Saturday, April 11, 2015

Friday, April 10, 2015

Wiring the world below

A network of permanent observatories will soon monitor the oceans

From The Economist

The planet arrogantly dubbed “Earth” by its dominant terrestrial species might more accurately be called “Sea”.

Seven-tenths of its surface is ocean, yet humanity’s need to breathe air and its inability to resist pressure means this part of the orb is barely understood.

In June a project designed to help correct that will open for business.

The seven sites of the United States’ Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI), scattered around the Atlantic, Pacific and Southern oceans, will measure physical, chemical, geological and biological phenomena from the seabed to the surface.

They will join three similar Canadian facilities, VENUS and NEPTUNE in the Pacific, which have been operating since 2006 and 2009 respectively, and the Arctic observatory in Cambridge Bay, an inlet of the Arctic Ocean, which opened in 2012.

The American project was conceived jointly with Canada, which secured funding first.

Canada’s near decade-long operational experience should help to provide pointers to make the bigger operation a success.

The OOI’s metaphorical flagship is the Cabled Array, which is being deployed off the coasts of Oregon and Washington, to the south of VENUS and NEPTUNE, with which it will collaborate.

In particular, these observatories have a remit to study a suboceanic piece of the Earth’s crust called the Juan de Fuca plate, which is being overridden by the North American plate’s progress westward as part of the stately geological dance called plate tectonics.

As its name suggests, the Cabled Array is organised around a submarine cable—a 900km-long power and data connection between its base in Oregon and its seven submarine nodes (see illustration). These nodes are linked, in turn, to 17 junction boxes that distribute power and signals to the system’s instruments, and collect data from them. It is also connected to “profiler moorings” that let instruments travel up and down a wire stretching from the surface to the bottom, allowing a cross-section of the water column to be sampled at regular intervals.

Strange life

One of the Cabled Array’s jobs is to measure the Juan de Fuca plate’s volcanic and seismological activity, including the output of its hydrothermal vents—submarine springs from which superheated mineral-laden water emerges.

These support very unusual forms of life which are not found in any other habitat.

It will also, though, study more quotidian matters, such as ocean currents and chemistry, and the biological productivity of the area.

The other six observatories are tied to moorings and are powered by battery, sun and wind.

They will send their data ashore via satellite.

Like the Cabled Array, each has at least one profiler mooring and also a range of instruments at various fixed depths.

These moored observatories, though, can reach out beyond the range of their fixed instruments using robots.

Slocum Teledyne glider

Most of these robots are torpedo-shaped ocean gliders (one of which is pictured above) that “fly” long distances through the sea, sampling sunlight penetration, chlorophyll and oxygen concentrations, and the density, pressure, temperature and salinity of the water.

The ocean gliders travel by slowly decreasing their buoyancy to sink, and then increasing it again to rise.

The hydrodynamic shape of their wings means that both rising and falling drives them forward at a leisurely rate of about 1.5kph.

One observatory, called Pioneer, is also equipped with propeller-driven autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), that can swim more strongly against currents.

It is one of two moored close to shore—in its case, the shore of New England.

The other, Endurance, is off the coast of Oregon.

Both will measure processes such as upwelling (important for the recycling of nutrients that have fallen to the seabed), oxygen depletion (which is often caused by pollution), and the dramatic changes in water temperature, salinity and currents that happen where the continental shelf dives into the abyss.

The remaining four observatories are stationed in deeper water.

At their sites the seabed is between 2,800 and 5,200 metres below the surface.

Irminger Sea is next to Greenland; Argentine Basin lies in the South Atlantic; Southern Ocean is stationed off Chile’s southern tip; Ocean Station Papa is in the Gulf of Alaska.

Each of these observatories will sit at one corner of a triangular study area with sides up to 62km long, the other corners of which are occupied by fixed daughter stations.

Each study area will also be patrolled by gliders.

In combination, the OOI’s seven observatories will carry 830 instruments, including 32 gliders and three AUVs.

The wealth of data this equipment produces will be funnelled back to Rutgers University in New Jersey and then, as is increasingly required of science, made immediately available to all and sundry. This is, after all, a taxpayer-financed project—to the tune of $385m for the construction alone.

Not everyone is happy with such open access.

Some old-school oceanographers worry that they will work on a question thrown up by the data, only to be scooped.

Many, no doubt, are more used to going to sea to collect samples than having data delivered to their desks.

A report earlier this year by America’s National Academy of Sciences was less than enthusiastic about the OOI.

It found “a lack of broad community support for this initiative, exacerbated by an apparent absence of scientific oversight during the construction process”.

That absence, though, was probably one reason the project’s co-ordinators, a not-for-profit group called the Consortium for Ocean Leadership, managed to adhere to the OOI’s construction timetable.

Having a plan and sticking to it without other people shoving their oars in always makes it easier for contractors to meet their deadlines.

Whether such punctuality has been bought at the expense of scientific effectiveness remains to be seen.

And failures there will no doubt be.

VENUS and NEPTUNE have suffered from corroded instruments, underwater landslides and damage from trawler nets.

Canada has learned from these problems.

For instance, it now discuss the project with fishermen and points out where equipment is located. Some researchers also think the OOI is short on staff.

Canada’s observatories have five researchers overseeing 180 instruments.

The OOI’s 830 will be overseen by a mere quartet.

Axial Seamount : Understanding submarine volcanoes

Undersea observatories are ambitious projects, so it will take time to get them right and attract people to use the free data.

One way the organisers hope to entice users is by putting instruments on Axial Seamount, an underwater volcano about 480km west of Oregon that could erupt at any time.

Being able to monitor an undersea eruption live would be exciting—and not something conventional research methods could manage.

There is nothing like a firework display to attract a crowd.

Links :

Thursday, April 9, 2015

Piling sand in a disputed Sea, China literally gains ground

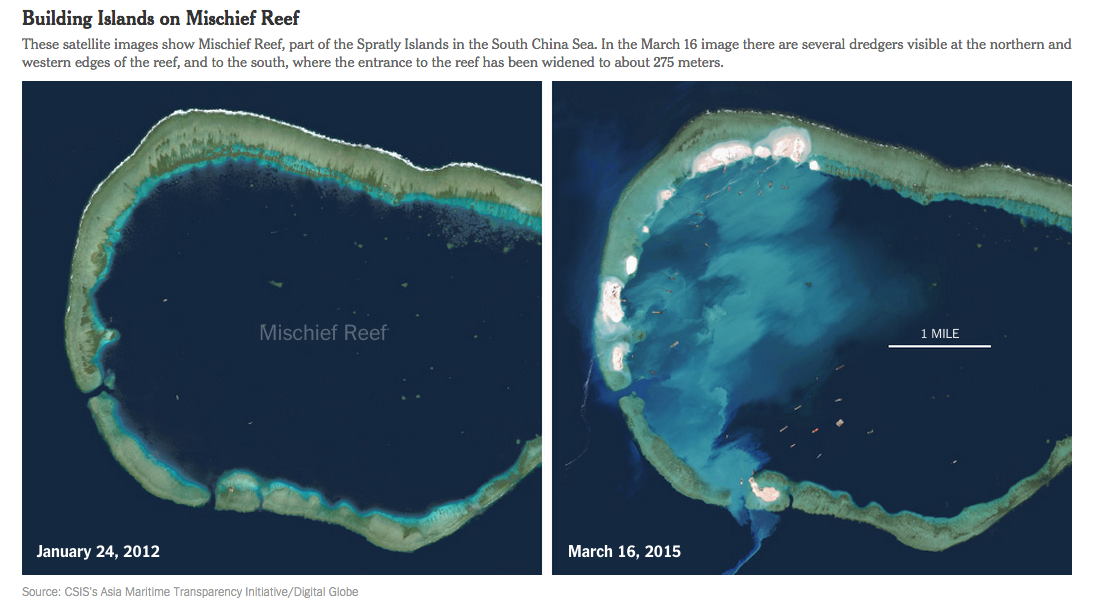

A satellite image from March 16 shows work on an emerging artificial island at Mischief Reef in the South China Sea.

Center for Strategic and International Studies, via Digital Globe

From NYTimes by David E. Sanger & Rick Gladstone

The clusters of Chinese vessels busily dredge white sand and pump it onto partly submerged coral, aptly named Mischief Reef, transforming it into an island.

Over

a matter of weeks, satellite photographs show the island growing

bigger, its few shacks on stilts replaced by buildings.

What appears to

be an amphibious warship, capable of holding 500 to 800 troops, patrols

the reef’s southern opening.

China

has long asserted ownership of the archipelago in the South China Sea

known as the Spratly Islands, also claimed by at least three other

countries, including the Philippines, an American ally. But the series

of detailed photographs taken of Mischief Reef shows the remarkable

speed, scale and ambition of China’s effort to literally gain ground in the dispute.

The

photographs show that since January, China has been dredging enormous

amounts of sand from around the reef and using it to build up land mass —

what military analysts at the Pentagon are calling “facts on the water”

— hundreds of miles from the Chinese mainland.

see Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (CSIS)

The Chinese have clearly concluded that it is unlikely anyone will challenge them in an area believed rich in oil

and gas and, perhaps more important, strategically vital.

Last week

Adm. Harry Harris, the commander of the United States Pacific fleet,

accused China of undertaking an enormous and unprecedented artificial

land creation operation.

“China is creating a great wall of sand with dredges and bulldozers,” Admiral Harris said in a speech in Canberra, Australia.

ENC China charts

Defense

Secretary Ashton B. Carter, on his first trip to Asia, put the American

concerns in more diplomatic language, but the message was the same.

In

an interview to coincide with his visit, published Wednesday in the

Yomiuri Shimbun, one of Japan’s largest dailies, Mr. Carter said China’s

actions “seriously increase tensions and reduce prospects for

diplomatic solutions” in territory claimed by the Philippines and

Vietnam, and indirectly by Taiwan.

He

urged Beijing to “limit its activities and exercise restraint to

improve regional trust.”

That is the same diplomatic message the Obama

administration has been giving to China since Hillary Rodham Clinton,

then the secretary of state, and her Chinese counterpart faced off over

the issue at an Asian summit meeting in 2010.

While

other countries in Southeast Asia, like Malaysia and Vietnam, have used

similar techniques to extend or enlarge territory, none have China’s

dredging and construction power.

The new satellite photographs were taken by DigitalGlobe, a commercial satellite imagery provider, and analyzed by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington research group. They certainly confirm the worries expressed by both Mr. Carter and Admiral Harris.

“China’s

building activities at Mischief Reef are the latest evidence that

Beijing’s land reclamation is widespread and systematic,” said Mira

Rapp-Hooper, director of the center’s Asia Maritime Transparency

Initiative, a website devoted to monitoring activity on the disputed

territory.

A Chinese facility on Hughes Reef in the South China Sea.

(William Colson/CSIS)

The

transformation of Mischief Reef, which the Chinese call Meiji Reef, she

said, is within territory claimed by the Philippines and is one of

seven small outposts the Chinese have sought to establish in the South

China Sea.

“These will allow Beijing to conduct regular, sustained

patrols of the airspace and water, and to attempt to press its far-flung

maritime claims as many as 1,000 miles from its shores,” she said.

Although

these outposts are too vulnerable for China to use in wartime, she

said, “they could certainly allow it to exert significant pressure on

other South China Sea claimants, such as the Philippines and Vietnam.”

The

issue poses a problem for the Obama administration, not simply because

the Philippines is a treaty ally.

China is working so quickly that its

assertion of sovereignty could become a fait accompli before anything

can be done to stop it.

Mischief (march 16, 2015)

The southern platform has been further expanded using sand recovered from the reef's southern entrance.

The entrance itself has been expanded to a width of approximately 275 m.

The

United States has long insisted that the territorial disputes be

resolved peacefully, and that no claimant should interfere with

international navigation or take steps that impede a diplomatic

resolution of the issue.

But to the Chinese — already flexing muscle in

other territorial disputes and with the creation of an Asian infrastructure bank to challenge the Western-created World Bank — this is not a matter for negotiation.

When

Mrs. Clinton raised the issue in Hanoi five years ago at the Asian

Regional Forum, her Chinese counterpart, Yang Jiechi, responded with a

25-minute speech, exclaiming: “China is a big country. Bigger than any

other countries here.”

It seemed to be a reminder that its military

could make sure no one would dare challenge its building spree on

disputed territory — and so far, no one has, other than with diplomatic

protests.

Since

then, China has made no secret of its territorial designs on the

Spratlys, creating at least three new islands that could serve as bases

for Chinese surveillance and as resupply stations for navy vessels,

according to IHS Jane’s.

Satellite imagery of the Spratlys publicized by IHS Jane’s in November showed

how the Chinese had created an island about 9,850 feet long and 985

feet wide on Fiery Cross Reef, about 200 miles west of Mischief Reef,

with a harbor capable of docking warships.

IHS Jane’s said the new

island could support a runway for military aircraft.

The

United States is about to conduct a joint military exercise with the

Philippines, part of an emerging Obama administration strategy to keep

American ships traversing the area regularly, a way of pushing back on

Chinese claims of exclusive rights.

The administration did the same when

China declared an air defense zone in the region more than a year ago.

The

Chinese have said they consider most of the South China Sea to be

rightfully theirs — a claim others make as well.

China and Japan have a

separate territorial dispute over islands that Japan calls the Senkaku

and China calls the Diaoyutai.

Those tensions have eased slightly in

recent times.

Last year, China and Vietnam became entangled in an angry exchange after China towed a $1 billion oil drilling rig to an area 150 miles off Vietnam’s coast.

On Tuesday China’s official Xinhua news agency reported

that the leaders of both countries wanted to soothe their differences

and “control their disputes to ensure that the bilateral relationship

will develop in a right track.”

- New York Times : A Game of Shark and Minnow - Dangerous Ground in the South China Sea

- Quartz : China’s island-building spree is about more than just military might

- The Economist : Such quantities of sand

- WSJ : Meet the Chinese Maritime Militia Waging a ‘People’s War at Sea’

- Medium : Satellite image analysis

- GeoGarage blog : Manila says China starts dredging at another reef in disputed waters / China’s lawful position on the South China Sea

Wednesday, April 8, 2015

Brazil DHN update in the Marine GeoGarage

As our public viewer is not yet available

(currently under construction, upgrading to a new webmapping technology

as Google Maps v2 is officially no more supported),

this info is primarily intended to our universal mobile application users

(Marine Brazil iPhone-iPad on the Apple Store / Weather 4D Android -App-in- on the PlayStore)

and also to our B2B customers which use our nautical charts layers

in their own webmapping applications through our GeoGarage API.

DHN coverage

(currently under construction, upgrading to a new webmapping technology

as Google Maps v2 is officially no more supported),

this info is primarily intended to our universal mobile application users

(Marine Brazil iPhone-iPad on the Apple Store / Weather 4D Android -App-in- on the PlayStore)

and also to our B2B customers which use our nautical charts layers

in their own webmapping applications through our GeoGarage API.

1 chart added & 15 charts has been updated since the last update

DHN update March 2015 (15/03 & 30/03)

- 1703 PORTO DE CANANÉIA

- 204 DAS ILHAS PEDREIRA À ILHA DE SANTANA

- 242 DA ILHA DOS PORCOS À BAÍA DO VIEIRA GRANDE

- 302 DE SALINÓPOLIS AO CANAL DO ESPADARTE

- 511 BARRA DOS RIOS TIMONHA E UBATUBA

- 1410 PROXIMIDADES DOS PORTOS DE VITORIA E TUBARÃO

- 1513 TERMINAIS DA BAÍA DE GUANABARA

- 1515 BAÍA DE GUANABARA - ILHA DO MOCANGUÊ E PROXIMIDADES

- 1531 ILHA DO BOQUEIRÃO E ADJACÊNCIA

- 1550 BACIA DE CAMPOS

- 1623 PORTO DE ITAGUAÍ

- 1701 PORTO DE SANTOS

- 21050 (INT.2006) DO RIO ITARIRI AO ARQUIPÉLAGO DOS ABROLHOS

- 23300 (INT.2126) DE PARANAGUÁ A IMBITUBA

- 2792 LAGO DE BRASÍLIA

- 4106A DE ITACOATIARA À ILHA DA GRANDE EVA NEW

Today 472 charts (513 including sub-charts) from DHN are displayed in the Marine GeoGarage

Don't forget to visit the NtM Notices to Mariners (Avisos aos Navegantes)

The $37 Billion oil spill

Recovery is in full swing, and much of the coast in already bouncing back.

Photo: iStock

From Outside by Kim Cross

Five years after the Deepwater Horizon disaster, we wanted to know whether the Gulf had recovered—and how much remains to be done.

Everyone remembers how it started: on April 20, 2010, the Deepwater Horizon drilling platform exploded off the coast of Louisiana, rupturing the Macondo well below it.

Over the next 87 days, as much as four million barrels of oil surged into the Gulf of Mexico—the worst marine spill in history.

Over the ensuing weeks, BP, which operated the rig, launched a massive cleanup campaign: 810,000 barrels of oil were skimmed off the surface or captured from the wellhead, 1.8 million gallons of chemical dispersant were pumped into the waters, 411 surface fires were lit, miles of floating booms were deployed, and tens of thousands of workers cleaned beaches.

Whether you turned on Fox News or the Today show, the Gulf was the story.

This year, what few headlines have appeared have focused on the third and final phase of a federal trial in Louisiana to determine how much BP can be fined under the Clean Water Act.

(A judge ruled that it should fall between $3 billion and $14 billion.)

Combined with previous fines and forthcoming penalties for damage to wildlife, the company will have spent nearly $40 billion in restitution.

“No company has done more to respond to an industrial accident,” says BP spokesman Jason Ryan.

These days you’re more likely to see an ad for Louisiana tourism (paid for, in part, by BP) than any coverage of the lingering recovery effort.

I lived on this coast for years, first on the Florida Panhandle and then in New Orleans.

I’ve swum in its waters and eaten its seafood more times than I can remember.

So last December, I decided to return to the area and check on the progress myself.

What Happened to the Oil?

There’s one thing that almost everyone agrees on: it’s not as bad as it could have been.

In large part, this is due to bacteria that appear to have evolved to feed on the million or so barrels’ worth of oil that naturally seeps from the Gulf floor each year.

When the spill happened, that bacteria quickly consumed many of the alkanes found in the crude.

By 2011, six months after the well was capped, the plume had disappeared.

But other hydrocarbons were left behind.

According to Chris Reddy, a senior scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute*, “Oil is a complex mixture; it’s like a buffet. The prime rib is gone, and now the crusted-over coleslaw”—the part the bacteria didn’t consume—“is still there.”

Photo: Deepwater Horizon Response/Flickr

In 2010, BP committed $500 million in funding for the Gulf of Mexico Research Institute to examine the leak’s long-term impact.

BP also went on a hiring spree.

The company paid hundreds of scientists to study the spill in preparation for litigation, but they were bound by a gag order.

The first time many of them spoke was when they testified—on BP’s behalf—at the trial in Louisiana.

Today, no one’s really sure how much oil is still out there.

In 2010, the White House released a report claiming that only 26 percent of the spill remained in the Gulf. Scientists torpedoed the findings for not being peer reviewed.

Furthermore, the only known quantity, according to Samantha Joye, a marine scientist at the University of Georgia, was how much oil was skimmed off the surface or captured at the wellhead—every other number is at best an estimate.

This much is certain: there’s still a big mess on the seafloor. Joye saw it first in 2010, when she began studying the effects of the spill, and again in April 2014.

On both occasions, she descended 5,000 feet in a submarine and found a layer of mud mixed with oil near the blowout site.

“The mysterious caramel brown layer that we discovered in 2010 remains,” she noted in 2014.

“It is about the same thickness as it was in 2010 [between five and seven centimeters], and it is widespread—we drove around for over 2.5 km [1.5 miles] and saw the feature everywhere.”

That lines up with Reddy’s October 2014 report that there was a “bathtub ring” of crude the size of Rhode Island on the seafloor.

Perhaps more disconcerting is what we’ve since learned about Corexit,

the dispersant pumped into the water.

Corexit was supposed to break down the oil but also made it more edible to fish and plankton, which otherwise don’t consume it.

Even worse, there’s some evidence that the chemical actually hindered degradation, allowing more hydrocarbons to remain in the Gulf.

What Happened to the Fish?Corexit was supposed to break down the oil but also made it more edible to fish and plankton, which otherwise don’t consume it.

Even worse, there’s some evidence that the chemical actually hindered degradation, allowing more hydrocarbons to remain in the Gulf.

How the oil will affect marine life over time remains to be seen.

In the year following the spill, nearly 7,000 animals were found dead: more than 6,000 birds, 600 sea turtles, and 150 marine mammals, including dolphins and sperm whales.

Photo: Deepwater Horizon Response/Flickr

Since then, however, there have been signs that populations are bouncing back.

During her 2014 dive, Joye observed a multitude of fish, squid, and eels—a marked contrast to 2010, when she saw one crab in seven hours.

A recent study found that brown and white shrimp were more abundant in estuaries heavily affected by the spill.

Shortly after the explosion, 37 percent of the Gulf was closed to fishing, for safety reasons and to allow populations to rebound.

By April 2011, most closures were lifted, though a few areas remained off-limits until 2014.

Today, commercial catches of shrimp, crabs, and yellowfin tuna remain lower than before the explosion in eight of the region’s most significant fisheries (though revenues as a whole have grown by 50 percent).

As populations struggle to recover, the scientific focus has shifted to how toxins work their way up the food chain.

Of particular concern are polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs, the carcinogens associated with charred meat), which comprise between 2 and 10 percent of crude oil.

The livers of vertebrates—fish, birds, humans—filter PAHs readily, but they can build up in the invertebrates, like lobsters and clams, fed on by larger fish.

And because the spill struck during breeding season, the embryos and larvae of many species may have been harmed.

There have been signs that marine-life populations are bouncing back. During a 2014 dive, biologist Samantha Joyce observed a multitude of fish, squid, and eels—a marked contrast to 2010, when she saw one crab in seven hours.">

“Those creatures influence the species they feed on and also the species that feed on them,” says Peter Hodson, an emeritus environmental-studies professor at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario.

“If you knock out those embryos, the effects on fish populations could take years to see.” One species already struggling is oysters, populations of which have plummeted in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama.

“My production is down 93 percent,” says George Barisich, an oyster farmer and shrimper from Louisiana’s St. Bernard Parish.

“They’re not contaminated to where it’ll make you sick, but there are no babies.”

What Happened to the People?

If you visit the Gulf shore today, you’ll see the same Caribbean-blue water and sugar-white sand that have enchanted generations.

“The Gulf is undergoing a robust recovery,” says BP’s Ryan.

“It’s still beautiful,” says Phillip McDonald, executive chef at Bud and Alley’s Pizza Bar in Seaside, Florida. “I just went surfing yesterday. There are nickel-size tar balls here and there, but those were there before the oil spill, occasionally.”

There are, after all, roughly 2,400 oil platforms in the Gulf.

While observers predicted tough times for energy companies after the explosion, those never came to pass.

Production is down 27 percent across the Gulf, but that looks to change as more leases become available on prime real estate.

In 2012, President Obama opened 39 million new acres to drilling; in 2014, he approved offshore fracking.

Big Oil still has it good.

So do the beach towns.

“Since 2011, this area has had some of its best years for tourism,” says Michael Sturdivant, chairman of the Emerald Coast chapter of the Surfrider Foundation, an environmental watchdog group.

But Sturdivant and others are concerned about how much oil remains in the ocean, estuaries, and marshes—and how that might affect residents.

There are “tens of thousands of people in the coastal area” suffering from symptoms associated with oil exposure, according to Wilma Subra, a former EPA adviser who now assists the Louisiana Environmental Action Network.

“We’re seeing a lot of respiratory problems but also cardiovascular issues, memory loss, and degradation of organs.”

Photo: Deepwater Horizon Response/Flickr

Proving that those symptoms are oil-related requires longitudinal studies that can take years.

Two big ones are under way: The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences is conducting a ten-year study on the health effects of a spill, monitoring 33,000 cleanup workers and coastal residents. (It’s the largest such study in history.)

And a five-year project by a consortium of five universities is measuring PAH levels in subsistence-fishing communities.

Then there are the 115 men and women who survived the explosion itself, many of whom, like Stephen Stone, suffer from post-traumatic stress.

“It’s not over,” his wife, Sara, told me in December.

“These are not incidents that happen and have an ending.”

That’s precisely the trouble with the situation in the Gulf.

BP will someday move on, but scientists are likely to remain busy for decades to come.

How the Gulf will look in 20 years is anyone’s guess.

Over the past few years, I’ve caught glimpses of the achingly beautiful Gulf of my childhood, and I’ve found myself in awe of its resilience.

But I can’t shake the fear that some unseen danger is still out there threatening to upset the balance.

“You can’t put the Gulf in an MRI and find specific problems in an ecosystem this diverse and complex,” says Chris Reddy.

“We’re going to have to live with large uncertainties for a very long time.”

What the Oil Spill Cost BP (So Far)

Initial Response and Cleanup: $14.3 billion

Litigation, Medical and Financial Claims, and Marketing:

Financial and property damage: $11.6 billionGovernment advances, claims, and settlements: $769.3 million

Coast Guard cleanup reimbursement: $704.7 million

Tourism promotion: $179 million

Health outreach: $79.7 million

Seafood marketing settlement: $57 million

Realtor compensation program: $54 million

Behavioral health program: $52 million

Seafood marketing: $48.5 million

Goodwill marketing: $27.1 million

Seafood testing: $25.4 million

Medical claims: $331,600

Criminal Fines:

Science and wildlife foundations: $765 million

Spill liability and wetlands restoration: $750 million

SEC securities fraud penalty: $525 million

Manslaughter and obstruction of Congress fines: $6 million

Environmental Costs:

Natural resources damage assessment funding: $1.2 billion

Early habitat restoration: $629 million

Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (funding to date): $315 million

Clean Water Act Penalty: $3.5 billion (so far. In January, a Louisiana judge ruled BP grossly negligent, which could push its CWA fines as high as $14 billion.)

Administrative Costs: $1.5 billion

Total: $37.1 billion Links :

- Scientific American : The BP Oil Spill 5 Years After: How Has It Affected You?

- Washington Post : Study suggests chemical used in BP oil spill cleanup capable of injuring people and wildlife

- GeoGarage blog : Where did all the oil from the Deepwater Horizon spill go? / Lasting scars three years on from BP oil disaster / BP oil spill: the environmental impact one year on / Deep sea BP spill dispersants didn't degrade for months /

Tuesday, April 7, 2015

NZ Linz update in the Marine GeoGarage

As our public viewer is not yet available

(currently under construction, upgrading to a new webmapping technology as Google Maps v2 is officially no more supported),

this info is primarily intended to our universal mobile application users

(Marine NZ iPhone-iPad on the Apple Store/ Weather 4D Android -App-in- on the PlayStore)

and our B2B customers which use our nautical charts layers

in their own webmapping applications through our GeoGarage API.

2 charts has been updated in the Marine GeoGarage

Today NZ Linz charts (183 charts / 323 including sub-charts) are displayed in the Marine GeoGarage.

Note : LINZ produces official nautical charts to aid safe navigation in New Zealand waters and certain areas of Antarctica and the South-West Pacific.

Note : LINZ produces official nautical charts to aid safe navigation in New Zealand waters and certain areas of Antarctica and the South-West Pacific.

Using charts safely involves keeping them up-to-date using Notices to Mariners

Reporting a Hazard to Navigation - H Note :

Mariners are requested to advise the New Zealand Hydrographic Authority at LINZ of the discovery of new or suspected dangers to navigation, or shortcomings in charts or publications.

Reporting a Hazard to Navigation - H Note :

Mariners are requested to advise the New Zealand Hydrographic Authority at LINZ of the discovery of new or suspected dangers to navigation, or shortcomings in charts or publications.

The Navy is designing a drone that flies and swims

| The Flimmer splashes down. (Credit: United States Naval Research Laboratory) |

From DiscoverMag by Carl Engelking

So why not find a drone that can do both?

That’s exactly what the Naval Research Laboratory’s Flimmer Program aims to do.

Early prototypes of the Flimmer — a portmanteau of “flying swimmer” — have successfully been launched from a plane at 1,000 feet, splashed down on the water’s surface, then dove underwater reaching speeds of 11 miles per hour.

Though the drone’s design still needs a lot of tweaking, it could someday be used to hunt enemy submarines from the air and sea.

The latest prototype of the Navy’s duck-like drone.

(Credit: United States Naval Research Laboratory)

The biggest hurdle for Flimmer’s designers is that water is roughly 1,000 times denser than air. Weight is the enemy of a flying drone, as heavier aircraft require more lift to stay airborne. Underwater craft, on the other hand, are built to be thick and heavy to protect electrical components from crushing under pressure.

The Flimmer needs to be light enough to fly, yet strong enough to handle the impact of a splashdown and water pressure.

Flimmer flight and splashdown

The latest version of the Flimmer is called the Flying WANDA, for “Wrasse-inspired Agile Near-shore Deformable-fin Automaton.”

It has fins tucked away at the end of its wings that fold upward to stabilize the craft in the air, while a rear propeller provides the thrust.

In the water, the rear fins, and a pair of fins near the front of the body, are used to steer.

In the air, WANDA can reach speeds up to 57 miles per hour, and clock 11 miles per hour underwater.

Concept Flimmer vehicle

The Navy envisions using their duck-like drone to provide quick reconnaissance by flying to a location, landing in the water and following an enemy submarine.

Engineers will continue to alter the Flimmer’s design to improve its air-to-sea abilities.

However, there’s no timeline for when the Flimmer will be deployed in enemy waters.

Links :

- US Navy NRL : Spectra Winter / Flying-Swimmer (Flimmer) UAV/UUV

- DefenseOne : This duck rrone could spy on enemy subs

Monday, April 6, 2015

Light the ocean

Light The Ocean is an entirely new perspective on the ocean world.

By combining data from scientists around the globe with specially developed computer animation software we are able to turn the waters of the ocean crystal clear.

We reveal spectacular underwater landscapes and hidden structures in the ocean itself.

We show how landscapes and water interact on unimaginable scales to create an ocean world as diverse in habitats as anywhere on dry land.

Our camera crews have also traveled the planet, from the Antarctic to the deep waters of the mid-Atlantic to capture spectacular new footage of the creatures that depend on these ocean habitats.

We follow sperm whales as they dive into the dark depths of the Kaikoura Canyon off New Zealand and we descend to the underwater mountain ranges of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge to find creatures never before seen

Sunday, April 5, 2015

Mountains of the sea: photographer ‘freezes’ waves to make them look like mountains

Sea Stills from Ray Collins

- other video -

From BoredPanda

Artists have wrestled with the raw,

majestic, natural power of the sea for hundreds of years, but

Australia-based photographer Ray Collins is one of the few who really

gets it right.

Collins’ epic wave photos seem to freeze and capture all

of the sea’s power, casting it in the respectful and majestic light that

it deserves.

Collins writes that “feels more at

home floating in saltwater with his camera than anywhere on land,” and

this comes across in his work.

He is an accomplished surf sport

photographer as well, but his most powerful photos are of the sea itself

as a subject or even as a character.

“It’s very hard to describe what I see to someone without a visual representation of it”

“I actually work in a coal mine, believe it or not. I work there 3 days a week and I shoot for 4″

“Some of my images take months of planning. Airfares, accommodation, swell forecasting, reading weather maps, talking to locals, getting the right gear for the climate and then patiently waiting for it to unfold”

“On the other hand, I can walk out of my front door, cross the road onto the beach, swim out and shoot a beautiful image of a wave as the sun rises over the sea. Every image has a different story”

“I just want to keep improving and keep challenging myself - physically as a human being swimming in the ocean and constantly evolving and pushing my own limits as an image maker”

“At the moment I’m mainly shooting with a D4 and D810, and the lenses are usually fixed mid length primes from 14mm all the way to 400mm. I also use Aquatech waterhousings to keep my cameras and lenses dry”

Be sure to check out more of his photos on his site