Two biologists from the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge survey seabird colonies on the cliffs of Hall Island, just north of St.

Matthew Island, in the Bering Sea.

Matthew Island, in the Bering Sea.

From Hakai Mag by Sarah Gilman / Photos by Nathaniel Wilder

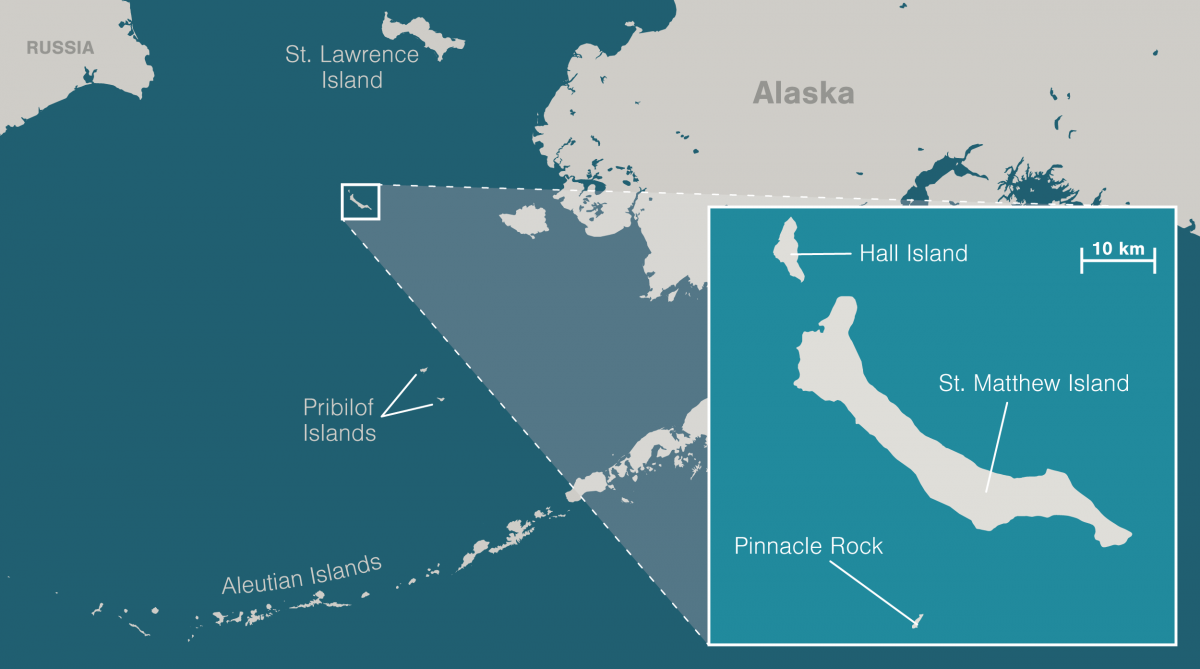

St. Matthew Island is said to be the most remote place in Alaska.

Marooned in the Bering Sea halfway to Siberia, it is well over 300 kilometers and a 24-hour ship ride from the nearest human settlements.

It looks fittingly forbidding, the way it emerges from its drape of fog like the dark spread of a wing.

Curved, treeless mountains crowd its sliver of land, plunging in sudden cliffs where they meet the surf.

To St. Matthew’s north lies the smaller, more precipitous island of Hall.

A castle of stone called Pinnacle stands guard off St. Matthew’s southern flank.

To set foot on this scatter of land surrounded by endless ocean is to feel yourself swallowed by the nowhere at the center of a drowned compass rose.

My head swims a little as I peer into a shallow pit on St. Matthew’s northwestern tip.

It’s late July in 2019, and the air buzzes with the chitters of the island’s endemic singing voles.

Wildflowers and cotton grass constellate the tundra that has grown over the depression at my feet, but around 400 years ago, it was a house, dug partway into the earth to keep out the elements.

It’s the oldest human sign on the island, the only prehistoric house ever found here.

A lichen-crusted whale jawbone points downhill toward the sea, the rose’s due-north needle.

Compared with more sheltered bays and beaches on the island’s eastern side, it would have been a relatively harsh place to settle.

Storms regularly slam this coast with the full force of the open ocean.

As many as 300 polar bears used to summer here, before Russians and Americans hunted them out in the late 1800s.

Evidence suggests that the pit house’s occupants likely didn’t use it for more than a season, according to Dennis Griffin, an archaeologist who’s worked on the archipelago since 2002.

Excavations of the site have turned up enough to suggest that people of the Thule culture—precursors to the Inuit and Yup’ik who now inhabit Alaska’s northwestern coasts—built it.

But Griffin has found no sign of a hearth, and only a thin layer of artifacts.

A lichen-crusted whale jawbone points downhill toward Sarichef Strait from the site of a 400-year-old Thule house site on St. Matthew Island, Alaska.

The Unangan, or Aleut, people from the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands to the south tell a story of the son of a chief who discovered the then uninhabited Pribilofs after he was blown off course.

He overwintered there, and then returned home by kayak the following spring.

The Yup’ik from St. Lawrence Island to the north have a similar story, about hunters who found themselves on a strange island, where they waited for the opportunity to walk home over the sea ice.

Griffin believes something similar may have befallen the people who dug this house, and they sheltered here while waiting for their chance to leave.

Maybe they made it, he will tell me later.

Or maybe they didn’t: “A polar bear could have gotten them.”

In North America, many people think of wilderness as a place mostly untouched by humans; the United States defines it this way in law.

This idea is a construct of the recent colonial past.

Before European invasion, Indigenous peoples lived in, hunted in, and managed most of the continent’s wild lands.

St. Matthew’s archipelago, designated as official wilderness in 1970, and as part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge in 1980, would have had much to offer them, too: freshwater lakes teeming with fish, many of the same plants that mainland cultures ate, ample seabirds and marine mammals to hunt.

And yet, because St. Matthew is so far-flung, the solitary pit house suggests that even Alaska’s expert seafaring Indigenous peoples may never have been more than accidental visitors here.

Others who’ve followed have arrived with the help of significant infrastructure or institutions.

None remained long.

Map data by OpenStreetMap via ArcGIS

St Matthew island with the GeoGarage platform (NOAA nautical raster chart)

I came to these islands aboard a ship called the Tiĝlax̂ [TEKH-lah] to tag along with scientists studying the seabirds that nest on the archipelago’s cliffs.

But I also wanted to see what it felt like to be in a place that so thoroughly rejects human presence.

On this, the last full day of our expedition, as the scientists rush to collect data and pack up camps on the other side of the island, the pit house seems a better vantage than most to reflect.

I lower myself into the depression, scanning the sea, the bands of sunlight flickering across the tundra on this unusually clear day.

I imagine watching for winter’s sea ice, waiting for it to come.

I imagine watching for polar bears, hoping they will not.

You never know, a retired refuge biologist had said to me before I boarded the Tiĝlax̂.

“I would keep my eyes out.

If you see something big and white out there, look at it twice.”

Once, these islands were mountains, waypoints on the subcontinent of Beringia that joined North America and Asia.

Then the ocean swallowed the land around the peaks, hid them away in thick summer fogs, made them lonely.

With no people resident long enough to keep their history, they became the sort of place where “discovery” could be perennial.

Lieutenant Ivan Synd of the Russian navy, oblivious to the pit house, believed he was first to find the largest island, in 1766.

He named it for the Christian apostle Matthew.

Captain James Cook believed he discovered it in 1778, and called it Gore.

The whalers who came upon the archipelago later called it, simply, “the Bear Islands.”

Around the winter of 1809–1810, a party of Russians and Unangans decamped here to hunt bears for fur.

Depending on what source you consult, many of the Russians died of scurvy, while the Unangans survived, or some or most of the party perished when the sea mammals they relied on moved beyond the range of their hunts, or all were so tormented by polar bears that they had to leave.

Indeed, when naturalist Henry Elliott visited the islands in 1874, he found them swarming with bruins.

“Judge our astonishment at finding hundreds of large polar bears … lazily sleeping in grassy hollows, or digging up grass and other roots, browsing like hogs,” Elliott wrote, though he seemed to find them less terrifying than interesting and tasty.

After his party killed some, he noted that the steaks were of “excellent quality.”

An aerial view of the northwestern corner of St. Matthew Island.

The small grouping of uninhabited islands is over 300 kilometers across the Bering Sea from the mainland, making it the most remote location in Alaska.

Even after the bears were gone, the archipelago remained a difficult place for people.

The fog was endless; the weather, a banshee; the isolation, extreme.

In 1916, the Arctic power schooner Great Bear ran afoul of the mists and wrecked on Pinnacle.

The crew used whaleboats to move about 20 tonnes of supplies to St. Matthew to set up a camp and wait for help.

A man named N. H. Bokum managed to build a sort of transmitter from odds and ends, and climbed each night to a clifftop to tap out SOS calls.

But he gave up after concluding that the soggy air interfered with its operation.

Growing restless as the weeks passed, men brandished knives over the ham when the cook tried to ration it.

Had they not been rescued after 18 days, Great Bear owner John Borden later said, this desperation would have been “the first taste of what the winter would have brought.”

US servicemen stationed on St. Matthew during the Second World War got a more thorough sampling of the island’s winter extremes.

In 1943, the US Coast Guard established a long-range navigation (Loran) site on the southwestern coast of the island, part of a network that helped fighter planes and warships orient on the Pacific with the help of regular pulses of radio waves.

Snow at the Loran station drifted up to around eight meters deep, and “blizzards of hurricane velocity” lasted an average of 10 days.

Sea ice surrounded the island for about seven months of the year.

When a plane dropped the mail several kilometers away during the coldest time of year, the men had to form three crews and rotate in shifts just to retrieve it, dragging a toboggan of survival supplies as they went.

The other seasons weren’t much more hospitable.

One day, five servicemen vanished on a boat errand, despite calm seas.

Mostly, the island raged with wind and rain, turning the tundra to a “sea of mud.”

It took more than 600 bags of cement just to set foundations for the station’s Quonset huts.

The coast guard, worried how the men would fare in such conditions if they were cut off from resupply, introduced a herd of 29 reindeer to St. Matthew as a food stock in 1944.

But the war ended, and the men left.

The reindeer population, without predators, exploded.

By 1963, there were 6,000.

By 1964, nearly all were gone.

Winter had taken them.

These days, the Loran station is little more than a towering pole anchored by metal cables to a bluff above the beach, surrounded by a wide fan of debris.

On the fifth day of our week-long expedition, several of us walk the sagging remains of an old road to the site.

Near the pole that still stands, a second has fallen, a third, a fourth.

I find the square concrete pillars of the Quonset huts’ foundations.

A toilet lies alone on a rise, bowl facing inland.

I pause next to a biometrician named Aaron Christ, as he shoots photos of a pile of rusting barrels that shriek with the scent of diesel.

“We’re great at building wondrous things,” he says after a moment.

“We’re terrible at tearing them down and cleaning them up.”

The beach is slowly reclaiming a disintegrating barel cache at the abandoned coast guard long-range navigation station on St. Matthew Island.

And yet, the tundra seems to be slowly reclaiming most of it.

Monkshood and dwarf willow grow thick and spongy over the road.

Moss and lichen finger over broken metal and jagged plywood, pulling them down.

At other sites of brief occupation, it’s the same.

The earth consumes the beams of fallen cabins that seasonal fox trappers erected, likely before the Great Depression.

The sea has swept away a hut that visiting scientists built near a beach in the 1950s.

When the coast guard rescued the Great Bear crew in 1916, they left everything behind.

Griffin, the archaeologist, found little but scattered coal when he visited the site of the camp in 2018.

Fishers and servicemen may have looted some, but what was too trashed for salvage—perhaps the gramophone, the cameras, the bottles of champagne—seems to have washed away or swum down into the soil.

The last of the straggling reindeer, a lone, lame female, disappeared in the 1980s.

For a long time, reindeer skulls salted the island.

Now, most are gone.

The few I see are buried to their antler tips, as if submerged in rising green water.

Life here grows back, grows over, forgets.

Not invincibly resilient, but determined and sure.

On Hall Island, I see a songbird nesting in a cache of ancient batteries.

And red foxes, having replaced most of St.

Matthew’s native Arctic foxes after crossing on sea ice, have dug dens beneath the Loran building sites and several pieces of debris.

The voles sing and sing.

The island is theirs.

The island is its own.

The next morning dawns dusky, light and clouds stained sepia by smoke blown from wildfires burning in distant forests.

I spot something big and white as I walk across St. Matthew’s flat southern lobe and freeze, squinting.

The white begins to move.

To sprint, really.

Not a bear, as the retired biologist had hinted, but two swans on foot.

Three cygnets trundle in their wake.

As they turn toward me, I spot a flash of orange porpoising through the grass behind them: a red fox.

The cygnets seem unaware of their pursuer, but their pursuer is aware of me.

It veers from the chase to settle a couple of meters away—scraggly, gold eyed, and mottled as the lichen on the cliffs.

It drops to its side and rubs luxuriantly against a rock for a few minutes, then springs away in a possessed zigzag, leaving me giggling.

After it’s gone, I kneel to sniff the rock.

It smells like dirt.

I rub my own hair against it, just to say “hey.”

A red fox comes in for closer inspection of human visitors on the south side of St.

Matthew Island.

The island grouping only gets visitors (researchers and tourists) every few years so wildlife has little to fear.

As I continue on, I notice that objects in the distance often appear to be one thing, then resolve into another.

Ribs of driftwood turn out to be whale bones.

A putrid walrus carcass turns out to be the wave-pummeled rootball of a tree.

Unlikely artifacts without stories—a ladder, a metal pontoon—occasionally jag from the ground, deposited far inland, I guess, by storms.

When I close my eyes, I have the vague feeling that waves roll through my body.

“Dock rock,” someone will call this later: the sensation, after you have spent time on a ship, of the sea carried with you onto land, of land assuming the phantom motion of water beneath your feet.

It occurs to me that to truly arrive on St. Matthew, you have to lose your bearings enough to feel the line between the two blur.

Disoriented, I can sense the landscape as fluid, a shapeshifter as sure as the rootball and whale bones—something that remakes itself from mountains to islands, that scatters and swallows signs left by those who pass across.

I consider the island’s eroding edges.

Some cliffs in old photos have fallen away or buckled into sea stacks.

I look at the few shafts of sun out on the clear water, sepia light touching dark mats of kelp on the Bering’s floor.

Whole worlds submerged or pulverized to cobble, sand, and silt, down there.

A calving of land into sea, the redistribution of earth into unknowable futures.

A good place to remember that we are each so brief.

That we never stand on solid ground.

The wind whips strands of hair out of my hood and into my eyes as I press my palms into the floor of the pit house.

It feels firm enough, for now.

That it’s still visible after a few centuries reassures me—a small anchor against the dragging currents of this place.

Eventually, though, I get cold and clamber out.

I need to return to my camp near where the Tiĝlax̂ waits at anchor; we’ll be setting course south back over the Bering toward other islands and airports in the morning.

But first, I aim overland for a high, gray whaleback of ridge a few kilometers away that I have admired from the ship since our arrival.

The sunlight that striped the hills this morning has faded.

An afternoon fog descends as I meander over electric green grass, then climb, hand over hand, up a ribbon of steep talus.

I top out into nothingness.

One of the biologists had told me, when we first discussed my wandering alone, that the fog closes in without warning; that, when this happened, I would want a GPS to help me find my way back.

Mine is malfunctioning, so I go by feel, keeping the steep drop of the ridge’s face on my left, surprised by flats and peaks I don’t remember seeing from below.

I begin to wonder if I have accidentally gone down the ridge’s gently sloping backside instead of walking its top.

The fog thickens until I can see only a meter or two ahead.

Thickens again, until I, too, vanish—erased as completely as the dark tracery of path I left through the grass below soon will be.

Then, abruptly, the fog breaks and the way down the mountain comes clear.

Relieved, I weave back through the hills and, on the crest of the last, see the Tiĝlax̂ in the placid bay below.

The ship blows its foghorn in a long salute as I lift my hand to the sky.

Links :

No comments:

Post a Comment