nobody seemed to know exactly how often GPS interruptions were occurring, how strong they were, and how they impacted shipping, one of the world’s most global industries.

The German Aerospace Center team gathered data that would help demonstrate the sheer scale of the problem.

And what the team found surprised even the researchers themselves.

“It was a big deal!” says Emilio Pérez Marcos, one of the lead researchers on the study and a researcher in the Institute of Communications and Navigation at the aerospace center.

“We expected to see some interference, accidental ones (maybe due to malfunction of equipment and such), but never so much and by no means so powerful.”

Interruptions from the Suez to Shanghai

The data from the Basle Express, which was first presented in September 2017 and has been expanded on since, presented a striking picture.

The crew documented interference with GPS—usually taking the form of much stronger conflicting signals—at some of the world’s largest seaports, including Jeddah in Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Shanghai, and less often, on the open sea.

At least 140 “strong” cases were documented, defined as powerful enough to disrupt the GPS receivers of a regular commercial ship.

The researchers documented two particularly strong cases of interference, one in the Suez Canal, where the researcher's receivers lost all GPS signals for hours, and another in Jebel Ali, a major commercial port just south of Dubai.

Both those locations are relatively close to geopolitical conflict zones where other interruptions of GPS have been documented.

(The Suez has witnessed a pattern of interruptions dating from mid-2017.)

The researchers have been quick to note that they can’t draw conclusions on which of the interference incidents they documented were caused intentionally, and which were accidental.

They could guess, says Pérez Marcos, but not know for sure—and GPS interference is notoriously difficult to attribute.

Still, the Basle Express research has been one of the biggest contributions to a growing body of evidence about the scale of GPS disruption.

Since its first research was published, reports from the U.S.

Coast Guard Navigation Center has mapped out GPS risk areas, and a European Union-funded monitoring project that covered numerous international highways and ports recorded interference events in the tens of thousands.

That evidence is stirring a desire for a definitive response in the global shipping community.

In June 2019, a letter to the U.S.

Coast Guard signed by 14 maritime organizations cited the German study and asked the agency to address the problem of interference with the International Maritime Organization, the UN agency for shipping.

(The Coast Guard recently told Fortune that it’s still considering what action to take.)

Meanwhile, reports of disruption from commercial ships have been spreading: Through 2018 and 2019, alleged jamming and spoofing was reported across the East Mediterranean, near the North Korean border, in the northern Scandinavian Arctic, around the Port of Shanghai, and in the Strait of Hormuz, the shipping chokepoint that separates the Persian Gulf states from export markets in Asia.

Coping with a ‘menace’

In total, this tide of evidence suggests that GPS is not as resilient as we’ve come to expect, and that the commercial shipping industry, in particular, needs to consider alternatives.

After all, the most widely used standard vessels and their equipment were developed in an era where unreliable GPS was impossible to imagine, points out Pérez Marcos.

“They simply were not designed to cope with that menace,” he says.

To prepare, the industry may need to make a substantial investment: in technology, including pricey but more robust anti-jamming antennae; in training their crews more regularly in how to navigate without GPS—or, more likely, in both.

“When the GPS service is not available, it all comes down to two factors,” says Pérez Marcos.

“Are there any other means of positioning and timing to keep navigating? Or, is the crew capable to navigate by old/more traditional nautical means?”

Without such back-ups, some crews would likely be completely fine in the event of a GPS disruption, Pérez Marcos points out, while others would be completely lost.

But like many in the industry, the researcher says his deeper concerns revolve around what’s to come: a looming age of automation in global shipping in which, as in many other industries, humans will be taken "out of the loop.”

That will increasingly leave machines to assess what is a real or reliable GPS signal while at sea—and what to do next.

That is a question that shall keep us scientists busy for the next years.”

Links :

- Fortune : Mysterious GPS outages are wracking the shipping industry / How GPS went from the tech everyone hated to the tech everyone needs / Into the ‘crucible’: How the government responds when GPS goes down

- ION : Interference and Spoofing Detection for GNSS Maritime Applications using Direction of Arrival and Conformal Antenna Array

Monday, January 27, 2020

NOAA releases 2020 hydrographic survey season plans

From NOAA

NOAA hydrographic survey ships and contractors are preparing for the 2020 hydrographic survey season.

The ships collect bathymetric data (i.e.

map the seafloor) to support nautical charting, modeling, and research, but also collect other environmental data to support a variety of ecosystem sciences.

NOAA considers hydrographic survey requests from stakeholders such as marine pilots, local port authorities, the Coast Guard, and the boating community, and also consider other hydrographic and NOAA science priorities in determining where to survey and when.

Visit our “living” story map to find out more about our mapping projects and if a hydrographic vessel will be in your area this year!

Great Lakes

Chicago, Illinois – This project is located along the southernmost point of Lake Michigan, which includes the Chicago Harbor and portions of the Indiana and Michigan shorelines.

Much of this 371 square nautical mile survey area has not been surveyed since the late 1940s.

Atlantic Coast

Gardiners Bay, New York – Gardiners Bay is home to recreational, tourism, and ferry vessels transiting from Long Island Sound to the north and south sides of Shelter Island.

The bay was last surveyed in the 1930s.

Long Island Sound, New York – This project encompasses a large area of shoreline that is home to almost eight million people, and includes the highly trafficked lower Hudson River and Green River.

Central Chesapeake Bay, Virginia – Survey vintage predates 1950 for the majority of the project area, despite vessels transiting within close proximity to the seafloor.

This survey will close a critical gap in existing modern hydrographic data between the entrance to Chesapeake Bay up through Baltimore, Maryland.

Onslow Bay, North Carolina – This project covers a 362 square nautical mile area seaward of Morehead City and Cape Lookout Shoals.

Data from this project will supersede 1970 vintage chart data, in an area of shifting shoals.

Canaveral, Florida – This project is located approximately six nautical miles southeast of Cape Canaveral.

Much of the 376 square nautical mile survey area has not been surveyed since 1930.

The types of marine vessels visiting Port Canaveral include passenger vessels, cargo ships, tug boats, pleasure crafts, tankers, sailing vessels, fishing vessels, and special crafts.

Gulf of Mexico

Apalachicola, Florida – This project covers an area offshore of Apalachicola Bay and Joseph Bay, Florida.

The survey will provide updated bathymetry and feature data to address concerns of migrating shoals.

Approaches to Houston, Texas – This survey covers approximately 163 square nautical miles of Trinity Bay, Galveston Bay, Houston Ship Channel, and Buffalo Bayou.

Modern high-resolution surveys of these areas are important for navigational safety and as a tool to help planners and researchers model and manage issues as diverse as floodwater movement and oyster reef restoration.

Approaches to Galveston, Texas – This survey covers approximately 610 square nautical miles between the Galveston Bay and Sabine Bank Channels in an area that has not been surveyed since 1963.

This survey will identify changes to the bathymetry since previous mapping efforts.

Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary – This project will support NOAA’s Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management in their efforts to effectively protect ecologically sensitive and important areas within the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico.

The nine banks to be surveyed in this project have not been surveyed to modern standards.

Alaska

Norton Sound – This survey will improve the safety of maritime traffic and services available to remote coastal communities by reducing the current risk of unknown water depths.

The last hydrographic surveys of this area occurred in the late 1890s.

Tide gauges will also be installed to provide tide data in an area currently underserved with tide observations.

Newenham – This survey will improve the safety of maritime traffic and services available to Bethel and communities around Goodnews Bay by reducing the current navigation risk due to unknown hazards.

Glacier Bay – Frequently visited by cruise ships and tourist vessels, modern surveys will increase maritime safety and address uncharted areas exposed by receding glaciers in this area.

Southeast Alaska – This project will provide modern bathymetric data for Whale Pass, Thomas Bay, and Endicott Arm at Dawes Glacier.

Similar to Glacier Bay, this new data will identify hazards and changes to the seafloor, provide data for nautical charting products, and improve maritime safety.

South Pacific

Commonwealth of the Mariana Islands – A multidisciplinary NOAA team will map the waters around Guam, Saipan, Rota, Tinian, and other islands in the northern part of the Commonwealth of the Mariana Islands.

The team will map bathymetry, collect backscatter data, and characterize habitat, while simultaneously performing coral reef assessment dives and collecting other oceanographic observations.

NOAA’s four hydrographic survey ships –Thomas Jefferson, Ferdinand Hassler, Rainier, and Fairweather – are operated and maintained by the Office of Marine and Aviation Operations, with hydrographic survey projects managed by the Office of Coast Survey.

What’s the difference between private weather companies and the National Weather Service?

From Forbes by Jim Foerster

Many people don’t realize there are private weather companies that consult with businesses of all ...

Weather plays a significant role in business.

It impacts the U.S.

gross national product by approximately $1 trillion each year, and weather information is used by over 95% of all companies in the U.S. based on several recent studies.

According to the National Weather Service (NWS), weather creates $13 billion of value to businesses each year in the U.S.

Neither the public nor private sector by itself can address the needs of all weather consumers.

The efforts of the NWS and private weather companies go hand in hand to make our industry as successful and productive as it is.

The relationship is a very symbiotic one that continues to evolve and grow.

Many people don’t realize there are private weather companies that consult with businesses of all kinds and sizes every day around critical decisions.

In fact, private weather forecasting is a $7 billion industry, according to a 2017 National Weather Service study, and it’s continuing to grow at a rate of around 10-15% each year.

As with any good partnership, both parties contribute in significant ways, capitalizing on their unique strengths.

The NWS has the funding and long-term vision to make capital investments and develop an infrastructure that produces a wealth of weather information, including surface observations, radar, satellite data, as well as running multiple numerical weather models that predict the future state of the atmosphere.

This information helps the government meet its primary public safety obligation.

It’s not financially practical for a private sector company to produce and collect such massive amounts of weather information because it wouldn’t provide a return on investment.

Thus, these functions have traditionally been executed on a large scale by a government agency.

The NWS makes its data freely available, thus allowing the private sector to use the information for its purposes.

Indeed, this sharing of data provides the backbone of the American weather enterprise.

The NWS has an essential role providing warnings of hazardous weather and other weather-related products to organizations and the public for purposes of protection, safety and general information.

We are all familiar with watches and warnings issued by the NWS for various severe weather events, including large hail, winds more than 55 knots, tornadoes, heavy rain events, tropical storms, and significant snowstorms.

The NWS provides consistent, high-quality forecasts and services for the country as a whole, but in turn does not customize forecasts, watches or warnings to any individual or business.

Commercial weather companies utilize the data made available by the NWS’s parent agency, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) along with data from private networks and other global government agencies to create the value-added services tailored to customer’s needs.

For example, many commercial weather providers statistically combine forecasts from the NOAA GFS model, the European ECMWF model, and their own, higher resolution models to create highly-accurate global forecasts.

Further, most commercial weather providers have a staff of expert meteorologists that curate these combined forecasts to produce the final forecasts that go out to clients and more important than ever, consult with customers around the risk or impact the weather will have on their operations.

Unlike the NWS, a commercial weather provider prepares custom forecasts for a variety of purposes and precise locations.

For example, a commercial weather provider can issue forecasts for the exact location of an oil rig’s operation in the ocean.

It can detail the time of critical wind changes or frontal passages and provide alerts about the onset of significant rain, lightning or thunderstorms that might affect their operations.

Private forecasters can also provide customized forecasts and risk consultation for farmers, large festivals and events, retail interests and many other corporate interests.

A strength of the private sector is its ability to effectively tailor and communicate weather information and the risk it will bring to both consumers and businesses.

While the government produces essential weather data and general forecasts for the nation, it lacks the readymade audience that many sizable private weather companies have developed.

The private sector can broadcast weather watches and warnings issued by the NWS through apps, television, websites, and social media.

Commercial weather providers have also been creative in providing weather information that helps people plan their outdoor activities for the hour, day and week due to the detailed knowledge they obtain about the decisions being made.

This also allows private sector meteorologists to work directly with customers to define their needs and create analytics that are a combination of weather information and customers information, creating significant value for customer work flows, safety plans, etc.

Commercial weather providers also provide value to large, global companies that seek seamless services anywhere in the world, including in places where the National Meteorological Centers do not provide coverage.

With more and more extreme weather events around the globe, having the resources of both the public and private weather services benefits businesses and consumers alike.

Links :

Sunday, January 26, 2020

AC75 foils training

The British team for 36th America's Cup winter training in Cagliari on the island of Sardegna, Italia. Skippered by Ben Ainslie the crew are testing their new boat.