From Surfline

How one break in Portugal creates the world's largest waves

A wave that produces the 80-foot Guinness world record for largest wave ever ridden needs no introduction.

Even to the non-surfing community, little is needed when mainstream media regularly runs photos and videos of every XXL swell that hits the small Portuguese fishing town.

Hell, CNN’s Anderson Cooper even rode through the rocks on the back of a ski — piloted by none other than previous world record holder (also caught at Nazaré), Garrett McNamara.

Nazaré is well known for good reason.

It regularly produces the largest rideable waves on planet Earth.

And thanks to the ultimate deepwater canyon set up, Nazaré’s surf size potential is only bound by the size and direction of the swell it receives.

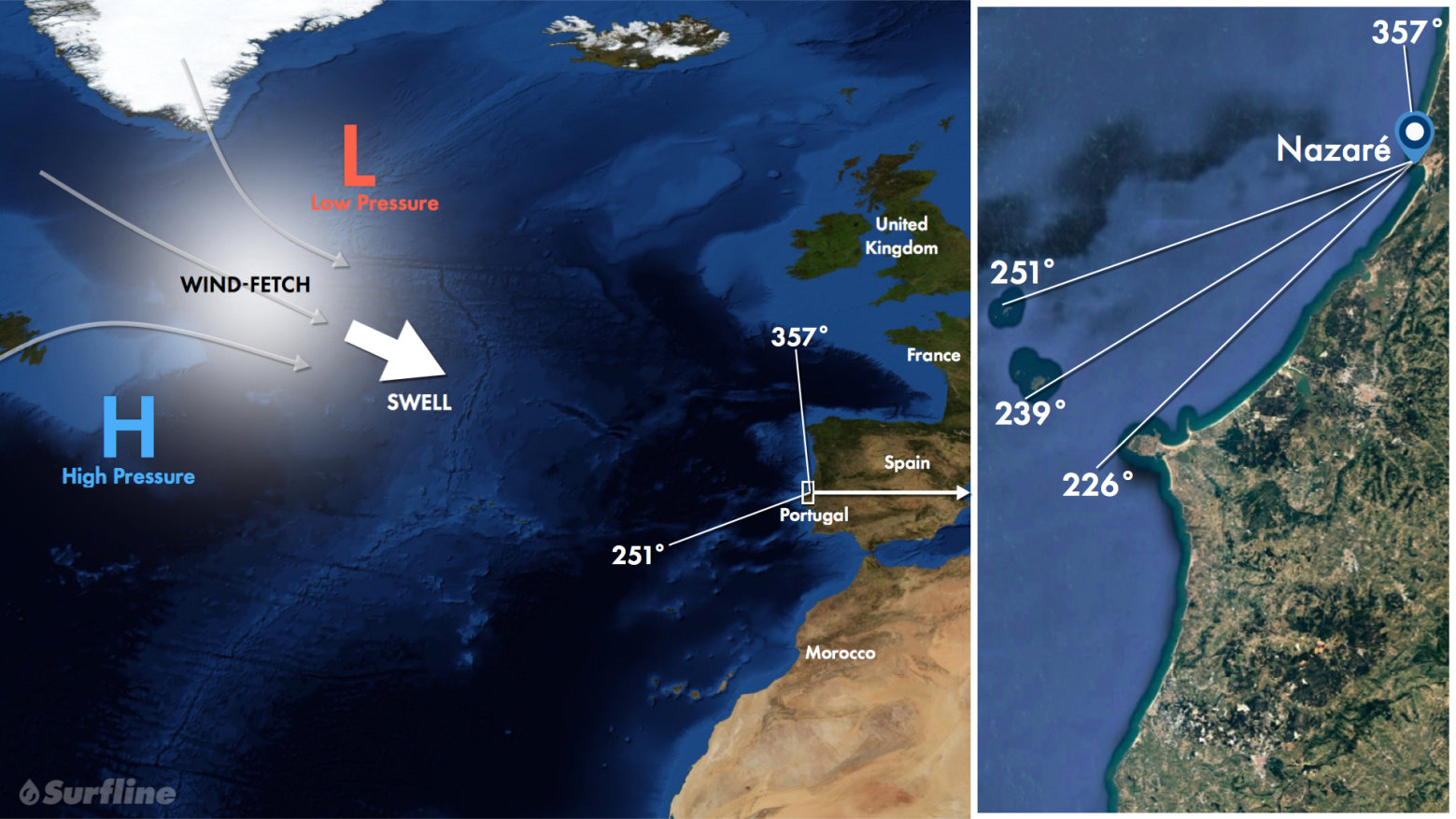

Swell Source

- Strongest swells of year from October through April when intense mid-latitude frontal lows track eastward across the North Atlantic, interacting with adjacent high pressure.

- Typical storm track moves towards Europe helping maximize swell potential.

- Strongest swells from WNW to NW, are often consistent, ranging from short to long period.

- Travel time from one to five days.

- Peak hurricane season from mid-August through mid-October can offer a variety of swell directions. Recurving tropical cyclones often undergo extratropical transition (most common, October) or enhance developing winter storms. Tropical systems can impact the region with wind and weather, like Cyclone Leslie in October 2018.

- Local windswell events do occur and can provide fun surf. Events are not as strong as above mentioned swell sources and do not produce the signature XL surf.

- Nazaré’s swell window is technically open from SW (226°) to N (357°). West to NW angled swells are strongest and most common; WNW swells are ideal.

- Between the Peniche peninsula at 226° and 251° lies a small group of islands known as the Berlengas Archipelago. A fraction of swell energy filters through these islands and are not as strong as more prominent West-NW swells.

- Southerly angled swells are usually local windswell events (e.g., ahead of an approaching front), often coinciding with unfavorable onshore wind.

- Nazaré receives more northerly angled swells up to 357°. North-northwest to N swells are not a favorable direction — shorter period swells generally sweep across the beach, longer period swells see an occasional canyon set that is too crossed up. Wave amplification through refraction by the canyon and associated constructive interference is not as impactful from the north.

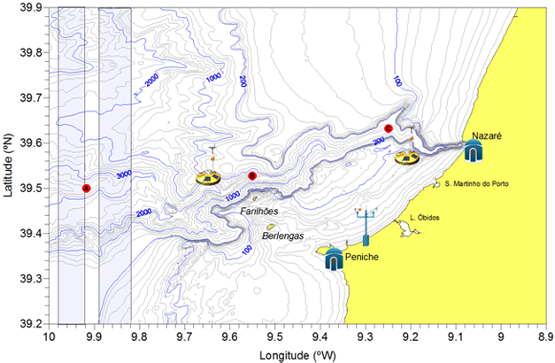

Bathymetry

Bathymetry is vital in how waves behave when approaching and breaking along shore, refracting energy into or away from different locations with each variation in swell direction or period.

The surf at certain points can be amplified to greater heights, while other spots are left in a swell void.

And the best spot on the planet to observe extreme wave refraction is Nazaré.

The large, deepwater Nazaré Canyon has the potential to significantly amplify the surf at the beach just to the north of the bay.

Wave-face height can multiply three, four, even five times the offshore deepwater swell height.

But this magnification is highly dependent on the incoming swell angle and period.

Generally, Nazaré favors a longer period swell from the WNW.

Energy in longer period swells extends deeper within the water column, feeling the contours of the ocean bottom sooner, and with a greater degree of effect.

Since swells always refract toward shallower water, longer period swells start to turn and bend sooner and more effectively.

For Nazaré, there is a steep contrast between the large and deep canyon running offshore and the much shallower ridge that lines the northern slope.

This canyon/ridge relationship extends a long distance far offshore all the way up to the break.

The portion of the swell running through the deep canyon maintains a greater percentage of its raw open ocean energy and forward speed closer to shore.

And upon interacting with the adjacent ridge, much of this energy will refract out of the canyon and focus back in toward the break.

The various bends of the canyon also play a role, helping create a more complex scenario of refracting and converging waves.

Meanwhile, the inbound swell traveling over the shallower water north of the canyon starts to gradually slow down and shoal when nearing the coast — and much of this energy focuses toward Nazaré as well.

The result is a compression of these refracting swell lines as they converge at the break, amplifying the waves.

However, there is another key factor at work besides just refractive pileup that helps contribute to the extreme magnification of the waves here, and that is constructive interference (Note – A spot like the Wedge also has this X-factor going on).

After extensive research on the bathymetry, running various swell scenarios through our high-powered computer simulations, and athlete observations, we do know the “magic numbers” for the canyon to perform at its maximum potential.

And the direction is just as important as the period.

Given the unique layout of this underwater landscape, incoming long period swells from the WNW are ideal for Nazaré.

These swells have just enough west in them to allow the canyon to refract at its fullest potential, yet just enough north that most of the swell is refracting back toward this particular stretch of beach, instead of away to the south.

The north component allows the portion of the swell not running through the canyon to converge with the waves refracting out of the canyon — a combo of NW and SW waves in the surf zone.

If there is too much north in the swell, then the canyon has difficulty refracting swell back toward the north, thus providing less energy and lowering the potential for larger surf.

The sets that do refract from the canyon are almost too peaky with more slopey, mushy shoulders.

There is often more current running on these more northerly angled swells as well.

For W to WSW swells, the refracting energy from the canyon is more evenly split to the north and south, also lowering the potential for larger surf at Nazaré.

SW swells are partially shadowed by offshore islands.

The surf is not as peaky on these swells, as west lines north of the canyon square up more to the coast with less convergence from waves refracting from the canyon.

For more southerly angled swells, the canyon refracts more energy to areas to the south, considerably lowering the refracting factor and peaky nature of Nazaré.

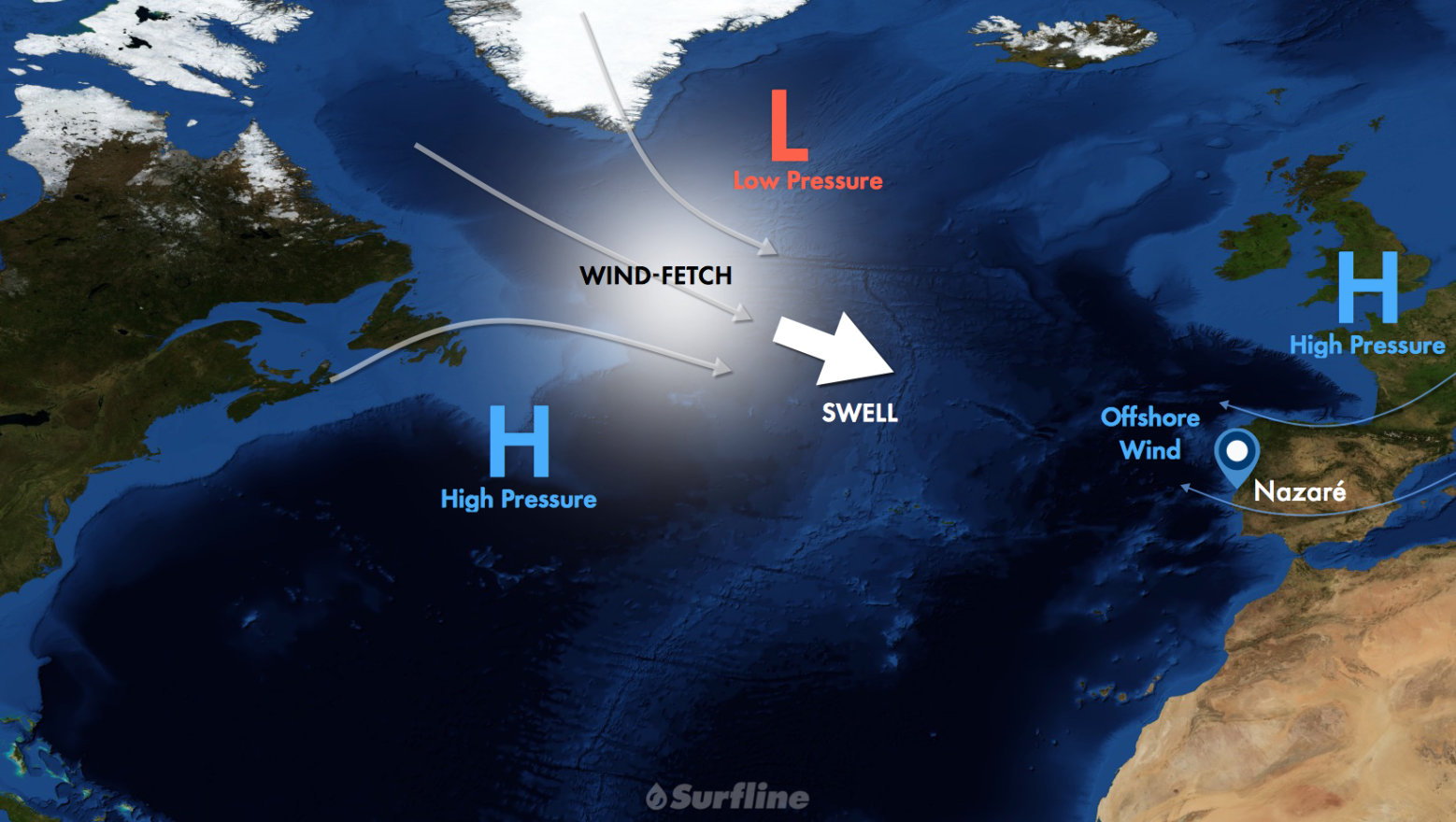

Wind

Like most spots, Nazaré prefers calm or light to moderate offshore wind (east to southeast).

Strong offshore wind can create hazardous conditions and is almost as problematic as an onshore wind, especially in big surf.

Strong offshores make it very difficult to paddle into waves and creates surface chop running up the wave faces.

Bigger, faster-moving waves have a greater opposition to stronger offshore flow, aggravating the sea surface even more.

Located on the far southwestern edge of Europe, Nazaré fares better than those at higher latitudes when it comes to severe winter weather.

Systems tracking through the higher latitudes, or storms that lift northward before nearing Europe, can provide good swell with less adverse local weather.

But storms tracking through the lower latitudes can bring poor wind and weather along with swell.

Approaching fronts often bring onshore winds and stormy conditions to the region.

High pressure building in behind these fronts, either over the region or to the north or northeast, turns the wind offshore and improves local weather.

Nazaré can handle light onshores as the waves themselves block the wind on big days and the cliffs shelter the waves from a southerly wind.

Best Conditions for Nazaré

- Best Tide: Mid, prefers incoming

- Best Swell Direction: West-Northwest to Northwest

- Best Swell Period: Longer period

- Best Wind: Calm or light to moderate offshore (east-southeast)

- Best Size: Works on all sizes, no limit on max size

- Best Season: Fall generally best, winter and spring very solid too

- Resources for Nazaré

- Nazare Spot Forecast

- High Resolution Wind Forecast for Nazare-Peniche

- Zona Oeste — Portugal Regional Forecast

- Live HD Cams — Nazare Overview Cam and Beach-view Cam

- Nazare Go XXL Live

- Nazare — Zona Oeste Regional Forecast

- Live HD Beach-level View of Nazare

- Nazare Hourly High Resolution Wind Forecast

- GeoGarage blog : Empties : Nazaré / See what it's like to ride the tallest wave ever surfed/

Nazaré, black Carnival / Big surf in Nazare : a closer look / Surf spots roar back to life as strong Atlantic swell ... / Big wave surfing Nazaré Portugal

No comments:

Post a Comment