The yacht Alive approaching Tasmania’s fabled Organ Pipes during last year’s Sydney Hobart race.

Credit... Studio Borlenghi/Rolex, via Agence France-Presse

From NYTimes by David Schmidt

Experienced sailors say not to approach it as one event, but as several.

Sailboat races have a way of developing their own lore, especially when there are boat-breaking waves and fast-moving weather systems.

It is easy to think that the annual Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race, which begins on Thursday, involves just three things: the start, the spin cycle and the finish.

Race veterans say that approaching this rough-and-tumble, 628-nautical-mile racecourse as a monolith can be overwhelming.

Instead, they say, a compartmentalized mind-set is required to deal with the race’s seamanship and navigational challenges, and it is best to break the race down to segments, or chapters, planning how to handle them one at a time.

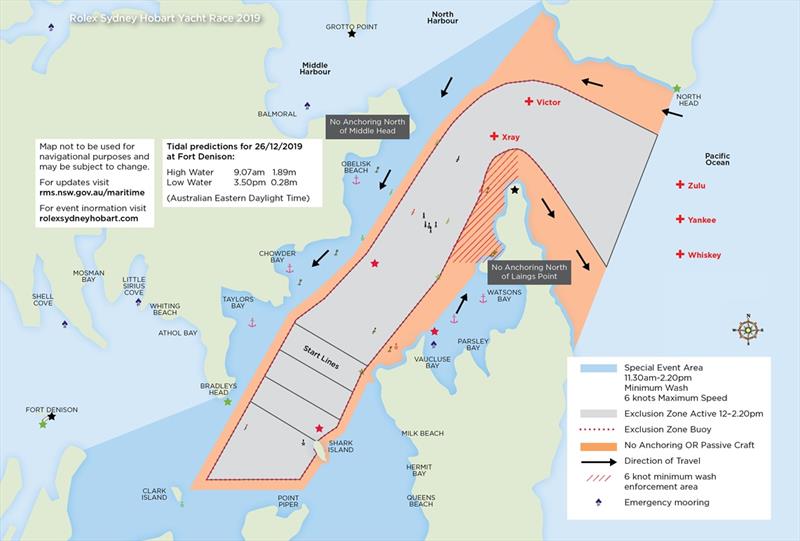

The race begins in Sydney Harbor before punching out past Sydney Heads and turning south to parallel the New South Wales coastline.

The East Australia Current, which flows generally south at one to four knots, pushes boats along, but this benefit can boomerang.

Hook into a northerly breeze, so that the wind and current align, and sailors enjoy a magic-carpet ride toward Bass Strait.

Encounter a “southerly buster,” which delivers stiff winds from the south that oppose the current, and the seas stack up.

Fast.

Hit this wind-against-current scenario in or near Bass Strait, the shallow body of water separating Australia from Tasmania, and the seas can quickly become a nautical nightmare.

This happened in 1993, when two-thirds of the fleet abandoned racing, and again in the tragic 1998 race when six sailors died and five yachts sank.

“This race is not to be underestimated,” said Will Oxley of Australia, a navigator who has won the race twice but also ended up in a life raft once.

He says the wind typically blows from the northeast for a few days before transitioning to a southerly.

“I’ve done about 350,000 miles of sailing, and my worst experiences with sea state have been in this race,” he added.

“There aren’t many races that you’d see 50 knots upwind.”

Next to be negotiated are the Tasmanian coastline, Storm Bay and the River Derwent, an upriver slog of about 11 nautical miles where the wind typically dwindles or dies each evening before rekindling the next morning.

Worse still, the tidal river usually flows seaward, pushing yachts backward.

Because of this, fortunes are often won or lost on the River Derwent.

For Oxley, who plans to race on Matt Allen’s Botin 52 Ichi Ban this year, the chapters are the start, the New South Wales coast, crossing Bass Strait, the Tasmanian coast and the 40-mile journey across Storm Bay and up the River Derwent.

Ken Read, the former skipper of Comanche, the 100-foot super maxi (now LDV Comanche) that he commanded to a line-honors win (first across the finish line) in 2015, says he does not mind racing in nasty conditions but hates anticipating them.

“If there’s one consistent thing about this race, something weird is going to happen, and you’d better be prepared,” he said.

Weather, of course, is critical.

“You definitely divide the race into chapters,” Read said.

But for him, “it’s purely weather-driven.”

Instead of geographical distinctions, Read and Stan Honey, an America’s Cup and Volvo Ocean Race-winning navigator who helped LDV Comanche set the racecourse’s time record in 2017, view the racecourse through a meteorological lens.

“It’s almost guaranteed that you’re going through a strong front that time of year,” said Read, describing the race’s chapters as the start, the prefront, the frontal transition, after a weather front passes, approaching Storm Bay and finally the River Derwent.

“I talk about one weather transition,” he said, adding that record-setting boats like Comanche can often outsail a second bad-weather cycle.

“The little boats are likely looking at two transitions, so it’s twice as hard and two to three times the exposure.”

Honey described negotiating the low-pressure systems as jaywalking across a busy highway.

Comanche sprints while the smaller boats stroll.

“If you have a tough race, you could have two to four days of a hard southwesterly bash all the way,” said Lindsay May, a Sydney native who has won the race four times.

This year’s race will be his 47th consecutive start.

“It’s a lottery and needs good understanding of the forecast to best navigate the route, plus a lot of luck.”

And luck, of course, is ephemeral.

Some Sydney Hobart sailors divide the race by geography or weather.

Others think in hours.

“This race is not to be underestimated,” said Will Oxley, a two-time winner.

Credit...Carlo Borlenghi/Rolex

“I think in segments, but they’re not the same, year to year,” Honey said.

“A common transition is the southerly change, which sees wind against the East Australia Current,” he said, describing an often-violent sea.

“The wind picks up quickly under a characteristic roll cloud — it’s a frightening sight.”

Honey described his chapters as the start, entering the offshore winds, negotiating the East Australia Current, crossing Bass Strait, approaching Tasmania, picking the best lane — or angle — toward Tasmania, crossing Storm Bay and sailing up the River Derwent.

Picking the best lane toward Tasmania can be crucial, and Honey and Oxley described it as potentially one of the race’s biggest navigational problems.

“I’m looking if the weather models line up, but typically I use historical and real-time data and my gut to make the decision,” Oxley said.

A casual weekend sail this is not.

“It’s my favorite race as a navigator, there are so many moving parts,” Honey said, before admitting that it is not always pleasant.

“In almost every other yacht race, you start and go someplace nice.

With the Sydney Hobart, you start someplace warm and nice and go someplace cold and windy.”

While some divide the race by geography or weather, others think in hours.

“In basic terms, it’s all about when you get to Storm Bay,” said Roger Badham, a meteorologist who has been preparing pre-race weather reports since 1982.

“The timing to get to Storm Bay and the Derwent is critical,” he added.

“God, in his wisdom, determines the handicap winner.”

The River Derwent “can be a long and painful exercise,” Oxley said.

“The best time to arrive in Storm Bay is in the afternoon.

The Derwent can take 45 minutes or six hours.”

Because of this, Oxley said, the race can sometimes be further simplified into two chapters: the run of 588 nautical miles to Tasman Island and the 40-nautical-mile race from Tasman Island to the finish.

While the rules preclude Badham from offering weather services once racing begins, his pre-race reports break the course into 12-hour increments.

“The current changes weekly, but the winds are changing hourly or daily,” he said.

“Initial conditions are the most important thing.”

To win, Badham said, yachts must marry periods of fast sailing with their big-picture objective of knowing when and where the wind will change, and where the boats want to be positioned relative to this transition.

“It’s primarily a near-coastal race except Bass Strait,” he said.

Wind on the rumbline, the most direct line across a body of water, “is highly influenced by land masses, day and night variation and sea-breeze effects.” Because of this, he said, it is critical to understand the influences of geography, time and weather transitions.

Ultimately, Badham said, if team leadership is not looking at the racecourse in terms of all three, odds are good that those sailors will be languishing in the River Derwent or maneuvering through a southerly buster, while others are already across the finish line.

Links :

No comments:

Post a Comment