Created in the 1530s, the "Carta Marina" was full of mythical beasts and terrors; so was my Northern Ireland neighborhood.

Madison McVeigh/CityLab

From The City Lab by Darran Anderson

Growing up amid the political conflict in Northern Ireland, a 16th-century map that blended real and mythical monsters spoke to my fears and fascinations.

My grandfather was a cartographer, though not in an academic sense.

For decades, he earned a living on the sea, primarily as a fisherman but also as a smuggler, a minesweeper, and a retriever of the drowned.

Visiting his house as a boy, I was captivated by the nautical objects he had assembled: tide charts, barometers, knots and hooks, flotsam and jetsam.

Amongst these items were maps of rivers, loughs, the islands that peppered the north and west Irish coast (now called the Wild Atlantic Way); all of them were filled with mysterious symbols.

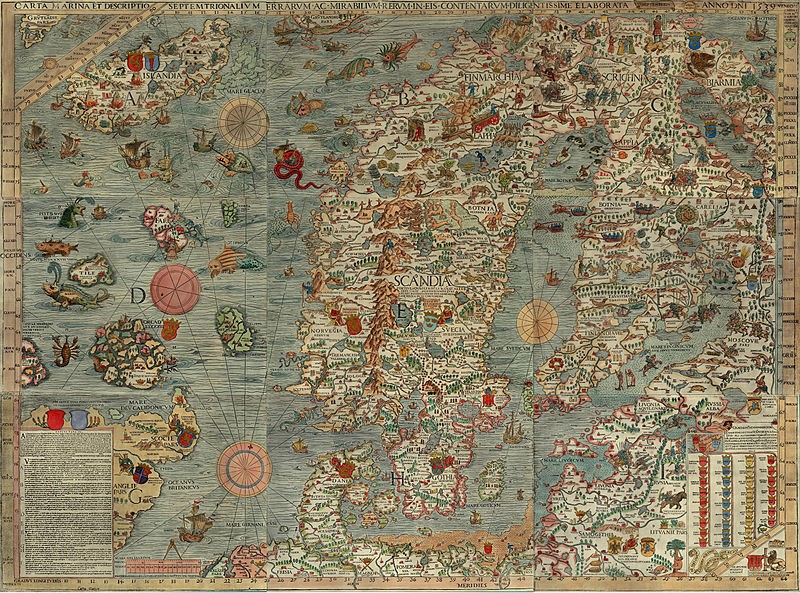

The Carta Marina in all its otherworldly majesty.

(Word Digital Library)

But there was one map my grandfather kept that intrigued me above all others: the Carta Marina. Crafted by a Swedish exile, the Carta Marina was initiated in the Baltic port of Danzig in 1527, and published in Venice twelve years later.

Its creator was Olaus Magnus, a clergyman who created his map to try and convince the Catholic Church to retake the north after Sweden had turned to Lutheranism.

Though imitated by other maps, the Carta Marina was lost for centuries.

In 1886, an original turned up in the Bavarian State Library in Munich, with another reappearing in the early 1960s in Switzerland, eventually making its way to Sweden (unlike its creator).

In the early 1980s, it took up residence in my imagination, via my grandfather’s collection.

It beguiled child observers like myself, who’d recently outgrown Where the Wild Things Are and wished to find real-life wonders and terrors.

And I did find them: I grew up in Derry, near the border between the U.K.

and the Republic of Ireland and then immersed in the violence and division of the Troubles.

Perched at the edge of Europe, it was a place, like Magnus’ north, that was far from the centers of power in London, Dublin, and Brussels.

Though remarkably accurate geographically for its time, the Carta Marina was far more than just a representation of space.

To demystify the opaque frozen north and show it was rich and multitudinous, Magnus populated his map with livelihoods and activities, rituals and superstitions, a menagerie of real animals and surreal monsters.

It was a chart not simply of land and sea but a chart of psychology (including Magnus’ own biases), sociology, religion, weather, folklore, flora and fauna, fears and dreams, the clashing of human beings with terrible creatures and with each other.

Other maps of that era might warn “Here be dragons,” but the Carta Marina revealed them.

There was the fabled Leviathan rising and spouting two great arcs of brine with a vessel in its sights.

Sailors desperately tried to scare off abyssal monsters using bugles.

Serpents from the deep coiled around ships.

Magnus annotated each one, to give credence to their reported sightings and legend.

The grotesque sea-pig he pictured with eyes on its back, for example, had been spotted in the North Sea while he was assembling his map.

As vivid as these creatures are, they only hint at the vast alien world that existed beneath the waves; the sea-owl “Xiphias” is, for example, being attacked by another creature, implying a whole monstrous food chain and concealed ecosystem.

Even at its most extravagant, the Carta Marina has its own logic.

Its fictions contain fragments of truth, or at least attempts to reach it.

The supernatural conjecture was a symbolic reflection of the brutally real perils faced by sailors and travelers of Magnus’ era.

It was an attempt to find out why men sailed off and never returned to their families, and a tacit acknowledgement of ignorance.

There was practical wisdom within the map.

In certain areas, Magnus suggests at shipwrecks as well as accumulations of driftwood, pointing out places prone to perilous currents and changeable weather conditions—whether the treacherous Circius wind (“all who are sailing there must fear its horrifying and lethal effects”) or the perilous maelstrom (“Moskenstraumen”) near the Lofoten Islands.

Life’s rich tapestry can be found in the Carta Marina.

It is zoological, with polar bears on ice floes, wolfpacks and elks battling on ice, shepherds fending off snakes, beavers building dams, and bears climbing trees to steal honey.

(There is also an auroch goring the horse of a knight, a now-extinct animal that has since lost its one-sided struggle with mankind.) It is geological, with the burning mountains of Iceland demonstrating the geothermal activity of the island.

It is scientific, with Magnus revealing that he was aware that magnetic north and the geographic North Pole were in different places.

It is even philosophical, with Magnus suggesting that the giant Starkather—a legendary hero in Norse mythology, pictured on the map holding two huge rune stones—was great not just physically but in moral stature.

Borrowing stories from folklore, first-hand observations from his younger days of travels, and imagery from earlier artists, Magnus showed how different cultures responded with ingenuity to a harsh environment.

It is not a world without its dangers, even beyond the elements: Magnus charts deadly springs, a rock from which two murderous pirates operate, a body of water where a man is picked apart by sharks.

Even in the political aspects of the map, where he shows the kings and tsars of the various countries, it is an uneasy and potentially changeable situation (a wink to his papal audience), with the enthroned kings of Norway and Sweden staring across at each other.

Soon, the Carta Marina began to influence how I saw my own surroundings, and I began to draw my own maps.

I focused on charting my neighborhood: a run-down working-class Catholic and Irish Republican area, made up of terraced houses that had once housed Victorian shipbuilders.

I drew wind-roses, compass points, cherubs blowing winds.

I recorded the hiding places only my fellow street urchins and I knew of, beyond the sight of adults.

I mapped places where suspected treasure lay, like a small orchard in an alleyway, and places where perils beckoned, like a Brutalist block of flats, the glass-strewn alleyways, and the British Army watchtower that loomed over us in Rosemount.

I even created “Here be dragons”-esque creatures in the forbidden Glen, a wild wasteland area that we were continually warned away from and thus seemed to us to be full of adventures.

Everywhere peripheral is a center for someone.

The maps were my attempts to gradually expand my edges of ignorance, in a place and time filled with poverty, conflict and trauma.

Though I no longer have any of them in my possession, the maps I drew became a vital tool in helping me find my place in the urban fabric and, where necessary, invent it.

In the Carta Marina, too, myths also served functions, not least recording how the inhabitants of these lands saw the world, rationalized it to themselves and found their place in it.

Reading between the lines, their fears and desires are evident.

There are holy mountains and cursed places where the damned souls of men wail beneath the ice.

Places where demons attack cattle; places so abundant that cows will burst if allowed to graze unattended.

Is there any story that encapsulates the uncanny shock and grief of the loved ones of drowned sailors that Magnus’s recounting of the dead appearing at the doors of their homes on the day they died, unable to enter?

For the past decade, I have been exploring, writing and talking about different cities.

But only recently have I begun to realize that all of this is, in a sense, a continuation of those childhood maps and their naïve attempts to understand the places we inhabit.

Unwittingly, I had still been borrowing from Magnus.

After he completed the Carta Marina, the Swedish clergyman began writing an accompanying volume entitled Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus (“a description of northern peoples”), which sprawled into a colossal work.

Self-published in Rome in 1555, it’s a similarly multi-disciplined work, filled with accounts of elaborate snowball battles, descriptions of different kinds of frosts and winds, horse-racing across frozen lakes, statues that guard the mountains, military campaigns, ghosts and elves, witches and wizards, gravestones and magnets, comets and moonlight.

My forthcoming book Inventory (Chatto & Windus/ Farrar, Straus and Giroux) is partly about the damaging legacy of the Troubles and the suicide epidemic among young men in Derry.

As I wrote the opening chapter, I remembered my childhood maps.

There was a shared sense with Magnus of trying to shed light on a marginal place and people, somewhere that had been ignored, feared and silenced for so long, as fearful “barbarians” in the north.

The dangers in writing about it were to do so with excessive romanticism or righteousness.

My grandfather always cautioned against treating the sea with anything but realism.

He had experienced terrible storms where they prayed for their lives.

He had brought mines to the surface at great peril.

He had dredged up the bloated bodies of suicide victims to bring back to their families.

When I listened to The Shipping Forecast on the BBC radio night, I heard poetry.

My grandfather heard matters of life-and-death importance.

I thought again of the Carta Marina with the recent killing in Derry of Lyra McKee, a fellow journalist also working on the Troubles’ legacy of deprivation and suicide.

While observing dissident republican riots in Creggan, McKee was shot by a member of the New IRA.

The initial temptation was to think, in regards to the republican dissidents who took her life, that the terrible creatures on the map were closer to the truth than I’d realized as a child.

There were dragons after all.

Yet this would be a betrayal of Lyra McKee’s outlook and approach.

There are no monsters, only individuals, however lost, brutal, and culpable they are.

It is surely no coincidence that violence has erupted in one of the most deprived areas of one of the most deprived cities in the U.K., a city left behind and facing a grim future.

It is surely no coincidence that paramilitary groups are recruiting young men in a city where they face high rates of joblessness, neglected education, and lack of opportunities.

It is surely no coincidence that the uncertainty of the Brexit negotiations and the vacuum left by a hamstrung power-sharing assembly has seen the rise of gangsters and ideologues, rebranded for a generation with no memory of the Troubles.

If I was a child mapping my hometown now, it would, once again, have all manner of symbolic perils.

Hope is scarce, yet fear and despondency profit no one but the cynics.

Before her life was brutally cut short, Lyra McKee showed us how necessary it is to cast light on what is really happening, in a spirit of bravery and openness, and to chart the places and people who have been left off the maps, lest we all live in ignorance of our own frozen norths.

Links :

- Slate : Here Be Duck Trees and Sea Swine

- ScienceAlert : Why Do People See Serpent-Like Sea Monsters? It Could Come Back to Science

- Smithsonian : The Enchanting Sea Monsters on Medieval Maps

- Atlas Obscura : For Sale: A 16th-Century Map of Iceland, Roamed by Fantastic Beasts

- GeoGarage blog : Royal Navy 'does not keep sea monster ... / Can you spot all the sea monsters in this ... / Mapping the menacing sea monsters in ... / Crazy-looking new deep-sea creatures / The great challenge of mapping the sea / Beware of the sea monster! Book charts ... / Why ancient mapmakers were terrified of ... / The making of a mysterious Renaissance map

No comments:

Post a Comment