Saturday, May 6, 2017

Friday, May 5, 2017

Image of the week : An island carved by water

NASA acquired October 17, 2016

From NASA

The story of Long Island began with ice.

As glaciers retreated at the end of the last Ice Age, they dropped and piled up hills of sediment.

When the ice melted and seas rose, those piles of glacial debris were surrounded by the sea. Stretching out into the Atlantic like a giant fish, the island continues to change.

Thousands of years later, water still re-sculpts the island’s shoreline.

On October 17, 2016, the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 captured this image of Long Island’s East End.

While the North Shore is characterized by craggy inlets and peninsulas, the South Shore is lined with smooth, protective sand bars—the result of constantly pounding waves.

Between the branching tails of the East End lies Gardiners Island, which spans more than 3,300 acres and is closed to the public—a source of curiosity given its proximity to population-dense Long Island.

In the 1600s, Gardiners was believed to have a cache of pirate gold.

Modern scientists appreciate it for another form of booty: its rich coastal geology.

As glaciers retreated at the end of the last Ice Age, they dropped and piled up hills of sediment.

When the ice melted and seas rose, those piles of glacial debris were surrounded by the sea. Stretching out into the Atlantic like a giant fish, the island continues to change.

Thousands of years later, water still re-sculpts the island’s shoreline.

On October 17, 2016, the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 captured this image of Long Island’s East End.

While the North Shore is characterized by craggy inlets and peninsulas, the South Shore is lined with smooth, protective sand bars—the result of constantly pounding waves.

Between the branching tails of the East End lies Gardiners Island, which spans more than 3,300 acres and is closed to the public—a source of curiosity given its proximity to population-dense Long Island.

In the 1600s, Gardiners was believed to have a cache of pirate gold.

Modern scientists appreciate it for another form of booty: its rich coastal geology.

On the northern end of Gardiners Island (above), a fang-like feature juts into the water.

This cuspate foreland at Bostwick Point owes its shape to the waves.

As they hit the shore, waves agitate sediment along the coast.

When they break at an angle to the coast, this creates a current parallel to the coastline called a “longshore current.”

Combined, these processes can rake sand and sediment into this triangular feature.

The opposite end of the island (below) includes a long, finger-shaped sand bank called a spit.

These sand features frequently form at the mouths of inlets and in places where water must move around coastal barriers and other features.

The spit projecting from the island’s southern end has grown by nearly a mile (1.6 kilometers) over the past few decades.

In the process, the ocean has breached its length at several points, creating smaller islets like Cartwright Island.

Long Island with the GeoGarage platform

Coastline breaches most often form during hurricanes, nor’easters, and other potent storms, said Andrew Ashton, a coastal geologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

However, over time, the constant pounding of waves tends to smooth out spits, refilling the gaps between them.

Strong currents tend to develop around such features.

In this image, the faint, light-colored streams of sediment in the water trace this movement.

The spit acts like a funnel, forcing water to move through a narrower channel and resulting in more powerful currents.

To get the same amount of water through the space, its flow must speed up, Ashton said.

“This little spit coming off the island is trying to choke that water off.”

Thursday, May 4, 2017

Albatrosses counted from space

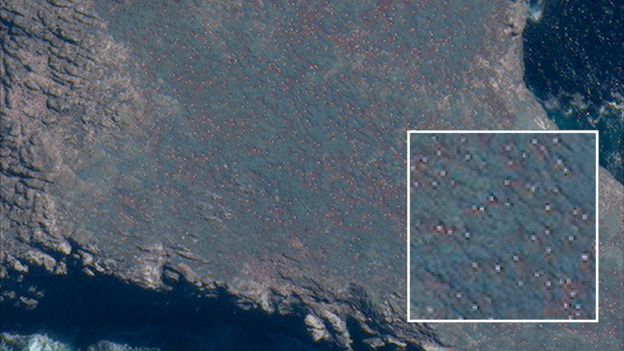

Craggy outcrop: At first glance there may not be much to look at...

From BBC by Jonathan Amos

Scientists have started counting individual birds from space.

They are using the highest-resolution satellite images available to gauge the numbers of Northern Royal albatrosses.

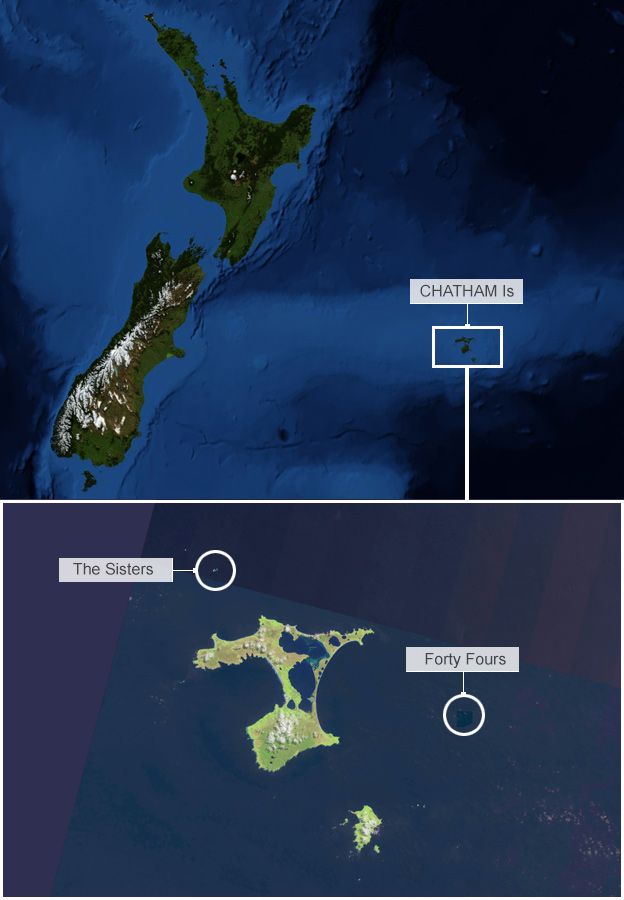

This endangered animal nests almost exclusively on some rocky sea-stacks close to New Zealand’s Chatham Islands.

The audit, led by experts at the British Antarctic Survey, represents the first time any species on Earth has had its entire global population assessed from orbit.

The scientists report the satellite technique in Ibis, a journal of the British Ornithologists' Union.

photo : Paul Scofield

Ordinarily, these birds are very difficult to appraise because their nesting sites are so inaccessible.

Not only are the sea-stacks far from NZ (680km), but their vertical cliffs mean that any visiting scientist might also have to be adept at rock climbing.

"Getting the people, ships or planes to these islands to count the birds is expensive, but it can be very dangerous as well," explained Dr Peter Fretwell from BAS.

This makes the DigitalGlobe WorldView-3 satellite something of a breakthrough.

It can acquire pictures of Earth that capture features as small as 30cm across.

The US government has only recently permitted such keen resolution to be distributed outside of the military and intelligence sectors.

WorldView-3 can see the nesting birds as they sit on eggs to incubate them or as they guard newly hatched chicks.

With a body length of over a metre, the adult albatrosses only show up as two or three pixels, but their white plumage makes them stand out against the surrounding vegetation.

The BAS team literally counts the dots.

Bird island, South Georgia with the GeoGarage platform (SHN nautical chart)

The researchers first checked their methodology at Bird Island, South Georgia.

This is a unique nature reserve in the South Atlantic where the nests of another species of great albatross, the Wandering albatross (Diomedea exulans), are individually marked with GPS locators.

The biggest confounding factor is large, light-coloured rocks.

But the analysis showed the team could get a very close match between the pixelated birds in the space images and the nests that were recorded in the ground-truth data.

There tends to be a slight over-counting, which the team puts down to breeding partners or non-breeding birds also being captured in a satellite scene.

Applying the technique at the Chatham Islands, the team counted just over 3,600 nests.

This is slightly down on a manual count of 5,700 that was made in 2009.

The birds favour sea-stacks known as The Sisters and the Forty Fours

Motuhara, Bertier or the Forty Fours island with the GeoGarage platform

(Linz nautical chart)

(Linz nautical chart)

Dr Fretwell said: "The breeding numbers we counted were much lower than we anticipated, which could show us that the population is declining or it could show just that we had a particularly poor year. But this illustrates why you have to do this over several years, and doing it by satellite is going be a lot cheaper and more efficient."

Dr Paul Scofield at Canterbury Museum, NZ, is a co-author on the Ibis paper.

He described the difficulty of counting the birds in the traditional way at the group of stacks known as the Forty Fours.

"The 44s are particularly tricky," he told BBC News. "I once waited a whole month on the main Chatham Island for the weather to clear so I could land.

"Even if you use a plane, it's a problem as planes are only available infrequently and the wind and cloud prevent flying. Then if you take photos, you have to count them. That can take 100s of hours. This technology still requires the satellite to be in the right place and no cloud but it is certainly cheaper and more reliable."

photo : Paul Scofield

Like the other five species of great albatross, Northern Royals are under pressure for a variety of reasons.

Commercial fishing has depleted the stocks on which these seabirds also feed, and the baited longline gear used by some vessels has an unpleasant knack for attracting foragers and pulling them underwater where they drown.

But the Northern Royals in particular are vulnerable because of their desire to nest only on the Chatham Islands sea-stacks.

If one big storm rolls through at the wrong time of year, it can severely dent breeding success.

"In 1986, a huge storm washed waves over these 50m-tall islands," said Dr Scofield.

photo : Paul Scofield

Links :

Wednesday, May 3, 2017

Meet the billionaire (and ex-fisherman) giving away his fortune to help save the ocean

181-metre (594-foot) vessel to be launched in 2020.

Rokke controls several companies through his 66.7-percent stake in holding company Aker, including oil production group Aker BP, oil services group Aker Solutions, engineering group Kvaerner and biotech and fisheries group Aker Biomarine.

Video: Aker Biomarine

From Time by Rob Wile

A former-fisherman-turned-billionaire from Norway known for being a ruthless businessman now says he plans to give most of his wealth away.

Kjell Inge Roekke is the tenth-richest man in Norway, with a net worth over $2 billion.

In an interview with Oslo's Aftenposen newspaper published Tuesday, he revealed plans to bequeath his holdings in ways that can benefit society, starting with a state-of-the-art ship that will perform marine research.

"Sea covers 70 percent of Earth's surface and much is not researched," he said.

Among other things, Roekke's ship will remove up to five tons of plastic daily from the ocean and melt it down so it can do no harm.

The path to wealth for Roekke, 55, is a fascinating story.

He was born in a small town on Norway's west coast.

Suffering from dyslexia, he dropped out of high school and moved to Seattle to catch pollock and crab.

Thereafter, he developed what many in Norway describe as "American" traits that have both helped his business and earned him a controversial reputation.

He built his fortune by buying up old boats and modifying them into industrial trawlers.

He returned to Norway in his late '30s and set about acquiring a stake in a 173-year-old Norwegian conglomerate, buying up 40 percent of its shares and merging it with his own Resources Group International.

Forbes reported that Roekke has "earned a reputation as a ruthless corporate raider" throughout his career.

"He was the first one to bring American-style, aggressive capitalism to Norway, daring to use shareholder power to get what he wanted," Steinar Dyrnes, a journalist at the Aftenposten who wrote a biography of Roekke, told Reuters in 2014.

The research ship will carry 30 crew members and 60 scientists

photo : TRG

Roekke is also known for having an explosive temper.

"He is often very charming and friendly," Dyrnes said of Roekke.

"But there is another side. He can be very angry ... which is very un-Norwegian."

Indeed, Roekke spent 23 days in prison after being convicted of bribing his way to a boating license. Afterward, he spent more than $3,000 buying takeout pizzas for his old cellmates.

That generosity has now appeared to have gotten the better of Roekke.

"I want to give back to society the bulk of what I've earned," he told Aftenposten.

"This ship is a part of it. The idea of such a ship has evolved over many years."

Among other things, the ship will be used to conduct research on plastics in the ocean.

photo : TRG

The cost of the ship was not disclosed, but it will include everything from sea and air drones to an auditorium to enormous amounts of lab space.

It will be managed by conservation organization WWF, and be known as REV, short for research expedition vessel.

One of its primary focuses will be how to control the enormous amount of plastic now at sea.

Roekke, who also owns an oil business, has given WWF complete independence as for its mission.

"We are far apart in their views on oil, and we will continue to challenge Røkke when we disagree with him," WFF chief Nina Jensen told Aftenposten, "but in this project we will meet to collectively make a big difference in the environmental struggle."

Links :

Tuesday, May 2, 2017

China’s appetite pushes fisheries to the brink

Vendors and wives of fishermen waiting for boats to return to Joal, Senegal.

Credit Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

From NYTimes by Andrew Jacobs

JOAL,

Senegal — Once upon a time, the seas teemed with mackerel, squid and

sardines, and life was good. But now, on opposite sides of the globe,

sun-creased fishermen lament as they reel in their nearly empty nets.

“Your net would be so full of fish, you could barely heave it onto the boat,” said Mamadou So, 52, a fisherman in Senegal, gesturing to the meager assortment of tiny fish flapping in his wooden canoe.

A world away in eastern China,

Zhu Delong, 75, also shook his head as his net dredged up a

disappointing array of pinkie-size shrimp and fledgling yellow croakers.

“When I was a kid, you could cast a line out your back door and hook

huge yellow croakers,” he said. “Now the sea is empty.”

Overfishing

is depleting oceans across the globe, with 90 percent of the world’s

fisheries fully exploited or facing collapse, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization.

From Russian king crab fishermen in the west Bering Sea to Mexican ships

that poach red snapper off the coast of Florida, unsustainable fishing

practices threaten the well-being of millions of people in the

developing world who depend on the sea for income and food, experts say.

Senegalese fishermen with their meager catch.

Credit Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

But China, with its enormous population, growing wealth to buy seafood

and the world’s largest fleet of deep-sea fishing vessels, is having an

outsize impact on the globe’s oceans.

Having depleted the seas close to home, Chinese fishermen are sailing farther

to exploit the waters of other countries, their journeys often

subsidized by a government more concerned with domestic unemployment and

food security than the health of the world’s oceans and the countries

that depend on them.

Increasingly, China’s growing armada

of distant-water fishing vessels is heading to the waters of West

Africa, drawn by corruption and weak enforcement by local governments.

West Africa, experts say, now provides the vast majority of the fish

caught by China’s distant-water fleet.

And by some estimates, as many as two-thirds of those boats engage in fishing that contravenes international or national laws.

China’s

distant-water fishing fleet has grown to nearly 2,600 vessels (the

United States has fewer than one-tenth as many), with 400 boats coming

into service between 2014 and 2016 alone.

Most of the Chinese ships are

so large that they scoop up as many fish in one week as Senegalese boats

catch in a year, costing West African economies $2 billion a year,

according to a new study published by the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

Part of China’s enormous fishing fleet at the harbor in Zhejiang, China.Credit Gilles Sabrie for The New York Times

Many of the Chinese boat owners rely on government money

to build vessels and fuel their journeys to Senegal, a monthlong trip

from crowded ports in China.

Over all, government subsidies to the

fishing industry reached nearly $22 billion between 2011 and 2015,

nearly triple the amount spent during the previous four years, according

to Zhang Hongzhou, a research fellow at Nanyang Technological

University in Singapore.

That figure, he said, does not include the tens of millions in subsidies and tax breaks that coastal Chinese cities and provinces provide to support local fishing companies.

According to one study by Greenpeace,

subsidies for some Chinese fishing companies amount to a significant

portion of their income. For one large state-owned company, CNFC

Overseas Fisheries, the $12 million diesel subsidy it received last year

made the difference between profit and loss, according to a corporate

filing.

“Chinese

fleets are all over the world now, and without these subsidies, the

industry just wouldn’t be sustainable,” said Li Shuo, a global policy

adviser at Greenpeace East Asia. “For Senegal and other countries of

West Africa, the impact has been devastating.”

In

Senegal, an impoverished nation of 14 million, fishing stocks are

plummeting. Local fishermen working out of hand-hewn canoes compete with

megatrawlers whose mile-long nets sweep up virtually every living

thing. Most of the fish they catch is sent abroad, with a lot ending up

as fishmeal fodder for chickens and pigs in the United States and Europe.

Mor Mbengul was taught how to fish by his grandfather.

But unlike his forefathers, he can no longer live from his catch.

International trawlers have all but depleted Senegal's fish reserves.

Many foreign fishing fleets refuse to stick to quotas.

The sea’s diminishing returns mean plummeting incomes for fishermen and higher food prices for Senegalese citizens, most of whom depend on fish as their primary source of protein.

“We

are facing an unprecedented crisis,” said Alassane Samba, a former

director of Senegal’s oceanic research institute. “If things keep going

the way they are, people will have to eat jellyfish to survive.”

When it comes to global fishing operations,

China is the indisputable king of the sea. It is the world’s biggest

seafood exporter, and its population accounts for more than a third of

all fish consumption worldwide, a figure growing by 6 percent a year.

China has depleted the seas close to home.

Credit Gilles Sabrie for The New York Times

The

nation’s fishing industry employs more than 14 million people, up from

five million in 1979, with 30 million others relying on fish for their

livelihood.

“The

truth is, traditional fishing grounds in Chinese waters exist in name

only,” said Mr. Zhang of Nanyang University.

“For China’s leaders, ensuring a steady supply of aquatic products is not just about good economics but social stability and political legitimacy.”

“For China’s leaders, ensuring a steady supply of aquatic products is not just about good economics but social stability and political legitimacy.”

But as they press toward other countries, Chinese fishermen have become entangled in a growing number of maritime disputes.

Indonesia has impounded scores of Chinese boats caught poaching in its waters, and in March last year, the Argentine authorities sank a Chinese vessel that tried to ram a coast guard boat. Violent clashes between Chinese fishermen and the South Korean authorities have left a half-dozen people dead.

For Beijing, the nation’s fleet of fishing vessels has helped assert its territorial ambitions in the South China Sea.

In Hainan Province, the government encourages boat owners to fish in

and around the Spratlys, the archipelago claimed by the Philippines, and

the Paracel Islands, which Vietnam considers its own.

A Filipino fishing boat that had been chased away from Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea by a Chinese Coast Guard vessel last year.

Credit Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

This maritime militia

receives subsidized fuel, ice and navigational devices. Backed by the

firepower of Chinese naval frigates, they have driven away thousands of

Filipino fishermen who depended on the rich waters around the Spratly

Islands.

Across the Philippine province of Palawan, the impact is reflected in the rows of idled outriggers and the clouds of smoke drifting across freshly denuded hillsides.

Unable to live off the sea, desperate fishermen

have been burning protected coastal jungle to make way for rice fields.

But heavy rain often washes away the topsoil, environmentalists say,

rendering the steep land useless.

“Young boys spend their lives preparing to become fishermen,” said Eddie Agamos Brock, who runs Tao, an ecotourism initiative.

“Now they have no way to make a living from the sea.”

Fishermen in an outrigger in front of a fire for slash-and-burn agriculture on Darocotan Island in the Philippines.

Credit : Katherine Jack

For Senegal, which stretches along the Atlantic for more than 300 miles,

the ocean is the economic lifeblood and a part of the national

identity. Seafood is the main export, and fishing-related industries

employ nearly 20 percent of the work force, according to the World Bank.

Ceebu

jen, a hearty fish stew, is the national dish, and sawfish — once

plentiful but now rare — grace bank notes. No Senegalese postcard is

complete without an image of pirogues, the exuberantly painted boats

fishermen use.

Despite declining fish stocks, unrelenting drought linked to climate change has driven millions of rural Senegalese to the coast, increasing the nation’s dependence on the sea.

With two-thirds of the population under 18, the strain has helped fuel the surge of young Senegalese trying to reach Europe.

“Foreigners

complain about Africa migrants coming to their countries, but they have

no problem coming to our waters and stealing all our fish,” said

Moustapha Balde, 22, whose teenage cousin drowned after his boat sank in

the Mediterranean.

The migration to the coast has transformed this seaside city, Joal, from a palm-shaded fishing village into a town of 55,000. Abdou Karim Sall,

50, president of the local fishermen’s association, said there were now

4,900 pirogues in Joal, up from a few dozen when he was a teenager.

“We

always thought that sea life was boundless,” he said while patrolling

the coastline. Now, he added, “we are facing a catastrophe.”

Fishermen pulling in nets off the coast of Joal, Senegal.

Credit Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

Mr.

Sall became a local hero after he single-handedly detained the captains

of two Chinese boats that were fishing illegally.

These days, residents

curse him under their breath because he has expanded his campaign

against overfishing to include Senegalese boats that flout fishing rules

designed to help stocks rebound.

“I understand why they hate me,” he said.

“They are just trying to survive from day to day.”

Still,

most of his ire is directed at the capacious foreign-owned trawlers.

These days, more than 100 large boats work Senegalese waters, a mix of

European, Asian and locally flagged vessels, according to government

figures.

That number doesn’t include boats that fly Senegalese flags but

are owned by Chinese companies.

Also uncounted are the ships that fish illegally, often at night or on

the fringes of Senegal’s 200-mile-wide exclusive economic zone — well

out of reach of the country’s small navy.

Dyhia Belhabib,

a fisheries expert trying to quantify illegal fishing along the African

coast, said Chinese boats were among the worst offenders; in West

Africa, they report just 8 percent of their catch, compared with 29 percent for European-flagged vessels, she said.

According

to her estimates, Chinese boats steal 40,000 tons of fish a year from

Senegalese waters, an amount worth roughly $28 million.

Her figures do not include boats engaged in illegal fishing

that were never caught — nearly two-thirds of all Chinese vessels, she

said. “When darkness falls, the dynamics of illegal fishing change

dramatically and it becomes a free-for-all.”

The

problem is magnified across West Africa. Some countries, like

Guinea-Bissau and Sierra Leone, have just a handful of boats to police

their national waters.

Men making new fishing nets on the streets of Joal.Credit Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

In

Senegal, recent legislation has drastically increased fines for illegal

fishing to $1 million, and officials pointed to the two impounded

foreign-owned boats in Dakar, the nation’s capital, as proof that their

efforts are bearing fruit.

Glancing out at the sea, Capt. Mamadou Ndiaye described the challenges he faces as the director of enforcement for Senegal’s Ministry of Fisheries and Maritime Economy.

Many scofflaws, he noted, fish on the edge of Senegal’s territorial waters and can easily escape when threatened.

His

agency cannot afford speedboats or satellite imagery; it could also use

a functioning airplane. “Still, we have more than many other countries,

and we have to help them, too,” he said.

Most

of the small pelagic fish that swim in Senegalese waters — and make up

85 percent of the nation’s protein consumption — migrate in enormous

schools between Morocco and Sierra Leone. Along the way, they are

scooped up by hundreds of industrial trawlers, at least half of them

Chinese-owned, experts say.

In

2012, Senegal stopped granting licenses to foreign trawlers for these

small fish, but neighboring countries have refused to follow suit.

Mauritania, where most of the fleet is Chinese-Mauritanian joint

ventures, is home to 20 fishmeal factories that grind sea life into exported animal feed, with another 20 planned, according to Greenpeace.

Protecting the seas sometimes means saying no to China, whose largess is funding infrastructure across Africa.

“It’s

hard to say no to China when they are building your roads,” said Dr.

Samba, the former head of Senegal’s oceanic research institute.

Then there is the lack of transparency that keeps national fishing agreements with China secret.

“There is corruption in opacity,” said Rashid Sumaila,

director of the Fisheries Economics Research Unit at the University of

British Columbia Fisheries Center.

“Sometimes the Chinese pay bribes to

get access and that money doesn’t trickle down, so the population is hit

by a double whammy.”

Beijing has become sensitive to accusations that its huge fishing fleet is helping push fish stocks to the brink of collapse.

The

government says it is aggressively reducing fuel subsidies — by 2019

they will have been cut by 60 percent, according to a fishery official — and

pending legislation would require all distant-water vessels

manufactured in China to register with the government, enabling better

monitoring.

“The

era of fishing any way you want, wherever you want, has passed,” Liu

Xinzhong, deputy general director of the Bureau of Fisheries in Beijing,

said.

“We now need to fish by the rules.”

But

criticism of China’s fishing practices, he added, is sometimes

exaggerated, arguing that Chinese vessels traveling to Africa were

simply responding to the demand for seafood from developed countries,

which have been reducing their own fleets.

“People come to me and ask, ‘If China doesn’t fish, where would Americans get their fish to eat?’” he said.

Women selling fish at the street market in Joal.

Credit Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

Here

in Joal, the dwindling catches have prompted the closing of three of

the town’s ice factories, with the fourth barely holding on.

On the

town’s main quay, where women wade into the surf to meet arriving

pirogues, the competition for fish has become intense.

“We

used to have big grouper and tuna, but now we are fighting over a few

sardinella,” said one buyer, Sénte Camara, 68. On a good day, she makes

$20; on a bad day, she loses money.

“The future is dark,” she said.

To

catch anything, fishermen have to venture out farther, putting their

lives at risk if an engine stalls or a late summer storm barrels

through.

Sometimes the danger is a super trawler whose wake can easily

swamp a pirogue.

Five hundred women in Joal work full time salting, grilling and drying mackerel, anchovy and sardinella.

Credit Sergey Ponomarev for The New York Times

At

Joal’s vast outdoor smoking center, the lack of fish was apparent in

the empty racks normally stacked with yellow-tailed sardinella and

millet stalks smoldering below.

Daba Mbaye, 49, one of the few people working, said the smokers could no longer compete with the fishmeal factories.

“They

leave us with nothing, and we are powerless to stop them,” Ms. Mbaye

said.

“Now we are forced to catch juvenile fish, which is like going

into a house and killing all the children. If you do that, the family

will eventually disappear.”

Links :

Links :

- Quartz : China has fished itself out of its own waters, so Chinese fishermen are now sticking their rods in other nations’ seas

- Wired : Inside China’s Almost-Totally-Legal $400M Fishery in Africa

- The Diplomat : China and Africa's Illegal Fishing Problem

- The Guardian : Thousands of Chinese ships trawl the world, so how can we stop ...

- GeoGarage blog : Tackling illegal fishing in western Africa could create ... / West African fishing communities drive off 'pirate' fishing ... / Satellites and seafood: China keeps fishing fleet ... / China's empty oceans / China's fishermen explain why they think the sea is theirs

Monday, May 1, 2017

Why we need to research strange underwater creatures

This fascinating talk poses the question: is the way science approaches

life’s biggest mysteries restricting our ability to solve them?

Life on this planet is the history of rule breakers – species that didn't get the memo about how they were supposed to behave.

Life on this planet is the history of rule breakers – species that didn't get the memo about how they were supposed to behave.

So if we are

studying rule breakers, then shouldn't how we study them break the

rules, too?

Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado is a researcher at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Dr. Sánchez Alvarado's current research efforts are aimed at understanding the molecular and cellular basis of animal regeneration.

Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado is a researcher at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Dr. Sánchez Alvarado's current research efforts are aimed at understanding the molecular and cellular basis of animal regeneration.

From TexInnovations by Hailey Reissman

Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado is an advocate for underwater creatures with behaviors almost too weird to believe.

The sea is full of strange, little-understood creatures, says researcher

Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado at TEDxKC

(Collage: Alejandro Sánchez

Alvarado)

A tunicate called Thalia democratica asexually births its offspring from its “head”

(Video: Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado)

This 95% could be the key to cures for currently incurable diseases, better understanding of our genetic history, expansions to our tree of life, if only people believed in the value of this exploration, Alvarado says.

“We are measuring an astonishingly narrow sliver of life and hoping that those numbers will save all our lives [by propelling research],” he says.

“What is even more tragic is that [many underwater creatures'] biology remains sorely understudied,” Alvarado says. For example — the Schmidtea mediterranea, a type of flatworm that is common in coastal areas around the Mediterranean can regenerate itself after being chopped up into parts, yet it isn’t a household name or hot button topic in science.

“You can grab one of these animals and cut them into 18 different fragments and each and every one of those fragments will go on to regenerate a complete animal in under two weeks,” he says.

“18 heads, 18 bodies, 18 mysteries.”

The regeneration process of a Schmidtea mediterranea

(Photos: Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado / Jochen Rink)

“For the past decade and a half or so I’ve been trying to figure out how

these little dudes do what they do and how they pull this magic trick

off, but like all good magicians they’re not really releasing their

secrets,” Alvarado says.

More bizarre animals loved by Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado

(Collage: Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado)

Sunday, April 30, 2017

Rare sperm whale encounter with ROV

At 598 meters (1,962 ft) below the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of Louisiana,

ROV Hercules (EV Nautilus) encountered a magnificent sperm whale.

ROV Hercules (EV Nautilus) encountered a magnificent sperm whale.

The whale circled Hercules several times and gave our cameras the chance to capture some incredible footage of this beautiful creature.

Encounters between sperm whales and ROVs are incredibly rare.