See a map of them all.

From Vox by Phil Edwards

Cables lying on the seafloor bring the internet to the world.

They transmit 99 percent of international data, make transoceanic communication possible in an instant, and serve as a loose proxy for the international trade that connects advanced economies.

Animated map reveals the 550,000 miles of cable hidden under the ocean that power the internet

Every time you visit a web page or send an email, data is being sent and received through an intricate cable system that stretches around the globe.

Since the 1850s, we've been laying cables across oceans to become better connected.

Today, there are hundreds of thousands of miles of fiber optic cables constantly transmitting data between nations.

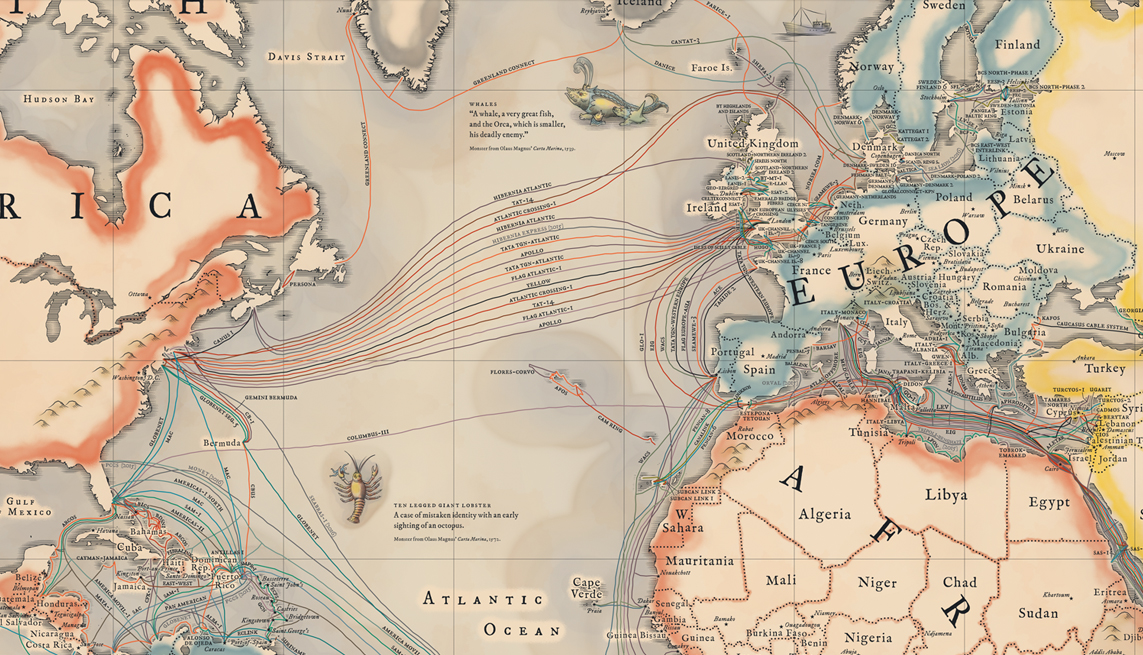

Their importance and proliferation inspired Telegeography to make this vintage-inspired map of the cables that connect the internet.

It depicts the 299 cables that are active, under construction, or will be funded by the end of this year.

In addition to seeing the cables, you'll find information about "latency" at the bottom of the map (how long it takes for information to transmit) and "lit capacity" in the corners (which shows how much traffic a system can send, usually measured in terabytes).

You can browse a full zoomable version here.

The cables are so widely used, as opposed to satellite transmission, because they're so reliable and fast: with high speeds and backup routes available, they rarely fail.

And that means they've become a key part of the global economy and the way the world connects.

Take, for example, the below map, which lets you slide between a 1912 map of trade routes and Telegeography's map of submarine cables today.

The economic interdependence has remained, but the methods and meaning have changed:

The submarine cable map shows economic connections in less-developed countries as well.

Cables between South America and Africa, for example, are much more scarce than trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific routes:

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3498666/africaandsouthamerica.0.jpg)

Connections in the South Atlantic are scarce. (Telegeography)

Though cables to developing countries are expanding, they have a lot of work to do before they catch up.

And Antarctica is left out completely (scientists down there get their internet from satellites).

The analogy between submarine cables and historic trade routes has a lot of caveats: trade routes were determined by geography as well as economic interests, and economic incentives were a lot different then than they are today.

It would also be a mistake to overlook physical goods in favor of the internet (just look at those giant container ships).

But both then and now, paths across the ocean require investment, trading partners on both sides, and a willingness to take risks.

Sailors took the gamble in the past, and tech companies are taking it now.

Submarine cables get big investments from companies looking to explore their own modern trade routes

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3498678/cablesinasia.0.jpg)

Submarine cables in Asia. (TeleGeography)

These cables carry information for the entire internet, including both corporate and consumer interests.

That's why Google invested $300 million in a trans-Pacific cable system consortium to move data, Facebook put money into an Asian cable system consortium, and the finance industry invests just as much to shave a few milliseconds off trade times.

Other consortia regularly lay cables to transmit the consumer internet.

Each group's control of a submarine cable is an advantage in the information exchange between countries.

Submarine cables are a 150-year-old idea with new potency

The SS Great Eastern laid the first continually successful trans-Atlantic cable in 1866, which was used to transmit telegraphs. Later cables (starting in 1956) carried telephone signals.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3498680/Atlantic_cable_Map.0.jpg)

A map of the submarine telegraph in 1858, though the attempt only worked for three weeks. (Wikimedia Commons)

Modern cables are surprisingly thin, considering how long they are and how deep they sink. Each is usually about 3 inches across.

They're actually thicker in more shallow areas, where they're often buried to protect against contact with fishing boats, marine beds, or other objects.

At the deepest point in the Japan Trench, cables are submerged under water 8,000 meters deep — which means submarine cables can go as deep as Mount Everest is high.

The optical fibers that actually carry the information are bundled within the larger shell of the cable:

A diagram of a submarine cable. (Wikimedia Commons)

The components include:

- Polyethylene

- Mylar tape

- Stranded metal (steel) wires

- Aluminum water barrier

- Polycarbonate

- Copper or aluminum tube

- Petroleum jelly (this helps protect the cables from the water)

- Optical fibers

These cables move the videos, trades, gifs, and articles that bring the internet around the world in a matter of milliseconds.

And that's the type of advantage any trader — digital or analog — could appreciate.

Links :

- Washington Post : As Russia scopes undersea cables, a shadow of the United States’ Cold War past

- NYTimes : Russian Ships Near Data Cables Are Too Close for U.S. Comfort

- NPR : What Would It Take To Cut U.S. Data Cables And Halt Internet Access?

- BBC : Could Russian submarines cut off the internet?

- Discover Mag : Sharks Are Chomping Underwater Fiber-Optic Cables

- GeoGarage blog : Messages from the deep: Interactive map plots the sprawling growth of the submarine cable network since 1989 / Submarine cables : how the net connected the world / Undersea cables are actually more vulnerable than you might think / Here’s how the Internet’s arteries travel across the world's oceans in 2014

The Diplomat : Undersea Cables: How Russia targets the West’s Soft Underbelly;

ReplyDeleteWashington is worried about Moscow’s ability to disrupt global Internet communications.

Wired : Undersea Internet cables are surprisingly vulnerable

ReplyDeleteCSMonitor : Why the Russian threat to undersea cables is overblown

ReplyDeleteTheAtlantic : What's Important About Underwater Internet Cables

ReplyDelete