The Prime Meridian line.

Photograph by Danita Delimont, Alamy

Photograph by Danita Delimont, Alamy

From National Geographic

Some 250 years ago, a British astronomer published the first of a series of guidebooks that would ultimately establish Greenwich, England, as the world's zero-degree longitude location, the "prime meridian."

Nevil Maskelyne's 1763 The British Mariner's Guide—and his follow-up The Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris, published annually beginning in 1766—would set the standard for nautical navigation for decades to come.

And though the world has largely forgotten the Guide and Almanac, modern technology has not.

Any device that uses maps and geolocation—from smartphones to global positioning system (GPS) devices to GPS-enabled trucks, airplanes, and ships—still hails the prime meridian flag that Maskelyne planted at his observatory, the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, two-and-a-half centuries ago.

That's because defining zero degrees longitude—which effectively divides the world into East and West—is the first step toward finding every other point of longitude on the map, and finding your way in general.

And that was once a very big deal.

A Longitude Problem

Indeed, before the Guide and Almanac, the world had a deadly longitude problem.

Navigation at sea was extremely difficult, resulting in countless disasters and disappearances over the centuries because ships' captains simply could not figure out where they were.

For instance, on Oct. 22, 1707, more than 1,400 British sailors died because a storm caused the fleet's navigators to lose their location; then the navigators and naval officers mistook the craggy archipelago on which the fleet wrecked for the western entrance to the English Channel.

Pre-Meridian sailing was difficult, as depicted in this illustration of

the Vitus Bering expedition wrecked upon the Aleutian Isles in 1741.

Illustration from North Wind Picture Archive/Alamy

Illustration from North Wind Picture Archive/Alamy

No mere academic exercise, this breakthrough would enable mariners around the world to locate their longitude at sea—turning the moon into the world's first global positioning satellite.

Though he was not the first scientist who attempted to resolve the longitude issue, Maskelyne was the first to put forward a practical solution, one that wound up being so good it effectively enshrined Greenwich as the prime meridian for the entire world, says Rebekah Higgitt, curator of history of science and technology at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich.

Thus he was, she says, "very central to creating Greenwich as it has come to be known.

The discovery of a way to measure longitude revolutionised long-distance sea travel forever, but the institution which made it happen has all but disappeared from memory.

Now researchers led by Professor Simon Schaffer are launching a new project to remember the Board of Longitude and tell its remarkable story in full for the first time.

An Arbitrary Matter

Unlike latitude, which represents angular distance from the equator, longitude on a spinning earth is based on a zero-degree prime meridian that's simply a matter of arbitrary convention.

By the 1760s, many seagoing nations had established their own zero-degree longitude point.

The Royal Observatory in Paris, for example, was France's prime meridian, while the tip of the most southwestern of the Canary Islands was Spain's prime meridian.

Naturally, Great Britain produced maps and charts based on its prime meridian in Greenwich.

But what transformed the country's standard into the worldwide standard was the precision, practicality, and utility of Britain's longitude solution.

For more than two centuries before Maskelyne, scholars across Europe had been talking about using the moon to find longitude at sea.

But two vast problems stood in the way.

The first involved measurement.

No simple, portable device existed to precisely gauge the angular separation between the moon and the sun or a known reference star—the raw numbers navigators needed to derive longitude. But between 1730 and 1760, various technologists across Europe devised ever-better quadrants, octants, and sextants that solved the measurement problem.

Mapping the Moon's Position

The second and larger issue was prediction: In order for a sailor or anyone else to know his longitude, one must compare local time (via a sundial, for instance) with the exact local time at the prime meridian, using some sort of universal clock.

And the best universal timepiece, scientists throughout the 17th and 18th centuries recognized, is the moon, which slowly moves through the sky over a 28-day cycle.

So its position compared with the location of the sun or the stars could serve as the celestial clock's hand.

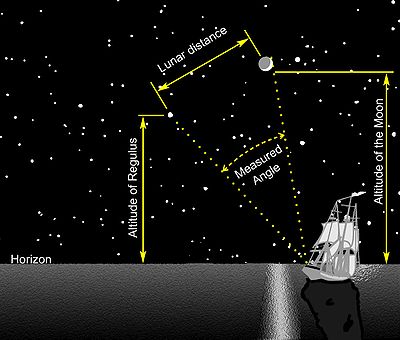

Finding Greenwich time while at sea using a lunar distance.

The Lunar Distance is the angle between the Moon and a star (or the Sun).

The altitudes of the two bodies are used to make corrections and determine the time.

Unfortunately, the moon's precise motion through the sky is anything but regular.

Tugged as it is variously by the earth and sun and following an oblong orbit that never is quite the same, the moon's exact path was extraordinarily difficult to forecast in advance.

That is, until the 1750s, when German mapmaker Tobias Mayer finally mastered the pages of complex equations that would enable astronomers to precisely forecast the moon's position a year or more ahead of time.

This discovery would finally provide navigators with the lunar almanacs they needed.

In the spring of 1763, Maskelyne published the first lunar charts based on Mayer's work in his British Mariner's Guide, allowing navigators to measure the moon's position in the sky and to derive Greenwich time at that very instant.

Ships' captains and navigators could better do their jobs, kicking off a decade of revolutionary innovation that solved one of the greatest technological problems of the 18th century—navigation at sea.

"This method carried into practice," Maskelyne wrote in the Mariner's Guide, "will ... bring the longitude to great nearness."

Still, the British Mariner's Guide left a lot of legwork to be done.

Navigators using the Guide could spend up to four hours calculating their location.

Maskelyne's solution was feasible, in other words, but it was still not practical.

Lunars in the Nautical Almanac (Reed Navigation)

Online tool : A complete online Nautical Almanac covering the period 1750 to 2050.

The positions of the Sun, Moon, navigational planets and stars are generated for every hour of the day at a high level of accuracy just as in the published almanacs;

it permits customization of display options so that data are generated that are relevant for your location and interests.

it permits customization of display options so that data are generated that are relevant for your location and interests.

A Navigational Breakthrough

However, with Maskelyne's subsequent innovation, the Nautical Almanac, it took just 30 minutes to crank out lunar longitudes.

The Almanac anticipated every possible calculation that could be done in advance and simply listed the answers in a reference table, so mariners at sea did not have to run the numbers themselves.

To do this, Maskelyne employed a cottage industry of human "computers"—mathematical prodigies whose only job was to crunch the numbers that would ultimately appear in the Almanac—working day and night beginning in 1765.

Now to find a boat's longitude at sea, all a navigator needed to know was the local time and the position of the moon and a nearby reference point, whether that was the sun or a well-known evening star.

Thus, the Almanac was a breakthrough for mariners, including one of its first customers, Lieutenant (ultimately Captain) James Cook, who field-tested the reference book on his first voyage around the world, finding it superior to any way-finding technique he'd yet seen.

The normally reserved Cook recorded in his journals his pleasure with the Almanac's precision and ease of use.

"It is only by this means that this method of finding the longitude at sea can be brought into universal practice," Cook wrote.

"[It is] a method which we have found may be depended on to within a half a degree! Which is a degree of accuracy more than sufficient for all nautical purposes."

It's Official

Higgitt says that soon after the Almanac—which like the Mariner's Guide before it used the Greenwich Observatory as its prime meridian—was published, merchant fleets and navies beyond British shores began to adopt Britain's superior navigational technology.

For example, France's nautical almanacs, Connaissance des Temps, simply reprinted Maskelyne's lunar charts verbatim from 1772 onward—effectively appointing Greenwich as their prime meridian too.

Moreover, British cartographers used the Mariner's Guide and Almanac to help them map the planet.

This opened up another channel to disseminate the Greenwich prime meridian around the world, as navies and merchant fleets from France, Holland, Spain, and elsewhere came to rely on the often superlative British maps.

By 1884, some 72 percent of the world's shipping tonnage was following the Greenwich standard. And that year, a congress of nations around the world made it official, declaring the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England, as the Earth's true prime meridian.

Time zones

Greenwich Time

After Greenwich was appointed the Earth's geographical standard-bearer, a similar need for a global time standard led it to become the world's default timekeeper too.

So whenever NASA today launches a rocket into outer space, its clocks are set not to Houston or Kennedy Space Center time but rather to absolute Greenwich Time, also called "Universal Time," which doesn't change with the seasons like in other time zones.

Airplane pilots also use Greenwich as their fallback time zone, calling it "Zulu Time."

Moreover, the selection of Greenwich as the prime meridian helped establish the international date line exactly halfway around the globe from Greenwich.

Transpacific travelers must set their calendars ahead by one day when they travel west across the date line, and back by one day when they cross it going east.

And so today, the prime meridian at Greenwich, England, stands as a quiet testimonial on every modern map, navigational chart, and GPS device to the astronomers who finally cracked the longitude puzzle, changing the world—including how easily we get from place to place and tell what time it is when we arrive—forever.

Links :

- GeoGarage blog : Longitude - The story of a lone genius who solved the greatest scientific problem of his time

- St Andrews University : English attack on the Longitude Problem

- CaptainCookSociety : Solving the Problem of Longitude

No comments:

Post a Comment