Saturday, July 16, 2016

Friday, July 15, 2016

Underwater microscope provides new views of ocean-floor sea creatures in their natural setting

A new microscopic imaging system is revealing a never-before-seen view of the underwater world. Researchers from Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego have designed and built a diver-operated underwater microscope to study millimeter-scale processes as they occur naturally on the seafloor.

The Homo sapiens view of our world is all a matter of perspective, and we need to remember that we’re among the larger creatures on Earth.

At around 1.7 meters in length, we’re much closer in size to the biggest animals that have ever lived – 30-meter-long blue whales – than the viruses and bacteria that are less than one-millionth our size.

Our relative size and their invisibility to our naked eye makes it easy to forget that there are vastly more of those little guys than us – not just in number, but also in mass and volume.

And they’re vital to the health of our planet.

For example, every other breath of oxygen you take is courtesy of the photosynthetic bacteria that live in the ocean.

As early microscope pioneer Antony Van Lewenhook discovered approximately 350 years ago, these little “animalcules” are in almost every nook and cranny you can think of on Earth.

But until now, we haven’t been able to study most microscopic forms of ocean life in their native marine habitats at sufficient resolution to discern many of their miniature features.

This is important, as there are thousands of different millimeter-sized underwater creatures we previously couldn’t study unless they were removed and brought to the lab.

BUM has a high magnification lens surrounded by focused LED lights and a companion computer with ceramic buttons. Andrew D. Mullen/UCSD

Our new Benthic Underwater Microscope (BUM) changes that.

In building our underwater microscopes, we are inspired by oceanographer Victor Smetacek’s question of whether an in situ computerized telemicroscope could “do for microbial ecology what Galileo’s telescope did for astronomy.”

Simply put, we hope so. Underwater microscopy can help scientists tackle research questions in new ways.

Using the BUM, we’ve already seen some amazing new coral behaviors.

A glimpse of what we’ve been missing: Pocillopora polyps: a 2.8 x 2.4 mm field of view.

Andrew D. Mullen/UCSD

When researchers bring marine samples back to the lab, it’s impossible to exactly mimic the environment they came from – what we observe might not perfectly reflect creatures' real lives. Better, then, to bring the lab to the ocean.

For nearly five years now, our group has been tackling the technical challenges of underwater microscopy with the goal of recording images of marine life at these miniature scales.

We aim to explore microscopic life in a variety of natural settings via underwater imaging and video systems.

Previously, there was no technology available to see these tiny things from several centimeters away. The distance is important because we needed to put our components in a waterproof bottle and look out through an underwater port – placing us a bit away from our subjects.

Fortunately, with the commercial appearance of our hoped-for “long working distance” lenses, miniature cameras and efficient LED lights, we were able to assemble several underwater microscopes.

There were some technical challenges to overcome.

We had to figure out how to illuminate a very tiny area while simultaneously focusing a lens on precisely the same spot.

We also weren’t sure we could achieve the mechanical stability necessary to keep our system still enough to get great images.

And it was also paramount for a diver to be able to control the system via a computer interface.

Have BUM, will travel.

Emily L. A. Kelly/UCSD

After 18 months of work, we’d invented the first underwater microscope that a diver could carry into the field and use to take pictures of seafloor inhabitants at nearly micrometer resolution.

Our instrument allows us to clearly see features as small as one-hundredth of a millimeter underwater. An additional feature, a squishy electrically tunable lens, gives us the ability to rapidly focus on the objects that we are imaging.

This allows us to capture all parts of an object with substantial three-dimensional relief in focus.

The final system consists of two housings: one for the camera, lights and the lenses, the other for a computer controlling the camera along with a live diver interface and data storage.

After we finished testing the instrument in California, we traveled to Eilat, the southernmost city in Israel, to work with colleagues at the Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences.

With their help, we set up our system in the Red Sea’s well-preserved coral reefs.

In deploying the instrument, we use an undersea tripod to position the camera housing while resting the computer housing on the seafloor.

We then control the system’s parameters through a series of computer screens that culminate in recording the scene.

A newly visible underwater world

On our test dives, we saw with unprecedented detail a strange behavior of coral polyps, the tiny individual animals that make up a coral colony.

In a never-before-seen action, the polyps periodically embraced their neighbors, potentially to share food, in what we called polyp kissing.

In situ time series video of interaction between the coral Platygyra and four different stimuli.

In each frame Platygyra is on the left: top-left Galaxea, top right Stylophora, bottom left mesh net filled with Artemia, and bottom right another colony of Platygyra.

Images were captured at night with red light at a frame rate of 1 FPS. The playback is at a speed that is 480 times faster.

(Courtesy Andrew D. Mullen/UCSD)

We were surprised to see that at the same proximity, corals of the same species were at peace.

This is shown in the lower right corner of the video – the two Platygyra corals are not fighting.

The polyp communities that share connective tissue work together to ward off predators.

They’re not hostile to other colonies of their own species.

But when confronted with foreigners, or when aiming to expand their territory, they can extrude their digestive organs and rub a digestive enzyme all over the bodies of their enemies, as seen in the videos.

We hypothesize, as others have, that some set of chemicals they emit mediates the corals' awareness of each other.

The BUM was able to document algae

beginning to colonize the surface of bleached corals that were still

alive. 2.82 x 2.36 mm field-of-view.

Andrew D. Mullen/UCSD

For the first time in a natural setting, we examined how algae colonize and overgrow bleached corals at the microscale.

Where to focus in the future

Now that we have this new instrument, hopefully it will open up a whole new realm of scientific inquiry.

We imagine researchers will be eager to point the underwater microscope at kelp forests, rocky reefs, sea grass beds and mangroves.

For instance, we’re interested in exploring how kelp propagate as microscopic baby kelp seeds land on rocky areas of the seafloor.

Their success and density is important for understanding how kelp forests emerge.

And there are plenty of other questions about coral reefs that the BUM could help investigate.

How do coral diseases progress?

What happens on a microscopic level when coral polyps bleach?

How do corals deal with sedimentation and shed sand?

How do coral larvae grow and how are they recruited by a colony?

How do corals and algae compete?

With the new ability to see and record these processes happening in real-time in the ocean, researchers could make some interesting new discoveries.

As such, we have made our systems available to the scientific community – we plan to aid researchers by traveling to their work sites and taking photos and videos.

And we’re always thinking about further improvements – developing a next generation of underwater instruments that have higher frame rates and even better resolution.

In addition, there is one enchanting frontier to think about: underwater microscopic virtual reality – an immersive new way for scientists and everyone else to explore the wonders of the oceans.

Links :

Thursday, July 14, 2016

Mining Gold

West Australian coastline exploration on the first day of the Southern Hemisphere winter.

Wednesday, July 13, 2016

What the South China Sea ruling means for the world

The Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague ruled that China does not have historic rights to justify its expansive claims.

The verdict, which strongly favored the Philippines, will undermine China's claim to sovereignty under the nine-dash line it draws around most of the sea.

(Simon Denyer, Jason Aldag/The Washington Post / Satellite photos courtesy of CSIS)

(Simon Denyer, Jason Aldag/The Washington Post / Satellite photos courtesy of CSIS)

From The Washington Post by Ishaan Tharoor

A verdict delivered by an international court in the Hague sent geopolitical shock waves through Asia.

The panel of judges at the Permanent Court of Arbitration said that China's exclusive claims to a vast swath of territory in the South China Sea had no historical or legal basis, siding with the Philippines in a case that Manila had brought to the court in 2013 over China's expansive moves into a number of disputed islands and shoals.

The South China Sea is one of the world's most strategic bodies of water and remains a vital conduit for a huge proportion of global shipping.

But it's also now perhaps the most treacherous flash point in the world, with the overlapping claims of half a dozen Asian governments constantly creating regional friction.

In recent times, separate disputes between China and the Philippines and Vietnam have led to minor skirmishes and naval standoffs.

China, as The Washington Post has documented over the past year, has steadily sought to change the facts on the ground (or on the waves) in its favor, establishing military bases and building up new islands in areas under its control.

The United States, meanwhile, recently deployed aircraft carriers to the region, a somewhat striking move.

The Chinese have long claimed vrtually the whole entirety of the South China Sea and the barren rocks and islands within it as their sovereign territory.

The court, though, ruled against the legitimacy of China's "nine-dash line" -- marked in the map below -- which Beijing routinely invokes as the demarcation of its historical claim over the sea.

It's a decision that's already been widely rejected both by Chinese officials and local media, as my colleagues noted Tuesday morning.

"There is no single explanation for why asserting its authority over the South China Sea now matters so much to China," wrote Howard French, a veteran China hand, in a lengthy report in the Guardian last year.

Of course, Beijing has a clear interest in extending its control over the region's fisheries as well as the potentially vast deposits of natural gas and other resources beneath the ocean floor.

But, as French elaborates, it's about much more than that for China:

It is in part a matter of increasing the country’s sense of security, by dominating the maritime approaches to its long coast, and securing sea lanes to the open Pacific.

It is in part a matter of overcoming historical grievances.

And finally, it is about becoming a power at least on par with the US: a goal that Chinese leaders are themselves somewhat coy about, but which is now increasingly entering the public discourse.

Chart of the week : Mounting tension on the high seas

(click to enlarge)

Because of the South China Sea's symbolic and strategic importance to China, the tribunal's verdict is a stinging rebuke.

In fairness, Beijing was readying for this perceived loss of face.

Before this week, its officials indicated that they did not recognize the jurisdiction of the court.

Not long after news broke of the ruling, which is non-binding, Chinese state media declared it "null and void."

But the decision does return a great deal of scrutiny of China's actions in the South China Sea, which are being closely watched by the international community.

"'Might makes right' does not define international rules," a columnist trumpeted in the Philippine Star in the aftermath of the court's verdict.

"It is difficult to imagine how even the most slavish apologist for Beijing ... can possibly defend China’s claims, and more importantly its actions, in the South China Sea following the court’s devastating ruling," wrote Greg Sheridan, foreign editor of the Australian newspaper.

"China is now faced with a dilemma," wrote Simon Denyer and Emily Rauhala, The Washington Post's correspondents in Beijing.

"It can signal its displeasure at the ruling by extending that program and militarizing the islands it controls, risking confrontation and even conflict with emboldened Asian neighbors and the United States. Or it can suspend the program and adopt a more conciliatory approach, at the risk of a loss of face domestically."

The United States hopes the ruling and pressure blunt China's perceived expansionism in the Asia-Pacific and calms tensions with its neighbors.

“In the aftermath of this important decision, we urge all claimants to avoid provocative statements or actions,” said State Department spokesman John Kirby.

“This decision can and should serve as a new opportunity to renew efforts to address maritime disputes peacefully.”

But there's an argument that a stung Beijing may decide to be less cooperative with Manila and a new president who is hoping to secure vital trade deals with China.

"The Philippines may have won a favorable award ... but that leaves the space for bilateral negotiation and 'off ramping' with China limited," Ankit Panda observes in the Diplomat.

And at least one senior Chinese official seemed to signal a gloomy change in the atmosphere.

"It will certainly undermine and weaken the motivation of states to engage in negotiations and consultations for solving their disputes," Cui Tiankai, China's envoy in Washington, told Reuters after the decision from The Hague.

"It will certainly intensify conflict and even confrontation."

We'll see whether that's the case in the coming months.

When it comes to the South China Sea, though, the United States and China have competing visions for the future.

"What is at stake is not only regional security in Asia, which has been heavily undermined by the increased militarization of territorial disputes, but also shared access to global commons in accordance to modern international law," Richard Javad Heydarian, a Manila-based political scientist, wrote for Brookings.

"It is a clash between China’s 'territorial' and 'closed seas' vision of adjacent waters, on one hand, and the international community’s call for 'open seas' and rule of law in international waters, on the other."

But although it has the backing of a host of regional allies wary of China's rise and growing military, the United States doesn't have that much moral high ground in the matter, as my colleague Michael Birnbaum points out.

Major western powers, especially administrations in Washington, have kept themselves at arm's length from arbiters in The Hague.

"Many nations, including Russia, the United States and Britain, have disregarded international rulings at some point," Birnbaum wrote.

"And, unlike China, the United States has not even ratified the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, which underpinned Tuesday's ruling, so Washington could not be held accountable in a similar way."

Links :

- WashingtonPost : 5 stories you need to read to understand the South China Sea dispute / Chinese state media melts down over South China Sea ruling

- The Guardian : China attacks international court after South China Sea ruling

- WSJ : China Tries to Refocus South China Sea Dispute on Rocks and Reefs

- CSIS : Judgment Day : The South China Sea Tribunal issues its ruling

Tuesday, July 12, 2016

Philippines vs China: Why a South China Sea ruling may change Asia

- A UN court will decide which countries can exploit the resources of the South China Sea

- China has refused to participate in the arbitration case

In 2013, the Philippines filed a case against China at the Permanent Court of Arbitration

in The Hague, seeking a ruling on its right to exploit the waters near

the islands and reefs it occupies in the South China Sea.

Beijing

has refused to participate in the case but the outcome could have

lasting implications for China's rise as a superpower, global trade and

even world peace.

China is conducting military drills in the disputed waters in the run-up to the ruling, which will be released on July 12.

What's the Philippines case?

There are three key points -- firstly, the Philippines wants the court to decide whether certain features in the sea are islands, reefs, low tide elevations or submerged banks.

It

might sound like a minor point, but under the United Nation's

Convention on Laws of the Sea (UNCLOS) each delivers different rights

over the surrounding waters.

For

example, a recognized island delivers an Exclusive Economic Zone of 200

nautical miles, giving the responsible country complete control over all

enclosed resources, including fish, oil and gas.

Importantly, artificial islands like those China has been building are not counted.

Secondly, the Philippines wants the

court to rule on exactly what territorial claims in the South China Sea

their country is owed under UNCLOS.

These may contradict and

potentially legally invalidate China's claims.

Finally,

the Philippines wants the court to determine if China has infringed on

its territorial rights through China's construction and fishing

activities in the sea.

What is UNCLOS?

Will the ruling resolve anything?

Legally, the Permanent Court of Arbitration's decision will be binding and there may be implications diplomatically for China if they refuse to abide by it.

Rare 1602 World Map from Matteo Ricci,

the First Map in Chinese to Show the Americas, Library of Congress

A portion of an original 1602 Ricci Map at the

University of Minnesota

that has the legend about the Ming Empire’s

borders erased.

Photo courtesy of John J. Tkacik

Unattributed, very detailed, two page colored edition (1604?), copy of the 1602 map Kunyu Wanguo Quantu by Matteo Ricci at the request of the Wanli Emperor.

This digitalization of the map is of a Japanese export copy of the original Chinese version, with phonetic annotations in Katakana for foreign place names outside of the Sinic world, predominantly around Europe, Russia and the Near East.

A portion of an 1604 version of the Ricci map

with the legend about the Ming Empire’s borders intact.

Photo courtesy of image Database of the Kano Collection, Tohoku University Library

Photo courtesy of image Database of the Kano Collection, Tohoku University Library

and Wikimedia Commons

What's China's stance?

China has long refused to take part in the case and, under the terms of the UNCLOS treaty, this is well within their legal right.

China has long refused to take part in the case and, under the terms of the UNCLOS treaty, this is well within their legal right.

As

the verdict gets closer, Beijing has spoken out, saying the case goes

beyond the jurisdiction of UNCLOS and insisting multiple times that it

won't acknowledge the court's decision.

Additionally, China has been ramping up a propaganda campaign to assert their historical rights in the region with state news agency Xinhua publishing almost daily articles outlining their views.

Still, the court's decision is widely expected to go against them.

"I

wouldn't say it is 100% but it's expected predominantly to go in the

Philippine's way," said Euan Graham, international security program

director at Australia's Lowy Institute.

"There

will be something for China but almost everyone I've spoken to would

expect the bulk of the Philippine's case to get a positive ruling."

What is UNCLOS?

The

United Nation's Convention on the Law of the Sea, originally agreed to

in 1982, was designed to allow countries to clearly lay out who

controlled what off their coastline.

For

the purposes of the South China Sea dispute, the most important part of

UNCLOS is the exact definitions of what each country controls.

An

island controlled by a country is entitled to a "territorial sea" of 12

nautical miles (22 kilometers) as well as an Exclusive Economic Zone

(EEZ) -- whose resources -- such as fish -- the country can exploit,

of up to 200 nautical miles (370 kilometres).

A

rock owned by a state will also generate a 12 nautical mile territorial

border but not an economic zone under UNCLOS, while a low-tide

elevation grants no territorial benefits at all.

These

obscure definitions are very important in the South China Sea and in

the Philippine's case to the United Nations, as Manila's UNCLOS-mandated

Exclusive Economic Zone overlaps with waters claimed by China and

Vietnam.

It also explains why countries are so desperate to grab islands and reefs in the South China Sea to legitimize their claims.

Both

China and the Philippines are signatories to the convention, as is

Vietnam, although several other countries aren't including the United

States.

An aerial photo taken on Sept. 25, 2015 from a seaplane of Hainan Maritime Safety Administration shows cruise vessel Haixun 1103 heading to the Yacheng 13-1 drilling rig during a patrol insouth China Sea.

(Xinhua/Zhao Yingquan)

Why does it matter?

The South China Sea is one of the most politically sensitive regions in the world - the Permanent Court of Arbitration's ruling will be the first time an international court has passed judgment on the region's mess of claims and counter-claims.

The South China Sea is one of the most politically sensitive regions in the world - the Permanent Court of Arbitration's ruling will be the first time an international court has passed judgment on the region's mess of claims and counter-claims.

At least five countries claim territory in the South China Sea, including China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and Brunei.

Several tense stand-offs have already threatened to throw the area into conflict, including in 2012 when the Philippine Navy intercepted several Chinese fishermen off the Scarborough Shoal.

As

China begins to stretch its muscles as a growing superpower, the South

China Sea has become a testing ground for whether they will rise as part

of the global society or outside it.

If

they ignore or go against the court's arbitration, analysts say it

could have worrying implications for the stability of the region and

weaken an already fragile peace in the sea.

The South China Sea is also a major trade corridor, with $5.3 trillion in ship-borne trade passing through the waters each year.

"The

best guesses suggest that more than half the world's maritime trade

goes through the Straits of Malacca, along with half the world's

liquefied natural gas and one third of its crude oil," southeast Asia

expert Bill Hayton wrote in this book The South China Sea: The Struggle

for Power in Asia.

South China Sea : a dangerous area

with the GeoGarage platform (NGA chart)

Will the ruling resolve anything?

Legally, the Permanent Court of Arbitration's decision will be binding and there may be implications diplomatically for China if they refuse to abide by it.

"People are saying if China

doesn't abide by the ruling then it undermines its own position that it

is committed to maintaining a rules-based order," Singapore's Institute

of South East Asian Studies senior fellow Ian Storey said.

"So the consequences will be to its reputation."

However,

there is no military options to enforce the ruling - United Nations

troops will not be forcing China off Fiery Cross or Mischief Reef.

"The big question mark about the ruling

is who is going to reinforce it, because ultimately it's a binding

judgment, but if China chooses to ignore it it's very difficult for the

Philippines to change the status quo," Lowy Institute's Graham said.

"I don't think anyone expects China to reverse its island building."

However,

legal experts have said if the ruling is favorable to them, the

Philippines could return to court and ask for other, stricter measures

against China.

It's also important

to note the tribunal has no jurisdiction to decide any issues over the

sovereignty of islands and rocks in the South China Sea -- the heart of

the controversy.

UNCLOS only deals with control of the waters

surrounding them.

Links :

- EastAsiaForum : Like it or not, UNCLOS arbitration is legally binding for China

- Quartz : China illegally cordoned off a huge part of the South China Sea for military drills—and will likely do so again

- Taipei : The Emperor’s Mysterious Map and the South China Sea

- Time : China Will Never Respect the U.S. Over the South China Sea. Here’s Why

- Inquirer : UNCLOS lays down the rules for the planet’s oceans

- BBC : Why is the South China Sea contentious?

- The Diplomat : After the South China Sea Arbitration, where do we go after the panel has spoken?

- Bloomberg : Decoding the Jargon of the South China Sea Dispute

- WarOnTheRocks : How will China react to the gavel coming down in the South China Sea ?

- GeoGarage blog : What China has been building in the South China Sea / What makes an island ? Land reclamation and the South China Sea arbitration / How China is building the biggest commercial-military empire in History

Monday, July 11, 2016

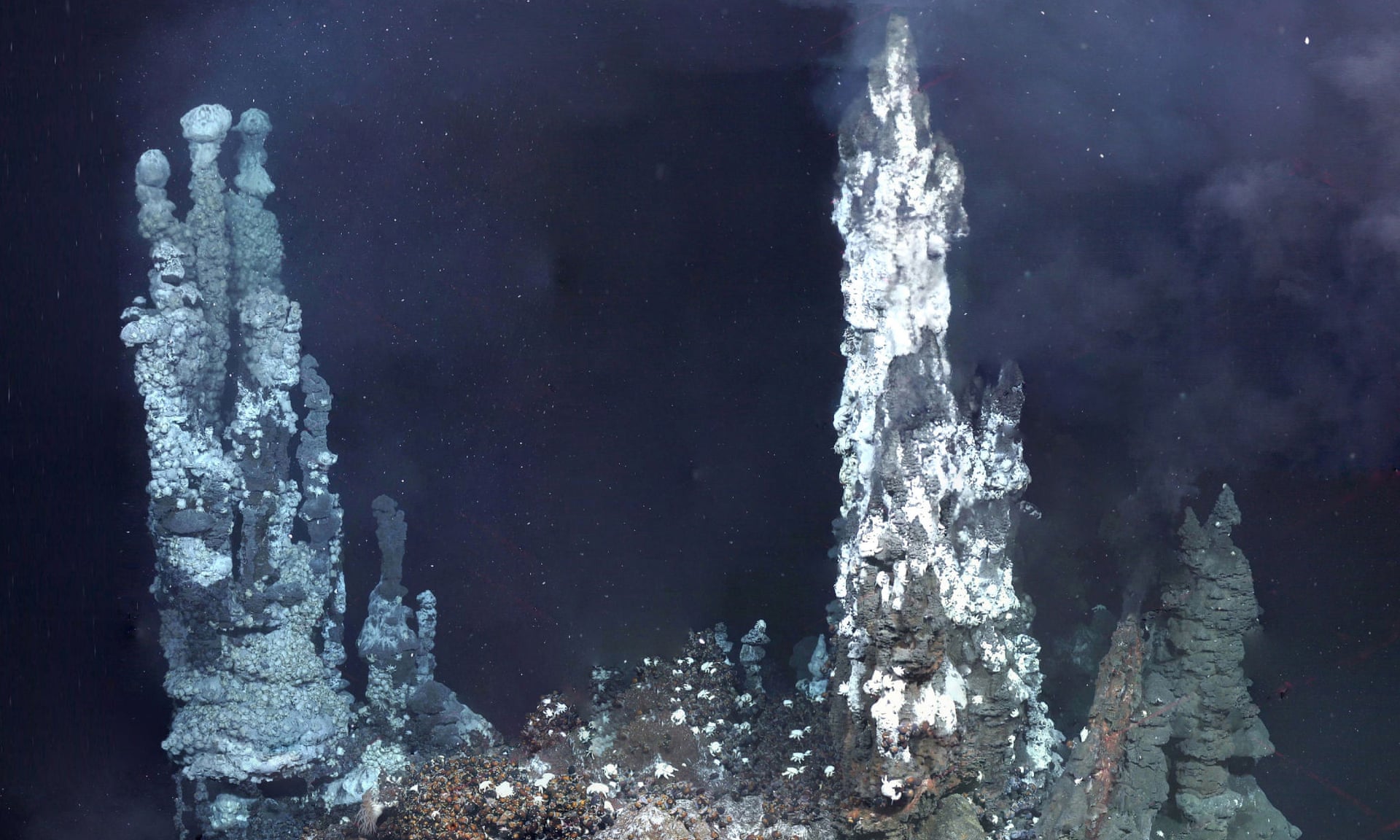

UK expedition explores potential and risks of deep sea gold rush

Footage from the deep hydrothermal vents in the Caribbean.

At sites like this, mineral deposits are formed, including gold and zinc.

HROV Nereus Dive 061 at the Von Damm hydrothermal vent field, Mid-Cayman Rise

courtesy of www.schmidtocean.org

From The Guardian by Damian Carrington

Huge rich-metal deposits on the ocean floor could transform the global commodities market but there are fears mining them could harm rare ecosystems

A scientific expedition has been launched from the UK to explore the mining of rich metal deposits on the deep ocean floor, which are the focus of a new gold rush around the world.

The UK research vessel, the RRS James Cook, left Southampton on Thursday, heading for the underwater ridge in the middle of the Atlantic where volcanic activity drives hot springs, also known as black smokers.

“They have left these incredibly metal-rich deposits as mounds on the sea bed, about the size of a big football stadium,” said Bramley Murton, from the UK’s National Oceanography Centre, who is leading the expedition.

“The aim is see whether they are a viable source of essential metals in the future, both in terms of economics and environmental sustainability.”

The metals are vital for many aspects of modern society, from smartphones to aircraft to green energy, but China has a virtual monopoly on many of them.

The scientists leading the expedition, which will deploy a giant metal detector, scanners and drills, says mining the deep sea resources could transform the global market.

Prime minister David Cameron has said such exploits could be worth £40bn to the UK alone and in March, a UK company won a second licence from the International Seabed Authority to prospect in 75,000 sq km of the Pacific.

There are fears that deep sea mining could harm the extraordinary creatures and ecosystems that live on the hot springs that deposit the metals.

But the new voyage will only examine hydrothermal vents that have been extinct for thousands of years and no longer host the unique vent ecosystems.

Formation of mineral rich chimneys on the Atlantic ocean floor, East Scotia Ridge.

Photograph: National Oceanographic Centre

They will use robot submarines to be the first to drill into extinct vent deposits, using a specially hardened drill to probe 55 metres below the sea bed.

“It is hovered over the sea bed at three to four metres and moved very slowly along,” said Murton.

More data will come from two instruments - called Daisy and Sputnik - that use electromagnetic waves to get a 3D image of the deposits, like a medical CT scan.

A key question is how much the seawater has rusted away the metals deposited by the hot springs that stopped flowing up to 50,000 years ago.

The deposits can be extremely rich in valuable metals, including gold, cobalt, zinc, tellurium and so-called “rare earths”, which are used in many electrical technologies, including smartphones, wind turbines, solar panels and electric cars and in high-strength, lightweight alloys used in aircraft, for example.

“These elements have all been identified as critical to our modern technology and the functioning of modern society,” said Murton.

The concentration of the metals is far greater than in ore rocks on land containing, for example, copper at 25-30%, compared to 2%.

The potential prize is great, said Murton: “The supply of rare earths is somewhat restricted at the moment, as 98% of the supply comes from China and they are very keen to maximise that scarce commodity for their own industry.

So there’s a kind of monopoly which makes it difficult for other countries.” Cobalt comes almost exclusively from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“There is overwhelming interest in the potential of these resources, which is why countries are really rushing to lay their claims,” Murton said.

Dozens of large areas have now been licensed in the open ocean, with the UK, Germany, France, Portugal, South Korea, Brazil, Russia and China among the nations involved, and almost all of the Atlantic ridge from the equator to the Arctic circle has been claimed in recent years.

“I think the technology capability [to mine] will be there in the next 5-10 years and I think there will be active commercial extraction in the same timeframe,” he said.

“I think it has the potential to be transformative for the commodities market.

It will have a significant impact on the global supply.” One Canadian firm, Nautilus Minerals, intends to start work on the sea bed near Papua New Guinea in 2018, although this may be delayed by funding difficulties.

The RRS James Cook expedition is part of a €15m (£12.5m) EU-funded research programme called Blue Mining, which also involves biologists and ecologists.

“They are tasked with really trying to understand what the environmental impact might be if these deposits are ever exploited commercially,” said Murton.

“There is absolutely no suggestion or enthusiasm from either scientists, or mining companies as far as I know, to go anywhere near the active hydrothermal systems,” said Murton.

“They are extraordinarily rich areas of unique species and ecosystems and we wouldn’t do anything to disturb those.”

Will McCallum, at Greenpeace UK, said: “The emerging threat of seabed mining is an urgent wake-up call for the need to protect the oceans.

The deep ocean is not yet mapped or explored and so the potential loss of fauna and biospheres from mining is not yet understood.

What we desperately need is a global network of ocean sanctuaries.”

Renowned ocean explorer Sylvia Earle is also concerned and said recently: “What are we sacrificing by looking at the deep sea with dollar signs on the few tangible materials that we know are there? We haven’t begun to truly explore the ocean before we have started aiming to exploit it.”

However, Murton said deep sea mining might be less environmentally destructive than mining on land.

“The deposits we are looking at sit on the seabed and are relatively easy to access.

In terms of disturbing the environment, the size of the whole, the amount of rock you have to move, crush up and throw away, it’s much smaller.

We wouldn’t have acid tailing pools like the one that burst in Brazil in 2015 or huge holes in the ground or forests that are cut down.”

The International Seabed Authority says its regulations give: “special emphasis to ensuring that the marine environment is protected from any harmful effects which may arise during mining activities, including exploration.”

Murton said the information from the Blue Mining programme will help policymakers decide whether these deposits could and should be exploited: “There are sensitivities around mining and always have been.”

Note: The article originally said the extinct vent systems are “devoid of life”.

They are devoid of typical vent species, but other species live there.